Compendium: Electronic Recording of Custodial Interrogations INDEX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preemptive Narratives in Recent Television Series Par Toni Pape

Université de Montréal Figures of Time: Preemptive Narratives in Recent Television Series par Toni Pape Département de littérature comparée, Faculté des arts et des sciences Thèse présentée à la Faculté des arts et des sciences en vue de l’obtention du grade de Ph. D. en Littérature, option Études littéraires et intermédiales Juillet 2013 © Toni Pape, 2013 Résumé Cette thèse de doctorat propose une analyse des temporalités narratives dans les séries télévisées récentes Life on Mars (BBC, 2006-2007), Flashforward (ABC, 2009-2010) et Damages (FX/Audience Network, 2007-2012). L’argument général part de la supposition que les nouvelles technologies télévisuelles ont rendu possible de nouveaux standards esthétiques ainsi que des expériences temporelles originales. Il sera montré par la suite que ces nouvelles qualités esthétiques et expérientielles de la fiction télévisuelle relèvent d’une nouvelle pertinence politique et éthique du temps. Cet argument sera déployé en quatre étapes. La thèse se penche d’abord sur ce que j’appelle les technics de la télévision, c’est-à- dire le complexe de technologies et de techniques, afin d’élaborer comment cet ensemble a pu activer de nouveaux modes d’expérimenter la télévision. Suivant la philosophie de Gilles Deleuze et de Félix Guattari ainsi que les théories des médias de Matthew Fuller, Thomas Lamarre et Jussi Parikka, ce complexe sera conçu comme une machine abstraite que j’appelle la machine sérielle. Ensuite, l’argument puise dans des théories de la perception et des approches non figuratives de l’art afin de mieux cerner les nouvelles qualités d’expérience esthétique dans la fiction sérielle télévisée. -

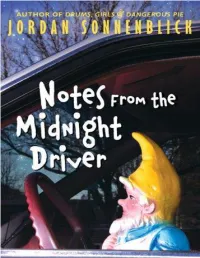

Notes from the Midnight Driver

Notes From the Midnight Driver Jordan Sonnenblick SCHOLASTIC INC. New York Toronto London Auckland Sydney Mexico City New Delhi Hong Kong Buenos Aires To my grandfather, Solomon Feldman, who inspired this book, and to the memory of my father, Dr. Harvey Sonnenblick, who loved it Table of Contents Title Page Dedication May Last September Gnome Run The Wake-Up Day Of The Dork-Wit My Day In Court Solomon Plan B Laurie Meets Sol Sol Gets Interested Half An Answer Happy Holidays The Ball Falls Happy New Year! Enter The Cha-Kings Home Again Am I A Great Musician, Or What? A Night For Surprises Darkness The Valentine’s Day Massacre Good Morning, World! The Mission The Saints Go Marchin’ In The Work Of Breathing Peace In My Tribe Finale Coda The Saints Go Marchin’ In Again Thank you Notes About the Author Interview Sneak Peek Copyright May Boop. Boop. Boop. I’m sitting next to the old man’s bed, watching the bright green line spike and jiggle across the screen of his heart monitor. Just a couple of days ago, those little mountains on the monitor were floating from left to right in perfect order, but now they’re jangling and jerking like maddened hand puppets. I know that sometime soon, the boops will become one long beep, the mountains will crumble into a flat line, and I will be finished with my work here. I will be free. LAST SEPTEMBER GNOME RUN It seemed like a good idea at the time. Yes, I know everybody says that—but I’m serious. -

Intersection of Gender and Italian/Americaness

THE INTERSECTION OF GENDER AND ITALIAN/AMERICANESS: HEGEMONY IN THE SOPRANOS by Niki Caputo Wilson A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL December 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I could not have completed this dissertation without the guidance of my committee members, the help from my friends and colleagues, and the support of my family. I extend my deepest gratitude to my committee chair Dr. Jane Caputi for her patience, guidance, and encouragement. You are truly an inspiration. I would like to thank my committee members as well. Dr. Christine Scodari has been tireless in her willingness to read and comment on my writing, each time providing me with insightful recommendations. I am indebted to Dr Art Evans, whose vast knowledge of both The Sopranos and ethnicity provided an invaluable resource. Friends, family members, and UCEW staff have provided much needed motivation, as well as critiques of my work; in particular, I thank Marc Fedderman, Rebecca Kuhn, my Aunt Nancy Mitchell, and my mom, Janie Caputo. I want to thank my dad, Randy Caputo, and brother, Sean Caputo, who are always there to offer their help and support. My tennis friends Kathy Fernandes, Lise Orr, Rachel Kuncman, and Nicola Snoep were instrumental in giving me an escape from my writing. Mike Orr of Minuteman Press and Stefanie Gapinski of WriteRight helped me immensely—thank you! Above all, I thank my husband, Mike Wilson, and my children, Madi and Cole Wilson, who have provided me with unconditional love and support throughout this process. -

