Family-Memoirs – About Strategies of Creating Identity in Vienna of the 1940S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mitteilungen Aus Dem Brenner-Archiv Nr. 31/2012

Mitteilungen aus dem Brenner-Archiv Nr. 31/2012 innsbruck university press Johann Holzner, Anton Unterkircher: Brenner-Archiv, Universität Innsbruck Gedruckt mit Unterstützung des Dekanats der Philologisch-Kulturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Innsbruck, des Amtes der Tiroler Landesregierung (Kulturabteilung) und des Kulturamts der Stadt Innsbruck ISSN 1027-5649 Eigentümer: Brenner-Forum und Forschungsinstitut Brenner-Archiv Innsbruck 2012 Bestellungen sind zu richten an: Forschungsinstitut Brenner-Archiv Universität Innsbruck (Tel. +43 512 507-4501) A-6020 Innsbruck, Josef-Hirn-Str. 5 brenner-archiv.uibk.ac.at Druck: Steigerdruck, 6094 Axams, Lindenweg 37 Satz: Barbara Halder und Christoph Wild Layout und Design: Christoph Wild Nachdruck oder Vervielfältigung nur mit Genehmigung der Herausgeber gestattet. © innsbruck university press, 2012 Universität Innsbruck 1. Auflage Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Inhalt Editorial 5 Texte Anna Rottensteiner: Lithops 7 Michael Sallinger: Die Schiffsschraube: oder der Anker im Buchstaben Erinnerungen eines Fossils an seine österreichische Literatur in einem Absatz 19 Aufsätze Klaus Müller-Salget: Ein verdächtiges Subjekt? Der Dichter Heinrich von Kleist 27 Hans Weichselbaum: „Eine bleiche Maske mit drei Löchern“ Zu Georg Trakls Selbstporträt 37 Csilla Mihály: Fremdheit als ausgeblendete Identität Bemerkungen zu Kafkas ‚In der Strafkolonie‘ 45 Sabine Eschgfäller: Karikaturen von Eng? Anmerkungen zu neu entdeckten Zeichnungen aus der Olmützer Villa Müller 69 Eleonore De Felip: Interieurs unter -

The 100 Most Influential Philosophers of All Time 7 His Entire Existence in Those Terms

Published in 2010 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010. Copyright © 2010 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved. Rosen Educational Services materials copyright © 2010 Rosen Educational Services, LLC. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services. For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932. First Edition Britannica Educational Publishing Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition Brian Duignan: Senior Editor, Religion and Philosophy Rosen Educational Services Jeanne Nagle: Senior Editor Nelson Sa: Art Director Nicole Russo: Designer Introduction by Stephanie Watson Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The 100 most influential philosophers of all time / edited by Brian Duignan.—1st ed. p. cm.—(The Britannica guide to the world’s most influential people) “In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.” Includes Index. ISBN 978-1-61530-057-0 (eBook) 1. Philosophy. 2. Philosophers. I. Duignan, Brian. II. Title: One hundred most -

Bruno Walter (Ca

[To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky Yale University Press New Haven and London Frontispiece: Bruno Walter (ca. ). Courtesy of Österreichisches Theatermuseum. Copyright © by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections and of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Sonia L. Shannon Set in Bulmer type by The Composing Room of Michigan, Grand Rapids, Mich. Printed in the United States of America by R. R. Donnelley,Harrisonburg, Va. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ryding, Erik S., – Bruno Walter : a world elsewhere / by Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references, filmography,and indexes. ISBN --- (cloth : alk. paper) . Walter, Bruno, ‒. Conductors (Music)— Biography. I. Pechefsky,Rebecca. II. Title. ML.W R .Ј—dc [B] - A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. For Emily, Mary, and William In memoriam Rachel Kemper and Howard Pechefsky Contents Illustrations follow pages and Preface xi Acknowledgments xv Bruno Schlesinger Berlin, Cologne, Hamburg,– Kapellmeister Walter Breslau, Pressburg, Riga, Berlin,‒ -

Evolution of One-Handed Piano Compositions

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE Evolution of One-Handed Piano Compositions Ignat Drozdov, BS, Mark Kidd, PhD, Irvin M. Modlin, MD, PhD Electronic searches were performed to investigate the evolution of one-handed piano com- positions and one-handed music techniques, and to identify individuals responsible for the development of music meant for playing with one hand. Particularly, composers such as Liszt, Ravel, Scriabin, and Prokofiev established a new model in music by writing works to meet the demands of a variety of pianist-amputees that included Count Géza Zichy (1849– 1924), Paul Wittgenstein (1887–1961), and Siegfried Rapp (b. 1915). Zichy was the first to amplify the scope of the repertoire to improve the variety of one-handed music; Wittgenstein developed and adapted specific and novel performance techniques to accommodate one- handedness; and Rapp sought to promote the stature of one-handed pianists among a musically sophisticated public able to appreciate the nuances of such maestros. (J Hand Surg 2008;33A:780–786. Copyright © 2008 by the American Society for Surgery of the Hand. All rights reserved.) Key words Amputation, hand, history of surgery, music, piano. UCH HAS BEEN WRITTEN ABOUT the creativity of EVOLUTION OF THE PIANO: OF FINGERS AND composers and the skills of musicians, and KEYS Mspecial emphases have been placed on the Pianists are graced with a rich and remarkable history of mind and the vagaries of neurosis and even madness in their instrument, which encompasses more than 850 the process of composition. Little consideration has years of development and evolution.1 From the keyed been given to physical defects and their influence on monochord in 1157, to the clavichord (late Medieval), both music and its interpretation. -

Nomination Form International Memory of the World Register

Nomination form International Memory of the World Register Philosophical Nachlass of Ludwig Wittgenstein (Austria, Canada, Netherlands, UK) ID Code [2016-26] 1.0 Summary (max 200 words) The subject of this joint nomination is the complete philosophical Nachlass of Austrian-British philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) is today widely recognized as one of the most important philosophers of the 20th century. His philosophy was the essential impulse to what was later called the “linguistic turn” in modern philosophy, but even beyond philosophy had a deep impact to many branches of the humanities and even in the arts. His famous Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (written 1918, published1921), the only philosophical book he published during his lifetime, is one of the most influential philosophical books ever written. After a break of ten years - teaching as a primary school teacher and working as architect - Wittgenstein continued his philosophical work at the University of Cambridge and developed a new philosophy of ordinary language, which became one of the leading philosophical movements especially in the Anglo- American world. Wittgenstein was unable to realize his intention to publish his new ideas before his death in 1951. In 1953 his literary executors published the Philosophische Untersuchungen / Philosophical Investigations posthumously, which is seen as the magnum opus of his later philosophy and has become one of the most important books in the history of modern philosophy. Wittgenstein’s philosophical development from 1914 to the Tractatus and his continuous philosophical work from 1929 till the end of his life is documented in detail in his philosophical Nachlass. It was listed in a systematic and complete form in 1969 by Georg Henrik von Wright, his student and successor in his chair in Cambridge (“The Wittgenstein Papers” in: Philosophical Review Vol 78,4.1969, p 483-503). -

Wittgenstein's Vienna Our Aim Is, by Academic Standards, a Radical One : to Use Each of Our Four Topics As a Mirror in Which to Reflect and to Study All the Others

TOUCHSTONE Gustav Klimt, from Ver Sacrum Wittgenstein' s VIENNA Allan Janik and Stephen Toulmin TOUCHSTONE A Touchstone Book Published by Simon and Schuster Copyright ® 1973 by Allan Janik and Stephen Toulmin All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form A Touchstone Book Published by Simon and Schuster A Division of Gulf & Western Corporation Simon & Schuster Building Rockefeller Center 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, N.Y. 10020 TOUCHSTONE and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster ISBN o-671-2136()-1 ISBN o-671-21725-9Pbk. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 72-83932 Designed by Eve Metz Manufactured in the United States of America 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 The publishers wish to thank the following for permission to repro duce photographs: Bettmann Archives, Art Forum, du magazine, and the National Library of Austria. For permission to reproduce a portion of Arnold SchOnberg's Verklarte Nacht, our thanks to As sociated Music Publishers, Inc., New York, N.Y., copyright by Bel mont Music, Los Angeles, California. Contents PREFACE 9 1. Introduction: PROBLEMS AND METHODS 13 2. Habsburg Vienna: CITY OF PARADOXES 33 The Ambiguity of Viennese Life The Habsburg Hausmacht: Francis I The Cilli Affair Francis Joseph The Character of the Viennese Bourgeoisie The Home and Family Life-The Role of the Press The Position of Women-The Failure of Liberalism The Conditions of Working-Class Life : The Housing Problem Viktor Adler and Austrian Social Democracy Karl Lueger and the Christian Social Party Georg von Schonerer and the German Nationalist Party Theodor Herzl and Zionism The Redl Affair Arthur Schnitzler's Literary Diagnosis of the Viennese Malaise Suicide inVienna 3. -

Tolstoy's Religious Influence on Young Wittgenstein

duty to the town of Turnov in Galicia, and happened to come upon a bookshop which however seemed to contain nothing but Tolstoy’s Religious Influence on Young Wittgenstein picture postcards. However, he went inside and found that it contained just one book: Tolstoy on The Gospels. He bought it Kamen Lozev merely because there was no other. He read it and re-read it, and South-West University ‘Neofit Rilski’, Blagoevgrad thenceforth had it always with him, under fire and at all times.’’ ( [email protected] Bertrand Russell to Lady Ottoline, December 20, 1919) According to Klagge Wittgenstein’s ‘near-obsession’ with Abstract: The paper is an attempt to explain the tremendous Tolstoy’s book during his wartime service is well documented. influence which Tolstoy’s Gospel in Brief had on young (Klagge 2011: 10) He read the book in the first week of September Wittgenstein. Factors enabling the ‘religious conversion’ of and ever since always had it at his side; wfor him the book Wittgenstein are investigated together with the Tolstoyan themes became a “talisman” which protected his life. His fellow soldiers discussed in the Notebooks, 1914-16, and the ethico-religious nicknamed him “the one with the Gospel.” final part of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Wittgenstein left another strong evidence of the huge influence of Tolstoy’s Gospel on him. A year later in July 1915 Key words: Tolstoy, young Wittgenstein, Gospel in Brief, he received a letter from Ludwig von Ficker, one of the prospect rationality, religion. publishers of the Tractatus, in which Ficker was expressing doubts that he would hardly survive under the hardships at the front. -

Nicole L. Immler Das Familiengedächtnis Der Wittgensteins Zu Verführerischen Lesarten Von (Auto-)Biographischen Texten

Aus: Nicole L. Immler Das Familiengedächtnis der Wittgensteins Zu verführerischen Lesarten von (auto-)biographischen Texten April 2011, 398 Seiten, kart., 35,80 €, ISBN 978-3-8376-1813-6 Welche Rolle spielen die »Familienerinnerungen« von Ludwig Wittgensteins Schwester Hermine bei der Entwicklung des Wittgenstein’schen Familienge- dächtnisses? Nicole L. Immler untersucht die Biographieforschung zu Witt- genstein und bietet eine quellenkritische Analyse seiner autobiographischen Reflexionen und deren Verknüpfung mit seinen philosophischen Gedanken. Die Studie geht den Konstruktionsprinzipien von Erzählung, Erinnerung und Identität nach, zeigt die mitunter dramatischen Wechselwirkungen zwischen Autobiographie und Familiengedächtnis und die Verschränkungen von Tex- ten von bzw. über Ludwig Wittgenstein. Ein Buch über die Relevanz Wittgen- steins für die Kulturwissenschaft. Nicole L. Immler (Dr. phil.) arbeitet als Historikerin und Kulturwissenschaft- lerin an der Universität Utrecht sowie in Wien. Weitere Informationen und Bestellung unter: www.transcript-verlag.de/ts1813/ts1813.php © 2011 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Inhalt Einleitung | 9 Das Phänomen ‚Ludwig Wittgenstein‘ | 14 Die Quellen und die Fragestellung | 16 Das Familiengedächtnis: Ein kulturwissenschaftliches Untersuchungsfeld | 18 Die Rückkehr der Auto-/Biographie in die Wissenschaftsgeschichte | 21 Die Quellenkritik | 24 Dank | 28 LUDWIG WITTGENSTEIN: AUTO-/BIOGRAPHISCHES I. Ludwig Wittgenstein und seine Biograph(inn)en | 31 1. Hermine Wittgenstein: Skizze ‚Ludwig‘ aus den Familienerinnerungen | 31 2. Wittgenstein-Rezeptionen: Verführerische Lesarten? | 38 2.1 Die Psychologisierungen in den 1970er Jahren | 42 2.2 Die Neubewertung des Wiener Fin de Siècle | 44 2.3 Der Vergangenheits-Diskurs in den 1990er Jahren | 47 2.4 Der ganzheitliche Blick: Biographie, Philosophie und Edition | 51 2.5 Die Suche nach einer Kohärenz von Werk und Leben | 56 3. Die Herausforderungen der Biographieforschung | 59 II. -

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Wittgenstein Ludwig Wittgenstein, 1910 Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein (* 26. April 1889 Ludwig Wittgenstein als Kleinkind, 1890 in Wien;† 29. April 1951 in Cambridge) war ein österreichisch-britischer Philosoph. Er lieferte bedeutende Beiträge zur Philosophie der Logik, der Sprache und des Bewusstseins. Sei- ne beiden Hauptwerke Logisch-philosophische Ab- handlung (Tractatus logico-philosophicus 1921) und Philosophische Untersuchungen (1953, postum) wurden zu wichtigen Bezugspunkten zweier philosophi- scher Schulen, des Logischen Positivismus und der Analytischen Sprachphilosophie. 1 Leben und Werk Ludwig Wittgenstein als Kind, vorne rechts mit den Schwestern Wittgenstein entstammt der österreichischen, früh assi- Hermine, Helene, Margarete und Bruder Paul milierten jüdischen Industriellenfamilie Wittgenstein, de- ren Wurzeln in der deutschen Kleinstadt Laasphe im Wittgensteiner Land liegen. Er war das jüngste von acht zu einer der reichsten Familien der Wiener Gesellschaft Kindern des Großindustriellen Karl Wittgenstein und sei- der Jahrhundertwende. Der Vater war ein Förderer zeit- ner Ehefrau Leopoldine, die aus einer Prager jüdischen genössischer Künstler, die Mutter eine begabte Pianistin. Familie stammte (geb. Kalmus). Karl Wittgenstein ge- Im Palais Wittgenstein verkehrten musikalische Größen hörte zu den erfolgreichsten Stahl-Industriellen der späten wie Clara Schumann, Gustav Mahler, Johannes Brahms Donaumonarchie, und das Ehepaar Wittgenstein wurde und Richard Strauss. 1 2 1 LEBEN UND WERK ges, den er 1911 in Jena besuchte, nahm Wittgenstein ein Studium in Cambridge am Trinity College auf, wo er sich intensiv mit den Schriften Bertrand Russells be- schäftigte, insbesondere mit den Principia Mathematica. Sein Ziel war es, wie bei Gottlob Frege die mathemati- schen Axiome aus logischen Prinzipien abzuleiten. Rus- sell zeigte sich nach den ersten Begegnungen nicht beein- druckt von Wittgenstein: „Nach der Vorlesung kam ein hitziger Deutscher, um mit mir zu streiten […] Eigent- lich ist es reine Zeitverschwendung, mit ihm zu reden.“ (16. -

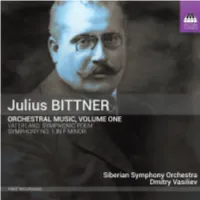

TOCC0500DIGIBKLT.Pdf

JULIUS BITTNER, FORGOTTEN ROMANTIC by Brendan G. Carroll Julius Bittner is one of music’s forgotten Romantics: his richly melodious works are never performed today and he is perhaps the last major composer of the early twentieth century to have been entirely ignored by the recording industry – until now: apart from four songs, this release marks the very first recording of any of his music in modern times. It reveals yet another colourful and individual voice among the many who came to prominence in the period before the First World War – and yet Bittner, an important and integral part of Viennese musical life before the Nazi Anschluss of 1938 subsumed Austria into the German Reich, was once one of the most frequently performed composers of contemporary opera in Austria. He wrote in a fluent, accessible and resolutely tonal style, with an undeniable melodic gift and a real flair for the stage. Bittner was born in Vienna on 9 April 1874, the same year as Franz Schmidt and Arnold Schoenberg. Both of his parents were musical, and he grew up in a cultured, middle-class home where artists and musicians were always welcomed (Brahms was a friend of the family). His father was a lawyer and later a distinguished judge, and initially young Julius followed his father into the legal profession, graduating with honours and eventually serving as a senior member of the judiciary throughout Lower Austria, until 1920. He subsequently became an important official in the Austrian Department of Justice, until ill health in the mid-1920s forced him to retire (he was diabetic). -

Realismus – Relativismus – Konstruktivismus

Realismus – Relativismus – Konstruktivismus Realism – Relativism – Constructivism Abstracts 38. Internationales Wittgenstein Symposium 9. – 15. August 2015 Kirchberg am Wechsel 38th International Wittgenstein Symposium August 9 – 15, 2015 Kirchberg am Wechsel Stand des Abstracta-Hefts: 25.07.2015 Aktuelle Änderungen unter: http://www.alws.at/abstract_2014.pdf. www.alws.at Book of abstracts publication date: 25/07/2015 For updates see: http://www.alws.at/abstract_2015.pdf. Distributors Die Österreichische Ludwig Wittgenstein Gesellschaft The Austrian Ludwig Wittgenstein Society Markt 63, A-2880 Kirchberg am Wechsel, Österreich / Austria Herausgeber: Christian Kanzian, Josef Mitterer, Katharina Neges Visuelle Gestaltung: Sascha Windholz Druck: Eigner-Druck, 3040 Neulengbach Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Abteilung Wissenschaft und Forschung (K3) des Amtes der NÖ Landesregierung ARE PHILOSOPHERS CONSTRUCTIVISTS OR „DIE FURCHT VOR DEM TODE IST DAS REALISTS IN THEIR ACTIONS? BESTE ZEICHEN EINES FALSCHEN, D.H. Krzysztof Abriszewski SCHLECHTEN LEBENS.“– LUDWIG Toruń, Poland WITTGENSTEINS SUCHE NACH DEM SINN DES LEBENS INMITTEN DES ERSTEN It is common to view realism and constructivism as WELTKRIEGS opposing positions. Less common, yet unsurprising, is drawing a continuum between the two poles. One can then Ulrich Arnswald locate any theoretical position on the poles or somewhere Karlsruhe, Deutschland in the middle, on the line. Actor-Network Theory added another, vertical axis of entity stabilization. What one can Ludwig Wittgenstein gezielt in den Kontext des großen ask is: “how can we measure this stabilization?” To answer Kriegs von 1914-1918 zu stellen, der sich seit dem letzten this question I use a model of four types of knowledge Jahr nun zum hundertsten Male jährt, ist äußerst reizvoll: production developed by Andrzej Zybertowicz Denn Wittgensteins Erleben dieses Kriegs, den wir heute (reproduction, discovery, redefinition, and design). -

GALA with SGT. PEPPER's LONELY

Richard Strauss’ tone poem depicts episodes from the literary masterpiece by Miguel Cervantes, with starring roles by the cello and viola. Join us for the odd adventures of Don Quixote and his “squire” Sancho Panza in a special chamber version by Hungarian cellist László Varga. With leading players of the Dallas Symphony Jolyon Pegis, cello and Alexander Kienle, horn. FRETS AND BOWS Sunday, April 14, 2019 at 3:00 pm Mount Vernon Music Hall Monday, April 15, 2019 at 7:30 pm First Baptist Church of GALA with SGT. PEPPER’S LONELY VIRTUOSO HORN DUO Farmers Branch BLUEGRASS BAND Saturday, November 3, 2018 at 7:30 pm 13017 William Dodson Pkwy, Saturday, August 25, 2018 at 7:00 pm Mount Vernon Music Hall Farmers Branch, TX 75234 Champagne and hors d’oeuvres 6:00 - 7:00 pm Sunday, November 4, 2018 at 3:00 pm Tuesday, April 16, 2019 AT 7:30 pm The Loft at ML Edwards Co. J. Erik Jonsson Public Library, 1515 Young St., Texas A&M University-Commerce (The Color of Sound) 103 S. Kaufman St., Mt. Vernon, TX 75457 Dallas, TX 75201 Admission: $50 Wednesday, November 14, 2018 at 7:30 pm Andrew Daniel, guitar *; Mark Miller and Texas A&M University-Commerce (The Color of Sound) Yuko Mansell, violin; Ute Miller, viola; This Bluegrass band was so good two years ago we just Zachary Mansell, cello; Mary Druhan, clarinet** had to bring them back! Don’t miss this Texas fab four Kerry Turner and Kristina Mascher Turner, horn, * (Mt. Vernon only), **(Commerce only) performing the Beatles’ best songs – made even better.