The Case Study of a Tourism Destination in Ticino

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imp.Xtrix in Pdf 06

Hystrix It. J. Mamm. (n.s.) 18 (1) (2007): 39-55 THE BATS OF THE LAKE MAGGIORE PIEDMONT SHORE (NW ITALY) PAOLO DEBERNARDI, ELENA PATRIARCA Stazione Teriologica Piemontese S.Te.P., c/o Museo Civico di Storia Naturale, c.p. 89, 10022 Carmagnola (TO), Italy; e-mail: [email protected] Received 25 May 2006; accepted 23 February 2007 ABSTRACT - In the period 1999-2005 we carried out a bat survey along the Piedmont shore of Lake Maggiore (provinces of Verbania and Novara, NW Italy), in order to collect data on species distribution, with special reference to wetlands. A total of 155 potential roost sites were checked: natural or artificial underground sites (11%), bridges and boat basins (25%), churches (36%), cemeteries (12%) and other buildings (16%). Underground sites were visited both in summer and winter, the other sites only in summer. Mist-netting was performed in wetlands at sites located in the southern, central and northern parts of the lake area. Additional data were obtained by acoustic surveys and from the finding of dead or injured bats. We recorded at least 18 species and 79 roosts. Pipistrellus kuhlii and P. pipistrellus were the species most frequently observed roosting in buildings; Myotis daubentonii was the commonest species in bridges and boat basins. Such species were also the most frequently caught in mist-netting sessions. Three winter roosts (each used by 1-10 bats) and a nursery site used by species of major conservation concern (Habitats Directive, Annex II) were found. Annual counts of the maternity colony varied from 694 to 919 bats aged > 1 year, mainly M. -

Accord Des 11 Avril/14 Mai 1951 Entre Le Gouvernement Suisse Et Le

Traduction1 0.818.694.54 Accord entre le gouvernement suisse et le gouvernement italien concernant la translation de corps à travers la frontière dans les régions limitrophes Conclu les 11 avril/1er mai 1951 Entré en vigueur le 1er juillet 1951 Entre la légation de Suisse à Rome et le ministère italien des affaires étrangères a eu lieu en date des 11 avril/14 mai 1951 un échange de notes relatif à la translation de corps à travers la frontière dans les régions limitrophes. La note suisse – en traduc- tion française – a la teneur suivante: 1. L’arrangement international concernant le transport des corps conclu à Ber- lin le 10 février 19372 auquel ont adhéré soit l’Italie et la Suisse, prévoit à l’article 10 que ses dispositions ne s’appliquent pas au transport de corps s’effectuant dans les régions frontalières. Les deux gouvernements décident d’adopter à cet égard la procédure suivante. 2. Le trafic local dans les régions frontalières comprend en l’espèce une zone située des deux côtés de la frontière italo-suisse dans un rayon d’environ 10 km; la procédure relative au transport des corps dans les limites de cette zone s’applique aux localités indiquées dans les listes ci-jointes. 3. Les laissez-passer pour cadavres sont délivrés, du côte suisse, par les autori- tés cantonales et, du côté italien, par les autorités provinciales. En Suisse, le autorités compétentes sont, dans le canton des Grisons, les commissariats de district, dans le canton du Tessin, les autorités communa- les, et dans le canton du Valais, la police cantonale. -

