Reconstructing American Historical Cinema This Page Intentionally Left Blank RECONSTRUCTING American Historical Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Designation Lpb 559/08

REPORT ON DESIGNATION LPB 559/08 Name and Address of Property: MGM Building 2331 Second Avenue Legal Description: Lot 7 of Supplemental Plat to Block 27 to Bell and Denny’s First Addition to the City of Seattle, according to the plat thereof recorded in Volume 2 of Plats, Page 83, in King County, Washington; Except the northeasterly 12 feet thereof condemned for widening 2nd Avenue. At the public meeting held on October 1, 2008, the City of Seattle's Landmarks Preservation Board voted to approve designation of the MGM Building at 2331 Second Avenue, as a Seattle Landmark based upon satisfaction of the following standard for designation of SMC 25.12.350: C. It is associated in a significant way with a significant aspect of the cultural, political, or economic heritage of the community, City, state or nation; and D. It embodies the distinctive visible characteristics of an architectural style, period, or of a method of construction. STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE This building is notable both for its high degree of integrity and for its Art Deco style combining dramatic black terra cotta and yellowish brick. It is also one of the very few intact elements remaining on Seattle’s Film Row, a significant part of the Northwest’s economic and recreational life for nearly forty years. Neighborhood Context: The Development of Belltown Belltown may have seen more extensive changes than any other Seattle neighborhood, as most of its first incarnation was washed away in the early 20th century. The area now known as Belltown lies on the donation claim of William and Sarah Bell, who arrived with the Denny party at Alki Beach on November 13, 1851. -

Entertainment Industry, 1908-1980 Theme: Residential Properties Associated with the Entertainment Industry, 1908-1980

LOS ANGELES CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT Context: Entertainment Industry, 1908-1980 Theme: Residential Properties Associated with the Entertainment Industry, 1908-1980 Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources October 2017 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Entertainment Industry/Residential Properties Associated with the Entertainment Industry, 1908-1980 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 1 Contributors 1 Theme Introduction 1 Theme: Residential Properties Associated with the Entertainment Industry 3 Sub-theme: Residential Properties Associated with Significant Persons in the Entertainment Industry, 1908-1980 13 Sub-theme: Entertainment Industry Housing and Neighborhoods, 1908-1980 30 Selected Bibliography 52 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Entertainment Industry/Residential Properties Associated with the Entertainment Industry, 1908-1980 PREFACE This theme is a component of SurveyLA’s citywide historic context statement and provides guidance to field surveyors in identifying and evaluating potential historic resources relating to residential properties associated with the entertainment industry. Refer to www.HistoricPlacesLA.org for information on designated resources associated with this context (or themes) as well as those identified through SurveyLA and other surveys. CONTRIBUTORS The Entertainment Industry context (and all related themes) was prepared by Christine Lazzaretto and Heather Goers, Historic Resources Group, with significant guidance and input from Christy -

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

Come Into My Parlor. a Biography of the Aristocratic Everleigh Sisters of Chicago

COME INTO MY PARLOR Charles Washburn LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN IN MEMORY OF STEWART S. HOWE JOURNALISM CLASS OF 1928 STEWART S. HOWE FOUNDATION 176.5 W27c cop. 2 J.H.5. 4l/, oj> COME INTO MY PARLOR ^j* A BIOGRAPHY OF THE ARISTOCRATIC EVERLEIGH SISTERS OF CHICAGO By Charles Washburn Knickerbocker Publishing Co New York Copyright, 1934 NATIONAL LIBRARY PRESS PRINTED IN U.S.A. BY HUDSON OFFSET CO., INC.—N.Y.C. \a)21c~ contents Chapter Page Preface vii 1. The Upward Path . _ 11 II. The First Night 21 III. Papillons de la Nun 31 IV. Bath-House John and a First Ward Ball.... 43 V. The Sideshow 55 VI. The Big Top .... r 65 VII. The Prince and the Pauper 77 VIII. Murder in The Rue Dearborn 83 IX. Growing Pains 103 X. Those Nineties in Chicago 117 XL Big Jim Colosimo 133 XII. Tinsel and Glitter 145 XIII. Calumet 412 159 XIV. The "Perfessor" 167 XV. Night Press Rakes 173 XVI. From Bawd to Worse 181 XVII. The Forces Mobilize 187 XVIII. Handwriting on the Wall 193 XIX. The Last Night 201 XX. Wayman and the Final Raids 213 XXI. Exit Madams 241 Index 253 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My grateful appreciation to Lillian Roza, for checking dates John Kelley, for early Chicago history Ned Alvord, for data on brothels in general Tom Bourke Pauline Carson Palmer Wright Jack Lait The Chicago Public Library The New York Public Library and The Sisters Themselves TO JOHN CHAPMAN of The York Daily News WHO NEVER WAS IN ONE — PREFACE THE EVERLEIGH SISTERS, should the name lack a familiar ring, were definitely the most spectacular madams of the most spectacular bagnio which millionaires of the early- twentieth century supped and sported. -

