Rest in Pieces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gossip, Exclusion, Competition, and Spite: a Look Below the Glass Ceiling at Female-To-Female Communication Habits in the Workplace

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2013 Gossip, Exclusion, Competition, and Spite: A Look Below the Glass Ceiling at Female-to-Female Communication Habits in the Workplace Katelyn Elizabeth Brownlee [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Organizational Communication Commons Recommended Citation Brownlee, Katelyn Elizabeth, "Gossip, Exclusion, Competition, and Spite: A Look Below the Glass Ceiling at Female-to-Female Communication Habits in the Workplace. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2013. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1597 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Katelyn Elizabeth Brownlee entitled "Gossip, Exclusion, Competition, and Spite: A Look Below the Glass Ceiling at Female-to-Female Communication Habits in the Workplace." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Communication and Information. Michelle Violanti, Major Professor We have read this thesis -

Netflix Adds to Original Shows with Sony Deal 15 October 2013

Netflix adds to original shows with Sony deal 15 October 2013 programming to make itself a preferred location for on-demand streaming. "We were spellbound after hearing Todd, Glenn and Daniel's pitch, and knew Netflix was the perfect home for this suspenseful family drama that is going to have viewers on the edge of their seats," said Netflix vice president of original content Cindy Holland. Netflix scored a recent hit with its political drama "House of Cards," tossing conventional TV wisdom out the window when it released a full season in one fell swoop early this year. The Netflix company logo is seen at Netflix headquarters The series, which was nominated for a 2013 Emmy in Los Gatos, CA on Wednesday, April 13, 2011 for best drama, joins a recent spate of original Netflix programming that includes new episodes of "Arrested Development," plus the series "Orange is the New Black" and "Hemlock Grove." Netflix on Monday announced a deal with Sony to create a psychological thriller series for the online Netflix sees original programming as part of a streaming and DVD service, ramping up original formula to gain and hold subscribers at its $7.99-a- programming to win subscribers. month fee that covers a vast catalog of pre- released TV shows and movies. "Damages" creators Todd Kessler, Daniel Zelman, and Glenn Kessler will begin production of a © 2013 AFP 13-episode first season of the show from Sony Pictures Television early next year. The yet-unnamed series will broadcast exclusively on Netflix, according to the California-based Internet company. -

The Rise of the Anti-Hero: Pushing Network Boundaries in the Contemporary U.S

The Rise of The Anti-Hero: Pushing Network Boundaries in The Contemporary U.S. Television YİĞİT TOKGÖZ Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in CINEMA AND TELEVISION KADIR HAS UNIVERSITY June, 2016 I II ABSTRACT THE RISE OF THE ANTI-HERO: PUSHING NETWORK BOUNDARIES IN THE CONTEMPORARY U.S. TELEVISION Yiğit Tokgöz Master of Arts in Cinema and Television Advisor: Dr. Elif Akçalı June, 2016 The proliferation of networks using narrowcasting for their original drama serials in the United States proved that protagonist types different from conventional heroes can appeal to their target audiences. While this success of anti-hero narratives in television serials starting from late 1990s raises the question of “quality television”, developing audience measurement models of networks make alternative narratives based on anti-heroes become widespread on the U.S. television industry. This thesis examines the development of the anti-hero on the U.S. television by focusing on the protagonists of pay-cable serials The Sopranos (1999-2007) and Dexter (2006-2013), basic cable serials The Shield (2002-2008) and Mad Men (2007-2015), and video-on-demand serials House of Cards (2013- ) and Hand of God (2014- ). In brief, this thesis argues that the use of anti-hero narratives in television is directly related to the narrowcasting strategy of networks and their target audience groups, shaping a template for growing networks and newly formed distribution services to enhance the brand of their corporations. In return, the anti-hero narratives push the boundaries of conventional hero in television with the protagonists becoming morally less tolerable and more complex, introducing diversity to television serials and paving the way even for mainstream broadcast networks to develop serials based on such protagonists. -

