Mapping the Landscape of Socially Engaged Artistic Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beastie Boys Square Resolution

Draft of Resolution, Provided to CB3 by Applicant CB3 Beastie Boys Square Resolution Whereas the Beastie Boys were established in July 1981 as part of the Lower East Side’s CBGB punk music scene, and frequently played in that venue; Whereas the Beastie Boys’ first album, “Polly Wog Stew,” was recorded at 171A Studios, located at 171 Avenue A in the East Village; Whereas in 1984, the Beastie Boys were the first white and the first Jewish hip hop group signed to Def Jam records, where they played a significant, early role breaking down racial barriers in 1980s music between rock (white audience) and hip hop (black and Latino audience), which in turn led to a greater cultural understanding and historic reduction in the racial divide between the groups according to the book and 2013 VH1 miniseries “The Tanning of America”; Whereas in 1988 the group released the album “Paul’s Boutique,” which brought the corner of Ludlow and Rivington Streets on the Lower East Side international fame by featuring an oversized picture of the corner on the cover of the album; Whereas the cover art from “Paul’s Boutique,” which Rolling Stone magazine named the 156th greatest album of all time in 2009 and the Village Voice named 3rd on its list of the 50 Most New York Albums Ever in 2013, continues to draw fans from around the world to the corner of Ludlow and Rivington Streets; Whereas, the Beastie Boys meet CB3’s street renaming guidelines because they have achieved “exceptional and highly acclaimed accomplishment or involvement linked to Manhattan Community -

The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle: a Strategic and Historical Analysis

ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle: A Strategic and Historical Analysis Tenzin Dorjee ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES Cover photos: (l) John Ackerly, 1987, (r) Invisible Tibet Blog SERIES EDITOR: Maciej Bartkowski John Ackerly’s photo of the first major demonstration in Lhasa in 1987 CONTACT: [email protected] became an emblem for the Tibet movement. The monk Jampa Tenzin, who is being lifted by fellow protesters, had just rushed into a burning VOLUME EDITORS: Hardy Merriman, Amber French, police station to rescue Tibetan detainees. With his arms charred by the Cassandra Balfour flames, he falls in and out of consciousness even as he leads the crowd CONTACT: [email protected] in chanting pro-independence slogans. The photographer John Ackerly Other volumes in this series: became a Tibet advocate and eventually President of the International Campaign for Tibet (1999 to 2009). To read more about John Ackerly’s The Power of Staying Put: Nonviolent Resistance experience in Tibet, see his book co-authored by Blake Kerr, Sky Burial: against Armed Groups in Colombia, Juan Masullo An Eyewitness Account of China’s Brutal Crackdown in Tibet. (2015) Invisible Tibet Blog’s photo was taken during the 2008 Tibetan uprising, The Maldives Democracy Experience (2008-13): when Tibetans across the three historical provinces of Tibet rose up From Authoritarianism to Democracy and Back, to protest Chinese rule. The protests began on March 10, 2008, a few Velezinee Aishath (2015) months ahead of the Beijing Olympic Games, and quickly became the largest, most sustained nonviolent movement Tibet has witnessed. Published by the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict The designations used and material presented in this publication do P.O. -

I Is for 3 6 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 Institute Local

I is for Institute Local Context 2/22, 6:30 PM 3 Asian Arts Initiative 6 The Fabric Workshop and Museum 9 Fleisher Art Memorial 11 FJORD Gallery 13 Marginal Utility 15 Mural Arts Philadelphia 17 Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) 19 Philadelphia Contemporary 21 Philadelphia Museum of Art 24 Philadelphia Photo Arts Center (PPAC) 26 The Print Center 28 Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery, The University of the Arts 30 Temple Contemporary 32 The Village of Arts and Humanities 34 Ulises 36 Vox Populi What’s in a name? This is the question underlying our year-long investigation into ICA: how it came to be, what it means now, and how we might imagine it in the future. ASIAN ARTS INITIATIVE Address 1219 Vine Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 Website asianartsinitiative.org Founding Date Spring, 1993 Staff Size 7 Full-time, 7 Part-time. Do you have a physical location? Yes Do you have a collection? No Logo Mission Statement A meeting place, an idea lab, a support system, and an engine for positive change, Asian Arts Initiative strives to empower communities through the richness of art. We believe in a universal human capacity for creativity, and we support local art and artists as a means of interpreting, sharing, and shaping contemporary cultural identity. Created in 1993 in response to community concerns about rising racial tension, we serve a diverse constituency of both youth and adults—Asian immigrants, Asian Americans born in the U.S., and non-Asians—who come together to give voice to experiences of cultural identity and heritage and claim the power of art- making as a vital form of expression and catalyst for social change. -

