Costing Models for Language Maintenance, Revitalization, and Reclamation in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blackfoot Language for the Morning Indigenous (Blackfoot) Language

LESSON PLAN Date:_____________________________ Blackfoot Language for the Morning Indigenous (Blackfoot) Language ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Origin Please read this Acknowledgement before the start of this lesson to respect the knowledge that is being shared and the Land of the People where the knowledge Kainai First Nation originates.: Alberta The original signatories for The Articles of Treaty 7 include the Blackfoot, Blood, Peigan, Sarcee, and Stoney nations as well as Her Majesty the Queen of England on Learning Level / Grade behalf of Canada. Treaty 7 was signed on September 22, 1877. This document describes the expansive lands exchanged for benefits promised into perpetuity to the descendants of the signatories which include health care, schools and reserved land. Beginner The Treaty is a living document, all people living in Treaty 7 territory are treaty members bound with mutual responsibilities to support peaceful co-existence. Language LEARNING OUTCOMES Upon successful completion of this lesson plan, students will be able to: 130 mins 1. Share factual information by describing series or sequences of events or actions (in this case, his/her morning routine). [A-1, A-1.1] 2. Use the language creatively, for imaginative purposes and personal enjoyment Cross-Curricular and for creative/aesthetic purposes by creating a picture story with captions. (Related) Subjects [A-6, A-6.2] 3. Attend to the form of the language with simple sentences using I, you, Indigenous Ways of Knowing he/she, and subjects and action words in declarative statements. [LC-1 [1S, 2S, & Being 3S, VAI]] 4. Form positive relationships with others; e.g., peers, family, and Elders. -

Toward the Reconstruction of Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan. Part 3: the Algonquian-Wakashan 110-Item Wordlist

Sergei L. Nikolaev Institute of Slavic studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow/Novosibirsk); [email protected] Toward the reconstruction of Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan. Part 3: The Algonquian-Wakashan 110-item wordlist In the third part of my complex study of the historical relations between several language families of North America and the Nivkh language in the Far East, I present an annotated demonstration of the comparative data that was used in the lexicostatistical calculations to determine the branching and approximate glottochronological dating of Proto-Algonquian- Wakashan and its offspring; because of volume considerations, this data could not be in- cluded in the previous two parts of the present work and has to be presented autonomously. Additionally, several new Proto-Algonquian-Wakashan and Proto-Nivkh-Algonquian roots have been set up in this part of study. Lexicostatistical calculations have been conducted for the following languages: the reconstructed Proto-North Wakashan (approximately dated to ca. 800 AD) and modern or historically attested variants of Nootka (Nuuchahnulth), Amur Nivkh, Sakhalin Nivkh, Western Abenaki, Miami-Peoria, Fort Severn Cree, Wiyot, and Yurok. Keywords: Algonquian-Wakashan languages, Nivkh-Algonquian languages, Algic languages, Wakashan languages, Chimakuan-Wakashan languages, Nivkh language, historical phonol- ogy, comparative dictionary, lexicostatistics. The classification and preliminary glottochronological dating of Algonquian-Wakashan currently remain the same as presented in Nikolaev 2015a, Fig. 1 1. That scheme was generated based on the lexicostatistical analysis of 110-item basic word lists2 for one reconstructed (Proto-Northern Wakashan, ca. 800 A.D.) and several modern Algonquian-Wakashan lan- guages, performed with the aid of StarLing software 3. -