Preemptive Narratives in Recent Television Series Par Toni Pape

Université de Montréal Figures of Time: Preemptive Narratives in Recent Television Series par Toni Pape Département de littérature comparée, Faculté des arts et des sciences Thèse présentée à la Faculté des arts et des sciences en vue de l’obtention du grade de Ph. D. en Littérature, option Études littéraires et intermédiales Juillet 2013 © Toni Pape, 2013 Résumé Cette thèse de doctorat propose une analyse des temporalités narratives dans les séries télévisées récentes Life on Mars (BBC, 2006-2007), Flashforward (ABC, 2009-2010) et Damages (FX/Audience Network, 2007-2012). L’argument général part de la supposition que les nouvelles technologies télévisuelles ont rendu possible de nouveaux standards esthétiques ainsi que des expériences temporelles originales. Il sera montré par la suite que ces nouvelles qualités esthétiques et expérientielles de la fiction télévisuelle relèvent d’une nouvelle pertinence politique et éthique du temps. Cet argument sera déployé en quatre étapes. La thèse se penche d’abord sur ce que j’appelle les technics de la télévision, c’est-à- dire le complexe de technologies et de techniques, afin d’élaborer comment cet ensemble a pu activer de nouveaux modes d’expérimenter la télévision. Suivant la philosophie de Gilles Deleuze et de Félix Guattari ainsi que les théories des médias de Matthew Fuller, Thomas Lamarre et Jussi Parikka, ce complexe sera conçu comme une machine abstraite que j’appelle la machine sérielle. Ensuite, l’argument puise dans des théories de la perception et des approches non figuratives de l’art afin de mieux cerner les nouvelles qualités d’expérience esthétique dans la fiction sérielle télévisée. -

Nomination Press Release

Brian Boyle, Supervising Producer Outstanding Voice-Over Nahnatchka Khan, Supervising Producer Performance Kara Vallow, Producer American Masters • Jerome Robbins: Diana Ritchey, Animation Producer Something To Dance About • PBS • Caleb Meurer, Director Thirteen/WNET American Masters Ron Hughart, Supervising Director Ron Rifkin as Narrator Anthony Lioi, Supervising Director Family Guy • I Dream of Jesus • FOX • Fox Mike Mayfield, Assistant Director/Timer Television Animation Seth MacFarlane as Peter Griffin Robot Chicken • Robot Chicken: Star Wars Episode II • Cartoon Network • Robot Chicken • Robot Chicken: Star Wars ShadowMachine Episode II • Cartoon Network • Seth Green, Executive Producer/Written ShadowMachine by/Directed by Seth Green as Robot Chicken Nerd, Bob Matthew Senreich, Executive Producer/Written by Goldstein, Ponda Baba, Anakin Skywalker, Keith Crofford, Executive Producer Imperial Officer Mike Lazzo, Executive Producer The Simpsons • Eeny Teeny Maya, Moe • Alex Bulkley, Producer FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Corey Campodonico, Producer Century Fox Television Hank Azaria as Moe Syzlak Ollie Green, Producer Douglas Goldstein, Head Writer The Simpsons • The Burns And The Bees • Tom Root, Head Writer FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Hugh Davidson, Written by Century Fox Television Harry Shearer as Mr. Burns, Smithers, Kent Mike Fasolo, Written by Brockman, Lenny Breckin Meyer, Written by Dan Milano, Written by The Simpsons • Father Knows Worst • FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Kevin Shinick, -

Rose Byrne Under Wraps How She Charmed the World with Her Hidden Talent

JULY 31, 2016 + TALL ORDER: DOES YOUR DATE MEASURE UP? SHIFT YOUR CAREER UP A GEAR DECADENT PEANUT BUTTER DESSERTS ROSE BYRNE UNDER WRAPS HOW SHE CHARMED THE WORLD WITH HER HIDDEN TALENT SNS31JUL16p001 1 22/07/16 3:27 PM (cover_story) Roses She’s no garden-variety star. Rose Byrne is now in full bloom as a sought-after comic actor, says Tiffany Bakker 10 | SUNDAYSTYLE.COM.AU 11 SVS31JUL16p010 10 22/07/16 4:48 PM ose Byrne is pondering like I’m a big name,” she says. “I feel like her day job. “Acting is I’ve been very lucky in the people I’ve embarrassing, absolutely,” been able to work with.” she says, with a hearty laugh. In recent years, of course, there has R“Just the vulnerability it requires, whether been her much-vaunted emergence as in a performance or doing interviews. It’s a big-screen comedy superstar (more an odd thing, and it’s also a bit of a silly job. on that later), but she has just as easily I mean, it’s a great job, and I take it navigated indie drama (Adult Beginners), seriously and I’m passionate about it, but dramedy (The Meddler), horror (Insidious), I know I’m not curing cancer, so you have musicals (Annie), tent-pole franchises (the to have some perspective on it.” X-Men series), and television (Damages). When we meet, Byrne is mid-pedicure Ask her to reflect on her extraordinary at a downtown New York hotel, apologising success and she squirms slightly. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Drama | 60 Minutes DAWSON’S CREEK TEENAGE FRIENDS COME of AGE in a SMALL Resort TOWN

