The Contemporary Significance of Design in Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Is for 3 6 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 Institute Local

I is for Institute Local Context 2/22, 6:30 PM 3 Asian Arts Initiative 6 The Fabric Workshop and Museum 9 Fleisher Art Memorial 11 FJORD Gallery 13 Marginal Utility 15 Mural Arts Philadelphia 17 Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) 19 Philadelphia Contemporary 21 Philadelphia Museum of Art 24 Philadelphia Photo Arts Center (PPAC) 26 The Print Center 28 Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery, The University of the Arts 30 Temple Contemporary 32 The Village of Arts and Humanities 34 Ulises 36 Vox Populi What’s in a name? This is the question underlying our year-long investigation into ICA: how it came to be, what it means now, and how we might imagine it in the future. ASIAN ARTS INITIATIVE Address 1219 Vine Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 Website asianartsinitiative.org Founding Date Spring, 1993 Staff Size 7 Full-time, 7 Part-time. Do you have a physical location? Yes Do you have a collection? No Logo Mission Statement A meeting place, an idea lab, a support system, and an engine for positive change, Asian Arts Initiative strives to empower communities through the richness of art. We believe in a universal human capacity for creativity, and we support local art and artists as a means of interpreting, sharing, and shaping contemporary cultural identity. Created in 1993 in response to community concerns about rising racial tension, we serve a diverse constituency of both youth and adults—Asian immigrants, Asian Americans born in the U.S., and non-Asians—who come together to give voice to experiences of cultural identity and heritage and claim the power of art- making as a vital form of expression and catalyst for social change. -

Mapping the Landscape of Socially Engaged Artistic Practice

Mapping the Landscape of Socially Engaged Artistic Practice Alexis Frasz & Holly Sidford Helicon Collaborative artmakingchange.org 1 “Artists are the real architects of change, not the political legislators who implement change after the fact.” William S. Burroughs 2 table of contents 4 28 purpose of the research snapshots of socially engaged art making Rick Lowe, Project Row Houses | Laurie Jo Reynolds, Tamms Year Ten | Mondo Bizarro + Art Spot Productions, 9 Cry You One | Hank Willis Thomas | Alaskan Native methodology Heritage Center | Queens Museum and Los Angeles Poverty Department | Tibetan Freedom Concerts | Alicia Grullón | Youth Speaks, The Bigger Picture 11 findings Defining “Socially Engaged Art” | Nine Variations 39 in Practice | Fundamental Components (Intentions, supporting a dynamic ecosystem Skills, and Ethics) | Training | Quality of Practice 44 resources acknowledgements people interviewed or consulted | training programs | impact | general resources | about helicon | acknowledgments | photo credits purpose of the research Helicon Collaborative, supported by the Robert Raus- tural practices of disenfranchised communities, such chenberg Foundation, began this research in 2015 in as the African-American Mardi Gras Indian tradition order to contribute to the ongoing conversation on of celebration and protest in New Orleans. Finally, we “socially engaged art.” Our goal was to make this included artists that are practicing in the traditions important realm of artmaking more visible and legible of politically-inspired art movements, such as the to both practitioners and funders in order to enhance Chicano Arts Movement and the settlement house effective practice and expand resources to support it. movement, whose origins were embedded in creat- ing social change for poor or marginalized people. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 26, 2021 CONTACT: Mayor's Press

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 26, 2021 CONTACT: Mayor’s Press Office 312.744.3334 [email protected] MAYOR LIGHTFOOT ANNOUNCES SHOWTIME® IS DONATING $500,000 FOR SOUTH AND WEST SIDE NEIGHBORHOOD BEAUTIFICATION AND ARTS PROJECTS Donation to Greencorps Chicago green job training program and Chicago Public Art Group focuses on Chicago neighborhoods where the network’s critically acclaimed drama series “The Chi” is filmed CHICAGO – Mayor Lori E. Lightfoot joined Puja Vohra, Executive Vice President of Marketing and Strategy for SHOWTIME, and cast members from its Chicago-based hit show “The Chi,” along with community leaders, today to announce a $500,000 donation from the network to the City’s Greencorps Chicago green job training program and the Chicago Public Art Group. The funding will support and invest in the City’s South and West sides, which have served as key locations for the SHOWTIME drama series “The Chi,” created by Lena Waithe, for four seasons. The grant will pay for the clean-up and beautification of 32 empty lots and six accompanying art installations in Bronzeville and North Lawndale, areas that are part of Mayor Lightfoot’s INVEST South/West initiative that is designed to revitalize community areas in Chicago that have suffered from a legacy of under-investment. "From vibrantly depicting our city's neighborhoods on 'The Chi' to now investing in our city's sustainability, employment and art initiatives, SHOWTIME has demonstrated its commitment to supporting and uplifting our residents," said Mayor Lightfoot. "This donation will make a real difference in our communities and strengthen two of our greatest community-based programs, which are doing incredible work to improve Chicago. -

