{PDF EPUB} a Woman's Civil War a Diary with Reminiscences Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations from the Revolution Through the Civil War General Editor: Kenneth M

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations from the Revolution through the Civil War General Editor: Kenneth M. Stampp Series M Selections from the Virginia Historical Society Part 6: Northern Virginia and Valley Associate Editor and Guide Compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 i Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Records of ante-bellum southern plantations from the Revolution through the Civil War [microform] Accompanied by printed reel guides, compiled by Martin Schipper. Contents: ser. A. Selections from the South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina (2 pts.)—[etc.]—ser. L. Selections from the Earl Gregg Swem Library, College of William and Mary—ser. M. Selections from the Virginia Historical Society. 1. Southern States—History—1775–1865—Sources. 2. Slave records—Southern States. 3. Plantation owners—Southern States—Archives. 4. Southern States— Genealogy. 5. Plantation life—Southern States— History—19th century—Sources. I. Stampp, Kenneth M. (Kenneth Milton) II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Schipper, Martin Paul. IV. South Caroliniana Library. V. South Carolina Historical Society. VI. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. VII. Maryland Historical Society. [F213] 975 86-892341 ISBN 1-55655-562-8 (microfilm : ser. M, pt. 6) Compilation © 1997 by Virginia Historical Society. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-562-8. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction........................................................................................................................... -

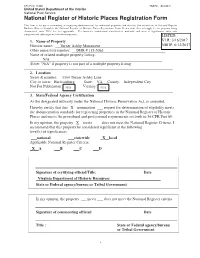

Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Turner Ashby Monument Other names/site number: DHR # 115-5063 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: 1164 Turner Ashby Lane City or town: Harrisonburg State: VA County: Independent City Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: N/A ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _X_ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: ___national ___statewide _X__local Applicable National Register Criteria: _X__A ___B ___C ___D Signature of certifying official/Title: Date _Virginia Department of Historic Resources__________________________ State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "NIA" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Winchester Historic District 2015 Boundary Increase Other names/site number: _V_D_HR_#____ 1 ___38 __ - __0_04_2 ________________ _ Name of related multiple property listing: NIA (Enter "NIA" if property is not part of a multiple property listing 2. Location Street & number: Amherst, Boscawen, Gerrard, Pall Mall, Stewart, and other streets City or town: Winchester State: Virginia County: Independent City Not For Publication: EJ Vicinity: ~ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this ....L nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ~ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: _national _statewide ..!..,local Applicable National Register Criteria: _!_A ..!..,B _!_C _D Date Virginia Department of Historic Resources State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property _meets_ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

The Aftermath of Sorrow: White Womenâ•Žs Search for Their Lost Cause, 1861-1917

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 The Aftermath of Sorrow: White Women's Search for Their Lost Cause, 1861 1917 Karen Aviva Rubin Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE AFTERMATH OF SORROW: WHITE WOMEN’S SEARCH FOR THEIR LOST CAUSE, 1861 – 1917 By KAREN AVIVA RUBIN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Karen A. Rubin defended on June 11, 2007. ______________________________ Elna C. Green Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Bruce Bickley Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Suzanne Sinke Committee Member ______________________________ Jonathan Grant Committee Member ______________________________ Valerie Jean Conner Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am pleased to have the opportunity to thank those who have given so generously of their time and expertise. I am particularly grateful for the time of the library staff at the Howard- Tilton Memorial Library at Tulane University, the Louisiana State University Manuscript Department, Kelly Wooten at the Perkins Library at Duke University, and especially Frances Pollard at the Virginia Historical Society, and Tim West, Curator of Manuscripts and Director of the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. I was fortunate to receive a Virginia Historical Society Mellon Fellowship as well as an Atlantic Coast Conference Traveling Research Grant to the Southern Historical Collection. -

Descendants of William Peake

Descendants of William Peake Generation 1 1. WILLIAM 1PEAKE1 was born before 1688 in of Prince William County, Virginia2. He died between Jan 11-Feb 17, 1761 in Bradley, Fairfax, Virginia3. He married Elizabeth Arrington, daughter of Wansford Arrington, about 1716. She was born about 1698 in Fairfax, Virginia, USA (Truro Parish). William Peake and Elizabeth Arrington had the following children: 2. i. MARY 2PEAKE1 was born between 1723-1729 in Overwhaton parish, Stafford County, VA. She died after 1763 in Fairfax, Virginia, USA. She married Abednego Adams, son of Francis Adams and Mary Godfrey, on Dec 17, 1746 in Fairfax, Virginia, USA. He was born in 1721 in Charles, Maryland, USA1. He died on Nov 01, 1809 in Fairfax, Virginia, USA1. 3. ii. HUMPHREY PEAKE SR.1 was born on Jan 13, 1732 in Prince William, Virginia, USA2, 4. He died on Jan 11, 1785 in Fairfax, Virginia, USA5-6. He married Mary Stonestreet, daughter of Butler Stonestreet and Frances Tolson, about 1755. She was born in 1738 in Battersea, Prince George's, Maryland2. She died on Nov 21, 1805 in Fairfax, Virginia, USA6. iii. WILLIAM PEAKE JR.. He died in 1756 in Fairfax, Virginia, USA. iv. HENRY PEAKE. 4. v. JOHN PEAKE7 was born about 1720 in Virginia, USA7. He married Mary Harrison, daughter of William Harrison and Sarah Hawley, about 1746 in Virginia, USA7. She was born after 1714 in Virginia, USA. She died after 1767 in Virginia, USA. Generation 2 2. MARY 2PEAKE (William 1)1 was born between 1723-1729 in Overwhaton parish, Stafford County, VA. -

Special Issue, 2008 Gathering of Clan Ewing

Journal of Clan Ewing SPECIAL ISSUE 2008 Gathering of Clan Ewing Winchester, Virginia September 18-21, 2008 Published by: Clan Ewing in America www.ClanEwing.org Clan Ewing in America 17721 Road 123 Cecil, Ohio 45821 www.ClanEwing.org CHANCELLOR David Neal Ewing DavidEwing93 at gmail dot com PAST CHANCELLORS 2004 - 2006 George William Ewing GeoEwing at aol dot com 1998 - 2004 Joseph Neff Ewing Jr. JoeNEwing at aol dot com 1995 - 1998 Margaret Ewing Fife 1993 - 1995 Rev. Ellsworth Samuel Ewing OFFICERS Chair Treasurer Secretary Mary Ewing Gosline Jane Ewing Weippert Eleanor Ewing Swineford Mary at Gosline dot net ClanEwing at verizon dot net louruton at futura dot net BOARD OF DIRECTORS David Neal Ewing George William Ewing Joseph Neff Ewing Jr. DavidEwing93 at gmail dot com GeoEwing at aol dot com JoeNEwing at aol dot com Mary Ewing Gosline Robert Hunter Johnson Mary at Gosline dot net ClanEwing at verizon dot net James R. McMichael William Ewing Riddle Jill Ewing Spitler JimMcMcl at gmail dot com Riddle at WmERiddle dot com JEwingSpit at aol dot com Eleanor Ewing Swineford Beth Ewing Toscos louruton at futura dot net 1lyngarden at verizon dot net ACTIVITY COORDINATORS Archivist Genealogist Journal Editor Betty Ewing Whitmer James R. McMichael William Ewing Riddle AirReservations at hotmail dot com JimMcMcl at gmail dot com Riddle at WmERiddle dot com Membership Merchandise Web Master Jill Ewing Spitler John C. Ewin William Ewing Riddle JEwingSpit at aol dot com JCEwin2004 at yahoo dot com Riddle at WmERiddle dot com Journal of Clan Ewing Special Issue 2008 Gathering September 2008 Published by: Clan Ewing in America, 17721 Road 123, Cecil, Ohio 45821. -