MM 144/2016 Credito Di CHF. 300'000

MESSAGGIO MUNICIPALE NO. 144 _____________________________________ Magadino, 5 settembre 2016 Risoluzione municipale no. 1217 di competenza della Commissione opere pubbliche Richiesta di un credito di CHF 300'000.00, quale partecipazione ai costi d’investimento per la rete a banda larga, con tecnologia FTTC, costruita da Swisscom SA nel basso Gambarogno, a Piazzogna e a Indemini Egregio Signor Presidente, Gentil Signore, Egregi Signori Consiglieri comunali, La banda larga è un fattore cruciale di crescita economica e di occupazione poiché indispensabile per fornire servizi fondamentali in campo professionale, ricreativo e formativo. Nei compiti delle amministrazioni pubbliche, la messa a disposizione di collegamenti veloci è ormai diventata – al pari dell’usuale urbanizzazione del territorio – una delle condizioni a sostegno dello sviluppo socio economico. Di ciò già si parlava nel progetto aggregativo e negli ultimi anni il Municipio ha sondato e valutato ogni possibilità per accelerare l’implementazione della rete; purtroppo, sino ad oggi, nessun operatore del ramo aveva dimostrato un interesse particolare per investire nel nostro Comune. Il termine “banda larga” si riferisce in generale alla trasmissione e ricezione di dati, inviati e ricevuti sullo stesso cavo grazie all’uso di tecniche di trasmissione che sfruttano un’ampiezza di banda superiore ai precedenti sistemi di telecomunicazione, di solito eseguiti con doppini in rame. Più genericamente, si usa il termine “banda larga” come sinonimo di connessione alla rete internet più veloce di quella assicurata da un normale modem analogico. La disponibilità di una connessione a banda larga è in pratica indispensabile in qualunque sede di lavoro che richieda un’interazione via Internet. Nel nostro Comune la banda larga permetterebbe a proprietari di residenze secondarie di trasferire il proprio domicilio o di prolungare i soggiorni di permanenza, avendo garantita la possibilità di comunque seguire il proprio lavoro e/o interessi. -

Ticino on the Move

Tales from Switzerland's Sunny South Ticino on theMuch has changed move since 1882, when the first railway tunnel was cut through the Gotthard and the Ceneri line began operating. Mendrisio’sTHE LIGHT Processions OF TRADITION are a moving experience. CrystalsTREASURE in the AMIDST Bedretto THE Valley. ROCKS ChestnutsA PRICKLY are AMBASSADOR a fruit for all seasons. EasyRide: Travel with ultimate freedom. Just check in and go. New on SBB Mobile. Further information at sbb.ch/en/easyride. EDITORIAL 3 A lakeside view: Angelo Trotta at the Monte Bar, overlooking Lugano. WHAT'S NEW Dear reader, A unifying path. Sopraceneri and So oceneri: The stories you will read as you look through this magazine are scented with the air of Ticino. we o en hear playful things They include portraits of men and women who have strong ties with the local area in the about this north-south di- truest sense: a collective and cultural asset to be safeguarded and protected. Ticino boasts vide. From this year, Ticino a local rural alpine tradition that is kept alive thanks to the hard work of numerous young will be unified by the Via del people. Today, our mountain pastures, dairies, wineries and chestnut woods have also been Ceneri themed path. restored to life thanks to tourism. 200 years old but The stories of Lara, Carlo and Doris give off a scent of local produce: of hay, fresh not feeling it. milk, cheese and roast chestnuts, one of the great symbols of Ticino. This odour was also Vincenzo Vela was born dear to the writer Plinio Martini, the author of Il fondo del sacco, who used these words to 200 years ago. -

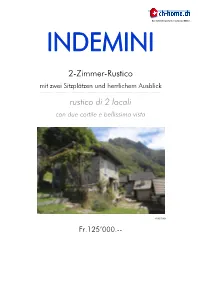

2-Zimmer-Rustico Rustico Di 2 Locali

Das Immobilienportal der Schweizer Makler. INDEMINI 2-Zimmer-Rustico mit zwei Sitzplätzen und herrlichem Ausblick …………………………………………………………...…………………………………………. rustico di 2 locali con due cortile e bellissima vista 4180/1809 Fr.125’000.-- Ubicazione Regione: Gambarogno Località: 6571 Indemini, zona Idacca Informazione sull’immobile Tipo dell’immobile: rustico di 2 locali Superficie terreno: ca. 42 m2 Superficie abitabile: ca. 35 m2 Cortile: 2 Piani: 2 Posteggi: gratuiti Locali: 2 Doccia/WC: 1 Riscaldamento: elettrico e camino Posizione: molto tranquilla e soleggiata Vista lago: si Scuole: in valle Possibilità d’acqusiti: in valle Mezzi pubblici: si Distanza prossima città: 25 km Distanza autostrada: 33 km Descrizione dell’immobile Questo rustico di 2 locali con due cortile si trova in posizione molto tranquilla e soleggiata sopra Indemini in zona Idacca a ca. 1200 m s/m. Il vecchio edificio è stato rinnovato e si trova in buono stato. Il rustico offre un ambiente accogliente in una zona con altri 20 a 30 rustici. Questo rustico comprende nel primo terra di un soggiorno con camino e cucina e un ripostiglio e nel primo piano di una camera con balcone e una doccia/WC. Accanto della casa si trovano due cortile/giardini. Da qui estende una bella vista sulle montagne e sulla valle e nel fondo si vede il Lago Maggiore. La proprietà è soleggiata tutto l’anno. Sul alpe Neggia si può anche sciare. Il rustico è facilmente raggiungibile in macchina tutto l’anno. Sotto la casa si trovano posteggi gratuiti. Il tragitto per Locarno e per l’autostrada A2 a Bellinzona-Sud dura ca. 45 minuti. -

