How Texas Discovered Columbus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States of America Assassination

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ASSASSINATION RECORDS REVIEW BOARD *** PUBLIC HEARING Federal Building 1100 Commerce Room 7A23 Dallas, Texas Friday, November 18, 1994 The above-entitled proceedings commenced, pursuant to notice, at 10:00 a.m., John R. Tunheim, chairman, presiding. PRESENT FOR ASSASSINATION RECORDS REVIEW BOARD: JOHN R. TUNHEIM, Chairman HENRY F. GRAFF, Member KERMIT L. HALL, Member WILLIAM L. JOYCE, Member ANNA K. NELSON, Member DAVID G. MARWELL, Executive Director WITNESSES: JIM MARRS DAVID J. MURRAH ADELE E.U. EDISEN GARY MACK ROBERT VERNON THOMAS WILSON WALLACE MILAM BEVERLY OLIVER MASSEGEE STEVE OSBORN PHILIP TenBRINK JOHN McLAUGHLIN GARY L. AGUILAR HAL VERB THOMAS MEROS LAWRENCE SUTHERLAND JOSEPH BACKES MARTIN SHACKELFORD ROY SCHAEFFER 2 KENNETH SMITH 3 P R O C E E D I N G S [10:05 a.m.] CHAIRMAN TUNHEIM: Good morning everyone, and welcome everyone to this public hearing held today in Dallas by the Assassination Records Review Board. The Review Board is an independent Federal agency that was established by Congress for a very important purpose, to identify and secure all the materials and documentation regarding the assassination of President John Kennedy and its aftermath. The purpose is to provide to the American public a complete record of this national tragedy, a record that is fully accessible to anyone who wishes to go see it. The members of the Review Board, which is a part-time citizen panel, were nominated by President Clinton and confirmed by the United States Senate. I am John Tunheim, Chair of the Board, I am also the Chief Deputy Attorney General from Minnesota. -

Overview of Race and Crime, We Must First Set the Parameters of the Discussion, Which Include Relevant Definitions and the Scope of Our Review

Overview CHAPTER 1 of Race and Crime Because skin color is socially constructed, it can also be reconstructed. Thus, when the descendants of the European immigrants began to move up economically and socially, their skins apparently began to look lighter to the whites who had come to America before them. When enough of these descendants became visibly middle class, their skin was seen as fully white. The biological skin color of the second and third generations had not changed, but it was socially blanched or whitened. —Herbert J. Gans (2005) t a time when the United States is more diverse than ever, with the minority popula- tion topping 100 million (one in every three U.S. residents; U.S. Census Bureau, 2010), the notion of race seems to permeate almost every facet of American life. A Certainly, one of the more highly charged aspects of the race dialogue relates to crime. Before embarking on an overview of race and crime, we must first set the parameters of the discussion, which include relevant definitions and the scope of our review. When speaking of race, it is always important to remind readers of the history of the concept and some current definitions. The idea of race originated 5,000 years ago in India, but it was also prevalent among the Chinese, Egyptians, and Jews (Gossett, 1963). Although François Bernier (1625–1688) is usually credited with first classifying humans into distinct races, Carolus Linnaeus (1707–1778) invented the first system of categorizing plants and humans. It was, however, Johan Frederich Blumenbach (1752–1840) who developed the first taxonomy of race. -

Table of Contents

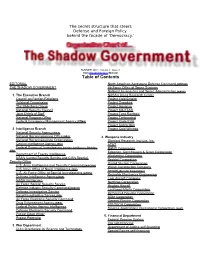

The secret structure that steers Defense and Foreign Policy behind the facade of 'Democracy.' SUMMER 2001 - Volume 1, Issue 3 from TrueDemocracy Website Table of Contents EDITORIAL North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) THE SHADOW GOVERNMENT Air Force Office of Space Systems National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) 1. The Executive Branch NASA's Ames Research Center Council on Foreign Relations Project Cold Empire Trilateral Commission Project Snowbird The Bilderberg Group Project Aquarius National Security Council Project MILSTAR Joint Chiefs of Staff Project Tacit Rainbow National Program Office Project Timberwind Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Project Code EVA Project Cobra Mist 2. Intelligence Branch Project Cold Witness National Security Agency (NSA) National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) 4. Weapons Industry National Reconnaissance Organization Stanford Research Institute, Inc. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) AT&T Federal Bureau of Investigation , Counter Intelligence Division RAND Corporation (FBI) Edgerton, Germhausen & Greer Corporation Department of Energy Intelligence Wackenhut Corporation NSA's Central Security Service and CIA's Special Bechtel Corporation Security Office United Nuclear Corporation U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Walsh Construction Company U.S. Navy Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) Aerojet (Genstar Corporation) U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI) Reynolds Electronics Engineering Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) Lear Aircraft Company NASA Intelligence Northrop Corporation Air Force Special Security Service Hughes Aircraft Defense Industry Security Command (DISCO) Lockheed-Maritn Corporation Defense Investigative Service McDonnell-Douglas Corporation Naval Investigative Service (NIS) BDM Corporation Air Force Electronic Security Command General Electric Corporation Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) PSI-TECH Corporation Federal Police Agency Intelligence Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) Defense Electronic Security Command Project Deep Water 5. -

