Copyright 2014 Renée Chérie Clark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS ROYAL LIVERPOOL PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA ANDREW MANZE Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872 –1958)

A LONDON SYMPHONY SYMPHONY NO. 8 VAUGHAN WILLIAMS ROYAL LIVERPOOL PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA ANDREW MANZE Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872 –1958) Symphony No.2 in G ‘A London Symphony’ 1. I. Lento – Allegro risoluto (molto pesante) 14.29 2. II. Lento 10.59 3. III. Scherzo (Nocturne): Allegro vivace 7.55 4. IV. Andante con moto – Maestoso alla Marcia (quasi lento) – Allegro – 13.19 Maestoso alla Marcia (alla I) – Epilogue (Andante sostenuto) Symphony No.8 in D minor 5. I. Fantasia (Variazioni senza tema) 10.47 6. II. Scherzo alla marcia (per strumenti a fiato): Allegro alla marcia 3.50 7. III. Cavatina (per strumenti ad arco): Lento espressivo 9.03 8. IV. Toccata: Moderato maestoso 5.06 Total timing: 75.33 ROYAL LIVERPOOL PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA ANDREW MANZE CONDUCTOR 2 SYMPHONIES EARLY AND LATE a kind of spiritual and musical summation; we have come full circle, evoking the silent river’s inexorable flow and the veiling mists as metaphors for some profound spiritual truth. At Symphony No.2 ‘A London Symphony’ the very end a muted violin plays a last soaring reminiscence of the theme over soft strings. The two or three years immediately before the outbreak of the Great War were a high point Muted cornets, trumpets and horns sound a soft chord and then, like the sun breaking for British music, when the music of a new generation of younger composers was beginning through, the brass all remove their mutes for the final chord. to appear on concert programmes. Slightly older than the rest, Vaughan Williams was already known for On Wenlock Edge , A Sea Symphony and the Tallis Fantasia , and in March 1914 his Towards the end of his life Vaughan Williams cited H.G. -

Guitar Syllabus

TheThe LLeinsteinsteerr SScchoolhool ooff MusMusiicc && DDrramama Established 1904 Singing Grade Examinations Syllabus The Leinster School of Music & Drama Singing Grade Examinations Syllabus Contents The Leinster School of Music & Drama ____________________________ 2 General Information & Examination Regulations ____________________ 4 Grade 1 ____________________________________________________ 6 Grade 2 ____________________________________________________ 9 Grade 3 ____________________________________________________ 12 Grade 4 ____________________________________________________ 15 Grade 5 ____________________________________________________ 19 Grade 6 ____________________________________________________ 23 Grade 7 ____________________________________________________ 27 Grade 8 ____________________________________________________ 33 Junior & Senior Repertoire Recital Programmes ________________________ 35 Performance Certificate __________________________________________ 36 1 The Leinster School of Music & Drama Singing Grade Examinations Syllabus TheThe LeinsterLeinster SchoolSchool ofof MusicMusic && DraDrammaa Established 1904 "She beckoned to him with her finger like one preparing a certificate in pianoforte... at the Leinster School of Music." Samuel Beckett Established in 1904 The Leinster School of Music & Drama is now celebrating its centenary year. Its long-standing tradition both as a centre for learning and examining is stronger than ever. TUITION Expert individual tuition is offered in a variety of subjects: • Singing and -

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS His Broadcasting Career Covers Both Radio and Television

557643bk VW US 16/8/05 5:02 pm Page 5 8.557643 Iain Burnside Songs of Travel (Words by Robert Louis Stevenson) 24:03 1 The Vagabond 3:24 The English Song Series • 14 DDD Iain Burnside enjoys a unique reputation as pianist and broadcaster, forged through his commitment to the song 2 Let Beauty awake 1:57 repertoire and his collaborations with leading international singers, including Dame Margaret Price, Susan Chilcott, 3 The Roadside Fire 2:17 Galina Gorchakova, Adrianne Pieczonka, Amanda Roocroft, Yvonne Kenny and Susan Bickley; David Daniels, 4 John Mark Ainsley, Mark Padmore and Bryn Terfel. He has also worked with some outstanding younger singers, Youth and Love 3:34 including Lisa Milne, Sally Matthews, Sarah Connolly; William Dazeley, Roderick Williams and Jonathan Lemalu. 5 In Dreams 2:18 VAUGHAN WILLIAMS His broadcasting career covers both radio and television. He continues to present BBC Radio 3’s Voices programme, 6 The Infinite Shining Heavens 2:15 and has recently been honoured with a Sony Radio Award. His innovative programming led to highly acclaimed 7 Whither must I wander? 4:14 recordings comprising songs by Schoenberg with Sarah Connolly and Roderick Williams, Debussy with Lisa Milne 8 Songs of Travel and Susan Bickley, and Copland with Susan Chilcott. His television involvement includes the Cardiff Singer of the Bright is the ring of words 2:10 World, Leeds International Piano Competition and BBC Young Musician of the Year. He has devised concert series 9 I have trod the upward and the downward slope 1:54 The House of Life • Four poems by Fredegond Shove for a number of organizations, among them the acclaimed Century Songs for the Bath Festival and The Crucible, Sheffield, the International Song Recital Series at London’s South Bank Centre, and the Finzi Friends’ triennial The House of Life (Words by Dante Gabriel Rossetti) 26:27 festival of English Song in Ludlow. -

Saken Bergaliyev Matr.Nr. 61800203 Benjamin Britten Lachrymae

Saken Bergaliyev Matr.Nr. 61800203 Benjamin Britten Lachrymae: Reflections on a Song of Dowland for viola and piano- reflections or variations? Master thesis For obtaining the academic degree Master of Arts of course Solo Performance Viola in Anton Bruckner Privatuniversität Linz Supervised by: Univ.Doz, Dr. M.A. Hans Georg Nicklaus and Mag. Predrag Katanic Linz, April 2019 CONTENT Foreword………………………………………………………………………………..2 CHAPTER 1………………………………...………………………………….……....6 1.1 Benjamin Britten - life, creativity, and the role of the viola in his life……..…..…..6 1.2 Alderburgh Festival……………………………......................................................14 CHAPTER 2…………………………………………………………………………...19 John Dowland and his Lachrymae……………………………….…………………….19 CHAPTER 3. The Lachrymae of Benjamin Britten.……..……………………………25 3.1 Lachrymae and Nocturnal……………………………………………………….....25 3.2 Structure of Lachrymae…………………………………………………………....28 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………..39 Bibliography……………………………………….......................................................43 Affidavit………………………………………………………………………………..45 Appendix ……………………………………………………………………………....46 1 FOREWORD The oeuvre of the great English composer Benjamin Britten belongs to one of the most sig- nificant pages of the history of 20th-century music. In Europe, performers and the general public alike continue to exhibit a steady interest in the composer decades after his death. Even now, the heritage of the master has great repertoire potential given that the number of his written works is on par with composers such as S. Prokofiev, F. Poulenc, D. Shostako- vich, etc. The significance of this figure for researchers including D. Mitchell, C. Palmer, F. Rupprecht, A. Whittall, F. Reed, L. Walker, N. Abels and others, who continue to turn to various areas of his work, is not exhausted. Britten nature as a composer was determined by two main constants: poetry and music. In- deed, his art is inextricably linked with the word. -

SIBL. . V^'- ' / Proquest Number: 10096794

-TÂ/igSEOBSIAW p o e t s : A. CBIIXCÆJEaaMIBA!ElûIif--CÆJ^ POETRY '' ARD POETIC THEORY. “ KATHARIKE COOKE. M. P h i l . , SIBL. v^'- ' / ProQuest Number: 10096794 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10096794 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 SYNOPSIS. As the Introduction explains this thesis sets out to look at the Georgians* achievement in poetry in the light of their intentions as avowed in prose and their methods as exemplified hy their poems. This is chiefly a critical exercise hut history has heen used to clear away the inevitable distortion which results from looking at Georgian poetry after fifty years of Eliot- influenced hostility. The history of the movement is dealt with in Chapter 2. The next three chapters examine aspects of poetry which the Georgians themselves con sidered most interesting. Chapter 3 deals with form, Chapter 4 with diction and Chapter 5 with inspiration or attitude to subject matter. Chapter 6 looks at the aspect of Georgianism most commonly thought by later readers to define the movement, th a t is i t s subjects. -

Wild Worship of a Lost and Buried Past”: Enchanted Bofulletin the History of Archaeology Archaeologies and the Cult of Kata, 1908–1924

Wickstead, H 2017 “Wild Worship of a Lost and Buried Past”: Enchanted Bofulletin the History of Archaeology Archaeologies and the Cult of Kata, 1908–1924. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, 27(1): 4, pp. 1–18, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/bha-596 RESEARCH PAPER “Wild Worship of a Lost and Buried Past”: Enchanted Archaeologies and the Cult of Kata, 1908–1924 Helen Wickstead Histories of archaeology traditionally traced the progress of the modern discipline as the triumph of secular disenchanted science over pre-modern, enchanted, world-views. In this article I complicate and qualify the themes of disenchantment and enchantment in archaeological histories, presenting an analysis of how both contributed to the development of scientific theory and method in the earliest decades of the twentieth century. I examine the interlinked biographies of a group who created a joke religion called “The Cult of Kata”. The self-described “Kataric Circle” included notable archaeologists Harold Peake, O.G.S. Crawford and Richard Lowe Thompson, alongside classicists, musicians, writers and performing artists. The cult highlights the connections between archaeology, theories of performance and the performing arts – in particular theatre, music, folk dance and song. “Wild worship” was linked to the consolidation of collectivities facilitating a wide variety of scientific and artistic projects whose objectives were all connected to dreams of a future utopia. The cult parodied archaeological ideas and methodologies, but also supported and expanded the development of field survey, mapping and the interpretation of archaeological distribution maps. The history of the Cult of Kata shows how taking account of the unorthodox and the interdisciplinary, the humorous and the recreational, is important within generously framed approaches to histories of the archaeological imagination. -

Six Folk Songs from Norfolk

1 Six folk songs from norfolk Voice & Piano by E.J. Moeran VOCAL SCORE 2 This score is in the Public Domain and has No Copyright under United States law. Anyone is welcome to make use of it for any purpose. Decorative images on this score are also in the Public Domain and have No Copyright under United States law. No determination was made as to the copyright status of these materials under the copyright laws of other countries. They may not be in the Public Domain under the laws of other countries. EHMS makes no warranties about the materials and cannot guarantee the accuracy of this Rights Statement. You may need to obtain other permissions for your intended use. For example, other rights such as publicity, privacy or moral rights may limit how you may use the material. You are responsible for your own use. http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/NoC-US/1.0/ Text written for this score, including project information and descriptions of individual works does have a new copyright, but is shared for public reuse under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0 International) license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Cover Image: ”Peace (detail)” by Benjamin Williams Leader, 1915 3 The “renaissance” in English music is generally agreed to have started in the late Victorian period, beginning roughly in 1880. Public demand for major works in support of the annual choral festivals held throughout England at that time was considerable which led to the creation of many large scale works for orchestra with soloists and chorus. -

Constructing the Archive: an Annotated Catalogue of the Deon Van Der Walt

(De)constructing the archive: An annotated catalogue of the Deon van der Walt Collection in the NMMU Library Frederick Jacobus Buys January 2014 Submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Master of Music (Performing Arts) at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University Supervisor: Prof Zelda Potgieter TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DECLARATION i ABSTRACT ii OPSOMMING iii KEY WORDS iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION TO THIS STUDY 1 1. Aim of the research 1 2. Context & Rationale 2 3. Outlay of Chapters 4 CHAPTER 2 - (DE)CONSTRUCTING THE ARCHIVE: A BRIEF LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CHAPTER 3 - DEON VAN DER WALT: A LIFE CUT SHORT 9 CHAPTER 4 - THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION: AN ANNOTATED CATALOGUE 12 CHAPTER 5 - CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 18 1. The current state of the Deon van der Walt Collection 18 2. Suggestions and recommendations for the future of the Deon van der Walt Collection 21 SOURCES 24 APPENDIX A PERFORMANCE AND RECORDING LIST 29 APPEDIX B ANNOTED CATALOGUE OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION 41 APPENDIX C NELSON MANDELA METROPOLITAN UNIVERSTITY LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SERVICES (NMMU LIS) - CIRCULATION OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT (DVW) COLLECTION (DONATION) 280 APPENDIX D PAPER DELIVERED BY ZELDA POTGIETER AT THE OFFICIAL OPENING OF THE DEON VAN DER WALT COLLECTION, SOUTH CAMPUS LIBRARY, NMMU, ON 20 SEPTEMBER 2007 282 i DECLARATION I, Frederick Jacobus Buys (student no. 211267325), hereby declare that this treatise, in partial fulfilment for the degree M.Mus (Performing Arts), is my own work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment or completion of any postgraduate qualification to another University or for another qualification. -

RCA LHMV 1 His Master's Voice 10 Inch Series

RCA Discography Part 33 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA LHMV 1 His Master’s Voice 10 Inch Series Another early 1950’s series using the label called “His Master’s Voice” which was the famous Victor trademark of the dog “Nipper” listening to his master’s voice. The label was retired in the mid 50’s. LHMV 1 – Stravinsky The Rite of Spring – Igor Markevitch and the Philharmonia Orchestra [1954] LHMV 2 – Vivaldi Concerto for Oboe and String Orchestra F. VII in F Major/Corelli Concerto grosso Op. 6 No. 4 D Major/Clementi Symphony Op. 18 No. 2 – Renato Zanfini, Renato Fasano and Virtuosi di Roma [195?] LHMV 3 – Violin Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 2 (Bartok) – Yehudi Menuhin, Wilhelm Furtwangler and the Philharmonia Orchestra [1954] LHMV 4 – Beethoven Concerto No. 5 in E Flat Op. 73 Emperor – Edwin Fischer, Wilhelm Furtwangler and the Philharmonia Orchestra [1954] LHMV 5 – Brahms Concerto in D Op. 77 – Gioconda de Vito, Rudolf Schwarz and the Philharmonia Orchestra [1954] LHMV 6 - Schone Mullerin Op. 25 The Maid of the Mill (Schubert) – Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Gerald Moore [1/55] LHMV 7 – Elgar Enigma Variations Op. 36 Wand of Youth Suite No. 1 Op. 1a – Sir Adrian Boult and the London Philharmonic Orchestra [1955] LHMV 8 – Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F/Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D – Harold Jackson, Gareth Morris, Herbert Sutcliffe, Manoug Panikan, Raymond Clark, Gerraint Jones, Edwin Fischer and the Philharmonia Orchestra [1955] LHMV 9 – Beethoven Symphony No. 5 in C Minor Op. -

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten Through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Jensen, Joni Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 21:33:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/193556 A COMPARISON OF ORIGINS AND INFLUENCES IN THE MUSIC OF VAUGHAN WILLIAMS AND BRITTEN THROUGH ANALYSIS OF THEIR FESTIVAL TE DEUMS by Joni Lynn Jensen Copyright © Joni Lynn Jensen 2005 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC AND DANCE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 5 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Joni Lynn Jensen entitled A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughan Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Bruce Chamberlain _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Elizabeth Schauer _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Josef Knott Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

Vaughan Williams

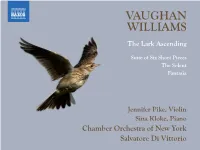

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS The Lark Ascending Suite of Six Short Pieces The Solent Fantasia Jennifer Pike, Violin Sina Kloke, Piano Chamber Orchestra of New York Salvatore Di Vittorio Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958): The Lark Ascending a flinty, tenebrous theme for the soloist is succeeded by an He rises and begins to round, The Solent · Fantasia for Piano and Orchestra · Suite of Six Short Pieces orchestral statement of a chorale-like melody. The rest of He drops the silver chain of sound, the work offers variants upon these initial ideas, which are Of many links without a break, rigorously developed. Various contrasting sections, In chirrup, whistle, slur and shake. Vaughan Williams’ earliest compositions, which date from The opening phrase of The Solent held a deep significance including a scherzo-like passage, are heralded by rhetorical 1895, when he left the Royal College of Music, to 1908, for the composer, who returned to it several times throughout statements from the soloist before the coda recalls the For singing till his heaven fills, the year he went to Paris to study with Ravel, reveal a his long creative life. Near the start of A Sea Symphony chorale-like theme in a virtuosic manner. ’Tis love of earth that he instils, young creative artist attempting to establish his own (begun in the same year The Solent was written), it appears Vaughan Williams’ mastery of the piano is evident in And ever winging up and up, personal musical language. He withdrew or destroyed imposingly to the line ‘And on its limitless, heaving breast, the this Fantasia and in the concerto he wrote for the Our valley is his golden cup many works from that period, with the notable exception ships’. -

Come, Thou Holy Spirit Anthem for Whitsuntide by Alan Gray VOCAL / ORGAN SCORE 2

1 Come, thou holy spirit Anthem for Whitsuntide By Alan Gray VOCAL / ORGAN SCORE 2 This score is in the Public Domain and has No Copyright under United States law. Anyone is welcome to make use of it for any purpose. Decorative images on this score are also in the Public Domain and have No Copyright under United States law. No determination was made as to the copyright status of these materials under the copyright laws of other countries. They may not be in the Public Domain under the laws of other countries. EHMS makes no warranties about the materials and cannot guarantee the accuracy of this Rights Statement. You may need to obtain other permissions for your intended use. For example, other rights such as publicity, privacy or moral rights may limit how you may use the material. You are responsible for your own use. http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/NoC-US/1.0/ Text written for this score, including project information and descriptions of individual works does have a new copyright, but is shared for public reuse under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0 International) license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Cover Image: “Pentecostés” by Juan Bautista Mayno, 1615/1620 (Museo del Prado) 3 The “renaissance” in English music is generally agreed to have started in the late Victorian period, beginning roughly in 1880. Public demand for major works in support of the annual choral festivals held throughout England at that time was considerable which led to the creation of many large scale works for orchestra with soloists and chorus.