July 2019 New York State Bar Examination MEE & MPT Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Declarations-Part 1

, ";IV..JULU ;......... '''' -..... iJ 111 ~ ~, CONOOPlIl'IIU!1 DECLARATION GOLDeN RI DGE. CONOOH IN! UHS WDeX Title Section No. Page No. Submis.;on to Condominium CMnersh!p, .............. 1 ........... C1!!finitions •••••• ~~.~ •• ~. ~" •• _ ~ ~ •• ,,~ ••• ~~ ••• ~. ~.# .2. ~ ..... 6.,."" Divi.ion of Property in the Condominium Units and Conveyance of Unit6 ••••.•••...••....• 3 .••.• $ •••• ~. 3 Limited Common Element5 ••••• ~.6 ••• " •••••••• 4" •••••• 4."' ........... 4; Description of Condcninium Unit •• W ...... H •••• ~.H.S ........ "'.H ... '" Condom!n!= ~ap ................................... 6 ............ 5 lnsepl'lt'Jibility of a Condominium Unit. •••• " ......... 7 •• ~ .......... " 5 Repsrate Assersment and Taxation - Noticb' to A5sesBor .............................. 6 •••••••••••• 6 Porm of O\tnership - Title ...... ~ ... ~ •••••••• ~ ••••••. 9 ....... ~.~ •• ~ 6 Non-Pr.rtitionability Bnd Transfer of. ~mrncn element.~~ ......... ~ ... ., •• e ......... * ••••• ~10 .. .,~~~ .... ~ .. " .... 6 Common Ele1lent.5 .............. ~ ............. ~ ......... ,,~ .. 11 .............. ~ .. 6 Use and Occupancy .............................. $ ........................ 12 ..... , " .. .. .. .. .. .... 6 Ea8ements ........................................... 1) .• ~ ..... ., .. ~ .. 7 Termination of Mechanlc l g Lien Rights and Indemnification •••••••••••••....•.. 14 .••••••••••• S C-olden Ridge CondGnliiniurt Association, IfiC ••••• q .. j5 •• ~ ............ "' ... 8 Re8ervation for Access - Maintenance, Repair Bnd Emergenciea~"'""'~~~,.~"' -

The Rule Against Perpetuities and Its Application to a Private Trust

Cleveland State Law Review Volume 1 Issue 2 Article 7 1952 The Rule Against Perpetuities and Its Application to a Private Trust Reuben M. Payne Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Reuben M. Payne, The Rule Against Perpetuities and Its Application toa Private Trust, 1(2) Clev.-Marshall L. Rev. 59 (1952) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland State Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rule Against Perpetuities and Its Application to a Private Trust by Reuben M. Payne* T ESTATOR DEVISED certain real property to his daughter in fee. Thereafter he executed a codicil whereby said devise was re- voked and the same property was devised to his son-in-law, in trust. Trustee was to hold it in trust for testator's daughter during the term of her life and in the event of death of daughter, son-in- law was to take possession of property, lease it, and use rents for support, education and benefits of the children of daughter. Daughter survived testator and gave birth to two additional children after testator's death. Held: the trust the testator at- tempted to create in his codicil was void as in violation of the Rule Against Perpetuities, where daughter survived testator and gave birth to two additional children after testator's death.' The court's decision is that a trust for private purpose must terminate within the period of the Rule Against Perpetuities. -

Preemptive Narratives in Recent Television Series Par Toni Pape

Université de Montréal Figures of Time: Preemptive Narratives in Recent Television Series par Toni Pape Département de littérature comparée, Faculté des arts et des sciences Thèse présentée à la Faculté des arts et des sciences en vue de l’obtention du grade de Ph. D. en Littérature, option Études littéraires et intermédiales Juillet 2013 © Toni Pape, 2013 Résumé Cette thèse de doctorat propose une analyse des temporalités narratives dans les séries télévisées récentes Life on Mars (BBC, 2006-2007), Flashforward (ABC, 2009-2010) et Damages (FX/Audience Network, 2007-2012). L’argument général part de la supposition que les nouvelles technologies télévisuelles ont rendu possible de nouveaux standards esthétiques ainsi que des expériences temporelles originales. Il sera montré par la suite que ces nouvelles qualités esthétiques et expérientielles de la fiction télévisuelle relèvent d’une nouvelle pertinence politique et éthique du temps. Cet argument sera déployé en quatre étapes. La thèse se penche d’abord sur ce que j’appelle les technics de la télévision, c’est-à- dire le complexe de technologies et de techniques, afin d’élaborer comment cet ensemble a pu activer de nouveaux modes d’expérimenter la télévision. Suivant la philosophie de Gilles Deleuze et de Félix Guattari ainsi que les théories des médias de Matthew Fuller, Thomas Lamarre et Jussi Parikka, ce complexe sera conçu comme une machine abstraite que j’appelle la machine sérielle. Ensuite, l’argument puise dans des théories de la perception et des approches non figuratives de l’art afin de mieux cerner les nouvelles qualités d’expérience esthétique dans la fiction sérielle télévisée. -

LIFE ESTATES and PRECATORY TRUSTS A. Creation of Life Estate

LIFE ESTATES AND PRECATORY TRUSTS A. Creation of Life Estate upon Passing of Decedent. According to the Official Code of Georgia Annotated (O.C.G.A.) § 44-6-80, estates that “extend during the life of a person but terminate at the death of the person are deemed life estates.”1 A life estate may be created by “deed or will” so long as the life estate does not exist in property that “will be destroyed [upon] being used.”2 Additionally, the life estate may last for the life of the tenant or for the life of some other person.3 Thus, the tenant of the life estate is entitled to the “full use and enjoyment of the property” so long as the life tenant is alive.4 When the life tenant passes, the life estate terminates and the right to present use or possession of the property will pass to either the “estate in remainder” or the “estate in reversion.”5 An estate in remainder is present if a party, other than the grantor and/or his heirs, receives the right to the use and the enjoyment of the property after termination of the the life estate.6 An estate in reversion exists if the right to use or enjoyment reverts back to the grantor and his heirs.7 Despite the legal distinction, the rights of the reversioner are the same as those of a vested remainderman in fee in Georgia.8 There is no technical requirement regarding what type of language is necessary for a testator to create a remainder. -

The Rule Against Perpetuities: a Survey of State (And D.C.) Law

THE RULE AGAINST PERPETUITIES: A SURVEY OF STATE (AND D.C.) LAW At common law, the rule against perpetuities provided that: No [nonvested property] interest is good unless it must vest, if at all, not later than 21 years after some life in being at the creation of the interest. Gray, The Rule Against Perpetuities § 201 (4th ed. 1942). Under the common law rule, the interest was invalid unless it was certain on the date the interest was created that it would vest within 21 years after the death of the last designated life in being at that time (the “common law period”). The common law rule ignored any events that occurred after the interest was created, and focused only on what was certain to occur or not to occur when the interest was created. The common law rule remains intact in only three states, however – Alabama, New York, and Texas. Three more states – Iowa, Mississippi and Oklahoma – have the common law rule, with the “wait-and-see” modification that determines whether an interest was valid based on whether it actually vested within the common law period, rather than whether it had to do so in all events. The beginning of the movement away from the common law rule began in 1979, when the Restatement (Second) of Property suggested that this approach was unreasonable, because it ignored events that, in some cases, had already occurred before the court or the parties had to determine the validity of the interests created. Restatement The Rule Against Perpetuities, 50-State Survey, Page 1 DISCLAIMER ON USE: The reader is cautioned to confirm the information provided in this Survey by independent research and analysis to ensure that it is accurate, complete, and current. -

Rule Against Perpetuities

Sec. 2 ESTATES IN LAND AND FUTURE INTERESTS S229 3. The court mentions three possible constructions that could be placed on the “deed.” Under which one, if any, could Clarissa B. collect? Can you think of any other plausible constructions? Review the Note on the Words of Conveyance, supra, p. S167. 4. Once the court had decided that instrument was a deed and not a will, there are a number of possible constructions that could be placed on the interest which was given Clarissa B. The court distinguishes this conveyance from one granting a contingent remainder to Clarissa B., reserving a life estate in her husband. (Do you see how?) Yet ample authority exists for the proposition that an otherwise valid deed, stating that it is not to be effective until the death of the grantor, will be upheld, as reserving a life estate in the grantor and conveying a remainder in the grantee. 3 A.L.P. §§ 12.65, 12.95 n. 5. What interest does the court decide that Clarissa B. had? What are the possibilities? 4. The Rule Against Perpetuities At about the same time as the courts were reviving the doctrine of destructibility of contingent remainders, they also began to announce another doctrine which came to be known as the Rule Against Perpetuities. The first case in which the Rule was announced is generally thought to be the Duke of Norfolk’s Case, 3 Ch. Cas. 1, 22 Eng. Rep. 931 (1682). The reason for the origin of the Rule probably lies in the courts’ concern with the free alienability of land. -

Listing Appointment Checklist

75-hour New York Prelicense Course Syllabus Course Description This Pre-License course focuses on New York Real Estate Law and the everyday practice of Real Estate approved by the New York Real Estate Commission. This course covers all the subjects mandated by New York Real Estate License Law, for those interested in gaining their license. This course is expressly designed for, and geared to, all those potential licensees as defined by the New York Real Estate Commission, for the purpose of sitting for the real estate salesperson's exam. Anyone who assists or desires to assist others in the sale, leasing, management, or exchange of real estate must hold at least a real estate salesperson's license. Course Learning Objectives Unit 1: License Law Overview and Procedures for Licensing 1. State the purpose of the NY licensing law, the Department of State and the Board of Real Estate. 2. Explain the rules for obtaining a license in New York, state the types of licenses and their respective requirements. 3. Explain the New York real estate licensing exam requirements, procedures and policies. Unit 2: License Law Rules and Regulations 1. Define and explain the rules for license issuance, license information changes and branch office management. 2. Define and explain the rules for license renewal, continuing education and reciprocity. 3. Identify at least five Department regulations including handling of kickbacks and proper advertising. Unit 3: Unlicensed Assistants and License Law Violations 1. Name three allowed and three prohibited activities for unlicensed assistants and list at least five licensee activities that violate NY license law. -

14-99-00172-Cv ______

Affirmed and Opinion filed May 3, 2001. In The Fourteenth Court of Appeals ____________ NO. 14-99-00172-CV ____________ PATRICIA A. GAIDES, Appellant V. FRANK CARL GAIDES, Appellee On Appeal from the 309th District Court Harris County, Texas Trial Court Cause No. 94-24154 O P I N I O N Appellant, Patricia A. Gaides, appeals from a judgment dividing the marital estate in her divorce from appellee, Frank Carl Gaides. Patricia contends in five issues that the trial court erred by: (1) refusing to divide the community estate disproportionately; (2) valuing community property improperly; (3) mischaracterizing separate property as community property; (4) failing to reimburse the community estate for alleged waste; and (5) exceeding its authority by ordering a division of the probate estate of the Gaides’ son. We affirm. FACTUAL AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND Patricia A. Gaides and Frank Carl Gaides were married on February 8, 1964. The couple had three children, born in 1967, 1970, and 1974. Following the birth of their first child, only Frank worked outside the home, while Patricia had primary responsibility for the children’s care. In 1988, the couple separated, prompted by Patricia’s discovery that Frank was having an affair. Frank continued to deposit his paychecks into an account accessible to Patricia until March 1992, after which Patricia paid her living expenses through community accounts. In May 1994, Patricia initiated divorce proceedings. The case was tried to the court, which heard eleven days of testimony spanning a period from May through November, 1997.1 The trial court entered a Final Decree of Divorce on November 13, 1998, that included a division of property. -

Property Ownership in Kansas Forrest Buhler, Staff Attorney Kansas Agricultural Mediation Services

Property Ownership in Kansas Forrest Buhler, Staff Attorney Kansas Agricultural Mediation Services I. Two general categories—Real and Personal property A. Real property. Real property includes land, attached structures, and mineral rights. B. Personal property. Personal property includes both tangible and intangible property. 1. Tangible personal property includes such things as household goods, automobiles, business or farm equipment, livestock, and stored grain. 2. Intangible personal property includes bank deposits, life insurance policies, stocks and bonds. II. Types of title ownership A. Fee Simple Absolute. The owner (or owners) generally has the power to sell, borrow against, receive income from, lease, and transfer property to others during life of the owner or at death. B. Life Estates and Remainder Interests. Holders of a life estate—the life tenants—share property interests with “remaindermen” (the persons designated to receive a transfer of the property after death of the life tenant). 1. Life tenants manage and receive income from the property during their lifetimes, but cannot dispose of it at death. 2. Life tenants generally may not sell or mortgage the property without the permission of the remainderman and are generally responsible for property taxes, mortgage payments, and property maintenance. 3. It is important to note that the terms and provisions of a life estate may vary, depending on the instrument creating it. C. Sole Ownership. With sole ownership, only one name appears on the deed or title. All solely owned property becomes a part of the owner’s gross estate and upon death, passes to named beneficiaries under a will or to heirs according to Kansas intestate laws (where there is no will). -

EVICTION for TENANTS an Informational Guide to a North Dakota Civil Court Process

EVICTION FOR TENANTS An Informational Guide to a North Dakota Civil Court Process The North Dakota Legal Self Help Center provides resources to people who represent themselves in civil matters in the North Dakota state courts. The information provided in this informational guide isn’t intended for legal advice but only as a general guide to a civil court process. If you decide to represent yourself, you’ll need to do additional research to prepare. When you represent yourself, you’re expected to know and follow the law, including: • State or federal laws that apply to your case; • Case law, also called court opinions, that applies to your case; and • Court rules that apply to your case, which may include: o North Dakota Rules of Civil Procedure; o North Dakota Rules of Court; o North Dakota Rules of Evidence; o North Dakota Administrative Rules and Orders; o Any local court rules. Links to the laws, case law, and court rules can be found at www.ndcourts.gov. A glossary with definitions of legal terms is available at www.ndcourts.gov/legal-self-help. When you represent yourself, you’re held to same requirements and responsibilities as a lawyer, even if you don’t understand the rules or procedures. If you’re unsure if this information suits your circumstances, consult a lawyer. • If you would like to learn more about finding a lawyer to represent you, go to www.ndcourts.gov/legal-self-help/finding-a-lawyer. This information isn’t a complete statement of the law. This covers basic information about the process of eviction in a North Dakota State District Court from a tenant’s perspective. -

Notes from the Midnight Driver

Notes From the Midnight Driver Jordan Sonnenblick SCHOLASTIC INC. New York Toronto London Auckland Sydney Mexico City New Delhi Hong Kong Buenos Aires To my grandfather, Solomon Feldman, who inspired this book, and to the memory of my father, Dr. Harvey Sonnenblick, who loved it Table of Contents Title Page Dedication May Last September Gnome Run The Wake-Up Day Of The Dork-Wit My Day In Court Solomon Plan B Laurie Meets Sol Sol Gets Interested Half An Answer Happy Holidays The Ball Falls Happy New Year! Enter The Cha-Kings Home Again Am I A Great Musician, Or What? A Night For Surprises Darkness The Valentine’s Day Massacre Good Morning, World! The Mission The Saints Go Marchin’ In The Work Of Breathing Peace In My Tribe Finale Coda The Saints Go Marchin’ In Again Thank you Notes About the Author Interview Sneak Peek Copyright May Boop. Boop. Boop. I’m sitting next to the old man’s bed, watching the bright green line spike and jiggle across the screen of his heart monitor. Just a couple of days ago, those little mountains on the monitor were floating from left to right in perfect order, but now they’re jangling and jerking like maddened hand puppets. I know that sometime soon, the boops will become one long beep, the mountains will crumble into a flat line, and I will be finished with my work here. I will be free. LAST SEPTEMBER GNOME RUN It seemed like a good idea at the time. Yes, I know everybody says that—but I’m serious. -

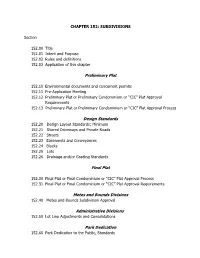

Preliminary Plat Design Standards Final Plat Metes and Bounds

CHAPTER 152: SUBDIVISIONS Section 152.00 Title 152.01 Intent and Purpose 152.02 Rules and definitions 152.03 Application of this chapter Preliminary Plat 152.10 Environmental documents and concurrent permits 152.11 Pre-Application Meeting 152.12 Preliminary Plat or Preliminary Condominium or “CIC” Plat Approval Requirements 152.13 Preliminary Plat or Preliminary Condominium or “CIC” Plat Approval Process Design Standards 152.20 Design Layout Standards; Minimum 152.21 Shared Driveways and Private Roads 152.22 Streets 152.23 Easements and Conveyances 152.24 Blocks 152.25 Lots 152.26 Drainage and/or Grading Standards Final Plat 152.30 Final Plat or Final Condominium or “CIC” Plat Approval Process 152.31 Final Plat or Final Condominium or “CIC” Plat Approval Requirements Metes and Bounds Divisions 152.40 Metes and Bounds Subdivision Approval Administrative Divisions 152.50 Lot Line Adjustments and Consolidations Park Dedication 152.60 Park Dedication to the Public, Standards Required Improvements 152.70 General Improvement Provisions 152.71 Survey Standards 152.72 Street Improvement Standards 152.73 Sanitary Provision Standards 152.74 Water Supply Standards Developer Responsibilities 152.80 Payment for Installation of Improvements 152.81 Required Agreement for Installation of Improvements 152.82 Financial Guarantee 152.83 Construction Standards Administration 152.90 Amendments 152.91 PUD 152.92 Variance to Subdivision Standards 152.93 Recording of Divisions 152.94 Administrative Fees CHAPTER 152: SUBDIVISIONS § 152.00 TITLE. This chapter shall be referred to and cited as The Breezy Point Subdivision Ordinance, except herein where it shall be cited as the “chapter”. § 152.01 INTENT AND PURPOSE.