Time and the Image in the Armenian World: an Ethnography of Non-Recognition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

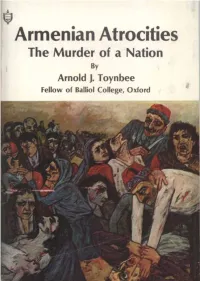

Armenian Atrocities the Murder of a Nation by Arnold J

Armenian Atrocities The Murder of a Nation By Arnold J. Toynbee Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford as . $315. R* f*4 p i,"'a p 7; mt & H ps4 & ‘ ' -it f, Armenian Atrocities: The Murder of a Nation By Arnold J. Toynbee Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford WITH A SPEECH DELIVERED BY LORD BRYCE IN THE HOUSE OF LORDS TANKIAN PUBLISHING CORPORATION -_NEW YORK MONTREAL LONDON Copyright © 1975 by Tankian Publishing Corp. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 75-10955 International Standard Book Number: 0-87899-005-4 First published in Great Britain by Hodder & Stoughton, 1917 First Tankian Publishing edition, 1975 Cover illustration: Original oil-painting by the renowned Franco-Armenian painter Zareh Mutafian, depicting the massacre of the Armenians by the Turks in 1915. TANKIAN TRADEMARK REG. U.S. PAT. OFF. AND FOREIGN COUNTRIES REGISTERED TRADEMARK - MARCA REGISTRADA PUBLISHED BY TANKIAN PUBLISHING CORP. G. P. O. BOX 678 -NEW YORK, N.Y. 10001 Printed in the United States of America DEDICATION 1915 - 1975 In commemoration of the 60th anniversary of the Armenian massacres by the Turks which commenced April 24, 1915, we dedicate the republication of this historical document to the memory of the almost 2,000,000 Armenian martyrs who perished during this great tragedy. A MAP displaying THE SCENE OF THE ATROCITIES P Boundaries of Regions thus =-:-- ‘\ s « summer RailtMys ThUS.... ...... .... |/i ; t 0 100 isouuts % «DAMAS CUQ BAGHDAQ - & Taterw A C*] \ C marked on this with the of twelve for such of the s Every place map, exception deported Armeninians as reached as them, as waiting- included in square brackets, has been the scene of either depor- places for death. -

Armenia and Georgia 9 Days / 8 Nights

Armenia and Georgia 9 days / 8 nights 2020 Dates 2020: April 10 – April 17 * Easter Holidays May 22 – May 29 June 26 – July 03 July 24 – July 31 August 07 – August 14 August 28 – September 04 October 16 – October 23 Itinerary: Day 1: Departure from your home country Day 2 : Yerevan city tour / Echmiadzin / Zvartnots Arrival early in the morning and transfer to your hotel for some rest. After breakfast meet your tour guide and start city tour around Yerevan. Drive to Echmiadzin – the place where the only Begotten descended. Holy Echmiadzin is the whole Armenians’ spiritual center and one of the centers of Christianity all over the world. They will participate in Sunday liturgy. Return to Yerevan with a stop at the ruins of Zvartnots temple - the pearl of the 7th century architecture, which is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage. Lunchtime. Visit Tsitsernakaberd-walking through Memorial park and visit museum of the victims of Genocide. Visit Cafesjian Show Room. Visit Vernisage flea market, the place to get a little taste of Armenia, to see the fusion between national traditions, art & crafts with contemporary taste. Overnight in Yerevan. (B/--/--) Day 3 : Yerevan / Khor Virap / Noravank /Yerevan Sightseeing tour to Khor-Virap monastery the importance of which is connected with Gregory the Illuminator, who introduced Christianity to Armenia. It is a wonderful masterpiece situated on top of a hill. It is a pilgrimage place where every year a lot of tourists and native people visit. It looks like a castle, where everybody has the hint to sit and dream while admiring the beauty of the church. -

