Map As Tapestry: Science and Art in Pedro Teixeira's 1656 Representation of Madrid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Instruction Av 04/2020 Issued by the Management Of

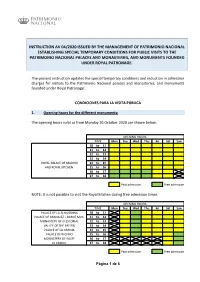

INSTRUCTION AV 04/2020 ISSUED BY THE MANAGEMENT OF PATRIMONIO NACIONAL ESTABLISHING SPECIAL TEMPORARY CONDITIONS FOR PUBLIC VISITS TO THE PATRIMONIO NACIONAL PALACES AND MONASTERIES, AND MONUMENTS FOUNDED UNDER ROYAL PATRONAGE. The present instruction updates the special temporary conditions and reduction in admission charges for visitors to the Patrimonio Nacional palaces and monasteries, and monuments founded under Royal Patronage: CONDICIONES PARA LA VISITA PÚBLICA 1. Opening hours for the different monuments: The opening hours valid as from Monday 26 October 2020 are shown below: OPENING HOURS TIME Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 10 to 11 11 to 12 12 to 13 13 to 14 ROYAL PALACE OF MADRID 14 to 15 AND ROYAL KITCHEN 15 to 16 16 to 17 17 to 18 Paid admission Free admission NOTE: It is not possible to visit the Royal Kitchen during free admission times. OPENING HOURS TIME Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun PALACE OF LA ALMUDAINA 10 to 11 PALACE OF ARANJUEZ + BARGE MUS. 11 to 12 MONASTERY OF El ESCORIAL 12 to 13 VALLEY OF THE FALLEN 13 to 14 PALACE OF LA GRANJA 14 to 15 PALACE OF RIOFRIO 15 to 16 MONASTERY OF YUSTE 16 to 17 EL PARDO 17 to 18 Paid admission Free admission Página 1 de 6 OPENING HOURS TIME Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 10:00 to 10:30 10:30 to 11 11 to 12 12 to 13 CONVENT OF SANTA MARIA LA REAL HUELGAS 13 to 14 14 to 15 CONVENT OF SANTA CLARA TORDESILLAS 15 to 16 16 to 17 17 to 18 18 to 18:30 Paid admission Free admission The Casas del Príncipe (at El Pardo and El Escorial), Casa del Infante (at El Escorial) and Casa del Labrador (at Aranjuez) will not be open. -

Proquest Dissertations

THE RISE OF THE COURTIER-ARTIST: THE POLITICAL CAREERS OF PETER PAUL RUBENS AND DIEGO VELAZQUEZ IN PHILIP IV'S SPAIN A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Guelph by NICOLE GRIEVE In partial fulfillment of requirements For the degree of Master of Arts January, 2008 © Nicole Grieve, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-41824-6 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-41824-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

BROCHURE-ARRE-2011-UK:Mise En Page 1

Discovering European Heritage in Royal Residences Association of European Royal Residences Contents 3 The Association of European Royal Residences 4 National Estate of Chambord, France 5 Coudenberg - Former Palace of Brussels, Belgium 6 Wilanow Palace Museum, Poland 7 Palaces of Versailles and the Trianon, France 8 Schönbrunn Palace, Austria 9 Patrimonio Nacional, Spain 10 Royal Palace of Gödöllo”, Hungary 11 Royal Residences of Turin and of the Piedmont, Italy 12 Mafra National Palace, Portugal 13 Hampton Court Palace, United Kingdom 14 Peterhof Museum, Russia 15 Royal Palace of Caserta, Italy 16 Prussian Palaces and Gardens of Berlin-Brandenburg, Germany 17 Royal Palace of Stockholm, Sweden 18 Rosenborg Castle, Denmark 19 Het Loo Palace, Netherlands Cover: Chambord Castle. North facade © LSD ● F. Lorent, View from the park of the ruins of the former Court of Brussels, watercolour, 18th century © Brussels, Maison du Roi - Brussels City Museums ● Wilanow Palace Museum ● Palace of Versailles. South flowerbed © château de Versailles-C. Milet ● The central section of the palace showing the perron leading up to the Great Gallery, with the Gloriette in the background © Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H., Vienna ● Real Sitio de La Granja de San Ildefonso © Patrimonio Nacional ● View from the garden © Gödöllo “i Királyi Kastély ● The Margaria © Racconigi ● Venaria Reale. View of the Palace © Venaria Reale ● Mafra National Palace. Photo S. Medeiros © Palacio de Mafra ● Kew Palace © Historic Royal Palaces ● White Tower, Tower of London © Historic Royal Palaces ● Kensington Palace © Historic Royal Palaces ● Banqueting House © Historic Royal Palaces ● Hampton Court Palace © Historic Royal Palaces ● Grand Palace and Grand Cascade © Peterhof Museum ● Caserta – Royal Palace – Great staircase of honour © Soprintendenza BAPSAE. -

Cover Page the Handle Holds Various Files of This Leiden University Dissertation. Author: Krahe

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/28741 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Krahe, Cinta Title: Chinese porcelain and other orientalia and exotica in Spain during the Habsburg dynasty Issue date: 2014-09-18 Chinese Porcelain and other Orientalia and Exotica in Spain during the Habsburg Dynasty GENEALOGY OF THE SPANISH HABSBURG ROYAL HOUSE ROYAL HABSBURG OF THE SPANISH GENEALOGY 279 Cinta Krahe 280 Chinese Porcelain and other Orientalia and Exotica in Spain during the Habsburg Dynasty BIBLIOGRAPHY Abad Zardoya 2005 Carmen Abad Zardoya, La casa y los objetos. Espacio doméstico y cultura material en la Zaragoza de la primera mitad del Siglo XVIII, Zaragoza, 2005. Abad Zardoya 2009 Carmen Abad Zardoya, ‘ Por el bien y beneficios que de su mano hemos recibido: estudio documental de una donación de bienes muebles hecha por Tomás de Borja a su sobrino el duque de Lerma en 1608’ in Artigrama, no. 24, 2009, pp. 341-71. Addis 1970 John M. Addis, ‘Chinese Porcelain Found in the Philippines’, in Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society, vol. 37, 1970, pp. 17–36. Adhyatman and Ridho1984 Sumarah Adhyatman and Abu Ridho, Tempayan Martavans in Indonesia, Jakarta, 1984. (2nd ed.) Adhyatman 1987 Sumarah Adhyatman, Kendi, Jakarta, 1987. Adhyatman 1999 Sumarah Adhyatman, Zhangzhou (Swatow) Ceramics: Sixteenth to Seventeenth Centuries found in Indonesia, Jakarta, 1999. Aguado de los Reyes 1994 Jesús Aguado de los Reyes, Riqueza y Sociedad en la Sevilla del Siglo XVII, Seville, 1994. Aguado de los Reyes 1996 Jesús Aguado de los Reyes, Fortuna y miseria en la Sevilla del siglo XVII, Seville, 1996. -

A Renaissance Depiction of a Tornado

A RENAISSANCE DEPICTION OF A TORNADO BY KLAUS P. HOINKA AND MANUEL DE CASTRO A Flemish tapestry demonstrates how weather in sixteenth-century art can be of testimonial, decorative, or emblematic character. uring the Renaissance (1400–1600) meteorologi- discoveries of new lands and seas, which consider- cal phenomena attracted the interest of dil- ably enlarged and widened old ideas and concep- D etantes and artists. Interest in the weather ex- tions. Atmospheric phenomena never seen before pressed itself in the form of individual weather notes were identified by Western explorers, and climates (see Hellman 1901), the first serious attempts to pro- that were very different from those at home became vide some rules for predicting the weather (Hellmann known (Hellmann 1908). Among these new me- 1915, 1924a), and the well-established astrometeo- teorological phenomena, tornadoes and waterspouts rological approaches to forecasting the weather. The provoked considerable interest due to their damaging Renaissance period saw increasing attention toward effects, as well as their beauty. For centuries, the con- meteorological observations, in comparison to the cept of tornadoes was indistinguishable from people’s preceeding centuries where meteorology was domi- notions of other windstorms. The word “tornado” nated by Aristotle’s “Meteorologica” (3400 b.c.). The had an archaic meaning concerning variable, gusty invention of quantitative measuring devices, such as winds and rain, and, perhaps, thunderstorms near the thermometer (in 1607) and the barometer (1643), the equator. was yet to come. The Oxford English Dictionary (1989) defines a The fresh stimulus for weather observations came tornado in the following way: “In the 16th century at the end of the fifteenth century from the great navigators called a tornado (or ternado) a violent thunderstorm of the tropical Atlantic, with torren- tial rain, and often with sudden and violent gusts of AFFILIATIONS: HOINKA—Institut für Physik der Atmosphäre, wind . -

IBERIAN HOLIDAY MADRID, TOLEDO and SEGOVIA Monday, December 28, 2015 Through Sunday, January 3, 2016

AN IBERIAN HOLIDAY A NEW YEAR’S CELEBRATION IN MADRID, TOLEDO AND SEGOVIA* Monday, December 28, 2015 through Sunday, January 3, 2016 *Itinerary subject to change $ 3,600.00per person INCLUDING AIR $2,400.00 per person LAND ONLY $450.00 additional for SINGLE SUPPLEMENT Join us on our ANNUAL NEW YEAR’S TRIP takes you to SUNNY SPAIN AND THREE OF ITS MOST INTERESTING CITIES – MADRID, TOLEDO AND SEGOVIA. Our custom itinerary showcases a variety of museums, delicious dining experiences and fascinating sites from the ancient to the modern that come together on this wonderful Iberian Holiday. DAY 1 - MONDAY, DECEMBER 28 NEWARK Board United Airlines Flight #964 departing Newark Liberty Airport at 8:20pm for our NON-STOP trip to Madrid DAY 2 - TUESDAY, DECEMBER 29 MADRID (L/D) Arrive at Madrid’s Adolfo Suárez Madrid–Barajas Airport at 9:45am, gather our luggage and meet our coach and guide. After lunch, take a panoramic city tour where you will see many of Madrid’s beautiful Plazas, Monuments, Shopping Streets and Fountains. Visit some of the city’s different districts including the typical "castizo" (Castilian) quarter of "la Moreria." Check into the beautiful and centrally located Four Star Hotel NH Collection Madrid Paseo del Prado at 3:00 Relax for the rest of the afternoon. Dine with your fellow travelers at a festive Welcome Dinner DAY 3 - WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 30 MADRID (B/L/D) Meet our local guide for a short walk to the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum. Take a guided stroll down the history of European painting, from its beginning in the 13th century to the close of the 20th century by visiting works by Van Eyck, Dürer, Caravaggio, Rubens, Frans Hals, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Kirchner, Mondrian, Klee, Hopper, Rauschenberg .. -

WW2-Spain-Tripbook.Pdf

SPAIN 1 Page Spanish Civil War (clockwise from top-left) • Members of the XI International Brigade at the Battle of Belchite • Bf 109 with Nationalist markings • Bombing of an airfield in Spanish West Africa • Republican soldiers at the Siege of the Alcázar • Nationalist soldiers operating an anti-aircraft gun • HMS Royal Oakin an incursion around Gibraltar Date 17 July 1936 – 1 April 1939 (2 years, 8 months, 2 weeks and 1 day) Location Spain Result Nationalist victory • End of the Second Spanish Republic • Establishment of the Spanish State under the rule of Francisco Franco Belligerents 2 Page Republicans Nationalists • Ejército Popular • FET y de las JONS[b] • Popular Front • FE de las JONS[c] • CNT-FAI • Requetés[c] • UGT • CEDA[c] • Generalitat de Catalunya • Renovación Española[c] • Euzko Gudarostea[a] • Army of Africa • International Brigades • Italy • Supported by: • Germany • Soviet Union • Supported by: • Mexico • Portugal • France (1936) • Vatican City (Diplomatic) • Foreign volunteers • Foreign volunteers Commanders and leaders Republican leaders Nationalist leaders • Manuel Azaña • José Sanjurjo † • Julián Besteiro • Emilio Mola † • Francisco Largo Caballero • Francisco Franco • Juan Negrín • Gonzalo Queipo de Llano • Indalecio Prieto • Juan Yagüe • Vicente Rojo Lluch • Miguel Cabanellas † • José Miaja • Fidel Dávila Arrondo • Juan Modesto • Manuel Goded Llopis † • Juan Hernández Saravia • Manuel Hedilla • Carlos Romero Giménez • Manuel Fal Conde • Buenaventura Durruti † • Lluís Companys • José Antonio Aguirre Strength 1936 -

Catalogue of Rioja Wine Producers

#EENcanhelp VIII Inward Mission to La Rioja Wineries VIII Inward Mission to La Rioja Catalogue of Rioja Wine Producers 1 VIII Inward Mission to La Rioja Wineries WINERIES Participants for FOOD & WINE 2020. 2 VIII Inward Mission to La Rioja Wineries INDEX: ARRIEZU VINEYARDS ............................................................................................................................................. 5 BÁRBARA PALACIOS .............................................................................................................................................. 5 BERTA VALGAÑÓN GARCÍA .................................................................................................................................. 6 BODEGA/WINERY EDUARDO GARRIDO GARCIA .............................................................................................. 6 BODEGAS ALTANZA, S.A. ...................................................................................................................................... 7 BODEGAS ALVIA, CLASSIC AND PREMIUM RIOJA WINE ................................................................................. 7 BODEGAS ARADON ................................................................................................................................................ 8 BODEGAS BOHEDAL ............................................................................................................................................... 8 BODEGAS CASA LA RAD S.L. ................................................................................................................................ -

Internacional… . De Hispanistas… …

ASOCIACIÓN………. INTERNACIONAL… . DE HISPANISTAS… …. ASOCIACIÓN INTERNACIONAL DE HISPANISTAS 16/09 bibliografía publicado en colaboración con FUNDACIÓN DUQUES DE SORIA © Asociación Internacional de Hispanistas © Fundación Duques de Soria ISBN: 978-88-548-3311-1 Editora: Blanca L. de Mariscal Supervisión técnica: Claudia Lozano Maquetación: Debora Vaccari Índice EL HISPANISMO EN EL MUNDO: BIBLIOGRAFÍA Y CRÓNICA ÁFRICA Argelia, Marruecos y Túnez...................................................................................... 11 Egipto........................................................................................................................ 13 AMÉRICA Argentina.................................................................................................................... 14 Canadá........................................................................................................................ 22 Chile........................................................................................................................... 25 Estados Unidos........................................................................................................... 29 México........................................................................................................................ 41 Perú.............................................................................................................................49 Venezuela.................................................................................................................. -

Estudios Sobre Guerra Y Sociedad En La Monarquía Hispánica

ESTUDIOS SOBRE GUERRA Y SOCIEDAD EN LA MONARQUÍA HISPÁNICA Guerra marítima, estrategia, organización y cultura militar (1500-1700) Enrique García Hernán y Davide Maffi (Eds.) Historia de España y su proyección internacional XI Colección dirigida por Enrique García Hernán Estudios sobre guerra y sociedad en la Monarquía Hispánica : guerra marítima, estrategia, organización y cultura militar (1500-1700) / Enrique García Hernán y Davide Maffi (eds.) — Valencia : Albatros, D.L. V. 172-2017. — 943 p.: il. col.; 17 x 24 cm . — (Historia de España y su proyección internacional; 11) Incluye referencias bibliográficas e índice. ISBN: 978-84-7274-328-1. Depósito Legal: V. 172 - 2017. I. García Hernán, Enrique (1964-), ed. II. Maffi, Davide, ed. III. Serie. 1. Potencia marítima — España — 1500-1700. 2. España — Historia — 1500-1700. 3. América española. 94:355(460+7/8=134)”15/16”(082) La presente obra se ha realizado en el marco de los Proyectos de Investigación de I+D MINECO HAR2012-36884-C01-C02 (IP Enrique García Hernán y Óscar Recio Morales) y de los Proyectos HAR2015-64574-C2-1-P y C2-2-P (IP Óscar Recio Morales y José Cutillas Ferrer). Comité Científico Asesor de este volumen: Prof. Beatrice Heuser (Profesora de Política y Relaciones Internaciones, Universidad de Reading) Prof. Agustín González Enciso (Profesor de Historia Económica, Universidad de Navarra) Dr. Óscar Recio Morales (Profesor de Historia Moderna, Universidad Complutense de Madrid) Dr. Ismael Jiménez Jiménez (Departamento de Historia de América, Universidad de Sevilla) Dr. Antonio Jiménez Estrella (Profesor de Historia Moderna y de América, Universidad de Granada) Dra. Valentina Favarò (Profesora del Departamento de Cultura y Sociedad, Universidad de Palermo) Los capítulos de este libro han pasado por una evaluación peer review. -

Dirección General De Bibliotecas, Archivos Y Museos

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE BIBLIOTECAS, ARCHIVOS Y MUSEOS SUBDIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE BIBLIOTECAS, ARCHIVOS Y MUSEOS DEPARTAMENTO DE PATRIMONIO BIBLIOGRÁFICO Y DOCUMENTAL ARCHIVO DE VILLA THE ARCHIVO DE VILLA (TOWN ARCHIVE) OF MADRID The Archivo de Villa of Madrid contains, throughout its more than 18,500 running metres of shelves, documents created and received at the Madrid City Council since 1152. This archive was first mentioned in a Royal Provision of Charles V –Charles I of the Spanish empire– (1525), although the so-called 'ark of the three keys', a medieval deposit for the parchments of Madrid, is repeatedly mentioned in the books of resolutions since the 15th century. The Archive was finally set up in the 18th century. In 1748, the first professional archivist was appointed. The first regulations and operation instructions for the archive were approved in 1753 and it became a "Public Office" with the right to issue official certificates by virtue of a Royal Decree in 1781. This Institution was opened for research in 1844. It has changed its headquarters several times: Tower of the San Salvador church and Monastery of Santo Domingo (15th to 17th century), First Town Hall of Madrid (17th century-1868), Second Town Hall “Casa Panadería” in Plaza Mayor (1868-1987), Conde Duque barracks (1987-), but the custody of the materials it contains was never interrupted, not even during the Peninsular War (1808-1814), or during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). COLLECTIONS Except for two small acquisitions of private archives, the collections come from the Madrid City Council itself and from the City Councils that were annexed to Madrid during the fifties, in the past century. -

Violence, Protection and Commerce

This file is to be used only for a purpose specified by Palgrave Macmillan, such as checking proofs, preparing an index, reviewing, endorsing or planning coursework/other institutional needs. You may store and print the file and share it with others helping you with the specified purpose, but under no circumstances may the file be distributed or otherwise made accessible to any other third parties without the express prior permission of Palgrave Macmillan. Please contact [email protected] if you have any queries regarding use of the file. Proof 1 2 3 3 4 Violence, Protection and 5 6 Commerce 7 8 Corsairing and ars piratica in the Early Modern 9 Mediterranean 10 11 Wolfgang Kaiser and Guillaume Calafat 12 13 14 15 Like other maritime spaces, and indeed even large oceans such as the 16 Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean was not at all a ‘no man’s sea’ – as 17 the sea in general appears, opposed to territorial conquest and occupa- 18 tion of land, in a prominent way in Carl Schmitt’s opposition between 19 a terrestrian and a ‘free maritime’ spatial order.1 Large oceanic spaces 20 such as the Indian Ocean and smaller ones such as the Mediterranean 21 were both culturally highly saturated and legally regulated spaces.2 22 The Inner Sea has even been considered as a matrix of the legal and 23 political scenario of imposition of the Roman ‘policy of the sea’ that 24 had efficiently guaranteed free circulation and trade by eliminating 25 the pirates – Cicero’s ‘enemy of mankind’ 3– who formerly had infected the 26 Mediterranean.