Merchants of Discontent: an Exploration of the Psychology of Advertising, Addiction and Its Implications for Commercial Speech Tamara Piety

University of Tulsa College of Law TU Law Digital Commons Articles, Chapters in Books and Other Contributions to Scholarly Works 2002 Merchants of Discontent: An Exploration of the Psychology of Advertising, Addiction and Its Implications for Commercial Speech Tamara Piety Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/fac_pub Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation 25 Seattle .U L. Rev. 377 (2001). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles, Chapters in Books and Other Contributions to Scholarly Works by an authorized administrator of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Merchants of Discontent":t An Exploration of the Psychology of Advertising, Addiction, and the Implications for Commercial Speech Tamara R. Piety* A really efficient totalitarian state would be one in which the all-powerful executive of political bosses and their army of managers control a population of slaves who do not have to be coerced, because they love their servitude.' TABLE OF CONTENTS IN TRODUCTION ........................................................ 379 I. OVERVIEW OF COMMERCIAL SPEECH DOCTRINE .....382 A . W here's the H arm ? .............................................. 382 B. The Development of Commercial Speech D octrine ............................................................. 388 C. "Puffing": Advertising Manipulation as Trivial and Inconsequential .................................................... 394 II. THE FIRST AMENDMENT, AUTONOMY, RATIONALITY, AND PATERNALISM ............................396 A. Visions of Autonomy ........................................... 398 B. Autonomy and Rationality: The Importance of Be- ing R ational ......................................................... 400 t VANCE PACKARD, THE HIDDEN PERSUADERS 22 (1957). Packard noted, "An ad executive from Milwaukee related in Printer'sInk that America was growing great by the systematic creation of dissatisfaction." Id. -

Media Approved

Film and Video Labelling Body Media Approved Video Titles Title Rating Source Time Date Format Applicant Point of Sales Approved Director Cuts 12 Rounds 2: Reloaded M Violence,offensive language and sex scenes FVLB 95.00 12/09/2013 Film - Online Vodafone Fixed Roel Reine No cut noted 12-12-12 The Concert For Sandy Relief PG Adult themes FVLB 156.04 20/09/2013 DVD Sony Music NZ Michael Dempsey No cut noted Slick Yes 20/09/2013 14-18 The Noise and the Fury M Content may disturb FVLB 100.00 04/09/2013 DVD The Warehouse Jean-Francois Delassus No cut noted Slick Yes 04/09/2013 2 Broke Girls The Complete Second Season M Drug references and sexual references FVLB 507.18 02/09/2013 DVD Warner Bros Video Various No cut noted Slick Yes 02/09/2013 5 Day Fit: Abs G FVLB 108.00 16/09/2013 DVD The Warehouse N/A No cut noted Slick Yes 16/09/2013 A To Zeppelin The Unauthorized Story Of Led Zeppelin M Low level offensive language FVLB 55.00 04/09/2013 DVD The Warehouse Dante Pugliese (Executive No cut noted Slick Yes 04/09/2013 Aap Ki Khatir / Kabhi Alvida Na Kehna M Sexual references FVLB 318.00 26/09/2013 DVD Shree Rhythm Video Dharmesh Darshan/Karan No cut noted ABBA - Ring Ring G FVLB 14.08 25/09/2013 DVD Universal Music Unknown No cut noted Slick Yes 25/09/2013 Ace Ventura-Pet Detective PG Coarse language FVLB 86.00 25/09/2013 Bluray Warner Bros Video Tom Shadyac No cut noted Slick Yes 25/09/2013 Ace Ventura-When Nature Calls PG Sexual references FVLB 94.03 25/09/2013 Bluray Warner Bros Video Steve Oedekerk No cut noted Slick Yes 25/09/2013 Adaptation -

Alaska Youth Law Guide: a Handbook for Teens and Young Adults

Alaska Youth Law Guide: A Handbook for Teens and Young Adults This publication is a public education resource presented by the Alaska Bar Association Law-Related Education Committee to help young Alaskans understand the law and how it may affect them. You will find general information about many of the legal issues teens and young adults are likely to encounter, and some resources for getting more information or assistance. We hope you find it helpful! Please note that this is a PDF copy of the live version current as of June 2017. The PDF version is published once a year. If you need more updated information, please check the website. Important Information about Using the Alaska Youth Law Guide This guide is not a substitute for having a lawyer. It does not provide specific legal advice and you cannot rely on the information presented here to solve a legal problem for you. Every legal problem is different, and there may be something about your situation that makes the general information presented here not applicable to you. There is no attorney-client relationship between you and the staff of the Alaska Bar Association or the Law-Related Education Committee. You are strongly encouraged to seek the services of an attorney for legal advice and strategy. The information presented here was accurate to the best of the Committee’s knowledge at the time it was posted. However, laws change frequently. Therefore, some of the information you read may be inaccurate or incomplete based on changes in the law since the Guide was written. -

