Dissertation Front Matter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 5, 2019 Press Release WINNERS of the 7TH ANNUAL

March 5, 2019 Press release WINNERS OF THE 7TH ANNUAL THE ART NEWSPAPER RUSSIA AWARD ANNOUNCED On March 1, the 7th Annual Award of The Art Newspaper Russia took place. 2018 winners in categories “Museum of the Year”, “Exhibition of the Year”, “Book of the Year”, “Restoration of the Year” and “Personal Contribution” were announced at the Gostiny Dvor. The annual award of The Art Newspaper Russia is one of the most anticipated events in the art world, an acknowledgment of outstanding achievements in the field. The award highlights the past year's most significant events in Russian art both in Russia and abroad, as well as the work of patrons of the art in developing and preserving cultural heritage. The choice of winners was determined by both public response and the professional community's feedback. The award itself is a sculpture by Russian artist Sergey Shekhovtsov depicting the Big Ben of London and the Spasskaya Tower of the Moscow Kremlin as intersecting clock hands. The Art Newspaper highlights the events that incorporate Russia into the international art scene, promote Russian art abroad and, on the other hand, allow Russians to see and appreciate the art of the world. Inna Bazhenova, publisher and founder of The Art Newspaper Russia Award, the head the Department of Culture of Moscow Alexander Kibovsky and the editor-in-chief of The Art Newspaper Russia Milena Orlova opened the ceremony. This year the jewellery company Mercury became the general partner of The Art Newspaper Russia Award. For Mercury, cooperation with the number one art newspaper was a continuation of the company’s strategy to support the most significant cultural events. -

KNIFER, MANGELOS, VANIŠTA September 8 – October 3, 2015 1018 Madison Avenue, New York Opening Reception: Tuesday, September 8, 6 – 8 Pm

KNIFER, MANGELOS, VANIŠTA September 8 – October 3, 2015 1018 Madison Avenue, New York Opening Reception: Tuesday, September 8, 6 – 8 pm NEW YORK, August 7, 2015 – Mitchell-Innes & Nash is pleased to present an exhibition of works by three of the founding members of the Gorgona Group: Julije Knifer, Mangelos and Josip Vaništa. The Gorgona Group – whose name references the monstrous, snake-haired creatures of classical Greek mythology – was a radical, Croatian art collective active in Zagreb from 1959 to 1966, which anticipated the Conceptual Art movement that emerged in several countries in Europe and America in the 1970s. Loosely organized and without a singular aesthetic ideology, the group was defined by the “gorgonic spirit,” which tended toward nihilism and „anti-art‟ concepts. The exhibition will take place in concurrence with MoMA‟s upcoming show, Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960 – 1980, and will feature a selection of paintings, works on paper and sculpture dating from 1947 to 1990 to be exhibited in the United States for the first time. The exhibition will be on view from September 8 through October 3, 2015 at 1018 Madison Avenue in New York. Julije Knifer was born in Osijek, Croatia in 1924 and died in Paris in 2004. While Knifer‟s work stems from the Russian school of Suprematist painters, his practice evolved towards an almost exclusive exploration of “the meander”: a geometric, maze-like form of Classical origins composed of intersecting horizontal and vertical lines. This motif appears in the second issue of Gorgona, the group‟s anti-review magazine, which was conceived by Knifer and designed so the pages produce an endless, meandering loop. -

View Sample Pages

CHINA RESEARCH MONOGRAPH 51 F M" INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES ~ '-J UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA • BERKELEY c::<::s CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES Cross-Cultural Readings of Chineseness Narratives, Images, and Interpretations of the 1990s EDITED BY Wen-hsin Yeh A publication of the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of Califor nia, Berkeley. Although the Institute of East Asian Studies is responsible for the selection and acceptance of manuscripts in this series, responsibil ity for the opinions expressed and for the accuracy of statements rests with their authors. Correspondence and manuscripts may be sent to: Ms. Joanne Sandstrom, Managing Editor Institute of East Asian Studies University of California Berkeley, California 94720-2318 E-mail: [email protected] The China Research Monograph series is one of several publications series sponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies in conjunction with its constituent units. The others include the Japan Research Monograph series, the Korea Research Monograph series, and the Research Papers and Policy Studies series. A list of recent publications appears at the back of the book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cross-cultural readings of Chineseness : narratives, images, and interpretations of the 1990s I edited by Wen-hsin Yeh. p. em. - (China research monograph; 51) Collection of papers presented at the conference "Theoretical Issues in Modern Chinese Literary and Cultural Studies". Includes bibliographical references ISBN 1-55729-064-4 1. Chinese literature-20th century-History and criticism Congresses. 2. Arts, Chinese-20th century Congresses. 3. Motion picture-History and criticism Congresses. 4. Postmodernism-China Congresses. I. Yeh, Wen-hsin. -

