Draughtsman Engineers Serving the Spanish Monarchy in the Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programa 337A Administración Del Patrimonio Histórico

PROGRAMA 337A ADMINISTRACIÓN DEL PATRIMONIO HISTÓRICO NACIONAL 1. DESCRIPCIÓN Los objetivos y las actuaciones básicas del Consejo de Administración del Patrimonio Nacional para el ejercicio 2014, al igual que en los anteriores, vienen determinados por su propia Ley 23/1982, de 16 de junio, Reguladora del Patrimonio Nacional y por su Reglamento, aprobado por Real Decreto 496/1987, de 18 de marzo, modificado por los Reales Decretos 694/1989, de 16 de junio, 2208/1995, de 28 de diciembre, y 600/2011, de 29 de abril, que ha modificado la estructura orgánica del Organismo, en lo referente a las Unidades dependientes de la Gerencia. De acuerdo con lo previsto en el artículo primero de la Ley 23/1982, son fines del Consejo de Administración del Patrimonio Nacional la gestión y administración de los bienes y derechos del Patrimonio Nacional. En virtud del artículo segundo de dicha Ley, tienen la calificación jurídica de bienes del Patrimonio Nacional los de titularidad del Estado afectados al uso y servicio del Rey y de los miembros de la Familia Real para el ejercicio de la alta representación que la Constitución y las leyes les atribuyen. Además se integran en el citado Patrimonio los derechos y cargas de Patronato sobre las Fundaciones y Reales Patronatos a que se refiere la citada Ley. Y conforme prevé el artículo tercero de la Ley 23/1982, en cuanto sea compatible con la afectación de los bienes del Patrimonio Nacional, a la que se refiere el artículo anterior, el Consejo de Administración adoptará las medidas conducentes al uso de los mismos con fines culturales, científicos y docentes. -

Catalogue Summer 2012

JONATHAN POTTER ANTIQUE MAPS CATALOGUE SUMMER 2012 INTRODUCTION 2012 was always going to be an exciting year in London and Britain with the long- anticipated Queen’s Jubilee celebrations and the holding of the Olympic Games. To add to this, Jonathan Potter Ltd has moved to new gallery premises in Marylebone, one of the most pleasant parts of central London. After nearly 35 years in Mayfair, the move north of Oxford Street seemed a huge step to take, but is only a few minutes’ walk from Bond Street. 52a George Street is set in an attractive area of good hotels and restaurants, fine Georgian residential properties and interesting retail outlets. Come and visit us. Our summer catalogue features a fascinating mixture of over 100 interesting, rare and decorative maps covering a period of almost five hundred years. From the fifteenth century incunable woodcut map of the ancient world from Schedels’ ‘Chronicarum...’ to decorative 1960s maps of the French wine regions, the range of maps available to collectors and enthusiasts whether for study or just decoration is apparent. Although the majority of maps fall within the ‘traditional’ definition of antique, we have included a number of twentieth and late ninteenth century publications – a significant period in history and cartography which we find fascinating and in which we are seeing a growing level of interest and appreciation. AN ILLUSTRATED SELECTION OF ANTIQUE MAPS, ATLASES, CHARTS AND PLANS AVAILABLE FROM We hope you find the catalogue interesting and please, if you don’t find what you are looking for, ask us - we have many, many more maps in stock, on our website and in the JONATHAN POTTER LIMITED gallery. -