Future Forward Seattle Waterfront Pier 62 Call for Artists

Future Forward Seattle Waterfront Pier 62 Call for Artists 08/13/2020 Introduction Seattle’s future Waterfront Park is more than a park — it is a once-in-a-generation opportunity where the community’s values, vision, and investments align to achieve lasting economic, social, and environmental value — now, and for the benefit of future generations. This monumental opportunity has led to development of an Artist-In-Residence program that brings new energy and vision to creating a “waterfront for all.” Takiyah Ward was recently named the Future Forward Virtual Artist In Residence by Friends. Leading the artistic vision, Takiyah designed the framework for engaging artists in a range of opportunities to activate the Seattle waterfront. This framework focuses on creative projects that invite exploration of stories and experiences focused on insights of the past, engagement with the present, and vision for the future — PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE. In this context, three distinct projects will be implemented with activities, activations, and installations to illuminate each theme. The current call for artists is for Pier 62 and seeks an artist collective (a group of two or more artists) to explore the theme of PRESENT through the creation of a temporary light sculpture and up to 40 lanterns or luminaries. DETAILS OF THE ARTIST CALL Location: Pier 62 Theme: PRESENT - How do we honor our elders, determine our self, and protect our youth? Artist In Residence Vision Statement “Using varying scales and quantity, Pier 62 will be the canvas for embodying the ideas of artists speaking to present circumstances in relation to elders and youth. -

Ephemera Labels WWAR EPHEMERA LABELS 1 EXTENDED LABELS

We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85 Ephemera Labels WWAR EPHEMERA LABELS 1 EXTENDED LABELS Larry Neal (Born 1937 in Atlanta; died 1981 in Hamilton, New York) “Any Day Now: Black Art and Black Liberation,” Ebony, August 1969 Jet, January 28, 1971 Printed magazines Collection of David Lusenhop During the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, publications marketed toward black audiences chronicled social, cultural, and political developments, covering issues of particular concern to their readership in depth. The activities and development of the Black Arts Movement can be traced through articles in Ebony, Black World, and Jet, among other publications; in them, artists documented the histories of their collectives and focused on the purposes and significance of art made by and for people of color. WWAR EPHEMERA LABELS 2 EXTENDED LABELS Weusi Group Portrait, early 1970s Photographic print Collection of Ronald Pyatt and Shelley Inniss This portrait of the Weusi collective was taken during the years in which Kay Brown was the sole female member. She is seated on the right in the middle row. WWAR EPHEMERA LABELS 3 EXTENDED LABELS First Group Showing: Works in Black and White, 1963 Printed book Collection of Emma Amos Jeanne Siegel (Born 1929 in United States; died 2013 in New York) “Why Spiral?,” Art News, September 1966 Facsimile of printed magazine Brooklyn Museum Library Spiral’s name, suggested by painter Hale Woodruff, referred to “a particular kind of spiral, the Archimedean one, because, from a starting point, it moves outward embracing all directions yet constantly upward.” Diverse in age, artistic styles, and interests, the artists in the group rarely agreed; they clashed on whether a black artist should be obliged to create political art. -

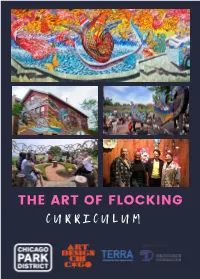

THE ART of FLOCKING CURRICULUM the Art of Flocking Curriculum

THE ART OF FLOCKING CURRICULUM The Art of Flocking Curriculum “There is an art to flocking: staying close enough not to crowd each other, aligned enough to maintain a shared direction, and cohesive enough to always move towards each other.” - adrienne maree brown The Art of Flocking: Cultural Stewardship in the Parks is a celebration of Chicago’s community-based art practices co-facilitated by the Chicago Park District and the Terra Foundation for American Art. A proud member of Art Design Chicago, this initiative aims to uplift Chicago artists with deep commitments to social justice, cultural preservation, community solidarity, and structural transformation. Throughout the summer of 2018, The Art of Flocking engaged 2,500 youth and families through 215 public programs and community exhibitions exploring the histories and legacies of Mexican-American public artist Hector Duarte and Sapphire and Crystals, Chicago's first and longest-standing Black women's artist collective.The Art of Flocking featured two beloved Chicago Park District programs: ArtSeed, designed to engage children ages 3 and up as well as their families and caretakers in 18 parks and playgrounds; and Young Cultural Stewards a multimedia youth fellowship centering young people ages 12–14 with regional hubs across the North, West, and South sides of Chicago. ArtSeed: Mobile Creative Play ArtSeed engages over 2,000 youth (ages 3-12) across 18 parks through storytelling, music, movement, and nature play rooted in neighborhood stories. Children explore the histories and legacies of Chicago's community-based artists and imagine creative solutions to challenges in their own neighborhoods. Teaching artists engage practice of social emotional learning, foundations in social justice, and trauma-informed pedagogy to cultivate children and families invested in fostering the cultural practices and creative capital of their parks and communities. -