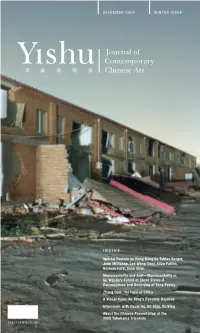

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE Special Feature on Hong Kong By

DECEMBER 2005 WINTER ISSUE INSIDE Special Feature on Hong Kong by Tobias Berger, John Millichap, Lee Weng Choy, Eliza Patten, Norman Ford, Sean Chen Monumentality and Anti—Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles-A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Zhang Dali: The Face of China A Visual Koan: Xu Bing's Dynamic Desktop Interviews with Oscar Ho, Uli Sigg, Xu Bing About the Chinese Presentation at the 2005 Yokohama Triennale US$12.00 NT$350.00 US$10.00 NT$350.00 Art & Collection Editor’s Note Contributors Hong Kong SAR: Special Art Region Tobias Berger p. 16 The Problem with Politics: An Interview with Oscar Ho John Millichap Tomorrow’s Local Library: The Asia Art Archive in Context Lee Weng Choy 24 Report on “Re: Wanchai—Hong Kong International Artists’ Workshop” Eliza Patten Do “(Hong Kong) Chinese” Artists Dream of Electric Sheep? p. 29 Norman Ford When Art Clashes in the Public Sphere— Pan Xing Lei’s Strike of Freedom Knocking on the Door of Democracy in Hong Kong Shieh-wen Chen Monumentality and Anti-Monumentality in Gu Wenda’s Forest of Stone Steles—A Retranslation and Rewriting of Tang Poetry Wu Hung From Glittering “Stars” to Shining El Dorado, or, the p. 54 “adequate attitude of art would be that with closed eyes and clenched teeth” Martina Köppel-Yang Zhang Dali: The Face of China Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky Collecting Elsewhere: An Interview with Uli Sigg Biljana Ciric A Dialogue on Contemporary Chinese Art: The One-Day Workshop “Meaning, Image, and Word” Tsao Hsingyuan p. -

Art Market in Russia. Report 2016 Year 2016 Proved That People in Russia Are Really Desperate Art Lovers

Art Market in Russia. Report 2016 Year 2016 proved that people in Russia are really desperate art lovers. How else would you explain that thousands of them spent hours in the freezing cold queueing to visit museum exhibitions? Russians were so motivated to see Valentin Serov exhibition in Tretyakov Gallery last January that the government had to bring military field kitchens in order not to let them freeze to death standing in line. Later another thousands of art-maniacs were freezing in the cold for hours to see the paintings of Ivan Aivazovsky and Raphael. Governmental statistics show that almost 120 000 000 people visited Russian museums and art galleries in 2016. Overwhelming figure. And it would be logical to assume that such a great number of experienced museum visitors was an indication of a big number of art buyers on the local market. But (spoiler alert!) it wasn’t! At least not in 2016. Overall, 2016 was ineffectual year for the Russian art market. The economic crisis affected the country more than in 2015. The business climate deteriorated. The Russian Ministry of Culture cut almost to zero the real export capa- bilities of the auctions and art galleries. Several well-known professionals of the art market suffered unconvincing lawsuits. Some of them got criminal records for «smuggling» (like dealer Sergey Stepanov) or even were put in prison (as Russian avant-garde books gallerist Anatoly Borovkov). All these cases had bad consequences for weak art market and mood of art business elite. At the same time, 2016 brought some good signs to the local art market. -

The Illusion of the Initiative an Overview of the Past Twenty Years of Media Art in Central Europe1 Miklos Peternák

The Illusion of the Initiative An Overview of the Past Twenty Years of Media Art in Central Europe1 Miklos Peternák When the political transformations began in ramifications, the entry into the European 1989–90, there were nine countries Union and the demands and opportunities (including the GDR) in this one geographical that came along with this, and, finally, region of Europe; today, at the end of 2010, globalization as the backdrop, which, there are twenty-five (and four more, if we beyond its cultural and economic effects, count all the successor states of the Soviet also made possible military control and Union). This fact alone would require an intervention, as in the case of the Yugoslav explanatory footnote longer than this entire wars. article. The above situation is further colored by What is the significance of this varied, more localized political replacement transformation, this transition? For an economies. Beyond the historical Left-Right outline of contemporary (media) art in dichotomy there has been the potential for Eastern and Central Europe (partly also more authoritarian or presidential systems, including Northern and Southern Europe sometimes drawing on more symbolism- and the Balkans) there are at least three laden atavistic outbreaks of a more blood- processes involved, and probably four— curdling nature. partly in parallel, and partly of mutual influence: the capitalist economic system As for art, the above mentioned that arose after the bankruptcy and failure of circumstances do more than just furnish the ―existing socialisms‖—or to put it another backdrop and immediate environment: in way, the transformation of dictatorships into many cases they themselves are the subject democracies—together with the global matter, whatever the medium. -

Global Interiors Living Small & Smart

ASPIRE DESIGN AND HOME JUXTAPOSITION in DESIGN GLOBAL INTERIORS LIVING SMALL & SMART ASPIREMETRO.COM WWW.ASPIREMETRO.COM 61 & INSIDE ON THE MARKET: HUDSON VALLEY | HAWAII | BROOKLYN | NAPA VALLEY universal candor SAN FRANCISCO-BASED DESIGNER JIUN HO COLLABORATES WITH A DECISIVE COUPLE TO RECONFIGURE THEIR ECLECTIC HOME TEXT MICHELE KEITH PHOTOGRAPHY MATTHEW MILLMAN tarting with designer Jiun Ho Swho hails from Malaysia, and the bio-tech executive homeowners, one African-American, his partner German; to such artworks as a larger-than-life sculpture from Cameroon and paintings from Russian conceptualists Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid; to furnishings that include a Kashan carpet from Persia to a Louis XV desk, it’s clear this house would be hard to beat in the “universal” category. Above: Skillfully concealed lighting casts a glow on the hallway’s art collection distinguished by an early-20th-century Baga Nimba shoulder mask from Guinea, West Africa. The stairs, with balustrade designed by Ho, are made of oak as is the flooring. Opposite: Viewed through an arch, the office area features a Louis XV desk. Acquired at auction, with gilt bronze embellishments, it’s made of tulipwood, amaranth and rosewood. Creating a contemporary contrast are lithographs by Antoni Tàpies, acquired by the homeowners at auction. 122 WINTER 2017-18 WWW.ASPIREMETRO.COM 123 In the light-filled living room where curves contrast with straight edges, an oil and tar on canvas by Piero Manzoni, “Genus,” draws attention to the fireplace. 124 WINTER 2017-18 WWW.ASPIREMETRO.COM 125 The homeowners left the color palette and other such crucial elements for Ho to resolve. -

Inheriting the Yugoslav Century: Art, History, and Generation

Inheriting the Yugoslav Century: Art, History, and Generation by Ivana Bago Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Kristine Stiles, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Hansen ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Branislav Jakovljević ___________________________ Neil McWilliam Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT Inheriting the Yugoslav Century: Art, History, and Generation by Ivana Bago Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies Duke University ___________________________ Kristine Stiles, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Hansen ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Branislav Jakovljević ___________________________ Neil McWilliam An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Ivana Bago 2018 Abstract The dissertation examines the work contemporary artists, curators, and scholars who have, in the last two decades, addressed urgent political and economic questions by revisiting the legacies of the Yugoslav twentieth century: multinationalism, socialist self-management, non- alignment, and -

I Is for 3 6 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 Institute Local

I is for Institute Local Context 2/22, 6:30 PM 3 Asian Arts Initiative 6 The Fabric Workshop and Museum 9 Fleisher Art Memorial 11 FJORD Gallery 13 Marginal Utility 15 Mural Arts Philadelphia 17 Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) 19 Philadelphia Contemporary 21 Philadelphia Museum of Art 24 Philadelphia Photo Arts Center (PPAC) 26 The Print Center 28 Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery, The University of the Arts 30 Temple Contemporary 32 The Village of Arts and Humanities 34 Ulises 36 Vox Populi What’s in a name? This is the question underlying our year-long investigation into ICA: how it came to be, what it means now, and how we might imagine it in the future. ASIAN ARTS INITIATIVE Address 1219 Vine Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 Website asianartsinitiative.org Founding Date Spring, 1993 Staff Size 7 Full-time, 7 Part-time. Do you have a physical location? Yes Do you have a collection? No Logo Mission Statement A meeting place, an idea lab, a support system, and an engine for positive change, Asian Arts Initiative strives to empower communities through the richness of art. We believe in a universal human capacity for creativity, and we support local art and artists as a means of interpreting, sharing, and shaping contemporary cultural identity. Created in 1993 in response to community concerns about rising racial tension, we serve a diverse constituency of both youth and adults—Asian immigrants, Asian Americans born in the U.S., and non-Asians—who come together to give voice to experiences of cultural identity and heritage and claim the power of art- making as a vital form of expression and catalyst for social change. -

Mapping the Landscape of Socially Engaged Artistic Practice

Mapping the Landscape of Socially Engaged Artistic Practice Alexis Frasz & Holly Sidford Helicon Collaborative artmakingchange.org 1 “Artists are the real architects of change, not the political legislators who implement change after the fact.” William S. Burroughs 2 table of contents 4 28 purpose of the research snapshots of socially engaged art making Rick Lowe, Project Row Houses | Laurie Jo Reynolds, Tamms Year Ten | Mondo Bizarro + Art Spot Productions, 9 Cry You One | Hank Willis Thomas | Alaskan Native methodology Heritage Center | Queens Museum and Los Angeles Poverty Department | Tibetan Freedom Concerts | Alicia Grullón | Youth Speaks, The Bigger Picture 11 findings Defining “Socially Engaged Art” | Nine Variations 39 in Practice | Fundamental Components (Intentions, supporting a dynamic ecosystem Skills, and Ethics) | Training | Quality of Practice 44 resources acknowledgements people interviewed or consulted | training programs | impact | general resources | about helicon | acknowledgments | photo credits purpose of the research Helicon Collaborative, supported by the Robert Raus- tural practices of disenfranchised communities, such chenberg Foundation, began this research in 2015 in as the African-American Mardi Gras Indian tradition order to contribute to the ongoing conversation on of celebration and protest in New Orleans. Finally, we “socially engaged art.” Our goal was to make this included artists that are practicing in the traditions important realm of artmaking more visible and legible of politically-inspired art movements, such as the to both practitioners and funders in order to enhance Chicano Arts Movement and the settlement house effective practice and expand resources to support it. movement, whose origins were embedded in creat- ing social change for poor or marginalized people. -

GORGONA 1959 – 1968 Independent Artistic Practices in Zagreb Retrospective Exhibition from the Marinko Sudac Collection

GORGONA 1959 – 1968 Independent Artistic Practices in Zagreb Retrospective Exhibition from the Marinko Sudac Collection 14 September 2019 – 5 January 2020 During the period of socialism, art in Yugoslavia followed a different path from that in Hungary. Furthermore, its issues, reference points and axes were very different from the trends present in other Eastern Bloc countries. Looking at the situation using traditional concepts and discourse of art in Hungary, one can see the difference in the artistic life and cultural politics of those decades in Yugoslavia, which was between East and West at that time. The Gorgona group was founded according to the idea of Josip Vaništa and was active as an informal group of painters, sculptors and art critics in Zagreb since 1959. The members were Dimitrije Bašičević-Mangelos, Miljenko Horvat, Marijan Jevšovar, Julije Knifer, Ivan Kožarić, Matko Meštrović, RadoslavPutar, Đuro Seder, and Josip Vaništa. The activities of the group consisted of meetings at the Faculty of Architecture, in their flats or ateliers, in collective works (questionnaires, walks in nature, answering questions or tasks assigned to them or collective actions). In the rented space of a picture-framing workshop in Zagreb, which they called Studio G and independently ran, from 1961 to 1963 they organized 14 exhibitions of various topics - from solo and collective exhibitions by group's members and foreign exhibitors to topical exhibitions. The group published its anti-magazine Gorgona, one of the first samizdats post WWII. Eleven issues came out from 1961 to 1966, representing what would only later be called a book as artwork. The authors were Gorgona members or guests (such as Victor Vasarely or Dieter Roth), and several unpublished drafts were made, including three by Pierre Manzoni. -

Detki V Kletke: the Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children's Literature and Unofficial Poetry

Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children's Literature and Unofficial Poetry The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Morse, Ainsley. 2016. Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children's Literature and Unofficial Poetry. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493521 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children’s Literature and Unofficial Poetry A dissertation presented by Ainsley Elizabeth Morse to The Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Slavic Languages and Literatures Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2016 © 2016 – Ainsley Elizabeth Morse. All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Stephanie Sandler Ainsley Elizabeth Morse Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children’s Literature and Unofficial Poetry Abstract Since its inception in 1918, Soviet children’s literature was acclaimed as innovative and exciting, often in contrast to other official Soviet literary production. Indeed, avant-garde artists worked in this genre for the entire Soviet period, although they had fallen out of official favor by the 1930s. This dissertation explores the relationship between the childlike aesthetic as expressed in Soviet children’s literature, the early Russian avant-garde and later post-war unofficial poetry.