Why Japan Supports Whaling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History-Of-Whaling-Museum.Pdf

WHALING MUSEUM Hadwen & Barney Oil and Candle Factory as the Whaling Museum, 1967 JACK E. BOUCHER, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, PRINTS AND PHOTOGRAPHS DIVISION, HABS MA-908-2 100 Nantucket Historical Association WHALING MUSEUM Whaling Museum The Whaling Museum is the flagship site of the Nantucket Historical Association’s fleet of properties. From its origin in 1930 in the Hadwen ADDRESS & Barney Oil and Candle Factory, 13–15 Broad Street where the story of the industry that TH made Nantucket a celebrated place CONSTRUCTED . BIKE PA CLIFF CLIFF RD RD. BIKE Hulbert Ave. PA was told THthrough a collection of whal- Hadwen & Barney Oil ing implements, to its twenty-first-cen - and Candle Factory Civil War Brant Point Monument Tristram Con East Lincoln Ave. tury reinterpretation andHomesite expansion, Marker the 1847 W illard St Wa museum has consistentlyCli Road been a major PeterCornish Foulger St Museum N. Beach St . lsh St Swain St attraction for residents and visitors. 1971 . Easton Street . OldestWilliam House Hadwen and Nathaniel Whaling Museum N & Kitchen orth Ave. N. Centre St Way BarneyGarden were partners in one of the larg- 2005. Kite Hill MacKay Way Chester St est whale-oil manufacturing firms on Harborview S. Beach St Nantucket Harbor . N. Water St theSunset island Hill inLane the mid-nineteenth. cen- West Chester St tury, Hadwen & Barney. In 1848, they . North Liberty St . Sea St . Steamboat purchased the oil and candle factory Centre St NHA Whaling Museum Step Ln. Wharf Wyers Way Franklin St. Lily Pond Park & Museum Shop building on Broad Street at the head Ash St. -

Educator's Guide

Educator’s Guide Inside: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources • Standards Correlation • Glossary The Museum gratefully acknowledges the sdnat.org/whales County of San Diego and the City of San Diego Commission for Arts and Culture. ESSENTIAL Questions What is a whale? Many populations remain endangered. National and intergovernmental organizations collaborate to establish Whales are mammals; they breathe air and live their and enforce regulations that protect whale populations, whole lives in water. People often use the word “whale” to and some are showing recovery from whaling. The most refer to large species like sperm and humpback whales, effective whale protection programs involve the whole life but dolphins and porpoises are also whales since they’re cycle, from monitoring migration routes to conserving all members of the order Cetacea. Cetaceans evolved important breeding habitats and feeding grounds. from hoofed animals that walked on four legs, and their closest living relatives are hippos. Living whales are divided into two groups: baleen whales (Mysticeti, or How do scientists study whales? filter feeders) and toothed whales (Odontoceti, which Many kinds of scientists — conservation biologists, hunt larger prey). Whales inhabit all of the world’s major paleontologists, taxonomists, anatomists, ecologists, oceans, and even some of its rivers. Some species are geneticists — work together to learn more about these widespread, while others are localized. Many migrate magnificent creatures. Fossil specimens provide a long distances, with some species feeding in polar glimpse back some 50 million years, to whales’ waters and mating in warmer ones during the winter land-dwelling ancestors. -

