Neoliberalism and Working- Class Representation in Contemporary Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Informação À Imprensa – XX De Abril De 2008

Títulos disponíveis em Star no Disney+, em Portugal, no dia 23 de fevereiro Séries de televisão 24: LIVE ANOTHER DAY 9/11 FIREHOUSE ACCORDING TO JIM (YR 1 2001/02 EPS 1-22) ACCORDING TO JIM (YR 2 2002/03 EPS 23-50) ACCORDING TO JIM (YR 3 2003/04 EPS 51-79) ACCORDING TO JIM (YR 4 2004/05 EPS 80-106) ACCORDING TO JIM (YR 5 2005/06 EPS 107-128) ACCORDING TO JIM (YR 6 2006/07 EPS 129-146) ACCORDING TO JIM (YR 7 2007/08 EPS 147-164) ACCORDING TO JIM (YR 8 2008/09 EPS 165-182) ALIAS (YR 1 2001/02 EPS 1-22) ALIAS (YR 2 2002/03 EPS 23-44) ALIAS (YR 3 2003/04 EPS 45-66) ALIAS (YR 4 2004/05 EPS 67-88) ALIAS (YR 5 2005/06 EPS 89-105) BIG SKY (YR 1 2020/21 EPS 1-18) BLACKISH (YR 1 2014/15 EPS 1-24) BLACKISH (YR 2 2015/16 EPS 25-48) BLACKISH (YR 3 2016/17 EPS 49-72) BLACKISH (YR 4 2017/18 EPS 73-95) BLACKISH (YR 5 2018/19 EPS 96-118) BROTHERS & SISTERS (YR 1 2006/07 EPS 1-23) BROTHERS & SISTERS (YR 2 2007/08 EPS 24-39) BROTHERS & SISTERS (YR 3 2008/09 EPS 40-63) BROTHERS & SISTERS (YR 4 2009/10 EPS 64-87) BROTHERS & SISTERS (YR 5 2010/11 EPS 88-109) BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER (YR 1 1996/97 EPS 1-12) BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER (YR 2 1997/98 EPS 13-34) BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER (YR 3 1998/99 EPS 35-55) BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER (YR 4 1999/00 EPS 56-78) BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER (YR 5 2000/01 EPS 79-100) BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER (YR 6 2001/02 EPS 101-122) BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER (YR 7 2002/03 EPS 123-144) CASTLE (YR 1 2008/09 EPS 1-10) CASTLE (YR 2 2009/10 EPS 11-34) CASTLE (YR 3 2010/11 EPS 35-58) CASTLE (YR 4 2011/12 EPS 59-81) CASTLE (YR 5 2012/13 EPS 82-105) -

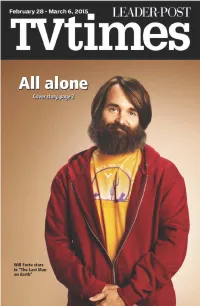

One and Only

Cover Story One and only Fox tackles the loneliest number in ‘The Last Man on Earth’ By Cassie Dresch people after a virus takes out him get into a lot of really silly TV Media all of Earth’s population. His shenanigans. family is gone, his coworkers “It’s all just kind of stupid ello? Hi? Anybody out are gone, the president is gone. stuff that I go around and do,” Hthere? Of course there is, Everyone. Gone. he said in an interview with otherwise life would be very, So what does he do? He “Entertainment Weekly.” very, very lonely. Fox is taking a travels the United States doing “That’s been one of the most stab at the ultimate life of lone- things he never would have fun parts of the job. About once liness in the new half-hour been able to do otherwise — a week I get to do something comedy “The Last Man on sing the national anthem at that seems like it’d be amaz- Earth,” premiering Sunday, Dodger Stadium, smear gooey ingly fun to do: shoot a flame March 1. peanut butter all over a price- thrower at a bunch of wigs, The premise around “Last less piece of art ... then walk have a steamroller steamroll Man” is a simple one, albeit a away with it, break things. The over a case of beer. Just dumb little strange. An average, un- show, according to creator and stuff like that, which pretty assuming man is on the hunt star Will Forte (“Saturday Night much is all it takes to make me for any signs of other living Live,” “Nebraska,” 2013), sees happy.” Registration $25.00 online: www.skseniorsmechanism.ca or phone 306-359-9956 2 Cover Story Flame throwers and steam- ally proud of what has come rollers? Again, it’s a strange out of it so far.” concept, but Fox is really be- Of course, you have to won- Index hind the show. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Angela Meryl

