Recollections of My Life, As I Can Now Recall Them

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Troop Life, Into the the Municipal Building Will Be Ac- Annual Benefit Bridge and Fashion Out-Of-Doors This Summer

THE WESTFIELD LEADER THE LEADING AND MOST WIDELY CIRCULATED WEEKLY NEWSPAPER IN UNION COUNTY Y-FIFTH YEAR—No. 39 Published WESTFIELD, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, JUNE 9, 1955 Bverjr Thurnda.7 36 Page*—* Caat* iccalaureate Service In Girl Scouts Plan Nation-wide Air •esbyterian Church Summer Outdoor Raid Alert Set Anti-Polio Shots Camping Activities For Wednesday High School Senior Auxiliary Gives To Begin Tuesday f 3,500 to C. C. Home Three Day Camps Citizens Asked To ss of 1955 Scheduled: Season Take Shelter Until A donation of $3,500 to the Chil- Opens June 20 All Clear Siren Vaccine Arrives dren's Country Home, Mountain- ethodist Minister side, was made by the Senior Aux- Westfield Local Council Girl A nation-wide Civil Defense ex- From Eli Lilly o Give Address iliary to the home at a luncheon Scouts are making plans for camp- ercise will take place between meeting Tuesday at the Echo Lake ing activities which will enable noon, June 15 and 1 p.m. June 16. Country Club. The contribution Girl Scouts to carry scouting, as Westfield's staff headquarters in annual baccalaureate ser- represented the proceeds from the May Be Too late or the graduating class of practiced in troop life, into the the Municipal Building will be ac- annual benefit bridge and fashion out-of-doors this summer. Mrs. J. tivated in a support role between For Two Injection* • eld Senior High School will show held recently under the chair- i in the Presbyterian Church T. McAllister, executive director 6 p.m. and 11 p.m. -

Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations from the Revolution Through the Civil War General Editor: Kenneth M

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations from the Revolution through the Civil War General Editor: Kenneth M. Stampp Series M Selections from the Virginia Historical Society Part 6: Northern Virginia and Valley Associate Editor and Guide Compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 i Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Records of ante-bellum southern plantations from the Revolution through the Civil War [microform] Accompanied by printed reel guides, compiled by Martin Schipper. Contents: ser. A. Selections from the South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina (2 pts.)—[etc.]—ser. L. Selections from the Earl Gregg Swem Library, College of William and Mary—ser. M. Selections from the Virginia Historical Society. 1. Southern States—History—1775–1865—Sources. 2. Slave records—Southern States. 3. Plantation owners—Southern States—Archives. 4. Southern States— Genealogy. 5. Plantation life—Southern States— History—19th century—Sources. I. Stampp, Kenneth M. (Kenneth Milton) II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Schipper, Martin Paul. IV. South Caroliniana Library. V. South Carolina Historical Society. VI. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. VII. Maryland Historical Society. [F213] 975 86-892341 ISBN 1-55655-562-8 (microfilm : ser. M, pt. 6) Compilation © 1997 by Virginia Historical Society. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-562-8. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction........................................................................................................................... -