Shenandoah at WAR

Shenandoah AT WAR If this Valley is lost, Virginia– Gen. is Thomas lost! J. “Stonewall” Jackson One story... a thousand voices. Visitors Guide to the Shenandoah Valley’s Civil War Story Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District Explore the National Historic District Other Areas By degrees the whole line was thrown into confusion and I had no other recourse but to rally the Brigade on higher area by area... including Harpers Ferry, ground... There we took a stand and for hours successfully repulsed By degrees the whole line was Martinsburg, and thrown into confusion and I had no other recourse but to rally the Brigade on higher ground... There we took a stand and Winchester Charles Town Harpers Ferry including areas of Frederick and Clarke counties Page 40 for hours successfully repulsed Page 20 Third Winchester Signal Knob Winchester Battlefield Park including Middletown, Strasburg, and Front Royal By degrees the whole line was thrown into confusion and I had no other recourse but to rally the Page 24 Brigade on higher ground... There we took a stand and for hours successfully repulsed By degrees the whole line was thrown into confusion and I had no other recourse but to rally the Brigade on higher ground... There we took New Market including Luray and areas of Page County a stand and for hours successfully repulsed By degrees the whole line was thrown into confusion and I had no Page 28 other recourse but to rally the Brigade on higher ground... There we took a stand and for hours successfully repulsed By degrees the whole line was thrown into confusion and I had no other recourse but to rally the Brigade on higher Rockingham ground.. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Quality Of

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Aitx>r MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 "THE DEBATABLE LAND"; LOUDOUN AND FAUQUIER COUNTIES, VIRGINIA, DURING THE CIVIL WAR ERA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michael Stuart Mangus, B.A., M.A. -

W Inchester Occupied Winchester

SECOND WINCHESTER Winchester THIRD WINCHESTER FIRST WINCHESTER SECOND KERNSTOWN COOL SPRING FIRST KERNSTOWN CEDAR CREEK & BELLE GROVE CEDAR CREEK NATIONAL HISTORIC PARK Fighting commenced quite early this FISHER’S HILL Strasburg TOM’S BROOKE FRONT ROYAL Front Royal morning and cannonading has been going NEW MARKET BATTLEFIELD STATE HISTORICAL PARK NEW MARKET Luray on all day to the east of us on the Berryville New Market Road, but a mile or two from town... Harrisonburg Elkton Monterey CROSS KEYS McDowell PORT REPUBLIC MCDOWELL PIEDMONT Staunton Waynesboro inchester is in the northern, or lower, Shenandoah Valley. through the county courthouse, where their graffiti is still visible. The Formed by the Appalachians to the west and the Blue Ridge courthouse is now a museum open to the public, as is the house that Occupied Wto the east, the Valley shelters the Shenandoah River on its served as Stonewall Jackson’s Headquarters the winter before his famous journey down to the Potomac at Harpers Ferry. 1862 Valley Campaign. Throughout the region, historic farms, homes, mills, and cemeteries, along with outstanding museums and interpreted The Valley’s natural corridor formed by the river also spawned the 19th Winchester sites, all help tell the powerful history and moving legacy of the war. century Valley Pike (modern-day US 11), along which both commerce and armies traveled. In contemporary times, Interstate 81 has Visitors can walk the battlefields at Kernstown, Cool Spring, and Second replaced the Pike as the principal transportation route, bringing both and Third Winchester and learn how Jackson, Robert E. Lee, Jubal Early, opportunities and challenges to the interpretation of Civil War history. -

Virginia's Civil

Virginia’s Civil War A Guide to Manuscripts at the Virginia Historical Society A A., Jim, Letters, 1864. 2 items. Photocopies. Mss2A1b. This collection contains photocopies of two letters home from a member of the 30th Virginia Infantry Regiment. The first letter, 11 April 1864, concerns camp life near Kinston, N.C., and an impending advance of a Confederate ironclad on the Neuse River against New Bern, N.C. The second letter, 11 June 1864, includes family news, a description of life in the trenches on Turkey Hill in Henrico County during the battle of Cold Harbor, and speculation on Ulysses S. Grant's strategy. The collection includes typescript copies of both letters. Aaron, David, Letter, 1864. 1 item. Mss2AA753a1. A letter, 10 November 1864, from David Aaron to Dr. Thomas H. Williams of the Confederate Medical Department concerning Durant da Ponte, a reporter from the Richmond Whig, and medical supplies received by the CSS Stonewall. Albright, James W., Diary, 1862–1865. 1 item. Printed copy. Mss5:1AL155:1. Kept by James W. Albright of the 12th Virginia Artillery Battalion, this diary, 26 June 1862–9 April 1865, contains entries concerning the unit's service in the Seven Days' battles, the Suffolk and Petersburg campaigns, and the Appomattox campaign. The diary was printed in the Asheville Gazette News, 29 August 1908. Alexander, Thomas R., Account Book, 1848–1887. 1 volume. Mss5:3AL276:1. Kept by Thomas R. Alexander (d. 1866?), a Prince William County merchant, this account book, 1848–1887, contains a list, 1862, of merchandise confiscated by an unidentified Union cavalry regiment and the 49th New York Infantry Regiment of the Army of the Potomac. -

Our Speakers and Guides Peter Cozzens Is One of the Nation's Stephen Lang Is an Award Winning Actor George Rabbai Is a Music Professor and Leading Military Historians

Our Speakers and Guides Peter Cozzens is one of the nation's Stephen Lang is an award winning actor George Rabbai is a music professor and leading military historians. He is the who has played numerous historical professional jazz trumpet player. He has Ted Alexander is the founder and host of author of sixteen critically acclaimed books characters in movies. Among them; backed up notables such as Rosemary Chambersburg Civil War Seminars. He is a on the American Civil War and the Indian General George Pickett in “Gettysburg” Clooney and has performed with the popular author, tour guide and lecturer. Wars of the American West. All of Cozzens' and “Stonewall” Jackson in “Gods and Woody Herman band. His program on Civil books have been selections of the Book of Generals”. He has been a guest speaker at War bugle calls is always well received at Bevin Alexander is the author of ten the Month Club, History Book Club, and/or one of our seminars a few years ago and our seminars. books on military history, including How the Military Book Club. Cozzens’ This plans to attend schedule permitting. Wars Are Won, How America Got It Right, Terrible Sound: The Battle of John Schildt is the author of more than 20 and his latest book, How the South Could Chickamauga and The Shipwreck of Their Steve Longenecker is Professor of books on various aspects of the Civil War. Have Won the Civil War. His Lost Hopes: The Battles for Chattanooga were History at Bridgewater College. He is the Among them Jackson and the Preachers. -

Recollections of My Life, As I Can Now Recall Them

Volume I [Unnumbered page with the text centered] “Les Souvenirs de viellards sont une part d’heritage qu’ils doivent acquitter de leur vivants.” [The memories of old men are a part of their inheritance that they have to use up during their lifetime.] “Chè suole a riguardar giovare altrui” Purg: IV. 54 [“what joy—to look back at a path we’ve climbed! Dante Alighieri, Purgatorio IV.54 Allen Mandelbaum translator.] [Unnumbered page Opposite page 1 photo with signature and date below] R.T.W.Duke Jr,. Octo 23d 1899 [I 1] November 20th l899 It is my purpose, in this book, to jot down the recollections of my life, as I can now recall them. There will be little to interest any one but my children and possibly their children: So I shall write with no attempt at display or fine writing. May they who read profit by any errors I exhibit— Life has been very sweet and happy to me, because uneventful—and because no man ever had a better Father & Mother—Sister or Brother—truer friends, or a better, dearer, truer wife. My children are too young yet to judge what they will be to me. So far they have been as sweet and good as children of their ages could be. May they never in after years cause me any more sorrow than they have to this time. [I 2] [Centered on page] * On this same table—in my parlour on Octo 31st & Nov 1st, 1900—lay my dear little boy Edwin Ellicott—my little angel boy—embowered in flowers—the sweetest flower, that ever bloomed on earth—to flourish and fade not forever—in Heaven.