Subordinate Clauses in Squamish 1 Subordinate Clauses in S W Wu7mesh

Subordinate Clauses in Squamish 1 Subordinate Clauses in Sk w xx wu7mesh: Their Form and Function Peter Jacobs University of Victoria ABSTRACT: This paper examines three subordinate clause types in Sk w xx wu7mesh: nominalized clauses, conjunctive clauses and /u/ clauses. These three clause types overlap in their syntactic functions. The first two clause types function as complement clauses. All three clause types function as adverbial clauses. I propose that the distribution of these clause types is due to the degree of certainty of the truth of the subordinate clause proposition, whether from the speaker’s perspective or that of the main clause subject. KEYWORDS: Skwxwu7mesh, Salish, subjunctives, conditionals, subordination 1. Introduction Sk w xx wu7mesh (a.k.a. Squamish) is a Coast Salish language traditionally spoken in an area that extends from Burrard Inlet in Vancouver, along both sides of Howe Sound, and through the Squamish River Valley and the Cheakamus River Valley in southwestern British Columbia.1 This paper is an examination of three subordinate clauses types in Sk w xx wu7mesh: conjunctive clauses, nominalized clauses and /u/ clauses.2 Conjunctive clauses and nominalized clauses function as sentential complements and as adverbial clauses. /u/ clauses only function as adverbial clauses. This paper examines the semantic and functional-pragmatic factors that control the use of these clause types. I do not provide an exhaustive examination of subordination in Sk w xx wu7mesh. That is, I do not consider relative clauses nor clause chaining (a special type of nominalized clause). While such an examination is necessary to understand the full range of subordination strategies in Sk w xx wu7mesh, it is beyond the scope of this paper. -

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) Motion of K stars in line of sight Ka-đai language USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) Radial velocity of K stars USE Kadai languages K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) — Orbits Ka’do Herdé language USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) UF Galactic orbits of K stars USE Herdé language K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) K stars—Galactic orbits Ka’do Pévé language UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) BT Orbits USE Pévé language K9 (Fictitious character) — Radial velocity Ka Dwo (Asian people) K 37 (Military aircraft) USE K stars—Motion in line of sight USE Kadu (Asian people) USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) — Spectra Ka-Ga-Nga script (May Subd Geog) K 98 k (Rifle) K Street (Sacramento, Calif.) UF Script, Ka-Ga-Nga USE Mauser K98k rifle This heading is not valid for use as a geographic BT Inscriptions, Malayan K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 subdivision. Ka-houk (Wash.) USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 BT Streets—California USE Ozette Lake (Wash.) K.A. Lind Honorary Award K-T boundary Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary UF Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) K.A. Linds hederspris K-T Extinction Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction BT National parks and reserves—Hawaii K-ABC (Intelligence test) K-T Mass Extinction Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-B Bridge (Palau) K-TEA (Achievement test) Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-BIT (Intelligence test) K-theory Ka-ju-ken-bo USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test [QA612.33] USE Kajukenbo K. -

SFU Library Thesis Template

Building blocks for developing a Hən̓ q̓ əmín̓ əm̓ Language Nest Program for the Katzie Early Years Centre by Cheyenne Cunningham B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2017 Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Cheyenne Cunningham 2019 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2019 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Cheyenne Cunningham Degree: Master of Arts Title: Building blocks for developing a Hən̓ q̓ əmín̓ əm̓ Language Nest Program for the Katzie Early Years Centre Examining Committee: Chair: Nancy Hedberg Professor Marianne Ignace Senior Supervisor Professor Susan Russell Supervisor Adjunct Professor Date Defended/Approved: April 17, 2019 ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract As a First Nations woman and community member of the q̓ ícəy̓ (Katzie) First Nation, I have always had an interest in the language of my ancestors – Hən̓ q̓ əmín̓ əm̓ , the Downriver dialect of the Halkomelem language, a Coast Salish language that has no first language speakers left. My interest in the language stems from my childhood, as I was lucky enough to have the opportunity to participate in classes that exposed me to the language. The purpose of this project is to not only enhance my own knowledge but to also create framework for what will hopefully be used for a language nest program for the Katzie Early Years Centre. The idea is to provide a safe environment for the children to interact and engage in the language through meaningful activities. -

