Turner Ashby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park 1 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

® 9 00 ebruary 2 F HARPERS FERRY NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK A Resource Assessment ® Center for State of the Parks ® More than a century ago, Congress established Yellowstone as the CONTENTS world’s first national park. That single act was the beginning of a remarkable and ongoing effort to protect this nation’s natural, historical, and cultural heritage. Today, Americans are learning that national park designation INTRODUCTION 1 alone cannot provide full resource protection. Many parks are compromised by development of adjacent lands, air and water pollu- KEY FINDINGS 6 tion, invasive plants and animals, and rapid increases in motorized recreation. Park officials often lack adequate information on the THE HARPERS FERRY status of and trends in conditions of critical resources. NATIONAL HISTORICAL The National Parks Conservation Association initiated the State of the Parks program in 2000 to assess the condition of natural and PARK ASSESSMENT 9 cultural resources in the parks, and determine how well equipped the CULTURAL RESOURCES— National Park Service is to protect the parks—its stewardship capac- NATION’S HISTORY ON DISPLAY ity. The goal is to provide information that will help policymakers, the public, and the National Park Service improve conditions in AT HARPERS FERRY 9 national parks, celebrate successes as models for other parks, and NATURAL RESOURCES— ensure a lasting legacy for future generations. PARK PROTECTS HISTORIC For more information about the methodology and research used in preparing this report and to learn more about the Center for State VIEWS AND RARE ANIMAL of the Parks, visit www.npca.org/stateoftheparks or contact: NPCA, AND PLANT SPECIES 18 Center for State of the Parks, P.O. -

Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations from the Revolution Through the Civil War General Editor: Kenneth M

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations from the Revolution through the Civil War General Editor: Kenneth M. Stampp Series M Selections from the Virginia Historical Society Part 6: Northern Virginia and Valley Associate Editor and Guide Compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 i Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Records of ante-bellum southern plantations from the Revolution through the Civil War [microform] Accompanied by printed reel guides, compiled by Martin Schipper. Contents: ser. A. Selections from the South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina (2 pts.)—[etc.]—ser. L. Selections from the Earl Gregg Swem Library, College of William and Mary—ser. M. Selections from the Virginia Historical Society. 1. Southern States—History—1775–1865—Sources. 2. Slave records—Southern States. 3. Plantation owners—Southern States—Archives. 4. Southern States— Genealogy. 5. Plantation life—Southern States— History—19th century—Sources. I. Stampp, Kenneth M. (Kenneth Milton) II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Schipper, Martin Paul. IV. South Caroliniana Library. V. South Carolina Historical Society. VI. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. VII. Maryland Historical Society. [F213] 975 86-892341 ISBN 1-55655-562-8 (microfilm : ser. M, pt. 6) Compilation © 1997 by Virginia Historical Society. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-562-8. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction........................................................................................................................... -

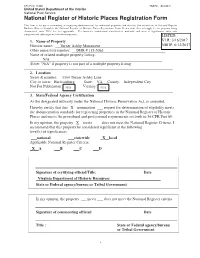

Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Turner Ashby Monument Other names/site number: DHR # 115-5063 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: 1164 Turner Ashby Lane City or town: Harrisonburg State: VA County: Independent City Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: N/A ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _X_ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: ___national ___statewide _X__local Applicable National Register Criteria: _X__A ___B ___C ___D Signature of certifying official/Title: Date _Virginia Department of Historic Resources__________________________ State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Shenandoah at WAR

Shenandoah AT WAR If this Valley is lost, Virginia– Gen. is Thomas lost! J. “Stonewall” Jackson One story... a thousand voices. Visitors Guide to the Shenandoah Valley’s Civil War Story Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District Explore the National Historic District Other Areas By degrees the whole line was thrown into confusion and I had no other recourse but to rally the Brigade on higher area by area... including Harpers Ferry, ground... There we took a stand and for hours successfully repulsed By degrees the whole line was Martinsburg, and thrown into confusion and I had no other recourse but to rally the Brigade on higher ground... There we took a stand and Winchester Charles Town Harpers Ferry including areas of Frederick and Clarke counties Page 40 for hours successfully repulsed Page 20 Third Winchester Signal Knob Winchester Battlefield Park including Middletown, Strasburg, and Front Royal By degrees the whole line was thrown into confusion and I had no other recourse but to rally the Page 24 Brigade on higher ground... There we took a stand and for hours successfully repulsed By degrees the whole line was thrown into confusion and I had no other recourse but to rally the Brigade on higher ground... There we took New Market including Luray and areas of Page County a stand and for hours successfully repulsed By degrees the whole line was thrown into confusion and I had no Page 28 other recourse but to rally the Brigade on higher ground... There we took a stand and for hours successfully repulsed By degrees the whole line was thrown into confusion and I had no other recourse but to rally the Brigade on higher Rockingham ground.. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Quality Of

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Aitx>r MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 "THE DEBATABLE LAND"; LOUDOUN AND FAUQUIER COUNTIES, VIRGINIA, DURING THE CIVIL WAR ERA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michael Stuart Mangus, B.A., M.A. -

W Inchester Occupied Winchester

SECOND WINCHESTER Winchester THIRD WINCHESTER FIRST WINCHESTER SECOND KERNSTOWN COOL SPRING FIRST KERNSTOWN CEDAR CREEK & BELLE GROVE CEDAR CREEK NATIONAL HISTORIC PARK Fighting commenced quite early this FISHER’S HILL Strasburg TOM’S BROOKE FRONT ROYAL Front Royal morning and cannonading has been going NEW MARKET BATTLEFIELD STATE HISTORICAL PARK NEW MARKET Luray on all day to the east of us on the Berryville New Market Road, but a mile or two from town... Harrisonburg Elkton Monterey CROSS KEYS McDowell PORT REPUBLIC MCDOWELL PIEDMONT Staunton Waynesboro inchester is in the northern, or lower, Shenandoah Valley. through the county courthouse, where their graffiti is still visible. The Formed by the Appalachians to the west and the Blue Ridge courthouse is now a museum open to the public, as is the house that Occupied Wto the east, the Valley shelters the Shenandoah River on its served as Stonewall Jackson’s Headquarters the winter before his famous journey down to the Potomac at Harpers Ferry. 1862 Valley Campaign. Throughout the region, historic farms, homes, mills, and cemeteries, along with outstanding museums and interpreted The Valley’s natural corridor formed by the river also spawned the 19th Winchester sites, all help tell the powerful history and moving legacy of the war. century Valley Pike (modern-day US 11), along which both commerce and armies traveled. In contemporary times, Interstate 81 has Visitors can walk the battlefields at Kernstown, Cool Spring, and Second replaced the Pike as the principal transportation route, bringing both and Third Winchester and learn how Jackson, Robert E. Lee, Jubal Early, opportunities and challenges to the interpretation of Civil War history. -

Virginia's Civil

Virginia’s Civil War A Guide to Manuscripts at the Virginia Historical Society A A., Jim, Letters, 1864. 2 items. Photocopies. Mss2A1b. This collection contains photocopies of two letters home from a member of the 30th Virginia Infantry Regiment. The first letter, 11 April 1864, concerns camp life near Kinston, N.C., and an impending advance of a Confederate ironclad on the Neuse River against New Bern, N.C. The second letter, 11 June 1864, includes family news, a description of life in the trenches on Turkey Hill in Henrico County during the battle of Cold Harbor, and speculation on Ulysses S. Grant's strategy. The collection includes typescript copies of both letters. Aaron, David, Letter, 1864. 1 item. Mss2AA753a1. A letter, 10 November 1864, from David Aaron to Dr. Thomas H. Williams of the Confederate Medical Department concerning Durant da Ponte, a reporter from the Richmond Whig, and medical supplies received by the CSS Stonewall. Albright, James W., Diary, 1862–1865. 1 item. Printed copy. Mss5:1AL155:1. Kept by James W. Albright of the 12th Virginia Artillery Battalion, this diary, 26 June 1862–9 April 1865, contains entries concerning the unit's service in the Seven Days' battles, the Suffolk and Petersburg campaigns, and the Appomattox campaign. The diary was printed in the Asheville Gazette News, 29 August 1908. Alexander, Thomas R., Account Book, 1848–1887. 1 volume. Mss5:3AL276:1. Kept by Thomas R. Alexander (d. 1866?), a Prince William County merchant, this account book, 1848–1887, contains a list, 1862, of merchandise confiscated by an unidentified Union cavalry regiment and the 49th New York Infantry Regiment of the Army of the Potomac. -

Our Speakers and Guides Peter Cozzens Is One of the Nation's Stephen Lang Is an Award Winning Actor George Rabbai Is a Music Professor and Leading Military Historians

Our Speakers and Guides Peter Cozzens is one of the nation's Stephen Lang is an award winning actor George Rabbai is a music professor and leading military historians. He is the who has played numerous historical professional jazz trumpet player. He has Ted Alexander is the founder and host of author of sixteen critically acclaimed books characters in movies. Among them; backed up notables such as Rosemary Chambersburg Civil War Seminars. He is a on the American Civil War and the Indian General George Pickett in “Gettysburg” Clooney and has performed with the popular author, tour guide and lecturer. Wars of the American West. All of Cozzens' and “Stonewall” Jackson in “Gods and Woody Herman band. His program on Civil books have been selections of the Book of Generals”. He has been a guest speaker at War bugle calls is always well received at Bevin Alexander is the author of ten the Month Club, History Book Club, and/or one of our seminars a few years ago and our seminars. books on military history, including How the Military Book Club. Cozzens’ This plans to attend schedule permitting. Wars Are Won, How America Got It Right, Terrible Sound: The Battle of John Schildt is the author of more than 20 and his latest book, How the South Could Chickamauga and The Shipwreck of Their Steve Longenecker is Professor of books on various aspects of the Civil War. Have Won the Civil War. His Lost Hopes: The Battles for Chattanooga were History at Bridgewater College. He is the Among them Jackson and the Preachers. -

Recollections of My Life, As I Can Now Recall Them

Volume I [Unnumbered page with the text centered] “Les Souvenirs de viellards sont une part d’heritage qu’ils doivent acquitter de leur vivants.” [The memories of old men are a part of their inheritance that they have to use up during their lifetime.] “Chè suole a riguardar giovare altrui” Purg: IV. 54 [“what joy—to look back at a path we’ve climbed! Dante Alighieri, Purgatorio IV.54 Allen Mandelbaum translator.] [Unnumbered page Opposite page 1 photo with signature and date below] R.T.W.Duke Jr,. Octo 23d 1899 [I 1] November 20th l899 It is my purpose, in this book, to jot down the recollections of my life, as I can now recall them. There will be little to interest any one but my children and possibly their children: So I shall write with no attempt at display or fine writing. May they who read profit by any errors I exhibit— Life has been very sweet and happy to me, because uneventful—and because no man ever had a better Father & Mother—Sister or Brother—truer friends, or a better, dearer, truer wife. My children are too young yet to judge what they will be to me. So far they have been as sweet and good as children of their ages could be. May they never in after years cause me any more sorrow than they have to this time. [I 2] [Centered on page] * On this same table—in my parlour on Octo 31st & Nov 1st, 1900—lay my dear little boy Edwin Ellicott—my little angel boy—embowered in flowers—the sweetest flower, that ever bloomed on earth—to flourish and fade not forever—in Heaven. -

Fauquier County, Virginia Tombstone Inscriptions, Volume 1 & 2

Fauquier County, Virginia Tombstone Inscriptions, Volume 1 & 2 http://innopac.fauquiercounty.gov/record=b1090877 Index courtesy of Fauquier County Public Library (http://fauquierlibrary.org) Last Name Maiden Name First Name Middle Name Volume Page(s) Notes ? Henry 2ndVol 84 ? Liza 2ndVol 83 ? Lottie M. 2ndVol 36 ? Masieth 2ndVol 153 child ? Antonia W. 1stVol 73 ? Bushrod J. 2ndVol 120 No last name ? Wines Elizabeth 1stVol 81 ? Elizabeth 1stVol 39 In Walker-Holmes Plot ? Horace 1stVol 76 1902 ? Lottie M 2ndVol 32 No last name ? Martha 2ndVol 105 Martha Carter? ? Pee Wee 1stVol 108 ? Will T 2ndVol 122 No last name Abel Ida A. 1stVol 124 Abel James Rodney 2ndVol 193 Abel Abell Neta F. 2ndVol 193 Abel Walter A. 2ndVol 193 Abelle Cora E. 2ndVol 130 Abelle Joseph P. 2ndVol 130 Abernathy Joseph H. 1stVol 35 Abernathy Wilbur Joe 2ndVol 36 Abrams Marion E. 1stVol 199 Abribat Tinsman Clarice 2ndVol 103 Abribat Mary Joseph 2ndVol 103 Acheson Jean C. 2ndVol 197 Action Lloyd P. 2ndVol 79 Action Louse A. 2ndVol 79 Louise? Adams Abner 1stVol 69 WWII Adams Abraham 1stVol 221 Adams Abraham 2ndVol 208 Adams Adaline H. 2ndVol 1 Adams Agnes Lee 2ndVol 25 Adams Alwylda 2ndVol 40 Adams Ann R. 2ndVol 25 Adams Anna R. 2ndVol 1 Adams Harrison Anna 2ndVol 25 Last Name Maiden Name First Name Middle Name Volume Page(s) Notes Adams Anna Mae 2ndVol 95 Adams Anne Alexander 1stVol 200 Adams Arthur Henry 2ndVol 114 III Adams Arthur Henry 2ndVol 114 Adams Bertha E. 2ndVol 25 Adams Bessie L. 1stVol 69 Adams Baron Bettie Kelly 2ndVol 122 Adams Carroll S. -

©2016 Ryan C. Bixby ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

©2016 Ryan C. Bixby ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “REFUSING TO JOIN THEIR WATERS AND MINGLE INTO ONE GRAND KINDRED STREAM”: THE TRANSFORMATION OF JEFFERSON COUNTY, WEST VIRGINIA IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Ryan C. Bixby August, 2016 “REFUSING TO JOIN THEIR WATERS AND MINGLE INTO ONE GRAND KINDRED STREAM”: THE TRANSFORMATION OF JEFFERSON COUNTY, WEST VIRGINIA IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA Ryan C. Bixby Dissertation Approved: Accepted: _________________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Department Chair Dr. Lesley J. Gordon Dr. Martin Wainwright _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Interim Dean of the College Dr. Gregory Wilson Dr. John C. Green _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Walter Hixson Dr. Chand Midha _________________________________ _________________________________ Committee Member Date Dr. Leonne Hudson _________________________________ Committee Member Dr. Ira D. Sasowsky ii ABSTRACT Encamped near Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, on September 15, 1861, Col. John White Geary of the 28th Pennsylvania Infantry wrote to his wife, Mary Church Henderson Geary. Geary described the majestic scene before him as the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers converged at a point before traveling toward the Chesapeake Bay. Sitting at the confluence of these two important waterways, -

Every Piece of Artillery, Every Wagon and Tent and Supporting Line of Troops Were in Easy Range of Our Vision

...every piece of artillery, every wagon and tent and supporting line of troops were in easy range of our vision. —Confederate Gen. John B. Gordon Observing from Signal Knob before the Battle of Cedar Creek October 1864 Signal Knob Area very close to succeeding in one of the largest battles west of the Blue Battlefields Ridge. The decisive Battle of Cedar Creek effectively ended the major Confederate war effort in the Shenandoah Valley. Front Royal May 23, 1862 Today, the road networks are much the same, and vestiges of these Jackson’s Valley Campaign military events have survived sufficiently to allow modern visitors to Fisher’s Hill retrace these famous campaigns. September 22, 1864 Sheridan’s Shenandoah Campaign Front Royal and the Cedar Creek battlefield each have visitor facilities Tom’s Brook that help explain Civil War events, while Belle Grove Plantation can October 9, 1864 tell you about life in the antebellum era. With information provided at Sheridan’s Shenandoah Campaign these places about walking trails, driving tours, and interpretive signage, visitors can walk parts of these and other battlefields and explore the Cedar Creek October 19, 1864 sites that tell this part of the Shenandoah Valley’s Civil War story. Sheridan’s Shenandoah Campaign Self-guided Tours Free printed driving tours of the Battle of Front Royal and the Battle of Fisher’s Hill are available at the visitor centers in this area and other Civil War sites. Walking tours of Front Royal and Strasburg are also available. A podcast tour of the Battle of Cedar Creek is available at nps.gov/cebe and at civilwartraveler.com/audio Go back quick and tell him that the Yankee Force is very small, one regiment of Maryland infantry...Tell him I know, for I went through the camps and got it out of an officer.