Daily Bonds, Stocks, & Currency

DAILY BONDS, STOCKS, & CURRENCY COMMENTARY Wednesday December 23, 2020 BONDS COMMENTARY 12/23/20 We expect rallies off scheduled data but doubt the gains will hold OVERNIGHT CHANGES THROUGH 3:16 AM (CT): BONDS -0 Overnight treasury prices extended yesterday's bounce but ultimately failed to hold the gains and have settled back into negative territory early today. We suspect the volatility in treasuries was the result of news that the President might reject the intensely negotiated stimulus deal because direct payments were not sufficient. While not a recent definitive impact on treasury prices, it would also appear as if yet another major junction looms from the exit negotiations with both sides the table committed to one last attempt to solve the divorce before it is forced upon the parties. While the markets are likely to view the US durable goods order as the primary release of the day, (early due to holiday) initial and ongoing claims data figures will add to the potential volatility in the 7:30 release window. On the other hand, traders should acknowledge yesterday's significant jump in quarterly PCE readings were the highest since the second quarter of 2011 and that could be an early warning sign that deflation is being replaced with reflation. Therefore, the monthly PCE index this morning might be very important measure to watch, especially with predictions for that reading only expected to post a fractional gain! Given the markets inability to rally off weak scheduled data recently, we would suggest traders wait for a rally to the vicinity of 174-00 to sell March bonds and or a rally to 138-07 to get short March Notes. -

Prints and Their Production; a List of Works in the New York Public Library

N E UC-NRLF PRINTS AND THEIR PRODUCTION A LIST OF WORKS IN THE NEW YORK PUPUBLIC LIBRARY COMPILED BY FRANK WEITENKAMPF, L.H.D. CHIEF, ART AND PRINTS DIVISION NEW YORK PUBLIC LIB-RARY 19 l6 ^4^ NOTE to This list contains the titles of works relating owned the prints and their production, by Reference on Department of The New York Public Library in the Central Build- November 1, 1915. They are Street. ing, at Fifth Avenue and Forty-second Reprinted September 1916 FROM THE Bulletin of The New York Public Library November - December 1915 form p-02 [ix-20-lfl 25o] CONTENTS I. Prints as Art Products PAGE - - Bibliography 1 Individual Artists - - 2>7 - 2 General and Miscellaneous Works Special Processes - - _ . 79 Periodicals and Societies - - - 3 Etching - - - - - - 79 Processes: Line Engraving and Proc- Handbooks (Technical) - - 79 esses IN General - - - 4 History - 81 Regional - ----- 82 Handbooks for the Student and Col- (Subdivided lector ------ 6 by countries.) Stipple 84 Sales and Prices: General Works - 7 Mezzotint - 84 Extra-Illustration - - - - 8 Aquatint 86 Care of Prints ----- 8 Dotted Prints (Maniere Criblee; History (General) . - _ _ 9 Schrotblatter) - - - - 86 Nielli -_--__ H Wood Engraving - - - - 86 Paste Prints ("Teigdrucke") - - 12 Handbooks (Technical) - - 87 Reproductions of Prints - - - 12 History ------ 87 History (Regional) - - - - 13 Block-books ----- 89 (Subdivided by countries; includes History: Regional- - - - 90 Japanese prints.) (Subdivided by countries.) Dictionaries of Artists - - - 26 Lithography ----- 91 Exhibitions (General and Miscel- Handbooks (Technical) - - 91 laneous) 29 History ------ 94 Collections (Public) - - - - 31 Regional - 95 (Subdivided by countries.) (Subdivided by countries.) Collections (Private) - - - - 34 Color Prints ----- 96 II. -

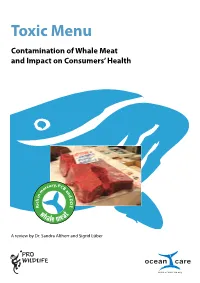

Toxic Menu – Contamination of Whale Meat

Toxic Menu Contamination of Whale Meat and Impact on Consumers’ Health ry, P rcu CB e a m n d n i D h D c i T . R wh at ale me A review by Dr. Sandra Altherr and Sigrid Lüber Baird‘s beaked whale, hunted and consumed in Japan, despite high burdens of PCB and mercury © Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) © 2009, 2012 (2nd edition) Title: Jana Rudnick (Pro Wildlife), Photo from EIA Text: Dr. Sandra Altherr (Pro Wildlife) and Sigrid Lüber (OceanCare) Pro Wildlife OceanCare Kidlerstr. 2, D-81371 Munich, Germany Oberdorfstr. 16, CH-8820 Wädenswil, Switzerland Phone: +49(089)81299-507 Phone: +41 (044) 78066-88 [email protected] [email protected] www.prowildlife.de www.oceancare.org Acknowledgements: The authors want to thank • Claire Bass (World Society for the Protection of Animals, UK) • Sakae Hemmi (Elsa Nature Conservancy, Japan) • Betina Johne (Pro Wildlife, Germany) • Clare Perry (Environmental Investigation Agency, UK) • Annelise Sorg (Canadian Marine Environment Protection Society, Canada) and other persons, who want to remain unnamed, for their helpful contribution of information, comments and photos. - 2 - Toxic Menu — Contamination of Whale Meat and Impact on Consumers’ Health Content 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 2. Contaminants and pathogens in whales ....................................................................................................... -

