Crossing Languages to Play with Words the Dynamics of Wordplay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

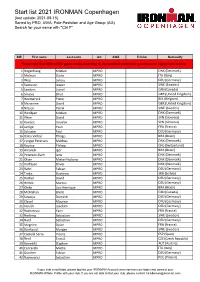

Start List 2021 IRONMAN Copenhagen (Last Update: 2021-08-15) Sorted by PRO, AWA, Pole Posistion and Age Group (AG) Search for Your Name with "Ctrl F"

Start list 2021 IRONMAN Copenhagen (last update: 2021-08-15) Sorted by PRO, AWA, Pole Posistion and Age Group (AG) Search for your name with "Ctrl F" BIB First name Last name AG AWA TriClub Nationallty Please note that BIBs will be given onsite according to the selected swim time you choose in registration oniste. 1 Hogenhaug Kristian MPRO DNK (Denmark) 2 Molinari Giulio MPRO ITA (Italy) 3 Wojt Lukasz MPRO DEU (Germany) 4 Svensson Jesper MPRO SWE (Sweden) 5 Sanders Lionel MPRO CAN (Canada) 6 Smales Elliot MPRO GBR (United Kingdom) 7 Heemeryck Pieter MPRO BEL (Belgium) 8 Mcnamee David MPRO GBR (United Kingdom) 9 Nilsson Patrik MPRO SWE (Sweden) 10 Hindkjær Kristian MPRO DNK (Denmark) 11 Plese David MPRO SVN (Slovenia) 12 Kovacic Jaroslav MPRO SVN (Slovenia) 14 Jarrige Yvan MPRO FRA (France) 15 Schuster Paul MPRO DEU (Germany) 16 Dário Vinhal Thiago MPRO BRA (Brazil) 17 Lyngsø Petersen Mathias MPRO DNK (Denmark) 18 Koutny Philipp MPRO CHE (Switzerland) 19 Amorelli Igor MPRO BRA (Brazil) 20 Petersen-Bach Jens MPRO DNK (Denmark) 21 Olsen Mikkel Hojborg MPRO DNK (Denmark) 22 Korfitsen Oliver MPRO DNK (Denmark) 23 Rahn Fabian MPRO DEU (Germany) 24 Trakic Strahinja MPRO SRB (Serbia) 25 Rother David MPRO DEU (Germany) 26 Herbst Marcus MPRO DEU (Germany) 27 Ohde Luis Henrique MPRO BRA (Brazil) 28 McMahon Brent MPRO CAN (Canada) 29 Sowieja Dominik MPRO DEU (Germany) 30 Clavel Maurice MPRO DEU (Germany) 31 Krauth Joachim MPRO DEU (Germany) 32 Rocheteau Yann MPRO FRA (France) 33 Norberg Sebastian MPRO SWE (Sweden) 34 Neef Sebastian MPRO DEU (Germany) 35 Magnien Dylan MPRO FRA (France) 36 Björkqvist Morgan MPRO SWE (Sweden) 37 Castellà Serra Vicenç MPRO ESP (Spain) 38 Řenč Tomáš MPRO CZE (Czech Republic) 39 Benedikt Stephen MPRO AUT (Austria) 40 Ceccarelli Mattia MPRO ITA (Italy) 41 Günther Fabian MPRO DEU (Germany) 42 Najmowicz Sebastian MPRO POL (Poland) If your club is not listed, please log into your IRONMAN Account (www.ironman.com/login) and connect your IRONMAN Athlete Profile with your club. -

PAPERS in NEW GUINEA LINGUISTICS No. 18

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS S e.ft-<- e..6 A - No. 4 0 PAPERS IN NEW GUINEA LINGUISTICS No. 18 by R. Conrad and W. Dye N.P. Thomson L.P. Bruce, Jr. Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Conrad, R., Dye, W., Thomson, N. and Bruce Jr., L. editors. Papers in New Guinea Linguistics No. 18. A-40, iv + 106 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1975. DOI:10.15144/PL-A40.cover ©1975 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is published by the Ling ui��ic Ci�cl e 06 Canbe��a and consists of four series: SERIES A - OCCAS IONAL PAPERS SERIES B - MONOGRAPHS SERIES C - BOOKS SERIES V - SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS . EDITOR: S.A. Wurm . ASSOCIATE EDITORS: D.C. Laycock , C.L. Voorhoeve . ALL CORRESPONDENCE concerning PACIFIC LINGUISTICS, including orders and subscriptions, should be addressed to: The Secretary, PACIFIC LINGUISTICS, Department of Linguistics, School of Pacific Studies, The Australian National University, Canberra , A.C.T. 2600. Australia . Copyright � The Authors. First published 1975 . The editors are indebted to the Australian National University for help in the production of this series. This publication was made possible by an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. National Library of Australia Card Number and ISBN 0 85883 118 X TABLE OF CONTENTS Page SOME LANGUAGE RELATIONSHIPS IN THE UPPER SEPIK REGION OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA, by Robert Conrad and Wayne Dye 1 O. INTRODUCTION 1 1 . -