The Benefits and Limitations of Artist-Run Organizations in Columbus, Ohio

THE BENEFITS AND LIMITATIONS OF ARTIST-RUN ORGANIZATIONS IN COLUMBUS, OHIO A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Melissa Ann Keeley, B.A. The Ohio State University 2008 Masters Examination Committee: Approved by: Dr. Wayne Lawson, Adviser Dr. Margaret J. Wyszomirski ____________________________________ Adviser Graduate Program in Arts Policy & Administration Copyright by Melissa Ann Keeley 2008 ABSTRACT The creative sector of any community provides important economic and social benefits. Research has shown that supporting a thriving arts and culture sector provides not only monetary returns on public investment but also helps create a positive image of a city that is in turn attractive to new businesses and a talented workforce. Furthermore, researchers have found that the presence of artists within a city is a good judge of a community’s cultural vitality and that cities should look to attract and retain artists to create new and innovative arts experiences while enhancing and building the creative capital within the community. However, attracting and retaining artists is not always easy. Artists are highly mobile and frequently leave “second tier” cities to move to the premier art cities of New York and Los Angeles. In order to attract and retain artists to a community like Columbus, Ohio the city needs to support organizations and groups that help develop a hospitable environment for artists. A hospitable environment includes access to studio space and equipment, peer support, ability to gain exposure and exhibit work, and also a high quality of life at a reasonable cost. -

Better Together – an Inquiry Into Collective Art Practice

Better Together An Inquiry into Collective Art Practice Robin Hewlett, Editor The Collective Artist Residency Project The STUDIO for Creative Inquiry was founded in 1989 with the mission of supporting issues, in a manor that models a cooperative philosophy and interdisciplinary projects, bringing together the arts, science, technology and humanities. counters the competitive nature of capitalist culture. From the beginning, this mission allowed the STUDIO to engage with collectives In 2004 – 2005, The STUDIO hosted two artists who work in involving a diverse range of artists, scientists and technologists. These interactions collectives: Nathan Martin and Grisha Coleman. They received shed light on the critically engaged and collaborative approach of collectives. Looking administrative and technical support, along with a salaried back over nearly two decades, one can see the significant contribution that collectives fellowship for one year. The fellowships also included travel have made, and continue to make in the art world and beyond. The work of STUDIO and relocation funding, as well as a project budget. Funding fellows such as Critical Art Ensemble, subRosa and Institute for Applied Autonomy for the Collective Artist Residency Project was provided by represent an important trend in art making. the National Endowment for the Arts, Heinz Endowments, Collective organizing has a long history in social, political and economic realms. In the PA Council on the Arts. The Multicultural Arts Initiative, and essay “Periodising Collectivism,” Gregory Sholette and Blake Stimson claim it is “the the Center for Arts in Society at Carnegie Mellon, provided desire to speak as a collective voice that has long fuelled the social imagination of additional funding for the artists’ projects. -

Springer Series on Cultural Computing

Springer Series on Cultural Computing Editor-in-Chief Ernest Edmonds, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia Editorial Board Frieder Nake, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany Nick Bryan-Kinns, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK Linda Candy, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia David England, John Moores University, Liverpool, UK Andrew Hugill, De Montfort University, Leicester, UK Shigeki Amitani, Adobe Systems Inc., Tokyo, Japan Doug Riecken, Columbia University, New York, USA Jonas Lowgren, Malmö University, Sweden For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/10481 Vladimir Geroimenko Editor Augmented Reality Art From an Emerging Technology to a Novel Creative Medium 123 Editor Vladimir Geroimenko School of Art and Media Plymouth University Plymouth, Devon, UK ISSN 2195-9056 ISSN 2195-9064 (electronic) ISBN 978-3-319-06202-0 ISBN 978-3-319-06203-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-06203-7 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2014941933 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. -