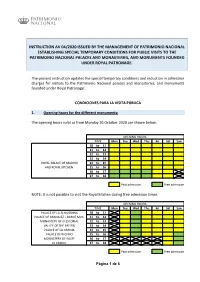

Instruction Av 04/2020 Issued by the Management Of

INSTRUCTION AV 04/2020 ISSUED BY THE MANAGEMENT OF PATRIMONIO NACIONAL ESTABLISHING SPECIAL TEMPORARY CONDITIONS FOR PUBLIC VISITS TO THE PATRIMONIO NACIONAL PALACES AND MONASTERIES, AND MONUMENTS FOUNDED UNDER ROYAL PATRONAGE. The present instruction updates the special temporary conditions and reduction in admission charges for visitors to the Patrimonio Nacional palaces and monasteries, and monuments founded under Royal Patronage: CONDICIONES PARA LA VISITA PÚBLICA 1. Opening hours for the different monuments: The opening hours valid as from Monday 26 October 2020 are shown below: OPENING HOURS TIME Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 10 to 11 11 to 12 12 to 13 13 to 14 ROYAL PALACE OF MADRID 14 to 15 AND ROYAL KITCHEN 15 to 16 16 to 17 17 to 18 Paid admission Free admission NOTE: It is not possible to visit the Royal Kitchen during free admission times. OPENING HOURS TIME Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun PALACE OF LA ALMUDAINA 10 to 11 PALACE OF ARANJUEZ + BARGE MUS. 11 to 12 MONASTERY OF El ESCORIAL 12 to 13 VALLEY OF THE FALLEN 13 to 14 PALACE OF LA GRANJA 14 to 15 PALACE OF RIOFRIO 15 to 16 MONASTERY OF YUSTE 16 to 17 EL PARDO 17 to 18 Paid admission Free admission Página 1 de 6 OPENING HOURS TIME Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 10:00 to 10:30 10:30 to 11 11 to 12 12 to 13 CONVENT OF SANTA MARIA LA REAL HUELGAS 13 to 14 14 to 15 CONVENT OF SANTA CLARA TORDESILLAS 15 to 16 16 to 17 17 to 18 18 to 18:30 Paid admission Free admission The Casas del Príncipe (at El Pardo and El Escorial), Casa del Infante (at El Escorial) and Casa del Labrador (at Aranjuez) will not be open. -

Aproximacions a La Història De La Cartografia

Aquest llibre recull les ponències presentades a les Aproximacions Jornades d’història de la cartografi a de Barcelona, celebra- des els dies 19 i 20 de maig de 2010 a la Casa de l’Ar- a la història diaca, com a fruit de la col·laboració entre l’Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona i l’Institut Carto- de la cartografi a gràfi c de Catalunya. La intervenció de deu especialis- tes de procedència diferent –arquitectura, ciències de Barcelona físiques, geografi a i història– ha permès d’aprofun- dir en diferents aspectes del patrimoni cartogràfi c de Barcelona, acumulat des del segle XVI fi ns al segle XX. Hi és abordat el canviant procés d’elaboració dels Carme Montaner mapes (rerefons científi c, tècniques d’aixecament i Francesc Nadal d’edició, natura dels organismes implicats, persona- (editors) litat dels cartògrafs) d’acord amb un punt de vista que subratlla, d’una banda, que els resultats varien segons les motivacions –militars, fi scals, urbanísti- ques, etc.– i, de l’altra, que la interrelació d’aquestes diferents visions és la clau d’un progrés històric fi - nalment compartit. a de Barcelona Aproximacions a la història a la història Aproximacions de la cartografi 1 2 Aproximacions a la història de la cartografi a de Barcelona 3 Institut de Cultura CONSELL D’ADMINISTRACIÓ Generalitat Director Editen de l’Ajuntament de Catalunya. Jaume Miranda i Canals Ajuntament de Barcelona Presidenta Institut Cartogràfi c de de Barcelona Ima. Sra. Inmaculada Moraleda Departament Subdirector general tècnic Catalunya i Pérez de Política Territorial Josep Lluís Colomer i Alberich i Obres Públiques. -

Museológica: Tendencias E Diccionario Deldibujoylaestampa Instrumentos Léxicosdeinterés,Comoel Definitiva