Raiders of the Lost Ark

Swiss American Historical Society Review Volume 56 Number 1 Article 12 2020 Full Issue Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review Part of the European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation (2020) "Full Issue," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 56 : No. 1 , Article 12. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol56/iss1/12 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swiss American Historical Society Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. et al.: Full Issue Swiss A1nerican Historical Society REVIEW Volu1ne 56, No. 1 February 2020 Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 2020 1 Swiss American Historical Society Review, Vol. 56 [2020], No. 1, Art. 12 SAHS REVIEW Volume 56, Number 1 February 2020 C O N T E N T S I. Articles Ernest Brog: Bringing Swiss Cheese to Star Valley, Wyoming . 1 Alexandra Carlile, Adam Callister, and Quinn Galbraith The History of a Cemetery: An Italian Swiss Cultural Essay . 13 Plinio Martini and translated by Richard Hacken Raiders of the Lost Ark . 21 Dwight Page Militant Switzerland vs. Switzerland, Island of Peace . 41 Alex Winiger Niklaus Leuenberger: Predating Gandhi in 1653? Concerning the Vindication of the Insurgents in the Swiss Peasant War . 64 Hans Leuenberger Canton Ticino and the Italian Swiss Immigration to California . 94 Tony Quinn A History of the Swiss in California . 115 Richard Hacken II. Reports Fifty-Sixth SAHS Annual Meeting Reports . -

The Art of Staying Neutral the Netherlands in the First World War, 1914-1918

9 789053 568187 abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 1 THE ART OF STAYING NEUTRAL abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 2 abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 3 The Art of Staying Neutral The Netherlands in the First World War, 1914-1918 Maartje M. Abbenhuis abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 4 Cover illustration: Dutch Border Patrols, © Spaarnestad Fotoarchief Cover design: Mesika Design, Hilversum Layout: PROgrafici, Goes isbn-10 90 5356 818 2 isbn-13 978 90 5356 8187 nur 689 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 2006 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. abbenhuis06 11-04-2006 17:29 Pagina 5 Table of Contents List of Tables, Maps and Illustrations / 9 Acknowledgements / 11 Preface by Piet de Rooij / 13 Introduction: The War Knocked on Our Door, It Did Not Step Inside: / 17 The Netherlands and the Great War Chapter 1: A Nation Too Small to Commit Great Stupidities: / 23 The Netherlands and Neutrality The Allure of Neutrality / 26 The Cornerstone of Northwest Europe / 30 Dutch Neutrality During the Great War / 35 Chapter 2: A Pack of Lions: The Dutch Armed Forces / 39 Strategies for Defending of the Indefensible / 39 Having to Do One’s Duty: Conscription / 41 Not True Reserves? Landweer and Landstorm Troops / 43 Few -

The Status of the Least Documented Language Families in the World

Vol. 4 (2010), pp. 177-212 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4478 The status of the least documented language families in the world Harald Hammarström Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen and Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig This paper aims to list all known language families that are not yet extinct and all of whose member languages are very poorly documented, i.e., less than a sketch grammar’s worth of data has been collected. It explains what constitutes a valid family, what amount and kinds of documentary data are sufficient, when a language is considered extinct, and more. It is hoped that the survey will be useful in setting priorities for documenta- tion fieldwork, in particular for those documentation efforts whose underlying goal is to understand linguistic diversity. 1. InTroducTIon. There are several legitimate reasons for pursuing language documen- tation (cf. Krauss 2007 for a fuller discussion).1 Perhaps the most important reason is for the benefit of the speaker community itself (see Voort 2007 for some clear examples). Another reason is that it contributes to linguistic theory: if we understand the limits and distribution of diversity of the world’s languages, we can formulate and provide evidence for statements about the nature of language (Brenzinger 2007; Hyman 2003; Evans 2009; Harrison 2007). From the latter perspective, it is especially interesting to document lan- guages that are the most divergent from ones that are well-documented—in other words, those that belong to unrelated families. I have conducted a survey of the documentation of the language families of the world, and in this paper, I will list the least-documented ones. -

Merry Wives (Edited 2019)