Vaudeville Trails Thru the West"

Thm^\Afest CHOGomTfca3M^si^'reirifii ai*r Maiiw«MawtiB»ci>»«w iwMX»ww» cr i:i wmmms misssm mm mm »ck»: m^ (sam m ^i^^^ This Book is the Property of PEi^MYOcm^M.AGE :m:^y:^r^''''< .y^''^..^-*Ky '''<. ^i^^m^^^ BONES, "Mr. Interlocutor, can you tell me why Herbert Lloyd's Guide Book is like a tooth brush?" INTERL. "No, Mr, Bones, why is Herbert Lloyd's Guide Book like a tooth brush?" BONES, "Because everybody should have one of their own". Give this entire book the "Once Over" and acquaint yourself with the great variety of information it contains. Verify all Train Times. Patronize the Advertisers, who I PLEASE have made this book possible. Be "Matey" and boost the book. This Guide is fully copyrighted and its rights will be protected. Two other Guide Books now being compiled, cover- ing the balance of the country. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from Brigham Young University http://archive.org/details/vaudevilletrailsOOIIoy LIBRARY Brigham Young University AMERICANA PN 3 1197 23465 7887 — f Vauaeville Trails Thru tne ^iV^est *' By One vC^Jio Knows' M Copyrighted, 1919 by HERBERT LLOYD msiGimM wouNG<uNiveRSBtr UPb 1 HERBERT LLOYD'S VAUDEVILLE GUIDE GENERAL INDEX. Page Page Addresses 39 Muskogee 130-131 Advertiser's Index (follows this index) New Orleans 131 to 134 Advertising Rates... (On application) North Yakima 220 Calendar for 1919.... 30 Oakland ...135 to 137 Calendar for 1920 31 Ogden 138-139 Oklahoma City 140 to 142 CIRCUITS. Omaha 143 to 145 Ackerman Harris 19 & Portland 146 to 150 Interstate . -

Prostitutes, Feminists, and the War on White Slavery

Decades of Reform: Prostitutes, Feminists, and the War on White Slavery By: Jodie Masotta Under the direction of: Professor Nicole Phelps & Professor Major Jackson University of Vermont Undergraduate Honors Thesis College of Arts and Sciences, Honors College Department of History & Department of English April 2013 Introduction to Project: This research should be approached as an interdisciplinary project that combines the fields of history and English. The essay portion should be read first and be seen as a way to situate the poems in a historical setting. It is not merely an extensive introduction, however, and the argument that it makes is relevant to the poetry that comes afterward. In the historical introduction, I focus on the importance of allowing the prostitutes that lived in this time to have their own voice and represent themselves honestly, instead of losing sight of their desires and preferences in the political arguments that were made at the time. The poetry thus focuses on providing a creative and representational voice for these women. Historical poetry straddles the disciplines of history and English and “through the supremacy of figurative language and sonic echoes, the [historical] poem… remains fiercely loyal to the past while offering a kind of social function in which poetry becomes a ritualistic act of remembrance and imagining that goes beyond mere narration of history.”1 The creative portion of the project is a series of dramatic monologues, written through the voices of prostitutes that I have come to appreciate and understand as being different and individualized through my historical research The characters in these poems should be viewed as real life examples of women who willingly became prostitutes. -