University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland

UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN EAU CLAIRE CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION Study Abroad UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW, GLASGOW, SCOTLAND 2020 Program Guide ABLE OF ONTENTS Sexual Harassment and “Lad Culture” in the T C UK ...................................................................... 12 Academics .............................................................. 5 Emergency Contacts ...................................... 13 Pre-departure Planning ..................................... 5 911 Equivalent in the UK ............................... 13 Graduate Courses ............................................. 5 Marijuana and other Illegal Drugs ................ 13 Credits and Course Load .................................. 5 Required Documents .......................................... 14 Registration at Glasgow .................................... 5 Visa ................................................................... 14 Class Attendance ............................................... 5 Why Can’t I fly through Ireland? ................... 14 Grades ................................................................. 6 Visas for Travel to Other Countries .............. 14 Glasgow & UWEC Transcripts ......................... 6 Packing Tips ........................................................ 14 UK Academic System ....................................... 6 Weather ............................................................ 14 Semester Students Service-Learning ............. 9 Clothing............................................................ -

Sipanews Winter 2000 / VOLUME Xiii NO.1 1 from the Dean Lisa Anderson Takes Stock of SIPA in the New Millenium

SIPAnews winter 2000 / VOLUME XIiI NO.1 1 From the Dean Lisa Anderson takes stock of SIPA in the new millenium. 2 Economist Robert Mundell is Columbias latest Nobel Prize winner. 3 Professor Kathleen Molz takes a critical look at Internet filters. 4 Dear SIPA 99 grad Jun Choi tells us about life on the campaign trail. 5 Alumni Profile: John Neuffer Cold pizza leads to 15 minutes of fame for SIPA grad. 6 Alumni Forum: Cecelia Caruso Alumna fights for textbooks for New York children of color. 8 Executive MPA Program makes SIPA debut. 7 Schoolwide News 10 13 MPA Program News Six SIPA students bring love and laughter to Kosovo refugees. 14 MIA Program News 15 Urban Affairs 12 17 Faculty News SIPA student groups offer something for everyone. 20 Staff News 21 Class Notes SIPA news 1 Our more recent alumni- should we call you the ele- vator classes?-continue to remember the faculty as having a profound impact on their lives and careers. From the Dean: Lisa Anderson Raise a Glass to SIPA As Clock Strikes Midnight ebrate them. We and the economics energy and other resources to conduct department bask in the reflected glory their own research and policy analysis. of Professor Robert Mundells Nobel We at SIPA have enjoyed and profited Prize, of course, but also enjoy the from their dedication to teaching and honors and awards a number of other to strengthening our institution, and at faculty are collecting, including long last we are in a position to recip- Robert Liebermans Trilling Prize for rocate what they have done for us. -

A History of Appalachia

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Appalachian Studies Arts and Humanities 2-28-2001 A History of Appalachia Richard B. Drake Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Drake, Richard B., "A History of Appalachia" (2001). Appalachian Studies. 23. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_appalachian_studies/23 R IC H ARD B . D RA K E A History of Appalachia A of History Appalachia RICHARD B. DRAKE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by grants from the E.O. Robinson Mountain Fund and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2001 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2003 Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kenhlcky Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 12 11 10 09 08 8 7 6 5 4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Drake, Richard B., 1925- A history of Appalachia / Richard B. -

Books Added to Benner Library from Estate of Dr. William Foote

Books added to Benner Library from estate of Dr. William Foote # CALL NUMBER TITLE Scribes and scholars : a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature / by L.D. Reynolds and N.G. 1 001.2 R335s, 1991 Wilson. 2 001.2 Se15e Emerson on the scholar / Merton M. Sealts, Jr. 3 001.3 R921f Future without a past : the humanities in a technological society / John Paul Russo. 4 001.30711 G163a Academic instincts / Marjorie Garber. Book of the book : some works & projections about the book & writing / edited by Jerome Rothenberg and 5 002 B644r Steven Clay. 6 002 OL5s Smithsonian book of books / Michael Olmert. 7 002 T361g Great books and book collectors / Alan G. Thomas. 8 002.075 B29g Gentle madness : bibliophiles, bibliomanes, and the eternal passion for books / Nicholas A. Basbanes. 9 002.09 B29p Patience & fortitude : a roving chronicle of book people, book places, and book culture / Nicholas A. Basbanes. Books of the brave : being an account of books and of men in the Spanish Conquest and settlement of the 10 002.098 L552b sixteenth-century New World / Irving A. Leonard ; with a new introduction by Rolena Adorno. 11 020.973 R824f Foundations of library and information science / Richard E. Rubin. 12 021.009 J631h, 1976 History of libraries in the Western World / by Elmer D. Johnson and Michael H. Harris. 13 025.2832 B175d Double fold : libraries and the assault on paper / Nicholson Baker. London booksellers and American customers : transatlantic literary community and the Charleston Library 14 027.2 R196L Society, 1748-1811 / James Raven. -