This American Copyright Life 201 THIS AMERICAN COPYRIGHT LIFE: REFLECTIONS on RE-EQUILIBRATING COPYRIGHT for the INTERNET AGE

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 1 1-MAY-14 10:19 This American Copyright Life 201 THIS AMERICAN COPYRIGHT LIFE: REFLECTIONS ON RE-EQUILIBRATING COPYRIGHT FOR THE INTERNET AGE by PETER S. MENELL* ABSTRACT This article calls attention to the dismal state of copyright’s public approval rating. Drawing on the format and style of Ira Glass’s “This American Life” radio broadcast, the presentation unfolds in three parts: Act I – How did we get here?; Act II – Why should society care about copyright’s public approval rating?; and Act III – How do we improve copyright’s public approval rating (and efficacy)? *Koret Professor of Law, University of California at Berkeley School of Law and co-founder and Director, Berkeley Center for Law & Technology. I owe special thanks to David Anderman, Mark Avsec, Robby Beyers, Jamie Boyle, Hon. Ste- phen G. Breyer, Andrew Bridges, Elliot Cahn, David Carson, Jay Cooper, Jeff Cunard, Victoria Espinel, David Given, Jane Ginsburg, Paul Goldstein, Jim Grif- fin, Dylan Hadfield-Menell, Noah Hadfield-Menell, Scotty Iseri, Dennis Karjala, Rob Kasunic, Chris Kendrick, Mark Lemley, Larry Lessig, Jessica Litman, Rob Merges, Eli Miller, Neal Netanel, Hon. Jon O. Newman, Wood Newton, David Nimmer, Maria Pallante, Shira Perlmutter, Marybeth Peters, Gene Roddenberry, Pam Samuelson, Ellen Seidler, Lon Sobel, Chris Sprigman, Madhavi Sunder, Gary Stiffelman, Pete Townshend, Molly Van Houweling, Fred von Lohmann, Joel Waldfogel, Jeremy Williams, Jonathan Zittrain, and the participants on the Cyber- prof and Pho listserves for inspiration, perspective, provocation, and insight; and Claire Sylvia for her steadfast love, encouragement, and support. -

July 2019 New York State Bar Examination MEE & MPT Questions

July 2019 New York State Bar Examination MEE & MPT Questions © 2019 National Conference of Bar Examiners MEE QUESTION 1 Testator’s handwritten and signed will provided, in its entirety, I am extremely afraid of flying, but I have to fly to City for an urgent engagement. Given that I might die on the trip to City, I write to convey my wish that my entire estate be distributed, in equal shares, to my son John and his delightful wife of many years if anything should happen to me. January 4, 2010 Testator When Testator wrote the will, he was domiciled in State A, and his son John was married to Martha, whom he had married in 2003. Testator had known Martha and her parents for many years, and Testator had introduced Martha to John. At the time John and Martha married, Martha was a widow with two children, ages five and six. Following their wedding, John and Martha raised Martha’s children together, although John never adopted them. Two years ago, Martha was killed in an automobile accident. Six months ago, John married Nancy. Four months ago, Testator died while domiciled in State B. All of his assets were in State B. The handwritten will of January 4, 2010, was found in Testator’s bedside table. Testator was survived by his sons, John and Robert, and John’s wife Nancy. Testator was also survived by Martha’s two children, who have continued to live in John’s home since Martha’s death. State A does not recognize holographic wills. State B, on the other hand, recognizes “wills in a testator’s handwriting so long as the will is dated and subscribed by the testator.” Statutes in both State A and State B provide that “if a beneficiary under a will predeceases the testator, the deceased beneficiary’s surviving issue take the share the deceased beneficiary would have taken unless the will expressly provides otherwise.” How should Testator’s estate be distributed? Explain. -

Keeping It Real: a Historical Look at Reality TV

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2011 Keeping It Real: A Historical Look at Reality TV Jessica Roberts West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Roberts, Jessica, "Keeping It Real: A Historical Look at Reality TV" (2011). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 3438. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/3438 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Keeping It Real: A Historical Look at Reality TV Jessica Roberts Thesis submitted to the P.I. Reed School of Journalism at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Journalism Sara Magee, Ph.D., Chair Steve Urbanski, Ph.D. George Esper, Ph.D. Krystal Frazier, Ph.D. School of Journalism Morgantown, West Virginia 2011 Keywords: reality TV, challenge, talent, makeover, celebrity, product placement Copyright 2011 Jessica Roberts ABSTRACT Keeping It Real: A Historical Look at Reality TV Jessica Roberts In the summer of 2000 CBS launched a wilderness and competition reality show called “Survivor.” The show became a monster hit with more than fifty million viewers watching the finale, ratings only second to Super Bowl. -

Smoke and Mirrors Season 5, Episode 7

PAIGE CARTER Deputy Sheriff Smoke and Mirrors Season 5, Episode 7 by: Melanie P. Smith MPSmith Publishing Copyright © 2020 Melanie P. Smith First Edition | Series: Paige Carter Edited by LaPriel Dye * * * No part of this document or the related files may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any means (electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the Author. www.melaniepsmith.com This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental. All trademarks are the property of their owners and are acknowledged by the proper use of capitalization throughout. MPSmith Publishing Smoke and Mirrors Paige absently reached for the ringing phone as she skimmed through the report she’d just written. “Deputy Carter.” “Paige Carter,” a male voice greeted. “It’s been a while. Calvin Wright here. How are you?” “Wow,” Paige grinned and settled back in her chair. “That’s a blast from the past. I’m great and you?” “Can’t complain,” Calvin told her. “You still giving orders in the freezing metropolis of Green Bay?” “Actually,” Calvin hesitated. “No. That’s actually the reason for my call. My wife’s father passed away nearly ten years ago. Her mom was still pretty self-sufficient — until recently. She fell last year, broke her hip. It took a couple hours before a neighbor found her and called for help. I decided it was time to retire and move to Des Moines. -

Obscenity Charge Nixed on Free Speech Grounds

A4 + PLUS >> Top-five teacher, Opinion/4A LOCAL CHS FOOTBALL Operation Purple & Gold Round Up game tonight See Page 2A See Page 1B WEEKEND EDITION FRIDAY & SATURDAY, MAY 10 & 11, 2019 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $1.00 Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM LAWSUIT PENDING Arrest video Obscenity charge nixed busts on free speech grounds social Saturday Craft beer, wine fest First Amendment media The fourth annual prevails in debate Gateway City Craft Beer over vulgar decal. myths and Wine Festival takes place Saturday, from 2–6 p.m. on the west side of By CARL MCKINNEY By CARL MCKINNEY Lake DeSoto at the inter- [email protected] [email protected] sections of Lake DeSoto Circle and Veterans Street. Prosecutors have The arrest of a Lake Non-alcoholic beverages, declined to file charges City man over a raunchy food, games and live enter- against the 23-year-old bumper stick- tainment will also be on Lake City man arrested Dillon er sparked offer. Advanced tickets are for refusing to remove Webb widespread $25 and $30 on the day of a letter wasn’t social media the event. VIP tickets are from his loud, rude attention, $50, which will provide “I EAT or abusive mostly ridi- 1 p.m. entry, a $10 food ASS” to deputy. cule directed truck voucher and two “full window toward the pour” drink tickets and hors decal, Columbia County Sheriff’s d’oeuvres. For ticket infor- which a COURTESY CCSO Office. mation call 386-752-3690. Webb deputy Dillon Shane Webb, 23, Lake City, is arrested Sunday on an obscenity charge But many have specu- alleged for refusing to remove the decal on the back window of his pickup. -

Rest in Pieces

Rest in Pieces Death on an Undying Medium As Seen on TV’s Dexter, Nip/Tuck, Battlestar Galactica, & Damages A Television Studies Senior Thesis By Leah Longoria Submitted to the Department of Film & Media Studies of Amherst College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with honors with advising by Amelie Hastie April 11, 2012 1 For my two obsessions; television and my twin. 2 Contents / Episode Guide Acknowledgements 4 Teaser: Next, on Rest in Pieces 5 Episode 1: The Body In Pieces: Dexter’s “Ice Truck Killer” 13 Episode 2: The Body Under the Knife: Nip/Tuck’s “Perfect Lie” 35 Episode 3: The Body Resurrected: Battlestar Galactica’s Cylon 64 Episode 4: The Reticulated Body: Damages and the Allure of the Abject Archive of Television 91 Finale: “Fort” and “Da” 108 Bibliography, Television & Filmography 111 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank those who have generously taken time to read portions of this thesis. Most especially, Professor Amelie Hastie, who not only has been an invaluable intellectual resource, but who opened up the world of television to me. What was once, and still is, a favorite pastime has become, too, a form to which I devote scholarly attention. I also want to acknowledge my indebtedness to my parents, Monica Gonzalez and Raul Longoria, whose advice, guidance, and support has been and will continue to be held in high esteem. And finally, though words could never express the regard I have for her; I want to thank Caris Longoria, whose joy and humor inspire me every day.