Managing the U.S.-Japan Alliance: an Examination of Structural Linkages in the Security Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fukushima Nuclear Accident and Crisis Management

e Fukushima Nuclearand Crisis Accident Management e Fukushima The Fukushima Nuclear Accident and Crisis Management — Lessons for Japan-U.S. Alliance Cooperation — — Lessons for Japan-U.S. Alliance Cooperation — — Lessons for Japan-U.S. September, 2012 e Sasakawa Peace Foundation Foreword This report is the culmination of a research project titled ”Assessment: Japan-US Response to the Fukushima Crisis,” which the Sasakawa Peace Foundation launched in July 2011. The accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant that resulted from the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 11, 2011, involved the dispersion and spread of radioactive materials, and thus from both the political and economic perspectives, the accident became not only an issue for Japan itself but also an issue requiring international crisis management. Because nuclear plants can become the target of nuclear terrorism, problems related to such facilities are directly connected to security issues. However, the policymaking of the Japanese government and Japan-US coordination in response to the Fukushima crisis was not implemented smoothly. This research project was premised upon the belief that it is extremely important for the future of the Japan-US relationship to draw lessons from the recent crisis and use that to deepen bilateral cooperation. The objective of this project was thus to review and analyze the lessons that can be drawn from US and Japanese responses to the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, and on the basis of these assessments, to contribute to enhancing the Japan-US alliance’s nuclear crisis management capabilities, including its ability to respond to nuclear terrorism. -

Daily Bonds, Stocks, & Currency

DAILY BONDS, STOCKS, & CURRENCY COMMENTARY Wednesday December 23, 2020 BONDS COMMENTARY 12/23/20 We expect rallies off scheduled data but doubt the gains will hold OVERNIGHT CHANGES THROUGH 3:16 AM (CT): BONDS -0 Overnight treasury prices extended yesterday's bounce but ultimately failed to hold the gains and have settled back into negative territory early today. We suspect the volatility in treasuries was the result of news that the President might reject the intensely negotiated stimulus deal because direct payments were not sufficient. While not a recent definitive impact on treasury prices, it would also appear as if yet another major junction looms from the exit negotiations with both sides the table committed to one last attempt to solve the divorce before it is forced upon the parties. While the markets are likely to view the US durable goods order as the primary release of the day, (early due to holiday) initial and ongoing claims data figures will add to the potential volatility in the 7:30 release window. On the other hand, traders should acknowledge yesterday's significant jump in quarterly PCE readings were the highest since the second quarter of 2011 and that could be an early warning sign that deflation is being replaced with reflation. Therefore, the monthly PCE index this morning might be very important measure to watch, especially with predictions for that reading only expected to post a fractional gain! Given the markets inability to rally off weak scheduled data recently, we would suggest traders wait for a rally to the vicinity of 174-00 to sell March bonds and or a rally to 138-07 to get short March Notes. -

Prints and Their Production; a List of Works in the New York Public Library

N E UC-NRLF PRINTS AND THEIR PRODUCTION A LIST OF WORKS IN THE NEW YORK PUPUBLIC LIBRARY COMPILED BY FRANK WEITENKAMPF, L.H.D. CHIEF, ART AND PRINTS DIVISION NEW YORK PUBLIC LIB-RARY 19 l6 ^4^ NOTE to This list contains the titles of works relating owned the prints and their production, by Reference on Department of The New York Public Library in the Central Build- November 1, 1915. They are Street. ing, at Fifth Avenue and Forty-second Reprinted September 1916 FROM THE Bulletin of The New York Public Library November - December 1915 form p-02 [ix-20-lfl 25o] CONTENTS I. Prints as Art Products PAGE - - Bibliography 1 Individual Artists - - 2>7 - 2 General and Miscellaneous Works Special Processes - - _ . 79 Periodicals and Societies - - - 3 Etching - - - - - - 79 Processes: Line Engraving and Proc- Handbooks (Technical) - - 79 esses IN General - - - 4 History - 81 Regional - ----- 82 Handbooks for the Student and Col- (Subdivided lector ------ 6 by countries.) Stipple 84 Sales and Prices: General Works - 7 Mezzotint - 84 Extra-Illustration - - - - 8 Aquatint 86 Care of Prints ----- 8 Dotted Prints (Maniere Criblee; History (General) . - _ _ 9 Schrotblatter) - - - - 86 Nielli -_--__ H Wood Engraving - - - - 86 Paste Prints ("Teigdrucke") - - 12 Handbooks (Technical) - - 87 Reproductions of Prints - - - 12 History ------ 87 History (Regional) - - - - 13 Block-books ----- 89 (Subdivided by countries; includes History: Regional- - - - 90 Japanese prints.) (Subdivided by countries.) Dictionaries of Artists - - - 26 Lithography ----- 91 Exhibitions (General and Miscel- Handbooks (Technical) - - 91 laneous) 29 History ------ 94 Collections (Public) - - - - 31 Regional - 95 (Subdivided by countries.) (Subdivided by countries.) Collections (Private) - - - - 34 Color Prints ----- 96 II. -

Military Use Handbook

National Interagency Fire Center Military Use Handbook 2021 This publication was produced by the National Interagency Coordination Center (NICC), located at the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC), Boise, Idaho. This publication is also available on the Internet at http://www.nifc.gov/nicc/logistics/references.htm. MILITARY USE HANDBOOK 2021 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. ………………… ..................................................................................................................................................... CHAPTER 10 – GENERAL ........................................................................................................ 1 10.1 Purpose ............................................................................................................... 1 10.2 Overview .............................................................................................................. 1 10.3 Ordering Requirements and Procedures .............................................................. 1 10.4 Authorities/Responsibilities .................................................................................. 2 10.5 Billing Procedures ................................................................................................ 3 CHAPTER 20 – RESOURCE ORDERING PROCEDURES FOR MILITARY ASSETS ............... 4 20.1 Ordering Process ................................................................................................. 4 20.2 Demobilization -

Annual Report 2015 2015 Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company, Year Ended March 31, 2015

Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company Meiji Yasuda Annual Report Annual Report 2015 2015 Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company, Year ended March 31, 2015 1-1, Marunouchi 2-chome, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-0005, Japan Phone:+81-3-3283-8293 Fax:+81-3-3215-8123 Printed in Japan International Directory (As of March 31, 2015) TUiR Warta S.A. Pacific Guardian Life Insurance Company, Limited Seoul Representative Office Southern California Office Beijing Representative Office TU Europa S.A. Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company Meiji Yasuda America Incorporated Meiji Yasuda Realty USA Incorporated Frankfurt Representative Office Founder Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Co., Ltd. Meiji Yasuda Europe Limited Meiji Yasuda Asia Limited Thai Life Insurance Public Company Limited Pacific Guardian Life Insurance Company, Limited PT Avrist Assurance Headquarters Representative Offices Subsidiaries Affiliates Headquarters Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company 1-1, Marunouchi 2-chome, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-0005, Japan Phone:+81-3-3283-8293 Fax:+81-3-3215-8123 Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company Representative Frankfurt Representative Office Beijing Representative Office Goethestrasse 7, 60313 Frankfurt am Main, Germany Room 6003, 6th Floor, Changfugong Office Building, Offices Phone:+49-69-748000 Fax:+49-69-748021 26 Jianguomen Wai Avenue, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100022, China Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company Phone:+86-10-6513-9815 Fax:+86-10-6513-9818 Seoul Representative Office The Seoul Shinmun Daily (Korea Press Center) Bldg., 9th Floor, 124 Sejong-daero, Jung-gu, Seoul 100-745, Korea Contents Phone:+82-2-723-9111 Fax:+82-2-723-6489 Subsidiaries Pacific Guardian Life Insurance Company, Limited Pacific Guardian Life Insurance Company, Limited Corporate Profile 2 Risk Management Structure 28 1440 Kapiolani Boulevard, Suite 1700, Honolulu, Hawaii Southern California Office 96814, U.S.A. -

Why Japan Supports Whaling

An edited version of this paper has been accepted for publication in the Journal of International Wildlife and Policy WHY JAPAN SUPPORTS WHALING Keiko Hirata* 1. INTRODUCTION Japan is one of the few states in the world that adamantly supports whaling. For decades, Tokyo has steadfastly maintained its right to whale and has aggressively lobbied the International Whaling Commission (IWC) for a resumption of commercial whaling. Japan’s pro-whaling stance has invited strong international criticism from both environmental groups and Western governments, many of which view Tokyo as obstructing international efforts to protect whales. Why has Japan adhered to a pro-whaling policy that has brought the country international condemnation? Its defiant pro-whaling stance is not consistent with its internationally cooperative position on other environmental matters. For the past decade, Tokyo has been a key player in international environmental regimes, such as those to combat ozone depletion and global warming.1 If Japan is serious about environmental protection and desires to play a role as a ‘green contributor,’2 why hasn’t it embraced the anti-whaling norm, 3 thereby joining other states in wildlife protection and assuming a larger role in global environmental leadership? *Research Fellow, Center for the Study of Democracy, University of California, Irvine, California, USA. E-mail: [email protected]. 1 Isao Miyaoka, 1980s and Early 1990s: Changing from an Eco-outlaw to a Green Contributor, 16 NEWSL. INST. SOC. SCI. U. TOKYO, 7-10 (1999). 2 Id. at 7. 3 Robert L. Friedheim, Introduction: The IWC as a Contested Regime, in TOWARD A SUSTAINABLE WHALING REGIME, 1-45 (Robert L. -

Expert Voices on Japan Security, Economic, Social, and Foreign Policy Recommendations

Expert Voices on Japan Security, Economic, Social, and Foreign Policy Recommendations U.S.-Japan Network for the Future Cohort IV Expert Voices on Japan Security, Economic, Social, and Foreign Policy Recommendations U.S.-Japan Network for the Future Cohort IV Arthur Alexander, Editor www.mansfieldfdn.org The Maureen and Mike Mansfield Foundation, Washington, D.C. ©2018 by The Maureen and Mike Mansfield Foundation All rights reserved. Published in the United States of America Library of Congress Control Number: 2018942756 The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Maureen and Mike Mansfield Foundation or its funders. Contributors Amy Catalinac, Assistant Professor, New York University Yulia Frumer, Assistant Professor, Johns Hopkins University Robert Hoppens, Associate Professor, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Nori Katagiri, Assistant Professor, Saint Louis University Adam P. Liff, Assistant Professor, Indiana University Ko Maeda, Associate Professor, University of North Texas Reo Matsuzaki, Assistant Professor, Trinity College Matthew Poggi Michael Orlando Sharpe, Associate Professor, City University of New York Jolyon Thomas, Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania Kristin Vekasi, Assistant Professor, University of Maine Joshua W. Walker, Managing Director for Japan and Head of Global Strategic Initiatives, Office of the President, Eurasia Group U.S.-Japan Network for the Future Advisory Committee Dr. Susan J. Pharr, Edwin O. Reischauer Professor -

Sanctuary Lost: the Air War for ―Portuguese‖ Guinea, 1963-1974

Sanctuary Lost: The Air War for ―Portuguese‖ Guinea, 1963-1974 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Martin Hurley, MA Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Professor John F. Guilmartin, Jr., Advisor Professor Alan Beyerchen Professor Ousman Kobo Copyright by Matthew Martin Hurley 2009 i Abstract From 1963 to 1974, Portugal and the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde, or PAIGC) waged an increasingly intense war for the independence of ―Portuguese‖ Guinea, then a colony but today the Republic of Guinea-Bissau. For most of this conflict Portugal enjoyed virtually unchallenged air supremacy and increasingly based its strategy on this advantage. The Portuguese Air Force (Força Aérea Portuguesa, abbreviated FAP) consequently played a central role in the war for Guinea, at times threatening the PAIGC with military defeat. Portugal‘s reliance on air power compelled the insurgents to search for an effective counter-measure, and by 1973 they succeeded with their acquisition and employment of the Strela-2 shoulder-fired surface-to-air missile, altering the course of the war and the future of Portugal itself in the process. To date, however, no detailed study of this seminal episode in air power history has been conducted. In an international climate plagued by insurgency, terrorism, and the proliferation of sophisticated weapons, the hard lessons learned by Portugal offer enduring insight to historians and current air power practitioners alike. -

Reform in Late Occupation Japan the 1950 Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties

Reform in Late Occupation Japan The 1950 Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties Ioan Trifu∗ I. Introduction II. The Situation of Japanese Cultural Heritage in the Aftermath of World War II 1. The Prewar Legislation Regarding the Protection of Japanese Cultural Heritage 2. World War II and Japan’s Cultural Heritage 3. The Occupation Period: Political, Economic and Social Threats to Japanese Cultural Heritage III. Reconsidering the Protection of Cultural Heritage in Japan 1. Collaboration and Emergencies: The Joint Efforts of the Early Occupation Period 2. Tensions and Oppositions: Defending the Occupation’s Objectives IV. A Few Concessions and Numerous Ambitions: The Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties in 1950 1. Compromising in a Shifting Context: The 1949–1950 Legislative Process 2. The 1950 Law: A New Cultural Heritage System for a New Japanese Nation? V. Conclusion I. INTRODUCTION For almost seven years (1945–1952) after the end of World War II, Japan was nominally under control of the Allied Occupation Forces, while it was the U.S. which led the Occupation de facto. Beginning with the first U.S. troops landing in Japan in late August 1945 and more officially with the Japanese capitulation of 2 September 1945, the Occupation of the country lasted until the signature of the San Francisco Peace Treaty on 28 April 1952. In October 1945, the General Headquarters/Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (GHQ/SCAP, hereinafter SCAP),1 a new civil organiza- ∗ Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Johann Wolfgang Goethe University Frankfurt am Main. The author gratefully acknowledges the generous funding support for this publi- cation provided by the Volkswagen Foundation, issued within its initiative “Key Is- sues for Research and Society” for the research project “Protecting the Weak: En- tangled processes of framing, mobilization and institutionalization in East Asia” (AZ 87 382) at the Interdisciplinary Centre for East Asian Studies (IZO), Goethe University, Frankfurt/Main. -

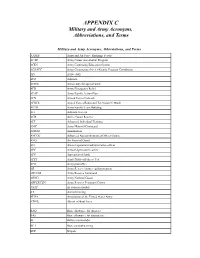

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

Japan's New Defense Establishment

JAPAN’S NEW DEFENSE ESTABLISHMENT: INSTITUTIONS, CAPABILITIES, AND IMPLICATIONS Yuki Tatsumi and Andrew L. Oros Editors March 2007 ii | JAPAN’S NEW DEFENSE ESTABLISHMENT Copyright ©2007 The Henry L. Stimson Center ISBN: 0-9770023-5-7 Photos by US Government and Ministry of Defense in Japan. Cover design by Rock Creek Creative. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from The Henry L. Stimson Center. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street, NW 12th Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone: 202-223-5956 fax: 202-238-9604 www.stimson.org YUKI TATSUMI AND ANDREW L. OROS | iii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................... v Preface ............................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements...........................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1: JAPAN’S EVOLVING DEFENSE ESTABLISHMENT .......................... 9 CHAPTER 2: SELF DEFENSE FORCES TODAY— BEYOND AN EXCLUSIVELY DEFENSE –ORIENTED POSTURE? ........................... 23 CHAPTER 3: THE LEGAL AND POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT SURROUNDING THE SELF-DEFENSE FORCES’ OVERSEAS DEPLOYMENTS ......................................... 47 CHAPTER 4: THE UNITED STATES AND “ALLIANCE” ROLE IN JAPAN’S -

World's Giants Make a Landfall in Japan – the Changing Japanese

COVER STORY • 8 World’s Giants Make a Landfall in Japan – The Changing Japanese M&A Market – By Takahashi Naoto APAN’S stock market enjoyed a and food maker RJR Nabisco Inc. for Critical of Vulture Funds, Placing J boom in the fall of 2005 for the first $25 billion. Founded in 1976, KKR Stress on Reconciliation time in many years. Keeping pace with racked up profits in the United States rising stock prices, Japan’s corporate and moved into Europe in the latter half Both KKR and AlixPartners are not merger and acquisition (M&A) market of the 1990s. Its next target was Japan eager about bad-debt disposal business- was on a course of expansion. A sym- where the investment climate saw an es. They also prefer reconciliation with bolic episode is the landfall of a major improvement thanks to the relaxation of existing managers and employees to hos- foreign investment fund and a corporate government controls and the active tile takeovers. rehabilitation consultant in Japan. stock market. Bad-debt disposal deals in Japan got Behind the advent of these “giants in the Justin Reizes, chief operations man- into full swing after a series of collapses world” was a change in the Japanese ager in Asia, explained KKR’s advance to of major financial houses like Yamaichi M&A market, which traditionally had Japan, saying the country’s M&A mar- Securities and the Long-Term Credit focused on the reconstruction of bad- ket is still smaller than its US and Bank of Japan (LTCB) in the latter half of debt corporations.