Good Chemistry James J

Columbia College Fall 2012 TODAY Good Chemistry James J. Valentini Transitions from Longtime Professor to Dean of the College your Contents columbia connection. COVER STORY FEATURES The perfect midtown location: 40 The Home • Network with Columbia alumni Front • Attend exciting events and programs Ai-jen Poo ’96 gives domes- • Dine with a client tic workers a voice. • Conduct business meetings BY NATHALIE ALONSO ’08 • Take advantage of overnight rooms and so much more. 28 Stand and Deliver Joel Klein ’67’s extraordi- nary career as an attorney, educator and reformer. BY CHRIS BURRELL 18 Good Chemistry James J. Valentini transitions from longtime professor of chemistry to Dean of the College. Meet him in this Q&A with CCT Editor Alex Sachare ’71. 34 The Open Mind of Richard Heffner ’46 APPLY FOR The venerable PBS host MEMBERSHIP TODAY! provides a forum for guests 15 WEST 43 STREET to examine, question and NEW YORK, NY 10036 disagree. TEL: 212.719.0380 BY THOMAS VIncIGUERRA ’85, in residence at The Princeton Club ’86J, ’90 GSAS of New York www.columbiaclub.org COVER: LESLIE JEAN-BART ’76, ’77J; BACK COVER: COLIN SULLIVAN ’11 WITHIN THE FAMILY DEPARTMENTS ALUMNI NEWS Déjà Vu All Over Again or 49 Message from the CCAA President The Start of Something New? Kyra Tirana Barry ’87 on the successful inaugural summer of alumni- ete Mangurian is the 10th head football coach since there, the methods to achieve that goal. The goal will happen if sponsored internships. I came to Columbia as a freshman in 1967. (Yes, we you do the other things along the way.” were “freshmen” then, not “first-years,” and we even Still, there’s no substitute for the goal, what Mangurian calls 50 Bookshelf wore beanies during Orientation — but that’s a story the “W word.” for another time.) Since then, Columbia has compiled “The bottom line is winning,” he said. -

Glen Ridge High School 1 Page Oct 20, 2020 at 11:39 Am Weeding List

GLEN - Glen Ridge High School Oct 20, 2020 at 11:39 am 1Page Weeding List (164) by Copy Call Number Alexandria 6.23.1 Selected:All Copies Call # Title Year Barcode LTD Use Last Use Bloom's guide to Khaled Hosseini's The kite ru... 2009 57820000588429 0 None Chromebook charger NONE 57820000297351 3 03/09/2020 Medicine, health, and bioethics : essential prim... 2006 57820000538013 0 None NO TITLE NONE EEUFET8I 0 None NO TITLE NONE ETU 0 None NO TITLE NONE AUCIEZEU 0 None NO TITLE NONE ENA1GCAL 0 None NO TITLE NONE OIAIQA8CNH5 0 None NO TITLE NONE UAADCEGLZU 0 None NO TITLE NONE EVECA 0 None NO TITLE NONE ZEIOHUAAA 0 None NO TITLE NONE CUOCEZMPE 0 None NO TITLE NONE KEAOUADNA 0 None NO TITLE NONE ED8ERHZU 0 None NO TITLE NONE ESEU 0 None NO TITLE NONE RAIQGCCOAU 0 None NO TITLE NONE AEZJEHSSSPU 0 None NO TITLE NONE CPNARECOE 0 None NO TITLE NONE SON 0 None NO TITLE NONE EEHBVNEUERZO 0 None NO TITLE NONE ENODBOAII 0 None NO TITLE NONE IHBDIIH 0 None NO TITLE NONE HTVUQZUKEEE 0 None NO TITLE NONE BBACCNZNU 0 None NO TITLE NONE 1301309 0 None Famous military trials 1980 57820000517881 0 None Geis 2016 5782000058211 0 None A Christmas carol 2008 57820000587959 0 None Recipes from the Chateaux of the Loire 1998 57820000169873 0 None The burning bridge 2005 57820000520174 7 12/07/2015 Winning in the game of life : self-coaching secr... 1999 57820000157423 0 None The scarlet letter 2006 57820000587991 0 None 20s & '30s style 1989 57820000079437 2 01/31/2013 The kite runner 2008 57820000585433 0 None The Hudson River and its painters 1983 57820000283815 0 None Literary criticism - French writers, other Europea...1984 57820000080427 0 None Napoleon's glands : and other ventures in bioh.. -

PEGODA-DISSERTATION-2016.Pdf (3.234Mb)

© Copyright by Andrew Joseph Pegoda December, 2016 “IF YOU DO NOT LIKE THE PAST, CHANGE IT”: THE REEL CIVIL RIGHTS REVOLUTION, HISTORICAL MEMORY, AND THE MAKING OF UTOPIAN PASTS _______________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Andrew Joseph Pegoda December, 2016 “IF YOU DO NOT LIKE THE PAST, CHANGE IT”: THE REEL CIVIL RIGHTS REVOLUTION, HISTORICAL MEMORY, AND THE MAKING OF UTOPIAN PASTS ____________________________ Andrew Joseph Pegoda APPROVED: ____________________________ Linda Reed, Ph.D. Committee Chair ____________________________ Nancy Beck Young, Ph.D. ____________________________ Richard Mizelle, Ph.D. ____________________________ Barbara Hales, Ph.D. University of Houston-Clear Lake ____________________________ Steven G. Craig, Ph.D. Interim Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Department of Economics ii “IF YOU DO NOT LIKE THE PAST, CHANGE IT”: THE REEL CIVIL RIGHTS REVOLUTION, HISTORICAL MEMORY, AND THE MAKING OF UTOPIAN PASTS _______________ An Abstract of A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Andrew Joseph Pegoda December, 2016 ABSTRACT Historians have continued to expand the available literature on the Civil Rights Revolution, an unprecedented social movement during the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s that aimed to codify basic human and civil rights for individuals racialized as Black, by further developing its cast of characters, challenging its geographical and temporal boundaries, and by comparing it to other social movements both inside and outside of the United States. -

Current Strategic Business Plan for the Implementation of Digital

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 482 968 EC 309 831 Current Strategic Business Plan for the Implementation of TITLE Digital Systems. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, DC. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. PUB DATE 2003-12-00 NOTE 245p. AVAILABLE FROM Reference Section, National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, Washington, DC 20542. For full text: http://www.loc.gov.html. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Computer System Design; Library Networks ABSTRACT This document presents a current strategic business plan for the implementation of digital systems and servicesfor the free national library program operated by the National LibraryService for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, its networkof cooperating regional and local libraries, and the United StatesPostal Service. The program was established in 1931 and isfunded annually by Congress. The plan will be updated and refined as supporting futurestudies are completed. (AMT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ., . I a I a a a p , :71110i1 aafrtexpreve ..4111 AAP"- .4.011111rAPrip -"" Al MI 1111 U DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Oth of Educattonal Research and Improvement ED ATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION .a.1111PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND CENTER (ERIC) DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS IN" This document has been reproduced as BEEN GRANTED BY received from the person -

Multi-Periodic Pulsations of a Stripped Red Giant Star in an Eclipsing Binary

1 Multi-periodic pulsations of a stripped red giant star in an eclipsing binary Pierre F. L. Maxted1, Aldo M. Serenelli2, Andrea Miglio3, Thomas R. Marsh4, Ulrich Heber5, Vikram S. Dhillon6, Stuart Littlefair6, Chris Copperwheat7, Barry Smalley1, Elmé Breedt4, Veronika Schaffenroth5,8 1 Astrophysics Group, Keele University, Keele, Staffordshire, ST5 5BG, UK. 2 Instituto de Ciencias del Espacio (CSIC-IEEC), Facultad de Ciencias, Campus UAB, 08193, Bellaterra, Spain. 3 School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TT, UK. 4 Department of Physics, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK. 5 Dr. Karl Remeis-Observatory & ECAP, Astronomical Institute, Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg, Sternwartstr. 7, 96049, Bamberg, Germany. 6 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, S3 7RH, UK. 7Astrophysics Research Institute, Liverpool John Moores University, Twelve Quays House, Egerton Wharf, Birkenhead, Wirral, CH41 1LD, UK. 8Institute for Astro- and Particle Physics, University of Innsbruck, Technikerstrasse. 25/8, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria. Low mass white dwarfs are the remnants of disrupted red giant stars in binary millisecond pulsars1 and other exotic binary star systems2–4. Some low mass white dwarfs cool rapidly, while others stay bright for millions of years due to stable 2 fusion in thick surface hydrogen layers5. This dichotomy is not well understood so their potential use as independent clocks to test the spin-down ages of pulsars6,7 or as probes of the extreme environments in which low mass white dwarfs form8–10 cannot be fully exploited. Here we present precise mass and radius measurements for the precursor to a low mass white dwarf.