Mervyn Leroy GOLD DIGGERS of 1933 (1933), 97 Min

January 30, 2018 (XXXVI:1) Mervyn LeRoy GOLD DIGGERS OF 1933 (1933), 97 min. (The online version of this handout has hot urls.) National Film Registry, 2003 Directed by Mervyn LeRoy Numbers created and directed by Busby Berkeley Writing by Erwin S. Gelsey & James Seymour, David Boehm & Ben Markson (dialogue), Avery Hopwood (based on a play by) Produced by Robert Lord, Jack L. Warner, Raymond Griffith (uncredited) Cinematography Sol Polito Film Editing George Amy Art Direction Anton Grot Costume Design Orry-Kelly Warren William…J. Lawrence Bradford him a major director. Some of the other 65 films he directed were Joan Blondell…Carol King Mary, Mary (1963), Gypsy (1962), The FBI Story (1959), No Aline MacMahon…Trixie Lorraine Time for Sergeants (1958), The Bad Seed (1956), Mister Roberts Ruby Keeler…Polly Parker (1955), Rose Marie (1954), Million Dollar Mermaid (1952), Quo Dick Powell…Brad Roberts Vadis? (1951), Any Number Can Play (1949), Little Women Guy Kibbee…Faneul H. Peabody (1949), The House I Live In (1945), Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo Ned Sparks…Barney Hopkins (1944), Madame Curie (1943), They Won't Forget (1937) [a Ginger Rogers…Fay Fortune great social issue film, also notable for the first sweatered film Billy Bart…The Baby appearance by his discovery Judy Turner, whose name he Etta Moten..soloist in “Remember My Forgotten Man” changed to Lana], I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932), and Two Seconds (1931). He produced 28 films, one of which MERVYN LE ROY (b. October 15, 1900 in San Francisco, was The Wizard of Oz (1939) hence the inscription on his CA—d. -

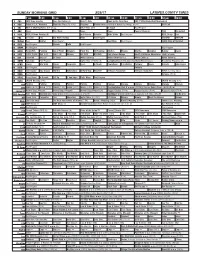

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/26/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 Am 7:30 8 Am 8:30 9 Am 9:30 10 Am 10:30 11 Am 11:30 12 Pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Best/C

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 3/26/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Best/C. Bsk. Road to the Final Four 2017 NCAA Basketball Tournament 4 NBC Today in L.A.: Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Pregame Hockey Minnesota Wild at Detroit Red Wings. (N) Å PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Special Olympics NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program NASCAR NASCAR 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program (500) Days of Summer 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Cooking Baking Sara’s 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Rick Steves-Europe Huell’s California Adventures: Huell & Louie 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch White Collar Å White Collar Wanted. White Collar Å White Collar Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho (N) La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Película Película 50 KOCE Odd Squad Odd Squad Martha Cyberchase Clifford-Dog WordGirl Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow NOVA Surviving Ebola. -