12 Days Explore Turkey - Armenia - Georgia Tour

Full Itinerary & Trip Details 12 DAYS EXPLORE TURKEY - ARMENIA - GEORGIA TOUR Istanbul Tour - Bosphorus and Two Continents - Yerevan, Garni - Geghard, Khor Virap - Noravank - Areni - Selim - Sevan - Dilijan - Haghatsin - Alaverdi - Haghpat - Sanahin - Sadakhlo border - Tbilisi - Mtskheta - Gudauri - Kutaissi - Kutaisi and Gori PRICE STARTING FROM DURATION TOUR ID € 0 € 0 12 days 932 ITINERARY Day 1 : Istanbul - Arrival Day Meet at the Istanbul international Ataturk airport and transfer to your hotel. You will be given your room key and the rest of the day is yours to explore Istanbul. Overnight in Istanbul. Day 2 : Istanbul Tour Breakfast Included Guided Istanbul walking old city tour visiting Topkapi Palace (closed on tuesdays) Hippodrome, Blue Mosque, Aya Sophia Museum (closed on mondays), Underground Cistern, Covered Grand Bazaar (closed on sundays). Overnight in Istanbul. Day 3 : Bosphorus and Two Continents Breakfast Included Pick up at 08:30 from the hotel for the tour of Bosphorus and the Asian part of Istanbul. During the tour we will enjoy a Bosphorus Cruise, having lunch and visiting the Dolmabahce Palace, Bosphorus Bridge, Asian side.Overnight in Istanbul Day 4 : Istanbul - Yerevan - Armenia Breakfast, Lunch and Dinner Included After breakfast check out from the hotel and depart for Istanbul Ataturk International airport. Arrive to Yerevan and you will be transferred from airport to your hotel by one of official guide of Murti’s tour. Check into the hotel where your accommodation has been reserved for the night. You will be given your room key and the rest of the day is yours to enjoy party and explore to Yerevan. Day 5 : Garni - Geghard Breakfast, Lunch and Dinner Included After breakfast you will depart for a guided city tour Garni and Geghard. -

American University of Armenia the Impact Of

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF ARMENIA THE IMPACT OF DIASPORA AND DUAL CITIZENSHIP POLICY ON THE STATECRAFT PROCESS IN THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA A MASTER’S ESSAY SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS FOR PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY ARLETTE AVAKIAN YEREVAN, ARMENIA May 2008 SIGNATURE PAGE ___________________________________________________________________________ Faculty Advisor Date ___________________________________________________________________________ Dean Date AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF ARMENIA May 2008 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The work on my Master’s Essay was empowered and facilitated by the effort of several people. I would like to express my deep gratitude to my faculty adviser Mr. Vigen Sargsyan for his professional approach in advising and revising this Master’s Essay during the whole process of its development. Mr. Sargsyan’s high professional and human qualities were accompanying me along this way and helping me to finish the work I had undertaken. My special respect and appreciation to Dr. Lucig Danielian, Dean of School of Political Science and International Affairs, who had enormous impact on my professional development as a graduate student of AUA. I would like to thank all those organizations, political parties and individuals whom I benefited considerably. They greatly provided me with the information imperative for the realization of the goals of the study. Among them are the ROA Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Armenian Assembly of America Armenia Headquarter, Head Office of the Hay Dat (Armenian Cause) especially fruitful interview with the International Secretariat of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation Bureau in Yerevan, Tufenkian Foundation, Mr. Ralph Yirikyan, the General Manager of Viva Cell Company, Mr. -

The Shifting Geopolitics of the Black Sea Region

The Shifting Geopolitics of the Black Sea Region Actors, Drivers and Challenges Geir Flikke (ed.), Einar Wigen, Helge Blakkisrud and Pål Kolstø Norwegian Institute of International Affairs International of Institute Norwegian Institutt Utenrikspolitisk Norsk NUPI Report Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2011 ISBN: 978-82-7002-303-5 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. The text may not be printed in part or in full without the permission of the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 36 21 82 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 The Shifting Geopolitics of the Black Sea Region Actors, Drivers and Challenges Geir Flikke (ed.), Einar Wigen, Helge Blakkisrud and Pål Kolstø Introduction2 The Black Sea has long been a focal point for regionalization. Both the EU and NATO have had a proactive policy in the region, and various cooperative arrangements have been made to enhance multilateral mari- time governance in the Black Sea. Numerous regional mechanisms for interaction and cooperation among the littoral states have been set up, such as the Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC), the Black Sea Forum for Dialogue and Partnership (BSF) and the Black Sea Initiative of the EU (BSI). In January 2011, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on the Black Sea, reflecting the fact that since 2005 the region itself has entered a new modus operandi. -

The Armenian Robert L

JULY 26, 2014 MirTHErARoMENr IAN -Spe ctator Volume LXXXV, NO. 2, Issue 4345 $ 2.00 NEWS IN BRIEF The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 Armenia Inaugurates AREAL Linear Christians Flee Mosul en Masse Accelerator BAGHDAD (AP) — The message played array of other Sunni militants captured the a mobile number just in case we are offend - YEREVAN (Public Radio of Armenia) — The over loudspeakers gave the Christians of city on June 10 — the opening move in the ed by anybody,” Sahir Yahya, a Christian Advanced Research Electron Accelerator Iraq’s second-largest city until midday insurgents’ blitz across northern and west - and government employee from Mosul, said Laboratory (AREAL) linear accelerator was inau - Saturday to make a choice: convert to ern Iraq. As a religious minority, Christians Saturday. “This changed two days ago. The gurated this week at the Center for Islam, pay a tax or face death. were wary of how they would be treated by Islamic State people revealed their true sav - the Advancement of Natural Discoveries By the time the deadline imposed by the hardline Islamic militants. age nature and intention.” using Light Emission (CANDLE) Synchrotron Islamic State extremist group expired, the Yahya fled with her husband and two Research Institute in Yerevan. vast majority of Christians in Mosul had sons on Friday morning to the town of The modern accelerator is an exceptional and made their decision. They fled. Qaraqoush, where they have found tempo - huge asset, CANDLE’s Executive Director Vasily They clambered into cars — children, par - Most of Mosul’s remaining Christians rary lodging at a monastery. -

Georgia Armenia Azerbaijan 4

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 317 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travell ers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well- travell ed team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to postal submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/privacy. Stefaniuk, Farid Subhanverdiyev, Valeria OUR READERS Many thanks to the travellers who used Superno Falco, Laurel Sutherland, Andreas the last edition and wrote to us with Sveen Bjørnstad, Trevor Sze, Ann Tulloh, helpful hints, useful advice and interest- Gerbert Van Loenen, Martin Van Der Brugge, ing anecdotes: Robert Van Voorden, Wouter Van Vliet, Michael Weilguni, Arlo Werkhoven, Barbara Grzegorz, Julian, Wojciech, Ashley Adrian, Yoshida, Ian Young, Anne Zouridakis. Asli Akarsakarya, Simone -

Glendale Exhibits Explore Concept of Inherited Trauma of Armenian Genocide

MARCH 24, 2018 Mirror-SpeTHE ARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXVIII, NO. 35, Issue 4530 $ 2.00 NEWS The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 INBRIEF Washington Armenian Aliyev Insists on Community Unites in ‘Historic Azeri Lands’ Support of Artsakh In Armenia BAKU (RFE/RL) — Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev has stood by his claims that much of By Aram Arkun modern-day Armenia lies in “historic Azerbaijani Mirror-Spectator Staff lands.” “I have repeatedly said and want to say once again that the territory of contemporary Armenia WASHINGTON — Upon the initiative of is historic Azerbaijani lands. There are numerous the representation of Artsakh in the United books and maps confirming that,” Aliyev said on States, the Armenian Assembly of America Monday, March 19, at the start of official celebra- and the Armenian National Committee of tions of Nowruz, the ancient Persian New Year America (ANCA) organized a reception and marked as a public holiday in Azerbaijan. banquet for the Armenian community on “The Azerbaijani youth must know this first and March 17 at the University Club in foremost. Let it know that most of modern-day Washington D. C. to honor the visiting del- Armenia is historic Azerbaijani lands. We will egation of the Republic of Artsakh led by never forget this,” he said. President Bako Sahakyan. Aliyev has repeatedly made such statements, The bilingual event was moderated by Annie Totah receives a medal from President Bako Sahakyan, while Aram Hamparian holds the medal he just got (photo: Aram Arkun) most recently on February 8. Speaking at a pre- Annie Simonian Totah, board member of election congress of his Yeni Azerbaycan party, he the Armenian Assembly, and Aram pledged to “return Azerbaijanis” to Yerevan, Hamparian, executive director of the two Armenian lobbying organizations of pointed out that the ANCA and the Syunik province and the area around Lake Sevan. -

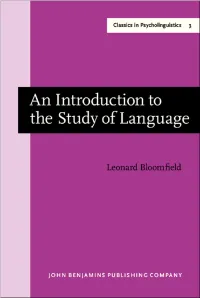

An Introduction to the Study of Language LEONARD BLOOMFIELD

INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY OF LANGUAGE AMSTERDAM STUDIES IN THE THEORY AND HISTORY OF LINGUISTIC SCIENCE General Editor E.F. KONRAD KOERNER (University of Ottawa) Series II - CLASSICS IN PSYCHOLINGUISTICS Advisory Editorial Board Ursula Bellugi (San Diego);John B. Carroll Chapel Hill, N.C.) Robert Grieve (Perth, W.Australia);Hans Hormann (Bochum) John C. Marshall (Oxford);Tatiana Slama-Cazacu (Bucharest) Dan I. Slobin (Berkeley) Volume 3 Leonard Bloomfield An Introduction to the Study of Language LEONARD BLOOMFIELD AN INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY OF LANGUAGE New edition with an introduction by JOSEPH F. KESS University of Victoria Victoria, British Columbia JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY AMSTERDAM/PHILADELPHIA 1983 FOR CHARLES F. HOCKETT © Copyright 1983 - John Benjamins B.V. ISSN 0165 716X ISBN 90 272 1892 7 (Pp.) / ISBN 90 272 1891 9(Hb.) No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. ACKNOWLEDGMENT For permission to reprint Leonard Bloomfield's book, An Introduction to the Study of Language (New York, 1914) I would like to thank the publisher Holt, Rinehart & Winston, and Ms Mary McGowan, Manager, Rights and Permissions Department.* Thanks are also due to my colleague and friend Joseph F. Kess for having con• tributed an introductory article to the present reprinting of Bloomfield's first book, and to Charles F. Hockett of Cornell University, for commenting on an earlier draft of my Foreword, suggesting substantial revisions of content and form. It is in recognition of his important contribution to a re-evaluation of Bloomfield's oeuvre that the present volume is dedicated to him. -

Buradan Yönetildiği Ile Ilgili Bir Kanı Vardır

ERMENİ ARAŞTIRMALARI Dört Aylık Tarih, Politika ve Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi sayı Olaylar ve Yorumlar 45 Ömer E. LÜTEM 2013 Ermenistan-Azerbaycan Çatışmasının Yakın Geleceği: Barış mı? Savaş mı? Yoksa Ateşkes mi? Emin ŞIHALIYEV İngiltere’nin Kafkasya Politikası ve Ermeni Sorunu (1917-1918) Tolga BAŞAK Levon Ter Petrosyan’ın “XII. ve XIII. Yüzyılda Kilikya Ermenileri Kültüründe Asurilerin Rolü” Adlı Eserinde Süryani-Ermeni İlişkileri Yıldız Deveci BOZKUŞ Ermeni Siyasal Düşüncesinde Terörizm Hatem CABBARLI Türkiye’nin Dış Politikasına Etkisi Bakımından 2015’e Doğru Ermeni Lobisi Ömer Faruk AN KİTAP ÖZETİ GÜNCEL BELGELER ERMENİ ARAŞTIRMALARI Dört Aylık, Tarih, Politika ve Uluslararası İlişkiler Dergisi 2013, Sayı 45 YAYIN SAHİBİ Ali Kenan ERBULAN SORUMLU YAZI İŞLERİ MÜDÜRÜ Aslan Yavuz ŞİR YAZI KURULU Alfabetik Sıra İle Prof. Dr. Kemal ÇİÇEK Prof. Dr. Bayram KODAMAN (Türk Tarih Kurumu, (Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi) Karadeniz Teknik Üniversitesi) Prof. Dr. Enver KONUKÇU Dr. Şükrü ELEKDAĞ Doç. Dr. Erol KÜRKÇÜOĞLU (Milletvekili, E. Büyükelçi) (Türk-Ermeni İlişkileri Araştırma Prof. Dr. Temuçin Faik ERTAN Merkezi Müdürü, Atatürk Üniversitesi) (Ankara Üniversitesi) Prof. Dr. Nurşen MAZICI Prof. Dr. Yusuf HALAÇOĞLU (Marmara Üniversitesi) (Gazi Üniversitesi) Prof. Dr. Hikmet ÖZDEMİR Dr. Erdal İLTER (Siyaset Bilimci) (Tarihçi, Yazar) Prof. Dr. Mehmet SARAY Dr. Yaşar KALAFAT (Tarihçi) (Tarihçi, Yazar) Dr. Bilal ŞİMŞİR Doç. Dr. Davut KILIÇ (E. Büyükelçi, Tarihçi) (Fırat Üniversitesi) Pulat TACAR (E. Büyükelçi) DANIŞMA KURULU Alfabetik Sıra İle Prof. Dr. Dursun Ali AKBULUT Prof. Dr. Nuri KÖSTÜKLÜ (Ondokuz Mayıs Üniversitesi) (Selçuk Üniversitesi) Yrd. Doç. Dr. Kalerya BELOVA Andrew MANGO (Uluslararası İlişkiler Enstitüsü) (Gazeteci, Yazar) Prof. Dr. Salim CÖHCE Prof. Dr. Justin MCCARTHY (İnönü Üniversitesi) (Louisville Üniversitesi) Edward ERICKSON Prof. -

THE ARMENIAN Mirrorc SPECTATOR Since 1932

THE ARMENIAN MIRRORc SPECTATOR Since 1932 Volume LXXXXI, NO. 42, Issue 4684 MAY 8, 2021 $2.00 Rep. Kazarian Is Artsakh Toun Proposes Housing Solution Passionate about For 2020 Artsakh War Refugees Public Service By Harry Kezelian By Aram Arkun Mirror-Spectator Staff Mirror-Spectator Staff EAST PROVIDENCE, R.I. — BRUSSELS — One of the major results Katherine Kazarian was elected of the Artsakh War of 2020, along with the Majority Whip of the Rhode Island loss of territory in Artsakh, is the dislocation State House in January, but she’s no of tens of thousands of Armenians who have stranger to politics. The 30-year-old lost their homes. Their ability to remain in Rhode Island native was first elected Artsakh is in question and the time remain- to the legislative body 8 years ago ing to solve this problem is limited. Artsakh straight out of college at age 22. Toun is a project which offers a solution. Kazarian is a fighter for her home- The approach was developed by four peo- town of East Providence and her Ar- ple, architects and menian community in Rhode Island urban planners and around the world. And despite Movses Der Kev- the partisan rancor of the last several orkian and Sevag years, she still loves politics. Asryan, project “It’s awesome, it’s a lot of work, manager and co- but I do love the job. And we have ordinator Grego- a great new leadership team at the ry Guerguerian, in urban planning, architecture, renovation Khanumyan estimated that there are State House.” and businessman and construction site management in Arme- around 40,000 displaced people willing to Kazarian was unanimously elect- and philanthropist nia, Belgium and Lebanon. -

Journal of Language Relationship

Российский государственный гуманитарный университет Russian State University for the Humanities Russian State University for the Humanities Institute of Linguistics of the Russian Academy of Sciences Journal of Language Relationship International Scientific Periodical Nº 3 (16) Moscow 2018 Российский государственный гуманитарный университет Институт языкознания Российской Академии наук Вопросы языкового родства Международный научный журнал № 3 (16) Москва 2018 Advisory Board: H. EICHNER (Vienna) / Chairman W. BAXTER (Ann Arbor, Michigan) V. BLAŽEK (Brno) M. GELL-MANN (Santa Fe, New Mexico) L. HYMAN (Berkeley) F. KORTLANDT (Leiden) A. LUBOTSKY (Leiden) J. P. MALLORY (Belfast) A. YU. MILITAREV (Moscow) V. F. VYDRIN (Paris) Editorial Staff: V. A. DYBO (Editor-in-Chief) G. S. STAROSTIN (Managing Editor) T. A. MIKHAILOVA (Editorial Secretary) A. V. DYBO S. V. KULLANDA M. A. MOLINA M. N. SAENKO I. S. YAKUBOVICH Founded by Kirill BABAEV © Russian State University for the Humanities, 2018 Редакционный совет: Х. АЙХНЕР (Вена) / председатель В. БЛАЖЕК (Брно) У. БЭКСТЕР (Анн Арбор) В. Ф. ВЫДРИН (Париж) М. ГЕЛЛ-МАНН (Санта-Фе) Ф. КОРТЛАНДТ (Лейден) А. ЛУБОЦКИЙ (Лейден) Дж. МЭЛЛОРИ (Белфаст) А. Ю. МИЛИТАРЕВ (Москва) Л. ХАЙМАН (Беркли) Редакционная коллегия: В. А. ДЫБО (главный редактор) Г. С. СТАРОСТИН (заместитель главного редактора) Т. А. МИХАЙЛОВА (ответственный секретарь) А. В. ДЫБО С. В. КУЛЛАНДА М. А. МОЛИНА М. Н. САЕНКО И. С. ЯКУБОВИЧ Журнал основан К. В. БАБАЕВЫМ © Российский государственный гуманитарный университет, 2018 Вопросы языкового родства: Международный научный журнал / Рос. гос. гуманитар. ун-т; Рос. акад. наук. Ин-т языкознания; под ред. В. А. Дыбо. ― М., 2018. ― № 3 (16). ― x + 78 с. Journal of Language Relationship: International Scientific Periodical / Russian State Uni- versity for the Humanities; Russian Academy of Sciences.