MAD ABOUT YOU ....................................................3 my boys ....................................................4 married with children ....................................................5 THE nanny ....................................................6 men at work ....................................................7 WHO’S THE BOSS? ....................................................7 the king of queens ....................................................8 RULES OF ENGAGEMENT ....................................................8 THE JEFFERSONS ....................................................9 SILVER SPOONS ....................................................9 DIFF’RENT STROKES ..................................................10 I DREAM OF JEANNIE ..................................................10 •3• comedy Paul is a documentary film-maker with a penchant for obsessing over the minutae, and his wife Jamie is a fiery public relations specialist. Together, these two young, urban newlyweds try to A SOPHISTICATED MARRIED COUPLE NAVIGATE sustain wedded bliss despite the demands of their respective professional careers, meddling MAD ABOUT YOU THE CHALLENGES OF MARRIAGE AND PARENTHOOD. friends (like Fran Devanow, Jamie’s first boss and eventual best friend, Ira, Paul’s cousin, and Lisa, Jamie’s offbeat older sister) in the chaos of big city living… always with honesty and humor. view promo comedy | 30 minutes •4• comedy MY BOYS A FEMALE SPORTS COLUMNIST DEALS WITH THE MEN IN HER LIFE comedy | 30 minutes view promo INCLUDING -

Damages – the Complete Series – Blu-Ray

DAMAGES – THE COMPLETE SERIES – BLU-RAY Short Synopsis: For five extraordinary seasons, DAMAGES, the critically acclaimed legal thriller, broke all the rules and made its own. Film legend Glenn Close won two Emmys® for her stunning portrayal of relentless litigator Patty Hewes, who commands the courtroom and the screen, doing battle with ambitious protégée - turned-adversary Ellen Parsons (Rose Byrne) in cutting-edge cases with devastating consequences both professional and personal. Target Audience: Fans of The Good Wife, Revenge, Scandal, Homeland Notable Cast/Crew: Glenn Close, Rose Byrne Guest Stars include: Ted Danson, Tate Donovan, William Hurt, Marcia Gay Harden, Lily Tomlin, Martin Short, John Goodman, Jenna Elfman, Timothy Olyphant, Chris Messina, Campbell Scott and Ryan Phillippe Key selling points: • Nominated for 20 Emmy® awards with 4 wins including consecutive Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series awards for Glenn Close • Glenn Close has been selected as the 2018 honoree of New York’s Museum of Moving Image 32nd annual salute (past honorees include Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Jimmy Stewart) • Glenn Close is one of the most acclaimed actresses of our times – 6 Oscar® nominations, 12 Golden Globes, 12 Emmys and 4 Tonys. • Created by Glenn & Todd Kessler and Daniel Zelman who are also known for the Netflix series Bloodline • Each season is inspired by real events: Season 1, the 2001 Enron scandal. Season 2, the 2001 California Energy Crisis. Season 3, the 2009 Bernie Madoff Ponzi Scheme. Season 4, the private military company Blackwater. Season 5, WikiLeaks and its founder Julian Assange. Clip Link: https://youtu.be/qPveoJJfpcg Website Link: https://www.millcreekent.com/damages-the-complete-series-blu-ray.html Title UPC Item # Format Genre SRP Aspect Ratio Rating Runtime # Disc Damages – The Complete Series – Blu-ray 683904633361 63336 Blu-ray TV – Drama $99.98 Widescreen TV-MA 46 hr 17 min 10. -

DAVID TUTTMAN Director of Photography Davidtuttman.Com

DAVID TUTTMAN Director of Photography davidtuttman.com PROJECTS DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS WU-TANG: AN AMERICAN SAGA Various Directors HULU / 20TH CENTURY STUDIOS Season 2 IMAGINE TELEVISION Gail Barringer, Alex Tse, RZA BLINDSPOT Mark Pellington NBC / WARNER BROS Seasons 1 – 4 Marcos Siega Martin Gero, Greg Berlanti Karen Gaviola Sarah Schechter, Chad McQuay Rob Hardy Various Directors LUKE CAGE Steve Surjik NBC / MARVEL / ABC TV Series — Jamaica Unit Cheo Hodari Coker, Gail Berringer THE FOLLOWING Marcos Siega FOX / WARNER BROS Series Liz Friedlander Kevin Williamson, Michael Stricks Adam Davidson David Von Ancken Various Directors THE MYSTERIES OF LAURA McG NBC / WARNER BROS Pilot Greg Berlanti, Jeff Rake, Mike Cedar DAMAGES Dan Attias SONY Series Lawerence Trilling Todd A. Kessler, Glenn Kessler Greg Yaitanes Daniel Zelman, Mark Baker Tim Busfield Various Directors WILD CARD Tim Matheson FOX TV / USA Pilot Cary Brokaw, Stephen Godchaux Mitch Engel ROYAL PAINS Matt Penn USA / NBC UNIVERSAL Series Constantine Makris Rich Frank, Paul Frank Wendy Stanzler Andrew Lenchewski, John Rogers Allison Liddi Brown Michael Rauch, Chris Sacani, Kathy Ciric Various Directors THREE RIVERS Dan Attias CBS Pilot Carol Barbee, Curtis Hanson Carol Fenelon, Ted Gold, Randy Sutter GOSSIP GIRL Tony Wharmby CW / WARNER BROS Series Michael Fields Josh Schwartz, Stephanie Savage Various Directors Leslie Morgenstein, Bob Levy, Joe Lazarov THE WEDDING ALBUM Andy Tennant FOX Pilot Bob Greenblatt, David Janollari Wink Mordaunt, Mark Baker LAW & ORDER Jace Alexander NBC / UNIVERSAL Series Martha Mitchell Dick Wolf, Wendy Battles, Jeff Hayes David Platt Walon Green, Peter Jankowski Various Directors INNOVATIVE-PRODUCTION.COM | 310.656.5151 . -