62.329 S. Antonino - Cadenazzo - Magadino Debarcadero - Dirinella Stato: 6

ANNO D'ORARIO 2020 62.329 S. Antonino - Cadenazzo - Magadino Debarcadero - Dirinella Stato: 6. Novembre 2019 Lunedì–venerdì, salvo i giorni festivi generali, salvo 6.1., 19.3., 1.5., 11.6., 29.6., 8.12. nonché 2.1., 10.4. 101 103 107 109 111 113 115 117 S. Antonino, Paese 6 41 7 52 8 52 10 00 11 00 11 52 12 52 13 52 S. Antonino, 6 45 7 56 8 56 10 04 11 04 11 56 12 56 13 56 Centri Commerciali S. Antonino, 6 55 8 06 9 06 10 04 11 04 12 06 13 06 14 06 Centri Commerciali Cadenazzo, Stazione 6 58 8 09 9 09 10 07 11 07 12 09 13 09 14 09 Cadenazzo, Stazione 6 58 8 16 9 18 10 18 11 18 12 18 13 18 14 18 Contone, Posta 7 01 8 19 9 21 10 21 11 21 12 21 13 21 14 21 Quartino, Scuole 7 06 8 23 9 26 10 26 11 26 12 26 13 26 14 26 Quartino, Bivio 7 10 8 25 9 30 10 30 11 30 12 30 13 30 14 30 Magadino, Debarcadero 7 15 8 29 9 35 10 35 11 35 12 35 13 35 14 35 Magadino-Vira, Stazione 7 16 8 30 9 36 10 36 11 36 12 36 13 36 14 36 Vira (Gambarogno), Paese 7 17 8 31 9 37 10 37 11 37 12 37 13 37 14 37 S. Nazzaro, Paese 7 22 8 36 9 42 10 42 11 42 12 42 13 42 14 42 Gerra (Gambarogno), Paese 7 26 8 40 9 46 10 46 11 46 12 46 13 46 14 46 Ranzo, Paese 7 29 8 43 9 49 10 49 11 49 12 49 13 49 14 49 Dirinella, Confine 7 32 8 46 9 52 10 52 11 52 12 52 13 52 14 52 119 121 123 125 127 131 133 135 S. -

Informa... [email protected] L’Operatrice Sociale: Un Sostegno Prezioso

No.1 / 2016 Comune di Gambarogno informa... [email protected] L’operatrice sociale: www.gambarogno.ch un sostegno prezioso Con questa pubblicazione a carattere periodico, il Municipio vuole migliorare Può capitare a tutti, in un momento della propria l’informazione alla popolazione a complemento dei canali informativi già esistenti quali vita, di trovarsi in difficoltà: economica, di il sito internet, l’applicazione per smartphone, le notizie in pillole e i comunicati stampa. alloggio, familiare, di salute, con dipendenze… Il Bollettino rappresenterà l’occasione per approfondire temi che interessano tutta la cittadinanza e per conoscere meglio l’amministrazione Per chi si trova in questa situazione, da poco comunale. Vi auguro buona lettura. più di un anno, il Comune di Gambarogno ha a Tenersi in forma al Centro Tiziano Ponti, Sindaco disposizione un’operatrice sociale. Il suo compito sportivo e poi… un caffè è quello di sostenere la persona, di capire i suoi bisogni e di accompagnarla verso le possibili In bici da Contone a Magadino soluzioni, con lo scopo di migliorare il grado di in tutta sicurezza autonomia personale. Offre pure una consulenza sui diritti personali, sociali e finanziari. È garantita Tassa sul sacco la privacy di ogni utente. L’operatrice sociale collabora con tutti i servizi sul territorio comunale e cantonale. Lavora presso il Palazzo comunale Asilo nido comunale e mensa a Magadino, il lunedì e il martedì, tutto il giorno, per le scuole di Contone e Cadepezzo e il giovedì pomeriggio; riceve su appuntamento al numero 091/786.84.00. In caso di necessità si L’operatrice sociale: reca a domicilio o presso istituti di cura. -