ARTE GRÁFICO Y LENGUAJE1 Javier Blas José Manuel Matilla Calcografía Nacional Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando tendencias l empleo de una terminología adecuada relativa al arte gráfico no es una E cuestión irrelevante para el profesional de museos. Precisar el uso de las palabras que integran el vocabulario técnico de la estampa, es decir, atender a su valor semántico, no es sólo una necesidad sino también una exigencia por sus implicaciones en la valoración social museológica: del grabado y procedimientos afines. El debate sobre el vocabulario del arte gráfico sigue abierto, ya que la normalización lingüística en este campo del conocimiento aún no ha sido presentada de manera definitiva. No obstante, hoy se dispone de instrumentos léxicos de interés, como el Diccionario del dibujo y la estampa2, cuyos Lámina. Entintado de la lámina planteamientos ofrecen una línea argumental Francisco de Goya, Volaverunt razonada y son la expresión de una tendencia en el uso de la terminología avalada por las fuentes históricas. Al margen del modelo que propone ese repertorio, cualquier otra alter- nativa de normalización podría ser aceptable. Lo que no resulta admisible es la dispersión de criterios para la definición de idénticos procesos y productos gráficos. 122 museológica. tendencias El uso indebido del lenguaje ha Precisar el uso de las Directamente relacionada con la perpetuado algunas conductas poco citada jerarquía de los medios afortunadas, entre ellas la igualación palabras que integran gráficos se encuentra una cuarta del campo semántico en significantes el vocavulario técnico constatación: el menosprecio genera- de muy distinta procedencia histórica lizado hacia las técnicas introducidas y etimológica. -

Engineers of the Renaissance

Bertrand Gille Engineers of the Renaissance . II IIIII The M.I.T.Press Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts ' ... � {' ( l..-'1 b 1:-' TA18 .G!41J 1966 METtTLIBRARY En&Jneersor theRenaissance. 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 0020119043 Copyright @ 1966 by Hermann, Paris Translated from Les ingenieurs de la Renaissance published by Hermann, Paris, in 1964 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 66-27213 Printed in Great Britain Contents List of illustrations page 6 Preface 9 Chapter I The Weight of Tradition 15 2 The Weight of Civilization 3 5 3 The German School 55 4 The First Italian Generation 79 5 Francesco di Giorgio Martini 101 Cj 6 An Engineer's Career -Leonardo da Vinci 121 "'"" f:) 7 Leonardo da Vinci- Technician 143 ��"'t�; 8 Essay on Leonardo da Vinci's Method 171 �� w·· Research and Reality ' ·· 9 191 �' ll:"'t"- 10 The New Science 217 '"i ...........,_ .;::,. Conclusion 240 -... " Q: \.., Bibliography 242 �'� :::.(' Catalogue of Manuscripts 247 0 " .:; Index 254 � \j B- 13 da Page Leonardo Vinci: study of workers' positions. List of illustrations 18 Apollodorus ofDamascus: scaling machine. Apollodorus of Damascus: apparatus for pouring boiling liquid over ramparts. 19 Apollodorus ofDamascus: observation platform with protective shield. Apollodorus of Damascus: cover of a tortoise. Apollodorus ofDamascus: fire lit in a wall andfanned from a distance by bellows with a long nozzle. 20 Hero of Byzantium: assault tower. 21 Hero of :Byzantium: cover of a tortoise. 24 Villard de Honnecourt: hydraulic saw; 25 Villard de Honnecourt: pile saw. Villard de Honnecourt: screw-jack. , 26 Villard de Honnecourt: trebuchet. Villard de Honnecourt: mechanism of mobile angel. -

A Renaissance Depiction of a Tornado

A RENAISSANCE DEPICTION OF A TORNADO BY KLAUS P. HOINKA AND MANUEL DE CASTRO A Flemish tapestry demonstrates how weather in sixteenth-century art can be of testimonial, decorative, or emblematic character. uring the Renaissance (1400–1600) meteorologi- discoveries of new lands and seas, which consider- cal phenomena attracted the interest of dil- ably enlarged and widened old ideas and concep- D etantes and artists. Interest in the weather ex- tions. Atmospheric phenomena never seen before pressed itself in the form of individual weather notes were identified by Western explorers, and climates (see Hellman 1901), the first serious attempts to pro- that were very different from those at home became vide some rules for predicting the weather (Hellmann known (Hellmann 1908). Among these new me- 1915, 1924a), and the well-established astrometeo- teorological phenomena, tornadoes and waterspouts rological approaches to forecasting the weather. The provoked considerable interest due to their damaging Renaissance period saw increasing attention toward effects, as well as their beauty. For centuries, the con- meteorological observations, in comparison to the cept of tornadoes was indistinguishable from people’s preceeding centuries where meteorology was domi- notions of other windstorms. The word “tornado” nated by Aristotle’s “Meteorologica” (3400 b.c.). The had an archaic meaning concerning variable, gusty invention of quantitative measuring devices, such as winds and rain, and, perhaps, thunderstorms near the thermometer (in 1607) and the barometer (1643), the equator. was yet to come. The Oxford English Dictionary (1989) defines a The fresh stimulus for weather observations came tornado in the following way: “In the 16th century at the end of the fifteenth century from the great navigators called a tornado (or ternado) a violent thunderstorm of the tropical Atlantic, with torren- tial rain, and often with sudden and violent gusts of AFFILIATIONS: HOINKA—Institut für Physik der Atmosphäre, wind . -

Map As Tapestry: Science and Art in Pedro Teixeira's 1656 Representation of Madrid

The Art Bulletin ISSN: 0004-3079 (Print) 1559-6478 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 Map as Tapestry: Science and Art in Pedro Teixeira's 1656 Representation of Madrid Jesús Escobar To cite this article: Jesús Escobar (2014) Map as Tapestry: Science and Art in Pedro Teixeira's 1656 Representation of Madrid, The Art Bulletin, 96:1, 50-69, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.2014.877305 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2014.877305 Published online: 25 Apr 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 189 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcab20 Download by: [Northwestern University] Date: 22 September 2016, At: 08:04 Map as Tapestry: Science and Art in Pedro Teixeira’s 1656 Representation of Madrid Jesus Escobar “Mantua of the Carpentana, or Madrid, Royal City” reads the attributed to the overreach of Philip IV’s royal favorite and Latin inscription on the banderole that hovers above Pedro prime minister, Gaspar de Guzman, the count-duke of Teixeira’s monumental map of the Spanish capital, the Topo- Olivares (1587–1645). In 1640, in the midst of the Thirty graphia de la Villa de Madrid (Topography of the town of Years’ War, rebellions arose in Catalonia and Portugal, com- Madrid) (Fig. 1). The text refers to a place from the distant pounding the monarchy’s ongoing financial crises and lead- Roman past, the purported origin of Madrid, as well as the ing to Olivares’s ouster. -

Estudios Sobre Guerra Y Sociedad En La Monarquía Hispánica

ESTUDIOS SOBRE GUERRA Y SOCIEDAD EN LA MONARQUÍA HISPÁNICA Guerra marítima, estrategia, organización y cultura militar (1500-1700) Enrique García Hernán y Davide Maffi (Eds.) Historia de España y su proyección internacional XI Colección dirigida por Enrique García Hernán Estudios sobre guerra y sociedad en la Monarquía Hispánica : guerra marítima, estrategia, organización y cultura militar (1500-1700) / Enrique García Hernán y Davide Maffi (eds.) — Valencia : Albatros, D.L. V. 172-2017. — 943 p.: il. col.; 17 x 24 cm . — (Historia de España y su proyección internacional; 11) Incluye referencias bibliográficas e índice. ISBN: 978-84-7274-328-1. Depósito Legal: V. 172 - 2017. I. García Hernán, Enrique (1964-), ed. II. Maffi, Davide, ed. III. Serie. 1. Potencia marítima — España — 1500-1700. 2. España — Historia — 1500-1700. 3. América española. 94:355(460+7/8=134)”15/16”(082) La presente obra se ha realizado en el marco de los Proyectos de Investigación de I+D MINECO HAR2012-36884-C01-C02 (IP Enrique García Hernán y Óscar Recio Morales) y de los Proyectos HAR2015-64574-C2-1-P y C2-2-P (IP Óscar Recio Morales y José Cutillas Ferrer). Comité Científico Asesor de este volumen: Prof. Beatrice Heuser (Profesora de Política y Relaciones Internaciones, Universidad de Reading) Prof. Agustín González Enciso (Profesor de Historia Económica, Universidad de Navarra) Dr. Óscar Recio Morales (Profesor de Historia Moderna, Universidad Complutense de Madrid) Dr. Ismael Jiménez Jiménez (Departamento de Historia de América, Universidad de Sevilla) Dr. Antonio Jiménez Estrella (Profesor de Historia Moderna y de América, Universidad de Granada) Dra. Valentina Favarò (Profesora del Departamento de Cultura y Sociedad, Universidad de Palermo) Los capítulos de este libro han pasado por una evaluación peer review. -

Europa Regina. 16Th Century Maps of Europe in the Form of a Queen Europa Regina

Belgeo Revue belge de géographie 3-4 | 2008 Formatting Europe – Mapping a Continent Europa Regina. 16th century maps of Europe in the form of a queen Europa Regina. Cartes d’Europe du XVIe siècle en forme de reine Peter Meurer Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/belgeo/7711 DOI: 10.4000/belgeo.7711 ISSN: 2294-9135 Publisher: National Committee of Geography of Belgium, Société Royale Belge de Géographie Printed version Date of publication: 31 December 2008 Number of pages: 355-370 ISSN: 1377-2368 Electronic reference Peter Meurer, “Europa Regina. 16th century maps of Europe in the form of a queen”, Belgeo [Online], 3-4 | 2008, Online since 22 May 2013, connection on 05 February 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/belgeo/7711 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/belgeo.7711 This text was automatically generated on 5 February 2021. Belgeo est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Europa Regina. 16th century maps of Europe in the form of a queen 1 Europa Regina. 16th century maps of Europe in the form of a queen Europa Regina. Cartes d’Europe du XVIe siècle en forme de reine Peter Meurer 1 The most common version of the antique myth around the female figure Europa is that which is told in book II of the Metamorphoses (“Transformations”, written around 8 BC) by the Roman poet Ovid : Europa was a Phoenician princess who was abducted by the enamoured Zeus in the form of a white bull and carried away to Crete, where she became the first queen of that island and the mother of the legendary king Minos. -

Violence, Protection and Commerce

This file is to be used only for a purpose specified by Palgrave Macmillan, such as checking proofs, preparing an index, reviewing, endorsing or planning coursework/other institutional needs. You may store and print the file and share it with others helping you with the specified purpose, but under no circumstances may the file be distributed or otherwise made accessible to any other third parties without the express prior permission of Palgrave Macmillan. Please contact [email protected] if you have any queries regarding use of the file. Proof 1 2 3 3 4 Violence, Protection and 5 6 Commerce 7 8 Corsairing and ars piratica in the Early Modern 9 Mediterranean 10 11 Wolfgang Kaiser and Guillaume Calafat 12 13 14 15 Like other maritime spaces, and indeed even large oceans such as the 16 Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean was not at all a ‘no man’s sea’ – as 17 the sea in general appears, opposed to territorial conquest and occupa- 18 tion of land, in a prominent way in Carl Schmitt’s opposition between 19 a terrestrian and a ‘free maritime’ spatial order.1 Large oceanic spaces 20 such as the Indian Ocean and smaller ones such as the Mediterranean 21 were both culturally highly saturated and legally regulated spaces.2 22 The Inner Sea has even been considered as a matrix of the legal and 23 political scenario of imposition of the Roman ‘policy of the sea’ that 24 had efficiently guaranteed free circulation and trade by eliminating 25 the pirates – Cicero’s ‘enemy of mankind’ 3– who formerly had infected the 26 Mediterranean. -

Contributions of the Ottoman Empire to the Construction of Modern Europe

CONTRIBUTIONS OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE TO THE CONSTRUCTION OF MODERN EUROPE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY MUSTAFA SERDAR PALABIYIK IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS JUNE 2005 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Sencer Ayata Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science/Arts / Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Atilla Eralp Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science/Arts/Doctor of Philosophy. Assoc. Prof. Dr. A. Nuri Yurdusev Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Bağcı (METU, IR) Assoc. Prof. Dr. A. Nuri Yurdusev (METU, IR) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ömer Turan (METU, HIST) ii I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last Name: Mustafa Serdar PALABIYIK Signature: iii ABSTRACT CONTRIBUTIONS OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE TO THE CONSTRUCTION OF MODERN EUROPE Palabıyık, Mustafa Serdar M.Sc., Department of International Relations Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. A. Nuri Yurdusev June 2003, 159 pages This thesis aims to analyze the contributions of the Ottoman Empire to the construction of modern Europe in the early modern period.