University of Manitoba, Department of Sociology SOC 2200: Sociology

Sept. 2013 E Bowness University of Manitoba, Department of Sociology SOC 2200: Sociology through Film (A01) Fall Session 2013 3 Credit Hours Instructor: Evan Bowness, MA Class Location: 160 Dafoe Library Class Schedule: Tuesdays, 7:00 PM – 10:00 PM Course Website: https://universityofmanitoba.desire2learn.com/ Email (preferred): Through D2L (course website) Email (urgent messages only): [email protected] Phone: 204-474-8875 (voice mail checked twice a week) Office: 328 Isbister Building Office Hours: By appointment only Teaching Assistant: Jill Patterson (contact via D2L) Course Overview: Welcome to Sociology through Film—an invitation to explore themes of social inequality and social justice by using films, documentaries and television shows as a means of illustration. We begin with an introduction to the “sociological imagination” (a quality of mind that makes connections between personal troubles and public issues), and throughout the term we’ll let a projector guide us to a deeper understanding of how individuals experience social problems. You can expect to engage with a number of critical issues in sociology, and you’ll leave the course with some familiarity of the major classical and contemporary traditions of the discipline. Best of all, we’ll do this while watching movies and eating pizza. Required Reading: Kendall et al. (2012). Social Problems in a Diverse Society, Third Canadian Edition with MySocKit. 1 Sept. 2013 E Bowness Assignments and Grading: Sociological Imagination Exercise (15 %) Due October 18th by Midnight Develop your ‘Sociological Imagination’ through a short analytic writing assignment. In two pages or less, describe one or more personal troubles experienced by Claireece Jones from the film Precious (2009), and then situate it/them within the context of social problems discussed in Chapters 2, 3 and 4. -

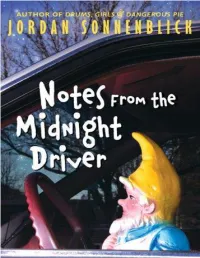

Notes from the Midnight Driver

Notes From the Midnight Driver Jordan Sonnenblick SCHOLASTIC INC. New York Toronto London Auckland Sydney Mexico City New Delhi Hong Kong Buenos Aires To my grandfather, Solomon Feldman, who inspired this book, and to the memory of my father, Dr. Harvey Sonnenblick, who loved it Table of Contents Title Page Dedication May Last September Gnome Run The Wake-Up Day Of The Dork-Wit My Day In Court Solomon Plan B Laurie Meets Sol Sol Gets Interested Half An Answer Happy Holidays The Ball Falls Happy New Year! Enter The Cha-Kings Home Again Am I A Great Musician, Or What? A Night For Surprises Darkness The Valentine’s Day Massacre Good Morning, World! The Mission The Saints Go Marchin’ In The Work Of Breathing Peace In My Tribe Finale Coda The Saints Go Marchin’ In Again Thank you Notes About the Author Interview Sneak Peek Copyright May Boop. Boop. Boop. I’m sitting next to the old man’s bed, watching the bright green line spike and jiggle across the screen of his heart monitor. Just a couple of days ago, those little mountains on the monitor were floating from left to right in perfect order, but now they’re jangling and jerking like maddened hand puppets. I know that sometime soon, the boops will become one long beep, the mountains will crumble into a flat line, and I will be finished with my work here. I will be free. LAST SEPTEMBER GNOME RUN It seemed like a good idea at the time. Yes, I know everybody says that—but I’m serious.