923.250 Decreto Esecutivo Concernente Le Zone Di Protezione Pesca 2019-2024

923.250 Decreto esecutivo concernente le zone di protezione pesca 2019-2024 (del 24 ottobre 2018) IL CONSIGLIO DI STATO DELLA REPUBBLICA E CANTONE TICINO visti – la legge federale sulla pesca del 21 giugno 1991 (LFSP) e la relativa ordinanza del 24 novembre 1993 (OLFP), – la legge cantonale sulla pesca e sulla protezione dei pesci e dei gamberi indigeni del 26 giugno 1996 e il relativo regolamento di applicazione del 15 ottobre 1996, in particolare l’art. 19, – la Convenzione tra la Confederazione Svizzera e la Repubblica Italiana per la pesca nelle acque italo-svizzere del 1° aprile 1989, in particolare l’art. 6, decreta: Art. 1 Per il periodo dal 1° gennaio 2019 al 31 dicembre 2024, sono istituite le seguenti zone di protezione. a) Zone di protezione permanenti nei corsi d’acqua, dove la pesca è vietata: 1. Riale di Golino: dalla confluenza con il fiume Melezza alla prima cascata a monte della strada cantonale. 2. Torrente Brima ad Arcegno: dalla confluenza con il riale «Mulin di Cioss» all’entrata del paese di Arcegno, nonché tutta la tratta a valle dello sbarramento presso i mulini Simona a Losone. 3. Torrente Ribo a Vergeletto: dal ponte in località Custiell (pto. 891, poco a monte di Vergeletto) al ponte in ferro in località Zardin. 4. Fiume Bavona a Bignasco-Cavergno: dal ponte della cantonale a Bignasco fino alla passerella di Cavergno. 5. Roggia della piscicoltura di Sonogno: tutto il corso d’acqua fino alla confluenza con il fiume Verzasca. 6. Ronge di Alnasca a Brione Verzasca: dalla confluenza con il fiume Verzasca alle sorgenti. -

Piano Zone Biglietti E Abbonamenti 2021

Comunità tariffale Arcobaleno – Piano delle zone arcobaleno.ch – [email protected] per il passo per Geirett/Luzzone per Göschenen - Erstfeld del Lucomagno Predelp Carì per Thusis - Coira per il passo S. Gottardo Altanca Campo (Blenio) S. Bernardino (Paese) Lurengo Osco Campello Quinto Ghirone 251 Airolo Mairengo 243 Pian S. Giacomo Bedretto Fontana Varenzo 241 Olivone Tortengo Calpiogna Mesocco per il passo All’Acqua Piotta Ambrì Tengia 25 della Novena Aquila 245 244 Fiesso Rossura Ponto Soazza Nante Rodi Polmengo Valentino 24 Dangio per Arth-Goldau - Zurigo/Lucerna Fusio Prato Faido 250 (Leventina) 242 Castro 331 33 Piano Chiggiogna Torre Cabbiolo Mogno 240 Augio Rossa S. Carlo di Peccia Dalpe Prugiasco Lostallo 332 Peccia Lottigna Lavorgo 222 Sorte Menzonio Broglio Sornico Sonogno Calonico 23 S. Domenica Prato Leontica Roseto 330 Cama Brontallo 230 Acquarossa 212 Frasco Corzoneso Cauco Foroglio Nivo Giornico Verdabbio Mondada Cavergno 326 Dongio 231 S. Maria Leggia Bignasco Bosco Gurin Gerra (Verz.) Chironico Ludiano Motto (Blenio) 221 322 Sobrio Selma 32 Semione Malvaglia 22 Grono Collinasca Someo Bodio Arvigo Cevio Brione (Verz.) Buseno Personico Pollegio Loderio Cerentino Linescio Riveo Giumaglio Roveredo (GR) Coglio Campo (V.Mag.) 325 Osogna 213 320 Biasca 21 Lodano Lavertezzo 220 Cresciano S. Vittore Cimalmotto 324 Maggia Iragna Moghegno Lodrino Claro 210 Lumino Vergeletto Gresso Aurigeno Gordevio Corippo Vogorno Berzona (Verzasca) Prosito 312 Preonzo 323 31 311 Castione Comologno Russo Berzona Cresmino Avegno Mergoscia Contra Gordemo Gnosca Ponte Locarno Gorduno Spruga Crana Mosogno Loco Brolla Orselina 20 Arbedo Verscio Monti Medoscio Carasso S. Martino Brione Bellinzona Intragna Tegna Gerra Camedo Borgnone Verdasio Minusio s. -

Canton Ticino and the Italian Swiss Immigration to California

Swiss American Historical Society Review Volume 56 Number 1 Article 7 2020 Canton Ticino And The Italian Swiss Immigration To California Tony Quinn Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review Part of the European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Quinn, Tony (2020) "Canton Ticino And The Italian Swiss Immigration To California," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 56 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol56/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swiss American Historical Society Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Quinn: Canton Ticino And The Italian Swiss Immigration To California Canton Ticino and the Italian Swiss Immigration to California by Tony Quinn “The southernmost of Switzerland’s twenty-six cantons, the Ticino, may speak Italian, sing Italian, eat Italian, drink Italian and rival any Italian region in scenic beauty—but it isn’t Italy,” so writes author Paul Hofmann1 describing the one Swiss canton where Italian is the required language and the cultural tie is to Italy to the south, not to the rest of Switzerland to the north. Unlike the German and French speaking parts of Switzerland with an identity distinct from Germany and France, Italian Switzerland, which accounts for only five percent of the country, clings strongly to its Italian heritage. But at the same time, the Ticinese2 are fully Swiss, very proud of being part of Switzerland, and with an air of disapproval of Italy’s ever present government crises and its tie to the European Union and the Euro zone, neither of which Ticino has the slightest interest in joining. -

Il Sentiero Educativo Vairano – Contone Il Sentiero Educativo L

L’avvento della ferrovia, La Chiesa di San Carlo Borromeo Il bacino lacustre la decadenza del porto 10 e la villa Ghisler 11 del Lago Maggiore 12 e i mutamenti socio-economici La foce del Ticino e della Verzasca Il 2 ottobre 1844 Moraglia presentò tre progetti; uno fu scelto e i lavori iniziarono. Tutti dovevano in un qualche modo partecipare alla costru- zione. Allora il Municipio decise di far trasportare il materiale necessario alla costruzione a tutti gli abitanti del nuovo Comune. Nei giorni festivi 1846 le donne dovevano trasportare la sabbia dal lago al cantiere, mentre gli uomini venivano impiegati come manovali o muratori. Chi non parteci- pava veniva multato! foce della Verzasca foce del Ticino Nel 1846 la Chiesa fu terminata ma senza il campanile che venne 1872 aggiunto in un secondo tempo. La Chiesa fu dedicata a San Carlo 1 1 1 Borromeo, patrono della parrocchia, Arcivescovo della diocesi di Milano Con l’avvento della costruzione della linea ferroviaria del S.Gottardo Nel 1800 Magadino era il Porto d’eccellenza del lago Maggiore, il suo nel 1500, il quale avrebbe compiuto un miracolo in una stalla in fiamme L’inizio della formazione del Verbano è coincisa con il ritiro del ghiacciaio (1872 – 1882), inizialmente progettata attraverso il Gambarogno, sviluppo fece fiorire sul lungolago alberghi rinomati e depositi, destinati nella frazione di Magadino superiore. Facendo il segno della croce in del Ticino, iniziata circa 20’500 anni fa. La conca lasciata libera dai l’importanza di Magadino diminuì. Quando fu aperta la linea Bellinzona- al transito di merci e persone. -

Nei Dialetti Del Canton Ticino E Territorii Limitrofi : (Con 3 Carte)

Dei continuatori di *lcrta (* -u) nei dialetti del Canton Ticino e territorii limitrofi : (con 3 carte) Autor(en): Merlo, C. Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Bollettino dell'opera del Vocabolario della Svizzera italiana Band (Jahr): 5 (1929) Heft 5 PDF erstellt am: 01.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-178761 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch 4 BOLLETT. OPERA DEL VOC. DELLA SVIZZERA ITALIANA (N. 5) *des-, donde *ds- e quindi *ts-; il *ts si è infine invertito in st-. L' il è sorto nelle rizatone per la vicinanza del ú '. t C. Salvioni.