Negroes and Their Treatment In- Virginia from 1865 to 1867

NEGROES AND THEIR TREATMENT IN- VIRGINIA FROM 1865 TO 1867 A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the University of Virginia as a Part of the Work for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy BY JOHN PRESTON MCCONNELL. M. A. s! Prinud by B. D. SMITH 8L BROTHERS, Pulaski, Va. UVa H. Va. Doctoral Dissertation 3Q ' 'i...‘f3’:f'3*-‘.'3€J Lew‘ “(5&0 I COPYRIGHT 1910 BY J. P. MCCONNELL “Twat.“ TABLE OF CONTENTS. CHAPTER 1. NUMBER AND DISTRIBUTION OF NEGROES IN VIRGINIA. CHAPTER II. PUBLIC OPINION IN VIRGINIA IN REGARD TO EMANGIPATION. CHAPTER III. Tm: EFFECT or EMANCIPATION ON THE NEGROES. CHAPTER IV. , DISTURBING FORCES. CHAPTER V. THE EVOLUTION OF A SYSTEM OF HIRED LABOR. CHAPTER VI. - VAGRANCY AND VAGRLNCY LAWS. CHAPTER VII. CONTRACT LAWS. CHAPTER VIII. Tm: SLAVE CODE REPEALRD. CHAPTER IX. OUTRAGES ON FREEDMEN AND THE CIVIL COURTS FROM 1865 To 1867. CHAPTER X. FRRRDMRN AND CIVIL RIGHTS IN 1865 AND 1866. CHAPTER XI. ENFRANGHISEMENT 01» THE FREEDMEN. <. ”Anhthn; CHAPTER XII. EDUCATICN OE FREEDMEN. CHAPTER XIII. APPRENTICE LAWS. CHAPTER XIV. NEGRo MARRIAGE-s. CHAPTER XV. INSURRECTICN. CHAPTER XVI. SEPARATE CHURCHES TOR NEGRCEE. CHAPTER XVII. EFFECTS OR THE RECONSTRUCTION ACTS. CHAPTER XVIII. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION. BIBLIOGRAPHY. Negroes and Their Treatment in Vir- ginia from 1865 to 1867. CHAPTER I. NUMBER AND DISTRIBUTION OF NEGROES IN VIRGINIA. I HE surrender of General Lee at Appomattox virtual- ly closed the War between the States. This contest had freed the negroes throughout the seceding States; but the future status of the freedmen had not yet been determined. In the spring of 1865 there were probably about half a million negroes in the State of Virginia—a number suffi- ciently large to prove a very disturbing factor amongst a white population of less than 700,000. -

A Political Profile of Alexander HH Stuart of Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1988 "The Great Unappreciated Man": A Political Profile of Alexander H H Stuart of Virginia Scott H. Harris College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Harris, Scott H., ""The Great Unappreciated Man": A Political Profile of Alexander H H Stuart of Virginia" (1988). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625475. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-tw6r-tv11 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "THE GREAT UNAPPRECIATED MAN:" POLITICAL PROFILE OF ALEXANDER H. H. STUART OF VIRGINIA A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Scott H. Harris 1 9 8 8 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts / .fi-rra i Scott Hampton Harris Approved, May, 1988 M. Boyd Coyper,yy Ludwell H./lohnson III [J i Douglas praith For my Mother and Father. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis could not have been written without the involvement of many people. I am indebted to my thesis advisor. -

East of the River Real Estate

20 - MANCHESTER HPJRALD. p’ri., Oct. 15, 1982 MARCH home Meet MMH's Cards win, dedicated 'worry' doc lead series 2- U&R CONSTRUCTION CO. p a g e 15 East of the River presents . page 10 ^ ... page 11 Real Estate Valley View Manchester, Conn. Priced To Qualify For Cold, cloudy THROUGH THE YEARS The CHFA Buyer. today, Sunday Saturday, Oct. 16, 1982 See our newest area of Custom — see page 2 Single copy 25q: home ownership has been the best homes on Warren Avenue In Vernon, HanrhpHtrr Ipralb investment a family can make ... off Tunnel Rd. Be ready for the next Issue of IT STILL IS C.H.F.A. Fixed rate mortgages. Choose your Individual home site, and your new home plan now. Don't wait, this type of financing will not last Pales long. Call us todayl Trust made Homes priced from $70,000 and up. U&R REALTY CO. riating ' 99 E. Center St., Manchester PWA issue 643-2692 By Raymond T. DeMeo blazed across the front of a broad side prepared by the International Robert D. Murdock, Realtor Herald Reporter again Association of Machinists District Whom do you trust, P ratt & 91, and handed out to P&WA hourly Whitney employees? employees at the gates of the com WARSAW, Poland (U Pl) — The company brass, that tells you pany’s four Connecticut plants at Street clashes erupted Friday for your union is using you to increase the start of Friday’s work day. the third straight day in the Krakow STRAND REAL ESTATE Take your time MANCHESTER — its own power? “ Dear Fellow Employee” is the suburb of Nowa Huta after riot “LOVELY ROOFED DECK” Or your union, that tells you com salutation of a letter signed by police used tear gas, stun grenades and drive by these homes.. -