Annual Report 2015 2015 Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company, Year Ended March 31, 2015

Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company Meiji Yasuda Annual Report Annual Report 2015 2015 Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company, Year ended March 31, 2015 1-1, Marunouchi 2-chome, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-0005, Japan Phone:+81-3-3283-8293 Fax:+81-3-3215-8123 Printed in Japan International Directory (As of March 31, 2015) TUiR Warta S.A. Pacific Guardian Life Insurance Company, Limited Seoul Representative Office Southern California Office Beijing Representative Office TU Europa S.A. Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company Meiji Yasuda America Incorporated Meiji Yasuda Realty USA Incorporated Frankfurt Representative Office Founder Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Co., Ltd. Meiji Yasuda Europe Limited Meiji Yasuda Asia Limited Thai Life Insurance Public Company Limited Pacific Guardian Life Insurance Company, Limited PT Avrist Assurance Headquarters Representative Offices Subsidiaries Affiliates Headquarters Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company 1-1, Marunouchi 2-chome, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-0005, Japan Phone:+81-3-3283-8293 Fax:+81-3-3215-8123 Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company Representative Frankfurt Representative Office Beijing Representative Office Goethestrasse 7, 60313 Frankfurt am Main, Germany Room 6003, 6th Floor, Changfugong Office Building, Offices Phone:+49-69-748000 Fax:+49-69-748021 26 Jianguomen Wai Avenue, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100022, China Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company Phone:+86-10-6513-9815 Fax:+86-10-6513-9818 Seoul Representative Office The Seoul Shinmun Daily (Korea Press Center) Bldg., 9th Floor, 124 Sejong-daero, Jung-gu, Seoul 100-745, Korea Contents Phone:+82-2-723-9111 Fax:+82-2-723-6489 Subsidiaries Pacific Guardian Life Insurance Company, Limited Pacific Guardian Life Insurance Company, Limited Corporate Profile 2 Risk Management Structure 28 1440 Kapiolani Boulevard, Suite 1700, Honolulu, Hawaii Southern California Office 96814, U.S.A. -

Report of the EXPERT MEETING to DEVELOP TECHNICAL GUIDELINES to REDUCE BYCATCH of MARINE MAMMALS in CAPTURE FISHERIES

FIAO/R1289 (En) FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Report ISSN 2070-6987 Report of the EXPERT MEETING TO DEVELOP TECHNICAL GUIDELINES TO REDUCE BYCATCH OF MARINE MAMMALS IN CAPTURE FISHERIES Rome, Italy, 17−19 September 2019 Cover illustration: Alberto Gennari (2019) FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Report No. 1289 FIAO/R1289 (En) Report of the EXPERT MEETING TO DEVELOP TECHNICAL GUIDELINES TO REDUCE BYCATCH OF MARINE MAMMALS IN CAPTURE FISHERIES Rome, Italy, 17–19 September 2019 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2020 Required citation: FAO. 2020. Report of the Expert Meeting to Develop Technical Guidelines to Reduce Bycatch of Marine Mammals in Capture Fisheries. Rome, Italy, 17–19 September 2019. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Report No. 1289, Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/CA7620EN The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN: 978-92-5-132150-8 ISSN: 2070-6987 (print) © FAO, 2020 Some rights reserved. -

Number 30 June 2005 ISSN 1192-3539

Number 30 June 2005 ISSN 1192-3539 Editorial MAKAH TRIBE PURSUES RIGHT TO HUNT The Digest continues to provide news on whaling research to On February 14 2005, the Makah Indian tribe of Washington researchers and libraries in many countries, and we appreciate State filed an application with the National Oceanic and hearing from researchers regarding the work they are doing in Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) requesting a waiver of diverse study areas. We aim to publish information on whaling the take moratorium under the Marine Mammal Protection Act research carried out in the social sciences, history, archeology for a ceremonial and subsistence harvest of up to 20 gray and law, and in other relevant fields (such as, e.g., the whales in any 5-year period. performing and graphic arts). A glance at this issue of the Digest indicates that research on whaling in diverse research The filing of this application is the result of a series of federal fields continues, published and communicated at whaling court rulings in a lawsuit filed by the Fund for Animals and the symposia and workshops, and that whaling and whale cultures Humane Society of the United States on January 10, 2002. The continue in various countries and provide opportunities today most recent court decision on June 7, 2004 left the Makah with for those wanting to study in situ whaling. Readers are two alternatives: (1) comply with the court decision by (a) reminded that the INWR Website, www.ualberta.ca/~inwr/ preparing a full environmental impact statement (EIS) and (b) contains further information on whaling and whaling research, seek either a permit or a permit waiver under the Marine and useful links to other whaling research websites Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) for taking a quota of gray whales; or (2) appeal the court decision to the US Supreme LITTLE DIOMEDE ISLANDERS LAND SEASON’S Court. -

Expert Voices on Japan Security, Economic, Social, and Foreign Policy Recommendations

Expert Voices on Japan Security, Economic, Social, and Foreign Policy Recommendations U.S.-Japan Network for the Future Cohort IV Expert Voices on Japan Security, Economic, Social, and Foreign Policy Recommendations U.S.-Japan Network for the Future Cohort IV Arthur Alexander, Editor www.mansfieldfdn.org The Maureen and Mike Mansfield Foundation, Washington, D.C. ©2018 by The Maureen and Mike Mansfield Foundation All rights reserved. Published in the United States of America Library of Congress Control Number: 2018942756 The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Maureen and Mike Mansfield Foundation or its funders. Contributors Amy Catalinac, Assistant Professor, New York University Yulia Frumer, Assistant Professor, Johns Hopkins University Robert Hoppens, Associate Professor, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Nori Katagiri, Assistant Professor, Saint Louis University Adam P. Liff, Assistant Professor, Indiana University Ko Maeda, Associate Professor, University of North Texas Reo Matsuzaki, Assistant Professor, Trinity College Matthew Poggi Michael Orlando Sharpe, Associate Professor, City University of New York Jolyon Thomas, Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania Kristin Vekasi, Assistant Professor, University of Maine Joshua W. Walker, Managing Director for Japan and Head of Global Strategic Initiatives, Office of the President, Eurasia Group U.S.-Japan Network for the Future Advisory Committee Dr. Susan J. Pharr, Edwin O. Reischauer Professor -

On the Sperm Whale (Physeter Macrocephalus) Ecology, Sociality and Behavior Off Ischia Island (Italy): Patterns of Sound Production and Acoustically Measured Growth

DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL BIOLOGY “CHARLES DARWIN” SAPIENZA UNIVERSITY OF ROME PHD IN ENVIRONMENTAL AND EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY ANIMAL BIOLOGY CURRICULUM XXVIII CYCLE On the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) ecology, sociality and behavior off Ischia Island (Italy): patterns of sound production and acoustically measured growth by Daniela Silvia Pace Tutor: Prof. Giandomenico Ardizzone, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy External Reviewer: Prof. Gianni Pavan, University of Pavia, Italy Rome, November 2016 Table of contents _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ List of Figures List of Tables Goals and thesis outline Chapter 1 – Sperm whale biology 1.1 General anatomy ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 1 1.2 Abundance, distribution and movements ………………………………………………………………………….. 2 1.3 Reproduction and social structure ……………………………………………………………………………………. 5 1.4 Feeding and main prey …………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 1.5 Diving behavior …………………………………………………….…………………………………………………………. 8 1.6 Threats and conservation ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 9 Chapter 2 – Sperm whale acoustics 2.1 The spermaceti organ …………………………………………………………………………………………….……… 12 2.2 Click structure ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 14 2.3 Type of sounds ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 2.3.1 Usual clicks ………………………………………………………………………….…….………………..…… 16 2.3.2 Creaks …………………………………………………..……………………………………………………..…. 17 2.3.3 Codas …………………………………………….……………………………………………………………..… 19 -