!1 The Marry Wives of Windsor ACT I SCENE I. Windsor. Before PAGE's house. BLOCK I Enter SHALLOW, SLENDER, and SIR HUGH EVANS SHALLOW Sir Hugh, persuade me not; I will make a Star-chamber matter of it: if he were twenty Sir John Falstaffs, he shall not abuse Robert Shallow, esquire. SIR HUGH EVANS If Sir John Falstaff have committed disparagements unto you, I am of the church, and will be glad to do my benevolence to make atonements and compremises between you. SHALLOW Ha! o' my life, if I were young again, the sword should end it. SIR HUGH EVANS It is petter that friends is the sword, and end it: and there is also another device in my prain, there is Anne Page, which is daughter to Master Thomas Page, which is pretty virginity. SLENDER Mistress Anne Page? She has brown hair, and speaks small like a woman. SIR HUGH EVANS It is that fery person for all the orld, and seven hundred pounds of moneys, is hers, when she is seventeen years old: it were a goot motion if we leave our pribbles and prabbles, and desire a marriage between Master Abraham and Mistress Anne Page. SLENDER Did her grandsire leave her seven hundred pound? SIR HUGH EVANS Ay, and her father is make her a petter penny. SHALLOW I know the young gentlewoman; she has good gifts. SIR HUGH EVANS Seven hundred pounds and possibilities is goot gifts. Enter PAGE SHALLOW Well, let us see honest Master Page. PAGE I am glad to see your worships well. -

Investigating the Problems That Result of Using Homophones And

Sudan University of Science and Technology College of Graduate Studies College of Languages Investigating the Problems that Result of Using Homophones and Homographs among Students of the College of Languages ﺗﻘﺼﻲ اﻟﻤﺸﺎﻛﻞ اﻟﻨﺎﺟﻤﺔﻋﻦ اﺳﺘﺨﺪام اﻟﻤﻔﺮدات اﻟﻤﺘﺠﺎﻧﺴﺔ ﻟﻔﻈﺎً و ﺷﻜﻼً ﻟﺪى طﻼب ﻛﻠﯿﺔ اﻟﻠﻐﺎت A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of (M.A) in English Language (Applied Linguistics) Submitted by: Abdulraziq Mohammed Abdulraziq Ibrahim Supervised by: Dr. Hillary Marino Pitia 2018 0 CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.0 Background of the Study (Yule George, 2008) stated that, semantics is the study of the meaning of words, phrases, and sentences. In semantic analysis, there is always an attempt to focus on what the words conventionally mean rather than on what an individual speaker might want them to mean on particular occasion. This technical approach is concerned with objective on general meaning and avoids trying to account for subjective or local meaning. Linguistic semantics deals with conventional meaning conveyed by the use of words, phrases and sentences of a language. The researcher shed light on the homophones and homographs linguistic phenomena. The researcher can say homophones when two or more different forms have the same pronunciation also the term homograph is used when one form written and spoken has two or more related meaning. Homographs (literally "same writing") are usually defined as words that share the same spelling, regardless of how they are pronounced. If they are pronounced the same then they are also homophones (and homonyms) – for example, bark (the sound of a dog) and bark (the skin of a tree). -

![The Pursuit of Happiness :-) 2]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5696/the-pursuit-of-happiness-2-675696.webp)

The Pursuit of Happiness :-) 2]

THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS :-) 2] Simon Beattie CTRL+P The Pursuit of Happiness Ben Kinmont CTRL+P Honey & Wax CTRL+P On January 20, 2021, the four of us were Justin Croft CTRL+P on a Zoom call, throwing around ideas for a joint list while Ben and Heather kept an eye on the presidential inauguration. In the best American spirit, Simon suggested 'the pursuit of happiness.' And here we are. May the offerings in this list bring you joy! 3] The Pursuit of Happiness Heather O’Donnell runs Honey & Wax Simon Beattie specialises in European Booksellers in Brooklyn, New York, dealing (cross-)cultural history, with a particular primarily in literary and print history, with interest in the theatre and music. His 10th- an emphasis on cultural cross-pollination. anniversary catalogue, Anglo-German She is a founder of the annual Honey & Cultural Relations, came out last year. As Wax Book Collecting Prize, now in its fifth the founder of the Facebook group We year, an award of $1000 for an outstanding Love Endpapers, Simon also has a keen collection built by a young woman in the interest in the history of decorated paper; United States. an exhibition of his own collection is planned for 2022. He currently sits on the Council Heather serves on the ABAA Board of of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association, Governors, the faculty of the Colorado and teaches regularly at the York Antiquarian Antiquarian Book Seminar (now CABS- Book Seminar. Minnesota), and and the Yale Library Associates Trustees. She has spoken about Simon also translates, and composes. -

Journal Kept by Hugh Finlay, Surveyor of the Post Roads on the Continent of North America, During His Survey of the Post Offices