Vigee Le Brun's Memoirs

The Memoirs of Madame Vigee Le Brun Translated by Lionel Strachey 1903 Translation of : Souvenirs Originally published New York: Doubleday, Page CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 - YOUTH CHAPTER 2 - UP THE LADDER OF FAME CHAPTER 3 - WORK AND PLEASURE CHAPTER 4 - EXILE CHAPTER 5 - NEAPOLITAN DAYS CHAPTER 6 - TURIN AND VIENNA CHAPTER 7 - SAINT PETERSBURG CHAPTER 8 - LIFE IN RUSSIA CHAPTER 9 - CATHERINE II CHAPTER 10 - THE EMPEROR PAUL CHAPTER 11 - FAMILY AFFAIRS CHAPTER 12 - MOSCOW CHAPTER 13 - GOOD-BY TO RUSSIA CHAPTER 14 - HOMEWARD BOUND CHAPTER 15 - OLD FRIENDS AND NEW CHAPTER 16 - UNMERRY ENGLAND CHAPTER 17 - PERSONS AND PLACES IN BRITAIN CHAPTER 18 - BONAPARTES AND BOURBONS CHAPTER I - YOUTH PRECOCIOUS TALENTS MANIFESTED - MLLE. VIGEE'S FATHER AND MOTHER - DEATH OF HER FATHER - A FRIEND OF HER GIRLHOOD - HER MOTHER REMARRIES - MLLE. VIGEE'S FIRST PORTRAIT OF NOTE (COUNT SCHOUVALOFF) - ACQUAINTANCE WITH MME. GEOFFRIN - THE AUTHORESS'S PURITANICAL BRINGING-UP - MALE SITTERS ATTEMPT FLIRTATION - PUBLIC RESORTS OF PARIS BEFORE THE REVOLUTION. I will begin by speaking of my childhood, which is the symbol, so to say, of my whole life, since my love for painting declared itself in my earliest youth. I was sent to a boarding-school at the age of six, and remained there until I was eleven. During that time I scrawled on everything at all seasons; my copy-books, and even my schoolmates', I decorated with marginal drawings of heads, some full-face, others in profile; on the walls of the dormitory I drew faces and landscapes with coloured chalks. So it may easily be imagined how often I was condemned to bread and water. -

Universit Y of Oklahoma Press

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA PRESS NEW BOOKS SPRING/SUMMER 2019 Congratulations to our Recent Award Winners H BOBBIE AND JOHN NAU BOOK PRIZE H CORAL HORTON TULLIS MEMORIAL H RAY AND PAT BROWNE AWARD H AWARD FOR EXCELLENCE IN IN AMERICAN CIVIL WAR ERA HISTORY PRIZE FOR BEST BOOK ON TEXAS HISTORY BEST EDITED EDITION IN POPULAR U.S. ARMY HISTORY WRITING The John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History H KATE BROOCKS BATES AWARD CULTURE AND AMERICAN CULTURE Army Historical Foundation H A.M. PATE JR. AWARD IN FOR HISTORICAL RESEARCH Popular Culture Association/ CIVIL WAR HISTORY Texas State Historical Association American Culture Association EMORY UPTON Fort Worth Civil War Round Table H PRESIDIO LA BAHIA AWARD Misunderstood Reformer H SOUTHWEST BOOK AWARDS Sons of the Republic of Texas THE POPULAR FRONTIER By David Fitzpatrick Border Regional Library Association Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and $29.95s CLOTH ARREDONDO Transnational Mass Culture 978-0-8061-5720-7 CIVIL WAR IN THE SOUTHWEST Last Spanish Ruler of Texas and Edited by Frank Christianson BORDERLANDS, 1861–1867 Northeastern New Spain $32.95s CLOTH By Andrew E. Masich By Bradley Folsom 978-0-8061-5894-5 $26.95s PAPER $29.95 CLOTH 978-0-8061-6096-2 978-0-8061-5697-2 H CO-FOUNDERS BEST BOOK OF 2017 H THOMAS J. LYON AWARD H MERITORIOUS BOOK AWARD H FINE ART—GOLD MEDAL Westerners International BEST BOOK IN WESTERN AMERICAN Utah State Historical Society Independent Publisher Book Awards LITERARY AND CULTURAL STUDIES H THOMAS J. LYON AWARD 2018 EYEWITNESS TO THE FETTERMAN FIGHT BOTH SIDES OF THE BULLPEN BEST BOOK IN WESTERN AMERICAN Indian Views ERNEST HAYCOX AND THE WESTERN Navajo Trade and Posts LITERARY AND CULTURAL STUDIES Edited by John Monnett By Richard W. -