Angela Meryl Gender: Female Service: 818-774-3889 Height: 5 ft. 7 in. Mobile: 201.838.3726 Weight: 124 pounds Web Site: http://angela-meryl.... Eyes: Brown Hair Length: Shoulder Length Waist: 26 Inseam: no info Shoe Size: 7.5 Physique: Athletic Coat/Dress Size: 4 Ethnicity: African American / Black Photos Generated on 09/25/2021 06:53:49 pm Page 1 of 6 Film Credits Think Like A Man 2 Patron # 1/Utility Stunt Larnel Stoval Paranoia Utility Stunts Steve Pope Sky Fall Utility Stunts Gary Powell BATTLESHIP Stnt Dbl. Rihanna Kevin Scott Spores Stunt dbl Joey Box S.W.A.T Fire Fight Stunt dbl/ Shannon Kane Mike Smith Takers Utility Stunts Lance Gilbert Priest Priestess/Stunt Lance Gilbert Premium Rush Utility Stunts Steve Pope Obsessed Stunt dbl/ Beyonce Lance Gilbert The Soloist Homeless Woman/Stunt George Marshall Ruge Pistol Whipped Stunt dbl/ Renee E.Goldsberry Mike Smith Meet Dave Cop/Stunt Andy Gill This Christmas Stunt dbl/ Sharon Neal Merrit Yohnka Pirates of The Caribbean "At Stunt dbl/ Naomi Harris Gore Verbinski/George Marshall Worlds End" Ruge American Gangster Utility Stunts George Aguilar Miami Vice Stunt dbl/ Naomi Harris Michael Mann/Artie Malesci Alpha Dog Party Girl/Stunt Nick Cassavettes/Kerry Rossall Freedomland Utility Stunts J.C. Schroder/George Aguilar Elizabethtown Utility Stunts Cameron Crowe/Doug Crosby Cursed Stunt dbl/ Mya Wes Craven/Charlie Croughwell Collateral Utility Stunts Michael Mann/Joel Kramer The Forgotten Utility Stunts Terry Leonard NY Minute Utility Stunts ConradPalmisano/Mellisa Stubbs/Doug Crosby Havoc Dinah/Stunt Barbara Kopple/Lou Simon Johnson Family Vacation Stunt dbl/ Vanessa Williams Christopher Erskin/Wally Crowder Haunted Mansion Stunt dbl/ Marsha Thomason Rob Minkoff/Doug Coleman Generated on 09/25/2021 06:53:49 pm Page 2 of 6 Carl Franklin/Bob Brown Love Don't Cost A Thing Stunt dbl/ Christina Milian Troy Beyer/Johhny Martin Kill Bill Stunt dbl/ Vivica A. -

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) PAUL SPARKS

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) Riley Keough, 26, is one of Hollywood’s rising stars. At the age of 12, she appeared in her first campaign for Tommy Hilfiger and at the age of 15 she ignited a media firestorm when she walked the runway for Christian Dior. From a young age, Riley wanted to explore her talents within the film industry, and by the age of 19 she dedicated herself to developing her acting craft for the camera. In 2010, she made her big-screen debut as Marie Currie in The Runaways starring opposite Kristen Stewart and Dakota Fanning. People took notice; shortly thereafter, she starred alongside Orlando Bloom in The Good Doctor, directed by Lance Daly. Riley’s memorable work in the film, which premiered at the Tribeca film festival in 2010, earned her a nomination for Best Supporting Actress at the Milan International Film Festival in 2012. Riley’s talents landed her a title-lead as Jack in Bradley Rust Gray’s werewolf flick Jack and Diane. She also appeared alongside Channing Tatum and Matthew McConaughey in Magic Mike, directed by Steven Soderbergh, which grossed nearly $167 million worldwide. Further in 2011, she completed work on director Nick Cassavetes’ film Yellow, starring alongside Sienna Miller, Melanie Griffith and Ray Liota, as well as the Xan Cassavetes film Kiss of the Damned. As her camera talent evolves alongside her creative growth, so do the roles she is meant to play. Recently, she was the lead in the highly-anticipated fourth installment of director George Miller’s cult- classic Mad Max - Mad Max: Fury Road alongside a distinguished cast comprising of Tom Hardy, Charlize Theron, Zoe Kravitz and Nick Hoult. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16 A70 TV Acad Ad.Qxp Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16_A70_TV_Acad_Ad.qxp_Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1 PROUD MEMBER OF »CBS THE TELEVISION ACADEMY 2 ©2016 CBS Broadcasting Inc. MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER AS THE QUANTITY AND QUALITY OF CONTENT HAVE INCREASED in what is widely regarded as television’s second Golden Age, so have employment opportunities for the talented men and women who create that programming. And as our industry, and the content we produce, have become more relevant, so has the relevance of the Television Academy increased as an essential resource for television professionals. In 2015, this was reflected in the steady rise in our membership — surpassing 20,000 for the first time in our history — as well as the expanding slate of Academy-sponsored activities and the heightened attention paid to such high-profile events as the Television Academy Honors and, of course, the Creative Arts Awards and the Emmy Awards. Navigating an industry in the midst of such profound change is both exciting and, at times, a bit daunting. Reimagined models of production and distribution — along with technological innovations and the emergence of new over-the-top platforms — have led to a seemingly endless surge of creativity, and an array of viewing options. As the leading membership organization for television professionals and home to the industry’s most prestigious award, the Academy is committed to remaining at the vanguard of all aspects of television. Toward that end, we are always evaluating our own practices in order to stay ahead of industry changes, and we are proud to guide the conversation for television’s future generations. -

The First Amendment Implications of Convergence

Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 9 Volume IX Number 2 Volume IX Book 2 Article 3 1999 Panel I: The First Amendment Implications of Convergence Andrew Jay Schwartzman Media Access Project Nicholas Jollymore Time Inc. Janine Jaquet New York University Jonathan Zittrain Berkman Center for Internet & Society; Harvard Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Andrew Jay Schwartzman, Nicholas Jollymore, Janine Jaquet, and Jonathan Zittrain, Panel I: The First Amendment Implications of Convergence, 9 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 421 (1999). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol9/iss2/3 This Transcript is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PANEL I.TYP.DOC 9/29/2006 4:34 PM Panel I: The First Amendment Implications of Convergence Moderator: James Goodale* Panelists: Andrew Jay Schwartzman** Nicholas Jollymore*** Janine Jaquet**** Jonathan Zittrain***** MR. GOODALE: Well, I have to tell you—this is one of my more exciting moments, because I have taught a course on this very subject ever since I came to Fordham Law School. And no one could teach a more exciting course, because every year the technol- ogy changes, which means every year the law is subject to change. -

UNDENIABLE the Survey of Hostility to Religion in America

UNDENIABLE The Survey of Hostility to Religion in America 2014 Edition Editorial Team Kelly Shackelford Chairman Jeffrey Mateer Executive Editor Justin Butterfield Editor-in-chief Michael Andrews Assistant Editor Past Contributors Bryan Clegg An Open Letter to the American PEople UNDENIABLE To our fellow citizens: The Survey of Hostility to Religion in America Hostility to religion and religious freedom in America—institutional, pervasive, damaging hostility—can no longer reasonably be denied. And 2014 Edition yet there remain deniers. Because denial of these attacks is a mortal threat to the survival and health of Kelly Shackelford, chairman our republic, Liberty Institute and Family Research Council collaborated in 2012 to publish a survey documenting the frequency and severity of incidents Jeffrey Mateer, executive editor of hostility. In the 2013 survey entitled Undeniable, the research team led by Justin Butterfield, editor-in-chief a Harvard-trained constitutional attorney found almost twice the number of incidents in the previous twelve months than all the incidents found from Michael Andrews, assistant editor several years’ past. The rate of hostility was increasing at an alarming rate. This year in Undeniable: The Survey of Hostility to Religion 2014, the team Copyright © 2013–2014 Liberty Institute. of researchers again documented an alarming increase in the number of All rights reserved. hostile incidents toward religion from the year before. The rate of hostility is continuing to climb. We offer Undeniable 2014 to you, the American people, as an alarm bell This publication is not to be used for legal advice. Because the law is ringing in the night. We believe the many public opinion surveys showing constantly changing and each factual situation is unique, Liberty Institute that you, the people, are still a religious people. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

Thirty-Third Sunday in Ordinary Time NOVEMBER 15 2020

Thirty-third Sunday in ordinary time NOVEMBER 15 2020 WELCOME Mass AT T H E CAT H E D R A L Daily 12:05pm and Sunday Masses have resumed. All Masses are limited capacity. 7am Daily Masses have NOT resumed. Saturday, Nov 14 12:05pm Daily Mass—Church † Donald & Mary Lintner 4:30pm Sunday Vigil Mass—Church † Elmer & Mildred Lintner Sunday, Nov 15 10:00am Sunday Mass—Church (televised|live‐streamed) ALS Interpretaon † Ted Hauser 12:00pm Misa Dominical en Español—Iglesia Familia Parroquial 5:30pm Sunday Mass—Church † Sam Macaluso 7:30pm Sunday Contemplave Mass—Church † Fr. Dennis Morrow Monday, Nov 16 12:05pm Daily Mass—Church † James Philips Oleck Tuesday, Nov 17 12:05pm Daily Mass—Church Int. Gabriela Cochrane Wednesday, Nov 18 12:05pm Daily Mass—Church Int. Orlando & Enid Benedict Thursday, Nov 19 12:05pm Daily Mass—Church Int. Andrea Creswick Friday, Nov 20 12:05pm Daily Mass—Church Int. Novakoski family Saturday, Nov 21 12:05pm Daily Mass—Church 4:30pm Sunday Vigil Mass—Church † Joseph & Catherine Wojkowski Sunday, Nov 22 10:00am Sunday Mass—Church (televised|live‐streamed) ALS Interpretaon † Don Jandernoa 12:00pm Misa Dominical en Español—Iglesia Familia Parroquial 5:30pm Sunday Mass—Church † Samantha Pas 7:30pm Sunday Contemplave Mass—Church † Michael Monica & † Gregory Monica Confession schedule: Weekdays Confessions follow 12:05pm Mass Saturdays Confessions 11‐11:45am in Chapel God bless, (or by appointment) Very Rev. René Constanza, CSP Rector Watch Sunday 10am Mass Online page 2 Go to grdiocese.org or the Cathedral’s Facebook page Scripture Reading.. -

Exhibit C Form 10-K, Annual Report of Comcast

FILED 4-11-14 04:59 PM A1404013 Exhibit C Form 10-K, Annual Report of Comcast Corporation (February 12, 2014) Form 10-K Page 1 of 190 10-K 1 d666576d10k.htm FORM 10-K Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) _ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2013 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM TO Registrant; State of Incorporation; Address and Commission File Number Telephone Number I.R.S. Employer Identification No. 001-32871 COMCAST CORPORATION 27-0000798 PENNSYLVANIA One Comcast Center Philadelphia, PA 19103-2838 (215) 286-1700 333-174175 NBCUniversal Media, LLC 14-1682529 DELAWARE 30 Rockefeller Plaza New York, NY 10112-0015 (212) 664-4444 SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OF THE ACT: Comcast Corporation – Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on which Registered Class A Common Stock, $0.01 par value NASDAQ Global Select Market Class A Special Common Stock, $0.01 par value NASDAQ Global Select Market 2.0% Exchangeable Subordinated Debentures due 2029 New York Stock Exchange 5.00% Notes due 2061 New York Stock Exchange 5.50% Notes due 2029 New York Stock Exchange 9.455% Guaranteed Notes due 2022 New York Stock Exchange NBCUniversal Media, LLC – NONE SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(g) OF THE ACT: Comcast Corporation – NONE NBCUniversal Media, LLC – NONE Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act.