Reform in Late Occupation Japan the 1950 Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties

Reform in Late Occupation Japan The 1950 Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties Ioan Trifu∗ I. Introduction II. The Situation of Japanese Cultural Heritage in the Aftermath of World War II 1. The Prewar Legislation Regarding the Protection of Japanese Cultural Heritage 2. World War II and Japan’s Cultural Heritage 3. The Occupation Period: Political, Economic and Social Threats to Japanese Cultural Heritage III. Reconsidering the Protection of Cultural Heritage in Japan 1. Collaboration and Emergencies: The Joint Efforts of the Early Occupation Period 2. Tensions and Oppositions: Defending the Occupation’s Objectives IV. A Few Concessions and Numerous Ambitions: The Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties in 1950 1. Compromising in a Shifting Context: The 1949–1950 Legislative Process 2. The 1950 Law: A New Cultural Heritage System for a New Japanese Nation? V. Conclusion I. INTRODUCTION For almost seven years (1945–1952) after the end of World War II, Japan was nominally under control of the Allied Occupation Forces, while it was the U.S. which led the Occupation de facto. Beginning with the first U.S. troops landing in Japan in late August 1945 and more officially with the Japanese capitulation of 2 September 1945, the Occupation of the country lasted until the signature of the San Francisco Peace Treaty on 28 April 1952. In October 1945, the General Headquarters/Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (GHQ/SCAP, hereinafter SCAP),1 a new civil organiza- ∗ Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Johann Wolfgang Goethe University Frankfurt am Main. The author gratefully acknowledges the generous funding support for this publi- cation provided by the Volkswagen Foundation, issued within its initiative “Key Is- sues for Research and Society” for the research project “Protecting the Weak: En- tangled processes of framing, mobilization and institutionalization in East Asia” (AZ 87 382) at the Interdisciplinary Centre for East Asian Studies (IZO), Goethe University, Frankfurt/Main. -

A Theory for the Function of the Spermaceti Organ of the Sperm Whale (Physeter Catodon L.)

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=19720017437 2020-03-23T13:22:20+00:00Z A Theory for the Function of the Spermaceti Organ of the Sperm Whale (Physeter catodon L.) KENNETH S. NORRIS Oceanic Znstitute and University of California, Los Angeles GEORGE W. HARVEY Oceanic Znstitute ITHIN THE SPERM WHALE FOREHEAD make diving possible by firmly closing the wlies the spermaceti organ, occupying outer and inner nasal passages.” They go on as much as 40 percent of the entire length of to 3ay : the whale. It is a huge, somewhat flattened, cone-shaped structure. It is covered dorsally We infer that its main function is to act as a force pump for the bony narial passages, and laterally by a thick wall of intermeshing drawing a great quantity of air into the ligamentous cables, many as thick as a man’s respiratory sacs and perhaps preventing the escape of air under the pressures of the great thumb. In the day of the hand whaler, this depths. It may also act in part as a hydro- stout outer structure was called “the case.” static organ since by severe contractions of part of its muscular sheath, the contained oil The organ is filled in life with as much as might be squeezed toward one end or the 1900 liters of a liquid, or semiliquid waxy oil, other, while the air sacs were being inflated, thus lightening the specific gravity of that the spermaceti-the material once so prized end and tending to alter the direction of for candles and illuminating oil.