IGibrary InitifrBttg of ^tttfifaurglj Darlington Memorial Library SiJok ^S\ "^^ ,^vv mw- mm '^ 'A Journal kept by Hugh Finlay. 25 Copies No. /^. f.Uo.-t,U»-?V. 1 « 11 It a I kept by Hugh Fiiilay, Surveyor of the Post Roads on the Continent of North America, Surbeg of the post ^ffircs between Falmouth and Casco Bay in the Province of Massachusetts, and Savannah in Georgia; begun the 13th Septr. 1773 ^"d ended 26th June 1774. 1S67. Entered accordii INTRODUCTION. " Fixlay's Joubnal," a JIs. of 84 pp., written in a small, exceedingly neat, and per- fectly legible hand, bound in official vellum, and illustrated with two pen-and-ink maps, and a small vignette drawing, came into my possession in this wise. One John Hawkins, an Englishman, and a professor of the Swedenborgian faith, was sent out to this country about the year 1854, by that sect, as is supposed with a design to propagate the belief in the United States. He does not seem to have met with distinguished success, either in religious or secular matters, for while there is no record of his having made converts on the one part, it is cer- tain that having entered into business, he failed dismally on the other, and his belongings were sold at auction. Among various documents, correspondence and other writings that fell into the posses- sion of the auctioneer, was this manuscript, which was brought to me early in October last by his son, and from whom I at once purchased it, perceiving, as I thought, that it must possess some intrinsic value. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or irxiistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough. substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. in the unlikely event that tfie author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI* THE GENDER OF INANIMATE INDECLINABLE COMMON NOUNS IN MODERN RUSSIAN DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Diaima L. Murphy, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2000 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Anelya Rugaleva, Adviser — ^ Adviser Professor Daniel Collins Department of Slavic and East European Languages and Literatures Professor Brian Joseph UMI Number 9962434 UMI* UMI Microform9962434 Copyright 2000 by Bell & Howell information and Leaming Company. -

Phonological Effects in Visual Word Recognition: Investigating the Impact of Feedback Activation

Journal of Experimental Psychology: Copyright 2002 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. Learning, Memory, and Cognition 0278-7393/02/$5.00 DOI: 10.1037//0278-7393.28.3.572 2002, Vol. 28, No. 3, 572–584 Phonological Effects in Visual Word Recognition: Investigating the Impact of Feedback Activation Penny M. Pexman Stephen J. Lupker University of Calgary University of Western Ontario Lorraine D. Reggin University of Calgary P. M. Pexman, S. J. Lupker, and D. Jared (2001) reported longer response latencies in lexical decision tasks (LDTs) for homophones (e.g., maid) than for nonhomophones, and attributed this homophone effect to orthographic competition created by feedback activation from phonology. In the current study, two predictions of this feedback account were tested: (a) In LDT, observe homophone effects should be observed but not regularity or homograph effects because most exception words (e.g., pint) and homographs (e.g., wind) have different feedback characteristics than homophones do, and (b) in a phonological LDT (“does it sound like a word?”), regularity and homograph effects should be observed but not homophone effects. Both predictions were confirmed. These results support the claim that feedback activation from phonology plays a significant role in visual word recognition. The role of phonology in visual word recognition has long been In a recent investigation of the role of phonology in visual word an important issue in psycholinguistic research. A considerable recognition, Pexman, Lupker, and Jared (2001) examined homo- amount of research evidence supports the idea that phonology is phone effects in lexical decision tasks (LDTs). Homophones are activated early in the word recognition process (e.g., Berent & words like maid and made, where a single pronunciation maps Perfetti, 1995; Lukatela & Turvey, 2000; Perfetti & Bell, 1991), onto at least two spellings (and two meanings). -

Andra Kalnača a Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar

Andra Kalnača A Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar Andra Kalnača A Typological Perspective on Latvian Grammar Managing Editor: Anna Borowska Associate Editor: Helle Metslang Language Editor: Uldis Balodis Published by De Gruyter Open Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Munich/Boston This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 license, which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. Copyright © 2014 Andra Kalnača ISBN 978-3-11-041130-0 e- ISBN 978-3-11-041131-7 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Managing Editor: Anna Borowska Associate Editor: Helle Metslang Language Editor: Uldis Balodis www.degruyteropen.com Cover illustration: © Ieva Kalnača Contents Abbreviations I Introduction II 1 The Paradigmatics and Declension of Nouns 1 1.1 Introductory Remarks on Paradigmatics 1 1.2 Declension 4 1.2.1 Noun Forms and Palatalization 9 1.2.2 Nondeclinable Nouns 11 1.3 Case Syncretism 14 1.3.1 Instrumental 18 1.3.2 Vocative 25 1.4 Reflexive Nouns 34 1.5 Case Polyfunctionality and Case Alternation 47 1.6 Gender 66 2 The Paradigmatics and Conjugation of Verbs 74 2.1 Introductory Remarks 74 2.2 Conjugation 75 2.3 Tense 80 2.4 Person 83 3 Aspect 89