Private Sector

The Memory Keeper's Daughter Kim Edwards PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R oRL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen's Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi — 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R oRL, England First published in the United States of America by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. 2005 Published in Penguin Books 2006 11 13 15 17 19 20 18 16 14 12 Copyright © Kim Edwards, 2005 All rights reserved publisher's note This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. ISBNo 14 30.3714 5 CIP data available Printed in the United States of America Designed by Carlo. Bolte • Set in Granjon Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

My Voice Is My Weapon: Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics Of

MY VOICE IS MY WEAPON MY VOICE IS MY WEAPON Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics of Palestinian Resistance David A. McDonald Duke University Press ✹ Durham and London ✹ 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Cover by Heather Hensley. Interior by Courtney Leigh Baker Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data McDonald, David A., 1976– My voice is my weapon : music, nationalism, and the poetics of Palestinian resistance / David A. McDonald. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5468-0 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5479-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Palestinian Arabs—Music—History and criticism. 2. Music—Political aspects—Israel. 3. Music—Political aspects—Gaza Strip. 4. Music—Political aspects—West Bank. i. Title. ml3754.5.m33 2013 780.89′9274—dc23 2013012813 For Seamus Patrick McDonald Illustrations viii Note on Transliterations xi Note on Accessing Performance Videos xiii Acknowledgments xvii introduction ✹ 1 chapter 1. Nationalism, Belonging, and the Performativity of Resistance ✹ 17 chapter 2. Poets, Singers, and Songs ✹ 34 Voices in the Resistance Movement (1917–1967) chapter 3. Al- Naksa and the Emergence of Political Song (1967–1987) ✹ 78 chapter 4. The First Intifada and the Generation of Stones (1987–2000) ✹ 116 chapter 5. Revivals and New Arrivals ✹ 144 The al- Aqsa Intifada (2000–2010) CONTENTS chapter 6. “My Songs Can Reach the Whole Nation” ✹ 163 Baladna and Protest Song in Jordan chapter 7. Imprisonment and Exile ✹ 199 Negotiating Power and Resistance in Palestinian Protest Song chapter 8. -

Reconstructing American Historical Cinema This Page Intentionally Left Blank RECONSTRUCTING American Historical Cinema

Reconstructing American Historical Cinema This page intentionally left blank RECONSTRUCTING American Historical Cinema From Cimarron to Citizen Kane J. E. Smyth THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2006 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 10 09 08 07 06 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smyth, J. E., 1977- Reconstructing American historical cinema : from Cimarron to Citizen Kane / J. E. Smyth. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8131-2406-3 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8131-2406-9 (alk. paper) 1. Historical films--United States--History and criticism. 2. Motion pictures and history. I. Title. PN1995.9.H5S57 2006 791.43’658--dc22 2006020064 This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials. Manufactured in the United States of America. Member of the Association of American University Presses For Evelyn M. Smyth and Peter B. Smyth and for K. H. and C. -

RUDOLPH VALENTINO January 1971

-,- -- - OF THE SON SHEIK . --· -- December 1970 -.. , (1926) starring • January 1971 RUDOLPH VALENTINO ... r w ith Vilma Banky, Agnes Ayres, George Fawcett, Kar l Dane • .. • • i 1--...- \1 0 -/1/, , <;1,,,,,/ u/ ~m 11, .. 12/IOJ,1/, 2/11.<. $41 !!X 'ifjl!/1/. , .....- ,,,1.-1' 1 .' ,, ,t / /11 , , . ... S',7.98 ,,20 /1/ ,. Jl',1,11. Ir 111, 2400-_t,' (, 7 //,s • $/1,!!.!!8 "World's .. , . largest selection of things to show" THE ~ EASTIN-PHELAN p, "" CORPORATION I ... .. See paee 7 for territ orial li m1la· 1;on·son Hal Roach Productions. DAVE PORT IOWA 52808 • £ CHAZY HOUSE (,_l928l_, SPOOK Sl'OO.FI:'\G <192 i ) Jean ( n ghf side of the t r acks) ,nvites t he Farina, Joe, Wheeze, and 1! 1 the Gang have a "Gang•: ( wrong side of the tr ack•) l o a party comedy here that 1\ ,deal for HallOWK'n being at her house. 6VI the Gang d~sn't know that a story of gr aveyard~ - c. nd a thriller-diller Papa has f tx cd the house for an April Fool's for all t ·me!t ~ Day party for his fr i ends. S 2~• ~·ar da,c 8rr,-- version, 400 -f eet on 2 • 810 303, Standord Smmt yers or J OO feet ? O 2 , v ozs • Reuulart, s11.9e, Sale reels, 14 ozs, Regularly S1 2 98 , Sale Pnce Sl0.99 , 6o 0 '11 Super 8 vrrs•OQ, dSO -fect,, 2-lb~ .• S l0.99 Regu a rly SlJ 98. Sale Pn ce I Sl2.99 425 -fect I :, Regularly" ~ - t S12 99 400lc0 t on 8 o 289 Standard 8mm ver<lon SO r Sate r eels lJ o,s-. -

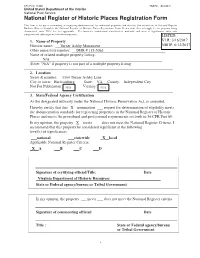

Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Turner Ashby Monument Other names/site number: DHR # 115-5063 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: 1164 Turner Ashby Lane City or town: Harrisonburg State: VA County: Independent City Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: N/A ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _X_ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: ___national ___statewide _X__local Applicable National Register Criteria: _X__A ___B ___C ___D Signature of certifying official/Title: Date _Virginia Department of Historic Resources__________________________ State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Alexander Moseley, Editor of the Richmond Whig Harrison Moseley Ethridge

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research Spring 1967 Alexander Moseley, editor of the Richmond Whig Harrison Moseley Ethridge Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Recommended Citation Ethridge, Harrison Moseley, "Alexander Moseley, editor of the Richmond Whig" (1967). Master's Theses. Paper 266. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALEXANDER MOSELEY, EDI'roR or THE RICHMOND WHIG A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Richmond In Partial Fulfillment of the Re~uirements tor the Degree Master of Arts by Harrison Mosley Ethridge May 1967 PREFACE The following pages are the study or a man, Alexander Moseley, and ot the newspaper with which he was intimately connected tor torty-tive years. There ue, admittedly gaps in the study. The period of Knov-Knoth ingism is omitted, tor example, because no substantial. material could be tound to shov his associations during the era. At other times, much more material could be found concerning Moseley's personal life than on his public lite. And, or course, otten it is difficult to prov~ that an edi torial opinion va.s necessarily his. Alexander Moseley's career was unique, however, in the great span ot history it covered. His association with :many of the events ot his time are shown in this pa.per, and aJ.so some of the personal lite ot a respected editor ot mid-nineteenth century Virginia. -

1868 the Memoirs of Israel Jefferson

1868 The Memoirs of Israel Jefferson Israel Jefferson, born in 1800, worked as a slave at Monticello. His parents, Edward and Jane Gillett, also served Jefferson as Monticello slaves. This memoir, assembled from Jefferson's interview with newspaperman S. F. Wetmore, was originally published in the Pike County Republican in December of 1873. I was born at Monticello, the seat of Thos. Jefferson, third President of the United States, December 25”—Christmas day in the morning. The year, I suppose was 1797. My earliest recollections are the exciting events attending the preparations of Mr. Jefferson and other members of his family on their removal to Washington D.C., where he was to take upon himself the responsibilities of the Executive of the United States for four years. My mother’s name was Jane. She was a slave of Thomas Jefferson’s and was born and always resided at Monticello till about five years after the death of Mr. Jefferson. She was sold, after his death, by the administrator, to a Mr. Joel Brown, and was taken to Charlottesville, where she died in 1837. She was the mother of thirteen children, all by one father, whose name was Edward Gillet. The children’s names were Barnaby, Edward, Priscilla, Agnes, Richard, James, Fanny, Lucy, Gilly, Israel, Moses, Susan, and Jane”— seven sons and six daughters. All these children, except myself, bore the surname of Gillett. The reason for my name being called Jefferson will appear in the proper place. After Mr. Jefferson had left his home to assume the duties of the office of President, all became quiet again in Monticello.