Art in Public Places Meeting Packet 11.29.2018

ART IN PUBLIC PLACES Thursday, November 29, 2018 City Council Conference Room 200 Lincoln Ave. 505-955-6707 5:30 PM 1. Call to Order 2. Roll Call 3. Approval of Agenda 4. Approval of Minutes a) August 23, 2018 b) October 25, 2018 5. Report of the Chair a) Appointment of a nominating committee 6. Action Items a) Request for approval of 2019 Committee Meeting Schedule (Rod Lambert, Community Gallery Manager, [email protected], 955-6705) b) Request for approval of City parking garage mural project: (Rod Lambert) i. Request for approval of project budget of $50,000 (Rod Lambert). ii. Request for approval of selection committee (Rod Lambert). c) Request for approval of Fall/Winter 2019 Community Gallery exhibit theme, “A Longer Table” (Rod Lambert). d) Request for approval of 2019 Community Youth Mural Pilot Project (Debra Garcia y Griego, Director, [email protected], 955.6653). e) Request for approval of change in design and corresponding increase in budget in the amount of $4,626 ($14,626 total) for Telepoem Booth project (Debra Garcia y Griego). 7. Discussion Items a) Discussion of Pop Up exhibit policies (Rod Lambert) 8. Adjourn Persons with disabilities in need of accommodations, contact the City Clerk’s office at 955-6520 five (5) working days prior to meeting date RECEIVED AT THE CITY CLERK’S OFFICE DATE:__11/19/2018________ TIME:__8:24 AM__________ Proposed 2019 ART IN PUBLIC PLACES COMMITTEE MEETING SCHEDULE Monthly Meetings Meetings begin at 5:00 p.m. in the City Councilors’ Conference Room, City Hall, 200 Lincoln Avenue. -

Carl Joe Williams B.1970, New Orleans, LA

Carl Joe Williams B.1970, New Orleans, LA Education Atlanta College of Art, Atlanta, GA The New Orleans Center for Creative Arts, New Orleans, LA Solo Exhibitions 2020 “Atrium Project” MOCA Jacksonville, Cultural Institute of UNF, Jacksonville, FL 2017 “Sacred Blues and Old Stories” 5 Press Street Gallery, New Orleans, LA 2014 “Viral Realities” Staple Goods Gallery, New Orleans, LA 2013 “Shades of Perception” Ohr-O'Keefe Museum Of Art Biloxi, MS “In the Beginning....There was no Beginning” The Front Gallery, New Orleans, LA “Rhythmic Souls” Delgado Community College, New Orleans, LA 2012 “Fractured Souls” The Front Gallery, New Orleans, LA. “Soul Searcher” M Francis Gallery, New Orleans, LA. 2010 “Synesthesia: A Blending of the Senses” McKenna Museum of African American Art, New Orleans, LA. 2002 “Coded Memories” Hammonds House Galleries, Atlanta, GA 2000 “Visual Poetry”, Swan House Coach Gallery, Atlanta, GA Carl Joe Williams B.1970, New Orleans, LA 1997 “Carl Joe Williams” Modern Primitive Galley, Atlanta, GA 1990 “Journeys” Gallery 100 Atlanta College of Art, Atlanta, GA Group Exhibitions 2020 “Afrocosmologies” Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT “The Effect of Color” Gryder Gallery, New Orleans, LA “Art in the Time of Empathy” Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans, LA 2019 “Prizm Art Fair” Art Basel Miami, Miami, FL "Art for Art’s Sake" Level Artist Collective, Ogden Museum, New Orleans, LA “Dorseys’ Black Art in America Collection” Houston Museum of African American Culture, Houston, TX "Essential Presence", PFF Collection, -

9780816644629.Pdf

COLLECTIVISM AFTER ▲ MODERNISM This page intentionally left blank COLLECTIVISM ▲ AFTER MODERNISM The Art of Social Imagination after 1945 BLAKE STIMSON & GREGORY SHOLETTE EDITORS UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA PRESS MINNEAPOLIS • LONDON “Calling Collectives,” a letter to the editor from Gregory Sholette, appeared in Artforum 41, no. 10 (Summer 2004). Reprinted with permission of Artforum and the author. An earlier version of the introduction “Periodizing Collectivism,” by Blake Stimson and Gregory Sholette, appeared in Third Text 18 (November 2004): 573–83. Used with permission. Copyright 2007 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Collectivism after modernism : the art of social imagination after 1945 / Blake Stimson and Gregory Sholette, editors. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8166-4461-2 (hc : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8166-4461-6 (hc : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8166-4462-9 (pb : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8166-4462-4 (pb : alk. paper) 1. Arts, Modern—20th century—Philosophy. 2. Collectivism—History—20th century. 3. Art and society—History—20th century. I. Stimson, Blake. II. Sholette, Gregory. NX456.C58 2007 709.04'5—dc22 2006037606 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer.