PDF (Volume 2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arts Council Ballet Policy Review

ARTS COUNCIL BALLET POLICY REVIEW November 2013 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CHAPTER 1: HISTORICAL CONTEXT 1.1 Chapter introduction 1.2 A brief overview of ballet history 1.3 Ballet’s relevance in western contemporary society 1.4 Irish ballet in brief 1.5 Chapter conclusion CHAPTER 2: EDUCATION 2.1 Chapter introduction 2.2 Impediments to the development of formal dance education in Ireland 2.3 A brief overview of the current provision for pre-vocational dance training in Ireland 2.4 A possible model for professional dance education in Ireland 2.5 Proposed outline of course content for a BA in Dance 2.6 The positioning of a professional dance programme within a university setting and the development of international associations for quality assurance 2.7 Chapter conclusion CHAPTER 3: AN AUDIENCE PERSPECTIVE 3.1 Chapter introduction 3.2 Audience data sources 3.3 Audience data observations 3.4 Participation observations 3.5 Strategies for nurturing and developing audiences/engagement. 3.5.1 Research 3.5.2 Skills 3.5.3 Partnerships 3.5.4 Branding 3.5.5 Programming 3.5.6 External perceptions 3.5.7 Participatory activities 3.6 Chapter conclusion CHAPTER 4: PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE 4.1 Chapter introduction 4.2 Common factors 4.3 Artistic considerations and planning 2 4.3.1 A commitment to creativity and moving the art form forward. 4.3.2 Producing a ‘balanced’ programme 4.3.3 Imaginative programming achieved taking account of practical considerations 4.4 Model of practice for Ireland 4.5 Chapter conclusion APPENDIX 1: ARTS COUNCIL CONSULTATION PROCESS NOTES APPENDIX 2: ABOUT THE AUTHORS 3 INTRODUCTION In May 2006 the Arts Council commissioned an independent review of the context and issues affecting professional ballet in Ireland. -

NABMSA Reviews a Publication of the North American British Music Studies Association

NABMSA Reviews A Publication of the North American British Music Studies Association Vol. 5, No. 2 (Fall 2018) Ryan Ross, Editor In this issue: Ita Beausang and Séamas de Barra, Ina Boyle (1889–1967): A Composer’s Life • Michael Allis, ed., Granville Bantock’s Letters to William Wallace and Ernest Newman, 1893–1921: ‘Our New Dawn of Modern Music’ • Stephen Connock, Toward the Rising Sun: Ralph Vaughan Williams Remembered • James Cook, Alexander Kolassa, and Adam Whittaker, eds., Recomposing the Past: Representations of Early Music on Stage and Screen • Martin V. Clarke, British Methodist Hymnody: Theology, Heritage, and Experience • David Charlton, ed., The Music of Simon Holt • Sam Kinchin-Smith, Benjamin Britten and Montagu Slater’s “Peter Grimes” • Luca Lévi Sala and Rohan Stewart-MacDonald, eds., Muzio Clementi and British Musical Culture • Christopher Redwood, William Hurlstone: Croydon’s Forgotten Genius Ita Beausang and Séamas de Barra. Ina Boyle (1889-1967): A Composer’s Life. Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press, 2018. 192 pp. ISBN 9781782052647 (hardback). Ina Boyle inhabits a unique space in twentieth-century music in Ireland as the first resident Irishwoman to write a symphony. If her name conjures any recollection at all to scholars of British music, it is most likely in connection to Vaughan Williams, whom she studied with privately, or in relation to some of her friends and close acquaintances such as Elizabeth Maconchy, Grace Williams, and Anne Macnaghten. While the appearance of a biography may seem somewhat surprising at first glance, for those more aware of the growing interest in Boyle’s music in recent years, it was only a matter of time for her life and music to receive a more detailed and thorough examination. -

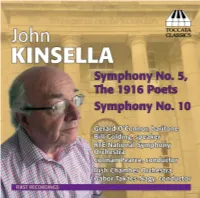

Toccata Classics TOCC0242 Notes

Americas, and from further aield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, JOHN KINSELLA, IRISH SYMPHONIST by Séamas da Barra John Kinsella was born in Dublin on 8 April 1932. His early studies at the Dublin College of Music were devoted to the viola as well as to harmony and counterpoint, but he is essentially self-taught as a composer. He started writing music as a teenager and although he initially adopted a straightforward, even conventional, tonal idiom, he began to take a serious interest in the compositional techniques of the European avant-garde from the early 1960s. He embraced serialism in particular as a liberating influence on his creative imagination, and he produced a substantial body of work during this period that quickly established him in Ireland as one of the most interesting younger figures of the day. In 1968 Kinsella was appointed Senior Assistant in the music department of Raidió Teilefís Éireann (RTÉ), the Irish national broadcasting authority, a position that allowed him to become widely acquainted with the latest developments in contemporary music, particularly through the International Rostrum of Composers organised under the auspices of UNESCO. But much of what he heard at these events began to strike him as dispiritingly similar in content, and he was increasingly persuaded that for many of his contemporaries conformity with current trends had become more P important than a desire to create out of inner conviction. As he found himself growing disillusioned with the avant-garde, his attitude to his own work began to change and he came to question the artistic validity of much of what he had written. -

Passion and Intellect in the Music of Elizabeth Maconchy DBE (1907–1994)

Passion and Intellect in the Music of Elizabeth Maconchy DBE (1907–1994) Ailie Blunnie Thesis submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Master of Literature in Music Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare July 2010 Head of Department: Professor Fiona Palmer Supervisor: Dr Martin O’Leary Contents Acknowledgements i List of Abbreviations iii List of Illustrations iv Preface ix Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Part 1: The Early Years (1907–1939): Life and Historical Context 8 Early Education 10 Royal College of Music 11 Octavia Scholarship and Promenade Concert 17 New Beginnings: Leaving College 19 Macnaghten–Lemare Concerts 22 Contracting Tuberculosis 26 Part 2: Music of the Early Years 31 National Trends 34 Maconchy’s Approach to Composition 36 Overview of Works of this Period 40 The Land: Introduction 44 The Land: Movement I: ‘Winter’ 48 The Land: Movement II: ‘Spring’ 52 The Land: Movement III: ‘Summer’ 55 The Land: Movement IV: ‘Autumn’ 57 The Land: Summary 59 The String Quartet in Context 61 Maconchy’s String Quartets of the Period 63 String Quartet No. 1: Introduction 69 String Quartet No. 1: Compositional Procedures 74 String Quartet No. 1: Summary 80 String Quartet No. 2: Introduction 81 String Quartet No. 2: Movement I 83 String Quartet No. 2: Movement II 88 String Quartet No. 2: Movement III 91 String Quartet No. 2: Movement IV 94 Part 2: Summary 97 Chapter 3 Part 1: The Middle Years (1940–1969): Life and Historical Context 100 World War II 101 After the War 104 Accomplishments of this Period 107 Creative Dissatisfaction 113 Part 2: Music of the Middle Years 115 National Trends 117 Overview of Works of this Period 117 The String Quartet in Context 121 Maconchy’s String Quartets of this Period 122 String Quartet No. -

Cork City and County Archives Index to Listed Collections with Scope and Content

Cork City and County Archives Index to Listed Collections with Scope and Content A State of the Ref. IE CCCA/U73 Date: 1769 Level: item Extent: 32pp Diocese of Cloyne Scope and Content: Photocopy of MS. volume 'A State of The Diocese of Cloyne With Respect to the Several Parishes... Containing The State of the Churches, the Glebes, Patrons, Proxies, Taxations in the King's Books, Crown – Rents, and the Names of the Incumbents, with Other Observations, In Alphabetical Order, Carefully collected from the Visitation Books and other Records preserved in the Registry of that See'. Gives ecclesiastical details of the parishes of Cloyne; lists the state of each parish and outlines the duties of the Dean. (Copy of PRONI T2862/5) Account Book of Ref. IE CCCA/SM667 Date: c.1865 - 1875 Level: fonds Extent: 150pp Richard Lee Scope and Content: Account ledger of Richard Lee, Architect and Builder, 7 North Street, Skibbereen. Included are clients’ names, and entries for materials, labourers’ wages, and fees. Pages 78 to 117 have been torn out. Clients include the Munster Bank, Provincial Bank, F McCarthy Brewery, Skibbereen Town Commissioners, Skibbereen Board of Guardians, Schull Board of Guardians, George Vickery, Banduff Quarry, Rev MFS Townsend of Castletownsend, Mrs Townsend of Caheragh, Richard Beamish, Captain A Morgan, Abbeystrewry Church, Beecher Arms Hotel, and others. One client account is called ‘Masonic Hall’ (pp30-31) [Lee was a member of Masonic Lodge no.15 and was responsible for the building of the lodge room]. On page 31 is written a note regarding the New Testament. Account Book of Ref. -

Connections in Motion: Dance in Irish and German Literature, Film and Culture

16th International Conference in Irish-German Studies Connections in Motion: Dance in Irish and German Literature, Film and Culture Irish Centre of Transnational Studies (Mary Immaculate College) and Centre of Irish-German Studies (University of Limerick) in collaboration with the Irish World Academy for Music and Dance, the National Dance Archive of Ireland, the School of Culture and Communication and the School of Design (University of Limerick) 31 October-1 November 2016 Joint organisers Dr. Sabine Egger (Irish Centre for Transnational Studies, MIC); Dr. Catherine Foley (Irish World Academy for Music and Dance, UL/National Dance Archive of Ireland); Prof. Margaret Harper (Glucksman Chair in Contemporary Writing in English, School of Culture and Communication, UL); Dr. Gisela Holfter (Centre Venue for Irish-German Studies, UL); Dr. Deirdre Mulrooney (Dublin); Irish World Academy of Music and Dance Jan Frohburg (School of Design, UL). University of Limerick http://www.irishworldacademy.ie/venue/map-directions/ NOTE: Room numbers will be provided at the registration desk. Supported by Contact Goethe-Institut Irland; DAAD/German Academic Exchange Service; [email protected] German Embassy, Dublin; Irish World Academy for Music and Dance (UL); National Dance Archive of Ireland; School of Modern Languages & Applied Linguistics (UL); School of Culture and Further Information Communication (UL); Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social http://www.ictstudies.eu/news-events/ Sciences (UL); School of Design (UL); Institute of Irish Studies http://ulsites.ul.ie/irishgerman/ (MIC); Department of German Studies (MIC). http://www.irishworldacademy.ie/ NOTE: Registration fee waivers apply to participants availing of early bird registration, centre members and students. -

Mike Mcgrath-Bryan M.A

MIKE MCGRATH-BRYAN M.A. Journalism with New Media, CIT Selected Features Journalism & Content Work 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS: GENDER REBELS: FIGHTING FOR RIGHTS AND VISIBILITY (Evening Echo, August 31st 2018) 3 MOVEMBER: “IT’S AN AWFUL SHOCK TO THE SYSTEM” (Evening Echo, November 13th 2017) 7 REBEL READS: TURNING THE PAGE (Totally Cork, September 2018) 10 FRANCISCAN WELL: FEM-ALE PRESSURE (Evening Echo, July 26th 2018) 12 CORK VINTAGE MAP: OF A CERTAIN VINTAGE (Totally Cork, December 6th 2016) 14 THE RUBBERBANDITS: HORSE SENSE (Evening Echo, December 12, 2016) 16 LANKUM: ON THE CUSP OF THE UNKNOWN (Village Magazine, November 2017) 19 CAOIMHÍN O’RAGHALLAIGH: “IT’S ABOUT FINDING THE RIGHT SPACE” (RTÉ Culture, September 6th 2018) 25 THE JAZZ AT 40: PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE (Evening Echo: Jazz Festival Special, October 17th 2017) 28 CORK MIDSUMMER FESTIVAL: THE COLLABORATIVE MODEL (Totally Cork, May 2018) 31 DRUID THEATRE: “VERY AWARE OF ITSELF” (Evening Echo, February 12th 2018) 33 CORK CITY BALLET: EN POINTE (Evening Echo, September 3rd, 2018) 35 2 GENDER REBELS: FIGHTING FOR RIGHTS AND VISIBILITY (Evening Echo, August 31st 2018) Gender Rebels are a group dedicated to working on the rights of transgender, intersex and non-binary people in Cork City, negotiating obstacles both infrastructural and everyday, and providing an outlet for social events and peer support. Mike McGrath-Bryan speaks with chairperson Jack Fitzgerald. With Pride month in the rear view mirror for another year, and celebrations around the country winding down, it’s easy to bask in the colour, pomp and circumstance that the weekend’s proceedings confer on the city. -

DI-News-October-2007.Pdf

OCTOBER 2007 dance ireland NEWS Dance Ireland, the trading name of the Association of Professional Dancers in Ireland Ltd., was established in 1989 as a membership-led organisation dedicated to the promotion of professional dance practice in Ireland. Since that time it has evolved into a national, strategic resource organisation whose core aims include the promotion of dance as a vibrant artform, the provision of support and practical resources for professional dance artists and advocacy on dance and choreography issues. Dance Ireland also manages DanceHouse, a purpose-built, state-of-the-art dance rehearsal venue, located in the heart of Dublin’s north-east inner city. DanceHouse is at the heart of Dance Ireland activities, as well as being a home for professional dance artists and the wider dance community. In addition to hosting our comprehensive artistic programme of professional classes, seminars and workshops, and a fully-equipped artists’ resource room, DanceHouse offers a range of evening classes to cater to the interests and needs of the general public. BOARD MEMBERS Liz Roche Chairperson, Ríonach Ní Néill Secretary, Muirne Bloomer, Adrienne Brown, Megan Kennedy, Joseph Melvin, Fearghus Ó Conchúir, John Scott, Gaby Smith. DANCE IRELAND PERSONNEL Paul Johnson, Chief Executive Siân Cunningham, General Manager/DanceHouse Elisabetta Bisaro, Development Officer Duncan Keegan, Administrator Brenda Crea & Glenn Montgomery, Receptionists/Administrative Assistants Dance Ireland, DanceHouse, Liberty Corner, Foley Street, Dublin 1. Tel: 01 855 8800 Fax: 01 819 7529 Email: [email protected] Website: www.danceireland.ie Dance Ireland News is published 12 times a year Published by Dance Ireland, DanceHouse, Liberty Corner, Foley St, Dublin 1, Ireland. -

Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Masters Applied Arts 2018 Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930. David Scott Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appamas Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Scott, D. (2018) Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900-1930.. Masters thesis, DIT, 2018. This Theses, Masters is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Examining the Irish Art Song: Original Song Settings of Irish Texts by Irish Composers, 1900–1930 David Scott, B.Mus. Thesis submitted for the award of M.Phil. to the Dublin Institute of Technology College of Arts and Tourism Supervisor: Dr Mark Fitzgerald Dublin Institute of Technology Conservatory of Music and Drama February 2018 i ABSTRACT Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, arrangements of Irish airs were popularly performed in Victorian drawing rooms and concert venues in both London and Dublin, the most notable publications being Thomas Moore’s collections of Irish Melodies with harmonisations by John Stephenson. Performances of Irish ballads remained popular with English audiences but the publication of Stanford’s song collection An Irish Idyll in Six Miniatures in 1901 by Boosey and Hawkes in London marks a shift to a different type of Irish song. -

Copyright 2010, Michigan Opera Theatre Copyright 2010, Michigan Opera Theatre the Official Magazine 1Sla of the Detroit Opera House ~~~Em~

Copyright 2010, Michigan Opera Theatre Copyright 2010, Michigan Opera Theatre The Official Magazine 1Sla of the Detroit Opera House ~~~eM~_---. Michigan Opera TheatreS 2000-2001 Season is lovingly dedicated to the memory of Lynn A. Townsend and Robert E. Dewar BRAVO IS A MICHIGAN OPERA THEATRE PUBLICATION Dr. David DiChiera, General Director Laura Wyss, Editor CONTRIBUTORS MICHIGAN OPERA THEATRE STAFF Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Staff American Ballet Theatre Staff Arts'League of Michigan Staff Ballet Internationale Staff University Musical Society Staff PUBLISHER Live Publishing Company Frank Cucciarre, Design and Art Direction Chuck Rosenberg, Copy Editor Toby Faber, Director of Advertising Sales COVER PHOTO Detail from the Detroit Opera House, Mark]. Mancinelli, MJM Photography A special thanks to Jeanette Pawlaczyk and Bill Carroll Michigan Opera Theatre would like to thank Harmony House Records for donating season recordings and videos. Michigan Opera Theatre's 2000-2001 subscription and Single tickets have been graciously sponsored by Hunter House, Harmonie Park. METAL RESTORATION Physicians' service provided by Henry Ford Medical Center. Dent and scratcl-l. removal Re-a ttachmen t Alitalia is the official airline ~f Michigan Opera Theatre. • Sterling, brass, copper, bronze, and plate Pepsi-Cola is the official soft drink and juice provider for the Detroit Opera House. Starbucks Coffee is the official coffee of the Detroit Opera House. Ben Wearley, silversmith Steinway is the official piano of the Detroit Opera House and Michigan Opera Theatre. Steinway pianos are (248) 549-3016 provided by Hammel MuSiC, exclusive representative for Steinway and Sons in Michigan. President Tuxedo is the official provider of fonnal wear for the Detroit Opera House. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 84,1964-1965

£uJ&$4 -/ X) %r r BOSTON Iff SYMPHONY ORCHES FOUNDED IN 1881 BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON 24 i \A\ ^fe*' ^s H EIGHTY-FOURTH SEASON 1964-1965 TAKE NOTE The precursor of the oboe goes back to antiquity — it was found in Sumeria (2800 bc) and was the Jewish halil, the Greek aulos, and the Roman tibia • After the renaissance, instruments of this type were found in complete families ranging from the soprano to the bass. The higher or smaller instruments were named by the French "haulx-bois" or "hault- bois" which was transcribed by the Italians into oboe which name is now used in English, German and Italian to distinguish the smallest instrument • In a symphony orchestra, it usually gives the pitch to the other instruments • Is it time for you to take note of your insurance needs? • We welcome the opportunity to analyze your present program and offer our professional service to provide you with intelligent, complete protection. We respectfully invite your inquiry i . , ... CHARLES H. WATKINS CO. & /obRION, RUSSELL 8c CO. Richard P. Nyquist — Charles G. Carleton / 147 milk street boston 9, Massachusetts/ Insurance of Every Description 542-1250 EIGHTY-FOURTH SEASON, 1964-1965 CONCERT BULLETIN OF THE Boston Symphony Orchestra ERICH LEINSDORF, Music Director Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk Copyright, 1965, by Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot • President Talcott M. Banks • Vice-President Richard C. Paine Treasurer Abram Berkowitz Henry A. Laughlin The Rev. Theodore P. Ferris Rt. -

Copyright 2014 Renée Chérie Clark

Copyright 2014 Renée Chérie Clark ASPECTS OF NATIONAL IDENTITY IN THE ART SONGS OF RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS BEFORE THE GREAT WAR BY RENÉE CHÉRIE CLARK DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Christina Bashford, Chair Associate Professor Gayle Sherwood Magee Professor Emeritus Herbert Kellman Professor Emeritus Chester L. Alwes ABSTRACT This dissertation explores how the art songs of English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) composed before the Great War expressed the composer’s vision of “Englishness” or “English national identity”. These terms can be defined as the popular national consciousness of the English people. It is something that demands continual reassessment because it is constantly changing. Thus, this study takes into account two key areas of investigation. The first comprises the poets and texts set by the composer during the time in question. The second consists of an exploration of the cultural history of British and specifically English ideas surrounding pastoralism, ruralism, the trope of wandering in the countryside, and the rural landscape as an escape from the city. This dissertation unfolds as follows. The Introduction surveys the literature on Vaughan Williams and his songs in particular on the one hand, and on the other it surveys a necessarily selective portion of the vast literature of English national identity. The introduction also explains the methodology applied in the following chapters in analyzing the music as readings of texts. The remaining chapters progress in the chronological order of Vaughan Williams’s career as a composer.