Julio Fernández

Biblioteca Pública de Alicante pág. 1 a 28 cine actual pág. 29 a 73 cine clásico pág. 74 a 83 cine infantil índice Biblioteca Pública de Alicante 1 Los abrazos rotos [DVD-Vídeo] / escrita y dirigida por Pedro Almodóvar ; una producción El Deseo, S.A., productor Agustín Almodóvar ; música Alberto Iglesias Madrid : El Deseo : Cameo, 2009. -- 2 DVD (ca. 125, 30 min.) : son., col. Int. : Penélope Cruz, Lluís Homar, Blanca Portillo, José Luis Gómez, Ruben Ochandiano, Tamar Novas Cine español. Drama España, 2009 Contiene: Disco 1: La película -- Disco 2: Extras No recomendada para menores de 18 años Sinopsis: Un hombre escribe, vive y ama en la oscuridad. Catorce años antes sufrió junto a Lena, la mujer de su vida, un brutal accidente de R.V. 8688 coche en la isla de Lanzarote que lo dejó ciego. En la actualidad, vive gracias a los guiones que escribe y a la ayuda de su antigua y fiel directora de producción, Judit García, y de Diego, el hijo de ésta, secretario, mecanógrafo y lazarillo. 2 Al otro lado [DVD-Vídeo] / guión y dirección Fatih Akin Barcelona : Cameo Media, D.L. 2008. -- 1 disco (DVD-Vídeo) (117 min.) : son., col. ; 12 cm Intérpretes: Tuncel Kurtiz, Nursel Köse, Patrycia Ziolkowska, Hanna Schygulla, Nurgül Yesilcay, Baki Davrak Melodrama Producción Alemania-Turquía-Italia, 2007 No recomendada para menores de 13 años Idiomas: alemán, castellano, inglés y turco; Subtít.: castellano y catalán Sinopsis: Las fragiles vidas de seis personas se cruzan durante sus viajes emocionales hacia el perdón y la reconciliación , entre Alemania y Turquía. R.V. -

PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - Hollywood 65 Auction 65, Auction Date: 10/17/2014

26662 Agoura Road, Calabasas, CA 91302 Tel: 310.859.7701 Fax: 310.859.3842 PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - Hollywood 65 Auction 65, Auction Date: 10/17/2014 LOT ITEM PRICE PREMIUM 1 AUTO RACING AND CLASSIC AUTOS IN FILM (14) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS. $350 2 SEX IN CINEMA (55) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS. $4,500 3 LILLIAN GISH VINTAGE PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPH BY HARTSOOK STUDIO. $200 4 COLLECTION OF (19) PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHS OF LUCILLE BALL, TALLULAH $325 BANKHEAD, THEDA BARA, JOAN CRAWFORD, AND OTHERS. 5 ANNA MAY WONG SIGNED PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPH BY CECIL BEATON. $4,000 6 MABEL NORMAND (7) SILENT-ERA VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS. $200 7 EARLY CHILD-STARS (11) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS INCLUDING OUR GANG AND $225 JACKIE COOGAN. 9 BARBARA LA MARR (3) VINTAGE PHOTOS INCLUDING ONE ON HER DEATHBED. $325 10 ALLA NAZIMOVA (4) VINTAGE PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHS. $300 11 SILENT-FILM LEADING LADIES (13) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS. $200 13 SILENT-FILM LEADING MEN (10) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS. $200 14 PRE-CODE BLONDES (24) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS. $325 15 CHARLIE CHAPLIN AND PAULETTE GODDARD (2) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS. $350 16 COLLECTION OF (12) OVERSIZE PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHS OF RENÉE ADORÉE, $400 MARCELINE DAY, AND OTHERS. 17 COLLECTION OF (17) OVERSIZE PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHS OF EVELYN BRENT, $1,200 NANCY CARROLL, LILI DAMITA, MARLENE DIETRICH, MIRIAM HOPKINS, MARY PICKFORD, GINGER ROGERS, GLORIA SWANSON, FAY WRAY AND OTHERS. 18 MYRNA LOY (14) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS INCLUDING SEVERAL RARE $375 PRE-CODE IMAGES. Page 1 of 85 26662 Agoura Road, Calabasas, CA 91302 Tel: 310.859.7701 Fax: 310.859.3842 PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - Hollywood 65 Auction 65, Auction Date: 10/17/2014 LOT ITEM PRICE PREMIUM 19 PREMIUM SELECTION OF LEADING MEN (32) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS.