I Muse and Method in the Songs of Hamilton Harty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Moore, Whose Patri- Manuscript Facsimiles and Musical Files, Otic-Imbued Writings Earned Him the with Commentary,” He Said

cc Page 24 Echo Lifestyle Ireland’s Minstrel Boy gets his encore By Michael P. Quinlin [email protected] William Blake. Phase one of the Moore project is slat- BOSTON — Ireland’s first mega star ed to go live this November, when the wrote poetry, history tomes and political Hypermedia Archive will be launched polemics that made him the talk of the at a conference in Galway, according to town in his native Dublin as well as in Ryder. London, Boston and New York. “By next year, we should have all the We’re not talking about Bono here, ‘Irish Melodies’ available online as texts, but rather Thomas Moore, whose patri- manuscript facsimiles and musical files, otic-imbued writings earned him the with commentary,” he said. The interest in Moore is enhanced by www.irishecho.com / Irish Echo May 21-27, 2008 titles Bard of Erin and Ireland’s National Poet. two new biographies, including one It was Moore’s lyrics to ancient Irish published last month by Ronan Kelly airs that brought him fame and notoriety entitled, “The Bard of Erin: the Life of during his lifetime and beyond. His Thomas Moore,” which Ryder says is famous collection, “Moore’s Melodies,” superb. was admired by the likes of Beethoven Like Ryder, Professor Flannery in and Lord Byron, and translated into six Atlanta never lost faith in Moore’s languages. importance in Irish history as a song- “Moore’s Melodies” was a ten-vol- writer, a literary influence and a nation- ume set of 124 songs published between alist figure. -

1St First Society Handbook AFB Album of Favorite Barber Shop Ballads, Old and Modern

1st First Society Handbook AFB Album of Favorite Barber Shop Ballads, Old and Modern. arr. Ozzie Westley (1944) BPC The Barberpole Cat Program and Song Book. (1987) BB1 Barber Shop Ballads: a Book of Close Harmony. ed. Sigmund Spaeth (1925) BB2 Barber Shop Ballads and How to Sing Them. ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1940) CBB Barber Shop Ballads. (Cole's Universal Library; CUL no. 2) arr. Ozzie Westley (1943?) BC Barber Shop Classics ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1946) BH Barber Shop Harmony: a Collection of New and Old Favorites For Male Quartets. ed. Sigmund Spaeth. (1942) BM1 Barber Shop Memories, No. 1, arr. Hugo Frey (1949) BM2 Barber Shop Memories, No. 2, arr. Hugo Frey (1951) BM3 Barber Shop Memories, No. 3, arr, Hugo Frey (1975) BP1 Barber Shop Parade of Quartet Hits, no. 1. (1946) BP2 Barber Shop Parade of Quartet Hits, no. 2. (1952) BP Barbershop Potpourri. (1985) BSQU Barber Shop Quartet Unforgettables, John L. Haag (1972) BSF Barber Shop Song Fest Folio. arr. Geoffrey O'Hara. (1948) BSS Barber Shop Songs and "Swipes." arr. Geoffrey O'Hara. (1946) BSS2 Barber Shop Souvenirs, for Male Quartets. New York: M. Witmark (1952) BOB The Best of Barbershop. (1986) BBB Bourne Barbershop Blockbusters (1970) BB Bourne Best Barbershop (1970) CH Close Harmony: 20 Permanent Song Favorites. arr. Ed Smalle (1936) CHR Close Harmony: 20 Permanent Song Favorites. arr. Ed Smalle. Revised (1941) CH1 Close Harmony: Male Quartets, Ballads and Funnies with Barber Shop Chords. arr. George Shackley (1925) CHB "Close Harmony" Ballads, for Male Quartets. (1952) CHS Close Harmony Songs (Sacred-Secular-Spirituals - arr. -

NABMSA Reviews a Publication of the North American British Music Studies Association