NEW MUSIC on COMPACT DISC 4/16/04 – 8/31/04 Amnesia

NEW MUSIC ON COMPACT DISC 4/16/04 – 8/31/04 Amnesia / Richard Thompson. AVRDM3225 Flashback / 38 Special. AVRDM3226 Ear-resistible / the Temptations. AVRDM3227 Koko Taylor. AVRDM3228 Like never before / Taj Mahal. AVRDM3229 Super hits of the '80s. AVRDM3230 Is this it / the Strokes. AVRDM3231 As time goes by : great love songs of the century / Ettore Stratta & his orchestra. AVRDM3232 Tiny music-- : songs from the Vatican gift shop / Stone Temple Pilots. AVRDM3233 Numbers : a Pythagorean theory tale / Cat Stevens. AVRDM3234 Back to earth / Cat Stevens. AVRDM3235 Izitso / Cat Stevens. AVRDM3236 Vertical man / Ringo Starr. AVRDM3237 Live in New York City / Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band. AVRDM3238 Dusty in Memphis / Dusty Springfield. AVRDM3239 I'll be around : and other hits. AVRDM3240 No one does it better / SoulDecision. AVRDM3241 Doin' something / Soulive. AVRDM3242 The very thought of you: the Decca years, 1951-1957 /Jeri Southern. AVRDM3243 Mighty love / Spinners. AVRDM3244 Candy from a stranger / Soul Asylum. AVRDM3245 Gone again / Patti Smith. AVRDM3246 Gung ho / Patti Smith. AVRDM3247 Freak show / Silverchair. AVRDM3248 '60s rock. The beat goes on. AVRDM3249 ‘60s rock. The beat goes on. AVRDM3250 Frank Sinatra sings his greatest hits / Frank Sinatra. AVRDM3251 The essence of Frank Sinatra / Frank Sinatra. AVRDM3252 Learn to croon / Frank Sinatra & Tommy Dorsey and his orchestra. AVRDM3253 It's all so new / Frank Sinatra & Tommy Dorsey and his orchestra. AVRDM3254 Film noir / Carly Simon. AVRDM3255 '70s radio hits. Volume 4. AVRDM3256 '70s radio hits. Volume 3. AVRV3257 '70s radio hits. Volume 1. AVRDM3258 Sentimental favorites. AVRDM3259 The very best of Neil Sedaka. AVRDM3260 Every day I have the blues / Jimmy Rushing. -

The Contemporary Significance of Design in Art

THE CONTEMPORARY SIGNIFICANCE OF DESIGN IN ART by ARNO MORLAND submitted to PROF. KAREL NEL in January 2005 in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree MA (FA) by Coursework in the Department of Fine Art University of the Witwatersrand School of the Arts Table of Contents 1. Introduction………………………………………………………..……….…p.1 2. The conceptual climate of contemporary art production………….……….…p.5 3. The social context of contemporary art production……………….………….p.12 4. The adoption of design as creative idiom in contemporary art….……………p.18 5. The artist as designer…………………………………….……………………p.21 6. Conclusion………………………………………………….…………………p.27 7. Bibliography……………………………………………….………………….p.30 8. Illustrations……………………………………………………………………p.32 THE CONTEMPORARY SIGNIFICANCE OF DESIGN IN ART By Arno Morland 1. Introduction Do we live by design? Certainly many of us will live out the majority of our lives in environments that are almost entirely ‘human-made’. If the apparent orderly functionality of nature is likely to remain, for the time being, philosophically controversial, the origin of our human-made environment in design is surely beyond dispute. If this is indeed the case, then the claim by Dianne Pilgrim, director of the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, that “design affects our lives every second of the day”, may not be as immodest as it appears to be at first (2000: 06). Perhaps then, it is with some justification that eminent art critic Hal Foster refers to the notion of “total design” to describe what he sees as contemporary culture’s state of comprehensive investment in design (2002: 14). For Foster, we live in a time of “blurred disciplines, of objects treated as mini-subjects”, a time when “everything…seems to be regarded as so much design” (2002: 17). -

Sylvia Massy RUSSELL COTTIER Talks Unusual Recording Techniques with the Globe-Trotting Engineer, Producer, Author and Artist

Interview Sylvia Massy RUSSELL COTTIER talks unusual recording techniques with the globe-trotting engineer, producer, author and artist ylvia Massy needs almost no In the ‘90s, Massy produced material for Red introduction to those of us who grew Hot Chili Peppers, Sevendust and Powerman up listening to rock in the ‘80s and ‘90s. 5000. In 1997 Massy mixed the Beastie Boys’ SMassy started off in the punk band Tibetan Freedom Concert in New York. Massy Revolver but soon moved on to producing, engineered and mixed several projects for / Massy mixes the masters in France including co-producing with Kirk Hammett, and producer Rick Rubin for his label American soon ended up at Larrabee Studios working Recordings, including Johnny Cash’s album In 2001, Massy acquired the Weed Palace with big name acts like Prince, Paula Abdul, Unchained, which won a Grammy award for Best Theater in Weed, California, and operated it as a Julio Iglesias, Seal and Aerosmith. After a hit Country Album in 1997. With Rubin, she also recording studio for 11 years, with clients with Green Jellö, Massy went on to rack up recorded Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, including Sublime, Dishwalla, Swirl 360, credits with the likes of Tool, Skunk Anansie and Slayer, Donovan, Geto Boys, the Black Crowes, Econoline Crush, Cog, Spiderbait, Norma Jean, many more. and System of a Down’s debut album. Built To Spill and From First To Last. 28 / November/December 2018 But then you moved to LA? would be in a live show. Yes, there was a point at which it became With the drums I would want everything to obvious that if I really wanted to make this as a be as well recorded as possible with some career, I would have to move to where the experimental things that perhaps would be industry was, and that was in Los Angeles. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 26, 2021 CONTACT: Mayor's Press

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 26, 2021 CONTACT: Mayor’s Press Office 312.744.3334 [email protected] MAYOR LIGHTFOOT ANNOUNCES SHOWTIME® IS DONATING $500,000 FOR SOUTH AND WEST SIDE NEIGHBORHOOD BEAUTIFICATION AND ARTS PROJECTS Donation to Greencorps Chicago green job training program and Chicago Public Art Group focuses on Chicago neighborhoods where the network’s critically acclaimed drama series “The Chi” is filmed CHICAGO – Mayor Lori E. Lightfoot joined Puja Vohra, Executive Vice President of Marketing and Strategy for SHOWTIME, and cast members from its Chicago-based hit show “The Chi,” along with community leaders, today to announce a $500,000 donation from the network to the City’s Greencorps Chicago green job training program and the Chicago Public Art Group. The funding will support and invest in the City’s South and West sides, which have served as key locations for the SHOWTIME drama series “The Chi,” created by Lena Waithe, for four seasons. The grant will pay for the clean-up and beautification of 32 empty lots and six accompanying art installations in Bronzeville and North Lawndale, areas that are part of Mayor Lightfoot’s INVEST South/West initiative that is designed to revitalize community areas in Chicago that have suffered from a legacy of under-investment. "From vibrantly depicting our city's neighborhoods on 'The Chi' to now investing in our city's sustainability, employment and art initiatives, SHOWTIME has demonstrated its commitment to supporting and uplifting our residents," said Mayor Lightfoot. "This donation will make a real difference in our communities and strengthen two of our greatest community-based programs, which are doing incredible work to improve Chicago. -

The Lion King We Bring You a Fascinating Inside Look at Official Photography Studio the Highest Grossing Broadway Show of All Time

WWW.WIREWEEKLY.COM DISTRIBUTED EVERY THURSDAY IN MIAMI, THE BEACHES, AND FORT LAUDERDALE • THE LONGEST-RUNNING WEEKLY ON SOUTH BEACH “LIKE” US /WIREMAGAZINE & STAY TUNED FOR WWW.WIREMAG.COM COMING THIS SUMMER ISSUE #19 | 05/10/12 2 | wire magazine | issue #19, 2012 | www.wireweekly.com | facebook | twitter EDITOR IN CHIEF’S NOTE WIRE IS GROWING. PLUS TAKING CARE OF MOM BREAKING NEWS: Rafa Carvajal As Wire was going to press we heard the news Publisher/Editor in Chief that President Obama supports same-sex mar- riage - quite a contrast to voters in North Caro- Associate Publisher lina passing Amendment One to their constitu- tion. Jesse Spencer In last week’s column I shared with you that Editor Wire Magazine and Wire Media Group will James Cubby have a new Internet home at www.wiremag. com, a new lifestyle website for the LGBT com- Associate Editor munity coming this summer. As part of Wire’s Antwyone Ingram continued growth in print, online, and social media, it is also necessary to continue adding Design & Production Director people to our organization who can help us Jose Gonzalez build the team that will help craft and implement many new initiatives in 2012. I am happy to Columnists announce that Antwyone Ingram is joining the Alfredo Barrios Wire Magazine team as Associate Editor. Ant- Alyn Darnay wyone will be working very closely with me to Dane Steele Green help us grow Wire Magazine, create and host Ken Hunt new events, and launch and run our new web- Dr. Gregg A Pizzi site at www.wiremag.com. -

Future Forward Seattle Waterfront Pier 62 Call for Artists

Future Forward Seattle Waterfront Pier 62 Call for Artists 08/13/2020 Introduction Seattle’s future Waterfront Park is more than a park — it is a once-in-a-generation opportunity where the community’s values, vision, and investments align to achieve lasting economic, social, and environmental value — now, and for the benefit of future generations. This monumental opportunity has led to development of an Artist-In-Residence program that brings new energy and vision to creating a “waterfront for all.” Takiyah Ward was recently named the Future Forward Virtual Artist In Residence by Friends. Leading the artistic vision, Takiyah designed the framework for engaging artists in a range of opportunities to activate the Seattle waterfront. This framework focuses on creative projects that invite exploration of stories and experiences focused on insights of the past, engagement with the present, and vision for the future — PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE. In this context, three distinct projects will be implemented with activities, activations, and installations to illuminate each theme. The current call for artists is for Pier 62 and seeks an artist collective (a group of two or more artists) to explore the theme of PRESENT through the creation of a temporary light sculpture and up to 40 lanterns or luminaries. DETAILS OF THE ARTIST CALL Location: Pier 62 Theme: PRESENT - How do we honor our elders, determine our self, and protect our youth? Artist In Residence Vision Statement “Using varying scales and quantity, Pier 62 will be the canvas for embodying the ideas of artists speaking to present circumstances in relation to elders and youth. -

Proquest Dissertations

Forging a Buddhist Cinema: Exploring Buddhism in Cinematic Representations of Tibetan Culture by Mona Harnden-Simpson B.A. (Honours), Film Studies, Carleton University A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Film Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario August 23, 2011 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-83072-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-83072-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lntemet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Ephemera Labels WWAR EPHEMERA LABELS 1 EXTENDED LABELS

We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85 Ephemera Labels WWAR EPHEMERA LABELS 1 EXTENDED LABELS Larry Neal (Born 1937 in Atlanta; died 1981 in Hamilton, New York) “Any Day Now: Black Art and Black Liberation,” Ebony, August 1969 Jet, January 28, 1971 Printed magazines Collection of David Lusenhop During the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, publications marketed toward black audiences chronicled social, cultural, and political developments, covering issues of particular concern to their readership in depth. The activities and development of the Black Arts Movement can be traced through articles in Ebony, Black World, and Jet, among other publications; in them, artists documented the histories of their collectives and focused on the purposes and significance of art made by and for people of color. WWAR EPHEMERA LABELS 2 EXTENDED LABELS Weusi Group Portrait, early 1970s Photographic print Collection of Ronald Pyatt and Shelley Inniss This portrait of the Weusi collective was taken during the years in which Kay Brown was the sole female member. She is seated on the right in the middle row. WWAR EPHEMERA LABELS 3 EXTENDED LABELS First Group Showing: Works in Black and White, 1963 Printed book Collection of Emma Amos Jeanne Siegel (Born 1929 in United States; died 2013 in New York) “Why Spiral?,” Art News, September 1966 Facsimile of printed magazine Brooklyn Museum Library Spiral’s name, suggested by painter Hale Woodruff, referred to “a particular kind of spiral, the Archimedean one, because, from a starting point, it moves outward embracing all directions yet constantly upward.” Diverse in age, artistic styles, and interests, the artists in the group rarely agreed; they clashed on whether a black artist should be obliged to create political art. -

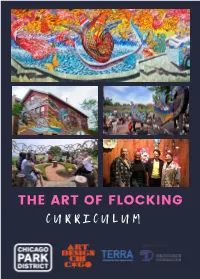

THE ART of FLOCKING CURRICULUM the Art of Flocking Curriculum

THE ART OF FLOCKING CURRICULUM The Art of Flocking Curriculum “There is an art to flocking: staying close enough not to crowd each other, aligned enough to maintain a shared direction, and cohesive enough to always move towards each other.” - adrienne maree brown The Art of Flocking: Cultural Stewardship in the Parks is a celebration of Chicago’s community-based art practices co-facilitated by the Chicago Park District and the Terra Foundation for American Art. A proud member of Art Design Chicago, this initiative aims to uplift Chicago artists with deep commitments to social justice, cultural preservation, community solidarity, and structural transformation. Throughout the summer of 2018, The Art of Flocking engaged 2,500 youth and families through 215 public programs and community exhibitions exploring the histories and legacies of Mexican-American public artist Hector Duarte and Sapphire and Crystals, Chicago's first and longest-standing Black women's artist collective.The Art of Flocking featured two beloved Chicago Park District programs: ArtSeed, designed to engage children ages 3 and up as well as their families and caretakers in 18 parks and playgrounds; and Young Cultural Stewards a multimedia youth fellowship centering young people ages 12–14 with regional hubs across the North, West, and South sides of Chicago. ArtSeed: Mobile Creative Play ArtSeed engages over 2,000 youth (ages 3-12) across 18 parks through storytelling, music, movement, and nature play rooted in neighborhood stories. Children explore the histories and legacies of Chicago's community-based artists and imagine creative solutions to challenges in their own neighborhoods. Teaching artists engage practice of social emotional learning, foundations in social justice, and trauma-informed pedagogy to cultivate children and families invested in fostering the cultural practices and creative capital of their parks and communities.