NABMSA Reviews A Publication of the North American British Music Studies Association Vol. 5, No. 2 (Fall 2018) Ryan Ross, Editor In this issue: Ita Beausang and Séamas de Barra, Ina Boyle (1889–1967): A Composer’s Life • Michael Allis, ed., Granville Bantock’s Letters to William Wallace and Ernest Newman, 1893–1921: ‘Our New Dawn of Modern Music’ • Stephen Connock, Toward the Rising Sun: Ralph Vaughan Williams Remembered • James Cook, Alexander Kolassa, and Adam Whittaker, eds., Recomposing the Past: Representations of Early Music on Stage and Screen • Martin V. Clarke, British Methodist Hymnody: Theology, Heritage, and Experience • David Charlton, ed., The Music of Simon Holt • Sam Kinchin-Smith, Benjamin Britten and Montagu Slater’s “Peter Grimes” • Luca Lévi Sala and Rohan Stewart-MacDonald, eds., Muzio Clementi and British Musical Culture • Christopher Redwood, William Hurlstone: Croydon’s Forgotten Genius Ita Beausang and Séamas de Barra. Ina Boyle (1889-1967): A Composer’s Life. Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press, 2018. 192 pp. ISBN 9781782052647 (hardback). Ina Boyle inhabits a unique space in twentieth-century music in Ireland as the first resident Irishwoman to write a symphony. If her name conjures any recollection at all to scholars of British music, it is most likely in connection to Vaughan Williams, whom she studied with privately, or in relation to some of her friends and close acquaintances such as Elizabeth Maconchy, Grace Williams, and Anne Macnaghten. While the appearance of a biography may seem somewhat surprising at first glance, for those more aware of the growing interest in Boyle’s music in recent years, it was only a matter of time for her life and music to receive a more detailed and thorough examination. -

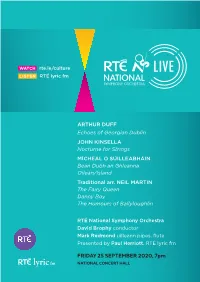

RTE NSO 25 Sept Prog.Qxp:Layout 1

WATCH rte.ie/culture LISTEN RTÉ lyric fm ARTHUR DUFF Echoes of Georgian Dublin JOHN KINSELLA Nocturne for Strings MÍCHEÁL Ó SÚILLEABHÁIN Bean Dubh an Ghleanna Oileán/Island Traditional arr. NEIL MARTIN The Fairy Queen Danny Boy The Humours of Ballyloughlin RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra David Brophy conductor Mark Redmond uilleann pipes, flute Presented by Paul Herriott, RTÉ lyric fm FRIDAY 25 SEPTEMBER 2020, 7pm NATIONAL CONCERT HALL 1 Arthur Duff 1899-1956 Echoes of Georgian Dublin i. In College Green ii. Song for Amanda iii. Minuet iv. Largo (The tender lover) v. Rigaudon Arthur Duff showed early promise as a musician. He was a chorister at Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral and studied at the Royal Irish Academy of Music, taking his degree in music at Trinity College, Dublin. He was later awarded a doctorate in music in 1942. Duff had initially intended to enter the Church of Ireland as a priest, but abandoned his studies in favour of a career in music, studying composition for a time with Hamilton Harty. He was organist and choirmaster at Christ Church, Bray, for a short time before becoming a bandmaster in the Army School of Music and conductor of the Army No. 2 band based in Cork. He left the army in 1931, at the same time that his short-lived marriage broke down, and became Music Director at the Abbey Theatre, writing music for plays such as W.B. Yeats’s The King of the Great Clock Tower and Resurrection, and Denis Johnston’s A Bride for the Unicorn. The Abbey connection also led to the composition of one of Duff’s characteristic works, the Drinking Horn Suite (1953 but drawing on music he had composed twenty years earlier as a ballet score). -

Séamas De Barra

1 Séamas de Barra Aloys Fleischmann Field Day Music Aloys Fleischmann (1910–92) was a key figure in the musical General Editors: Séamas de Barra and Patrick Zuk Séamas de Barra life of twentieth-century Ireland. Séamas de Barra presents an authoritative and insightful account of Fleischmann’s career 1. Aloys Fleischmann (2006), Séamas de Barra as a composer, conductor, teacher and musicologist, situating 2. Raymond Deane (2006), Patrick Zuk his achievements in wider social and intellectual contexts, and paying particular attention to his lifelong engagement Among forthcoming volumes are studies of Ina Boyle, Seóirse with Gaelic culture and his attempts to forge a distinctively Bodley, Michele Esposito and James Wilson. Aloys Irish music. Fleischmann Séamas de Barra is a composer and a musicologist. Music/Contemporary Ireland FIELD DAY PUBLICATIONS MUSIC 1 Séamas de Barra Aloys Fleischmann Field Day Music Aloys Fleischmann (1910–92) was a key figure in the musical General Editors: Séamas de Barra and Patrick Zuk Séamas de Barra life of twentieth-century Ireland. Séamas de Barra presents an authoritative and insightful account of Fleischmann’s career 1. Aloys Fleischmann (2006), Séamas de Barra as a composer, conductor, teacher and musicologist, situating 2. Raymond Deane (2006), Patrick Zuk his achievements in wider social and intellectual contexts, and paying particular attention to his lifelong engagement Among forthcoming volumes are studies of Ina Boyle, Seóirse with Gaelic culture and his attempts to forge a distinctively Bodley, Michele Esposito and James Wilson. Aloys Irish music. Fleischmann Séamas de Barra is a composer and a musicologist. Music/Contemporary Ireland FIELD DAY PUBLICATIONS MUSIC Aloys Fleischmann i ii Aloys Fleischmann Aloys Fleischmann Aloys Fleischmann Aloys Fleischmann Séamas de Barra Field Day Music 1 Series Editors: Séamas de Barra and Patrick Zuk Field Day Publications Dublin, 2006 Séamas de Barra has asserted his right under the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000, to be identified as the author of this work. -

YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares Beside the Edmund Dulac Memorial Stone to W

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/194 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the same series YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 1, 2 Edited by Richard J. Finneran YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 3-8, 10-11, 13 Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS AND WOMEN: YEATS ANNUAL No. 9: A Special Number Edited by Deirdre Toomey THAT ACCUSING EYE: YEATS AND HIS IRISH READERS YEATS ANNUAL No. 12: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould and Edna Longley YEATS AND THE NINETIES YEATS ANNUAL No. 14: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS’S COLLABORATIONS YEATS ANNUAL No. 15: A Special Number Edited by Wayne K. Chapman and Warwick Gould POEMS AND CONTEXTS YEATS ANNUAL No. 16: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould INFLUENCE AND CONFLUENCE: YEATS ANNUAL No. 17: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares beside the Edmund Dulac memorial stone to W. B. Yeats. Roquebrune Cemetery, France, 1986. Private Collection. THE LIVING STREAM ESSAYS IN MEMORY OF A. NORMAN JEFFARES YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 A Special Issue Edited by Warwick Gould http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2013 Gould, et al. (contributors retain copyright of their work). The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text. -

Austin Clarke Papers

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 83 Austin Clarke Papers (MSS 38,651-38,708) (Accession no. 5615) Correspondence, drafts of poetry, plays and prose, broadcast scripts, notebooks, press cuttings and miscellanea related to Austin Clarke and Joseph Campbell Compiled by Dr Mary Shine Thompson 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 7 Abbreviations 7 The Papers 7 Austin Clarke 8 I Correspendence 11 I.i Letters to Clarke 12 I.i.1 Names beginning with “A” 12 I.i.1.A General 12 I.i.1.B Abbey Theatre 13 I.i.1.C AE (George Russell) 13 I.i.1.D Andrew Melrose, Publishers 13 I.i.1.E American Irish Foundation 13 I.i.1.F Arena (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.G Ariel (Periodical) 13 I.i.1.H Arts Council of Ireland 14 I.i.2 Names beginning with “B” 14 I.i.2.A General 14 I.i.2.B John Betjeman 15 I.i.2.C Gordon Bottomley 16 I.i.2.D British Broadcasting Corporation 17 I.i.2.E British Council 17 I.i.2.F Hubert and Peggy Butler 17 I.i.3 Names beginning with “C” 17 I.i.3.A General 17 I.i.3.B Cahill and Company 20 I.i.3.C Joseph Campbell 20 I.i.3.D David H. Charles, solicitor 20 I.i.3.E Richard Church 20 I.i.3.F Padraic Colum 21 I.i.3.G Maurice Craig 21 I.i.3.H Curtis Brown, publisher 21 I.i.4 Names beginning with “D” 21 I.i.4.A General 21 I.i.4.B Leslie Daiken 23 I.i.4.C Aodh De Blacam 24 I.i.4.D Decca Record Company 24 I.i.4.E Alan Denson 24 I.i.4.F Dolmen Press 24 I.i.5 Names beginning with “E” 25 I.i.6 Names beginning with “F” 26 I.i.6.A General 26 I.i.6.B Padraic Fallon 28 2 I.i.6.C Robert Farren 28 I.i.6.D Frank Hollings Rare Books 29 I.i.7 Names beginning with “G” 29 I.i.7.A General 29 I.i.7.B George Allen and Unwin 31 I.i.7.C Monk Gibbon 32 I.i.8 Names beginning with “H” 32 I.i.8.A General 32 I.i.8.B Seamus Heaney 35 I.i.8.C John Hewitt 35 I.i.8.D F.R. -

Passion and Intellect in the Music of Elizabeth Maconchy DBE (1907–1994)

Passion and Intellect in the Music of Elizabeth Maconchy DBE (1907–1994) Ailie Blunnie Thesis submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Master of Literature in Music Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare July 2010 Head of Department: Professor Fiona Palmer Supervisor: Dr Martin O’Leary Contents Acknowledgements i List of Abbreviations iii List of Illustrations iv Preface ix Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Part 1: The Early Years (1907–1939): Life and Historical Context 8 Early Education 10 Royal College of Music 11 Octavia Scholarship and Promenade Concert 17 New Beginnings: Leaving College 19 Macnaghten–Lemare Concerts 22 Contracting Tuberculosis 26 Part 2: Music of the Early Years 31 National Trends 34 Maconchy’s Approach to Composition 36 Overview of Works of this Period 40 The Land: Introduction 44 The Land: Movement I: ‘Winter’ 48 The Land: Movement II: ‘Spring’ 52 The Land: Movement III: ‘Summer’ 55 The Land: Movement IV: ‘Autumn’ 57 The Land: Summary 59 The String Quartet in Context 61 Maconchy’s String Quartets of the Period 63 String Quartet No. 1: Introduction 69 String Quartet No. 1: Compositional Procedures 74 String Quartet No. 1: Summary 80 String Quartet No. 2: Introduction 81 String Quartet No. 2: Movement I 83 String Quartet No. 2: Movement II 88 String Quartet No. 2: Movement III 91 String Quartet No. 2: Movement IV 94 Part 2: Summary 97 Chapter 3 Part 1: The Middle Years (1940–1969): Life and Historical Context 100 World War II 101 After the War 104 Accomplishments of this Period 107 Creative Dissatisfaction 113 Part 2: Music of the Middle Years 115 National Trends 117 Overview of Works of this Period 117 The String Quartet in Context 121 Maconchy’s String Quartets of this Period 122 String Quartet No. -

Final Appendices

Bibliography ADORNO, THEODOR W (1941). ‘On Popular Music’. On Record: Rock, Pop and the Written Word (ed. S Frith & A Goodwin, 1990): 301-314. London: Routledge (1publ. in Philosophy of Social Sci- ence, 9. 1941, New York: Institute of Social Research: 17-48). —— (1970). Om musikens fetischkaraktär och lyssnandets regression. Göteborg: Musikvetenskapliga in- stitutionen [On the fetish character of music and the regression of listening]. —— (1971). Sociologie de la musique. Musique en jeu, 02: 5-13. —— (1976a). Introduction to the Sociology of Music. New York: Seabury. —— (1976b) Musiksociologi – 12 teoretiska föreläsningar (tr. H Apitzsch). Kristianstad: Cavefors [The Sociology of Music – 12 theoretical lectures]. —— (1977). Letters to Walter Benjamin: ‘Reconciliation under Duress’ and ‘Commitment’. Aesthetics and Politics (ed. E Bloch et al.): 110-133. London: New Left Books. ADVIS, LUIS; GONZÁLEZ, JUAN PABLO (eds., 1994). Clásicos de la Música Popular Chilena 1900-1960. Santiago: Sociedad Chilena del Derecho de Autor. ADVIS, LUIS; CÁCERES, EDUARDO; GARCÍA, FERNANDO; GONZÁLEZ, JUAN PABLO (eds., 1997). Clásicos de la música popular chilena, volumen II, 1960-1973: raíz folclórica - segunda edición. Santia- go: Ediciones Universidad Católica de Chile. AHARONIÁN, CORIúN (1969a). Boom-Tac, Boom-Tac. Marcha, 1969-05-30. —— (1969b) Mesomúsica y educación musical. Educación artística para niños y adolescentes (ed. Tomeo). 1969, Montevideo: Tauro (pp. 81-89). —— (1985) ‘A Latin-American Approach in a Pioneering Essay’. Popular Music Perspectives (ed. D Horn). Göteborg & Exeter: IASPM (pp. 52-65). —— (1992a) ‘Music, Revolution and Dependency in Latin America’. 1789-1989. Musique, Histoire, Dé- mocratie. Colloque international organisé par Vibrations et l’IASPM, Paris 17-20 juillet (ed. A Hennion. -

Sir Hamilton Harty Music Collection

MS14 Harty Collection About the collection: This is a collection of holograph manuscripts of the composer and conductor, Sir Hamilton Harty (1879-1941) featuring full and part scores to a range of orchestral and choral pieces composed or arranged by Harty, c 1900-1939. Included in the collection are arrangements of Handel and Berlioz, whose performances of which Harty was most noted, and autograph manuscripts approx. 48 original works including ‘Symphony in D (Irish)’ (1915), ‘The Children of Lir’ (c 1939), ‘In Ireland, A Fantasy for flute, harp and small orchestra’ and ‘Quartet in F for 2 violins, viola and ‘cello’ for which he won the Feis Ceoil prize in 1900. The collection also contains an incomplete autobiographical memoir, letters, telegrams, photographs and various typescript copies of lectures and articles by Harty on Berlioz and piano accompaniment, c 1926 – c 1936. Also included is a set of 5 scrapbooks containing cuttings from newspapers and periodicals, letters, photographs, autographs etc. by or relating to Harty. Some published material is also included: Performance Sets (Appendix1), Harty Songs (MS14/11). The Harty Collection was donated to the library by Harty’s personal secretary and intimate friend Olive Baguley in 1946. She was the executer of his possessions after his death. In 1960 she received an honorary degree from Queen’s (Master of Arts) in recognition of her commitment to Harty, his legacy, and her assignment of his belongings to the university. The original listing was compiled in various stages by Declan Plumber -

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin To cite this version: Denis-Constant Martin. Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa. African Minds, Somerset West, pp.472, 2013, 9781920489823. halshs-00875502 HAL Id: halshs-00875502 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00875502 Submitted on 25 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Sounding the Cape Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin AFRICAN MINDS Published by African Minds 4 Eccleston Place, Somerset West, 7130, South Africa [email protected] www.africanminds.co.za 2013 African Minds ISBN: 978-1-920489-82-3 The text publication is available as a PDF on www.africanminds.co.za and other websites under a Creative Commons licence that allows copying and distributing the publication, as long as it is attributed to African Minds and used for noncommercial, educational or public policy purposes. The illustrations are subject to copyright as indicated below. Photograph page iv © Denis-Constant -

The Afterlives of the Irish Literary Revival

The Afterlives of the Irish Literary Revival Author: Dathalinn Mary O'Dea Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104356 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2014 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of English THE AFTERLIVES OF THE IRISH LITERARY REVIVAL a dissertation by DATHALINN M. O’DEA submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2014 © copyright by DATHALINN M. O’DEA 2014 Abstract THE AFTERLIVES OF THE IRISH LITERARY REVIVAL Director: Dr. Marjorie Howes, Boston College Readers: Dr. Paige Reynolds, College of the Holy Cross and Dr. Christopher Wilson, Boston College This study examines how Irish and American writing from the early twentieth century demonstrates a continued engagement with the formal, thematic and cultural imperatives of the Irish Literary Revival. It brings together writers and intellectuals from across Ireland and the United States – including James Joyce, George William Russell (Æ), Alice Milligan, Lewis Purcell, Lady Gregory, the Fugitive-Agrarian poets, W. B. Yeats, Harriet Monroe, Alice Corbin Henderson, and Ezra Pound – whose work registers the movement’s impact via imitation, homage, adaptation, appropriation, repudiation or some combination of these practices. Individual chapters read Irish and American writing from the period in the little magazines and literary journals where it first appeared, using these publications to give a material form to the larger, cross-national web of ideas and readers that linked distant regions.