Aborlit Algonquian Eastern Canada 20080411

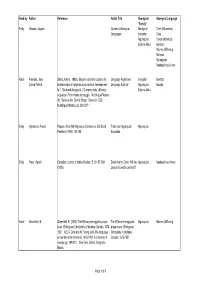

Read by Author Reference Article Title Aboriginal Aboriginal Language "Family" Emily Maurais, Jaques Quebec's Aboriginal Aboriginal Cree (Atikamekw) Languages Iroquoian Cree Algonquian Huron (Wyandot) Eskimo-Aleut Inuktitut Micmac (Mi’kmaq) Mohawk Montagnais Naskapi-Innu-Aimun Karlie Freeland, Jane Stairs, Arlene. 1988a. Beyond cultural inclusion: An Language Rights and Iroquoian Inuktitut Donna Patrick Inuit example of indigenous educational development. Language Survival Algonquian Inupiaq In T. Skutnabb-Kangas & J. Cummins (eds.) Minority Eskimo-Aleut education: From shame to struggle. Multilingual Matters 40. Series editor Derrick Sharp. Clevedon, G.B.: Multilingual Matters, pp. 308-327. Emily Hjartarson, Freida Papers of the 26th Algonquin Conference. Ed. David Traditional Algonquian Algonquian Pentland (1995): 151-168 Education Emily Press, Harold Canadian Journal of Native Studies 15 (2) 187-209 Davis Inlet in Crisis: Will the Algonquian Naskapi-Innu-Aimun (1995) Lessons Ever be Learned? Karlie Greenfield, B. Greenfield, B. (2000) The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic prayer The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic Algonquian Micmac (Mi’kmaq) book: Writing and Christianity in Maritime Canada, 1675- prayer book: Writing and 1921. In E.G. Gray and N. Fiering (eds) The language Christianity in Maritime encounter in the Americas, 1492-1800: A collection of Canada, 1675-1921 essays (pp. 189-211). New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books. Page 1 of 9 Majority Relevant Area Specific Area Age Time Period Discipline of Research Type of Language Research French Canada Quebec -

Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous Languages of the Americas

Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous Languages of the Americas edited by Andrea L. Berez, Jean Mulder, and Daisy Rosenblum Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 2 Published as a sPecial Publication of language documentation & conservation language documentation & conservation Department of Linguistics, UHM Moore Hall 569 1890 East-West Road Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822 USA http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc university of hawai‘i Press 2840 Kolowalu Street Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822-1888 USA © All texts and images are copyright to the respective authors. 2010 All chapters are licensed under Creative Commons Licenses Cover design by Cameron Chrichton Cover photograph of salmon drying racks near Lime Village, Alaska, by Andrea L. Berez Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data ISBN 978-0-8248-3530-9 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4463 Contents Foreword iii Marianne Mithun Contributors v Acknowledgments viii 1. Introduction: The Boasian tradition and contemporary practice 1 in linguistic fieldwork in the Americas Daisy Rosenblum and Andrea L. Berez 2. Sociopragmatic influences on the development and use of the 9 discourse marker vet in Ixil Maya Jule Gómez de García, Melissa Axelrod, and María Luz García 3. Classifying clitics in Sm’algyax: 33 Approaching theory from the field Jean Mulder and Holly Sellers 4. Noun class and number in Kiowa-Tanoan: Comparative-historical 57 research and respecting speakers’ rights in fieldwork Logan Sutton 5. The story of *o in the Cariban family 91 Spike Gildea, B.J. Hoff, and Sérgio Meira 6. Multiple functions, multiple techniques: 125 The role of methodology in a study of Zapotec determiners Donna Fenton 7. -

Lillooet Between Sechelt and Shuswap Jan P. Van Eijk First

Lillooet between Sechelt and Shuswap Jan P. van Eijk First Nations University of Canada Although most details of the grammatical and lexical structure of Lillooet put this language firmly within the Interior branch of the Salish language family, Lillooet also shares some features with the Coast or Central branch. In this paper we describe some of the similarities between Lillooet and one of its closest Interior relatives, viz., Shuswap, and we also note some similarities be tween Lillooet and Sechelt, one of Lillooet' s western neighbours but belonging to the Coast branch. Particular attention is paid to some obvious loans between Lillooet and Sechelt. 1 Introduction Lillooet belongs with Shuswap to the Interior branch of the Salish language family, while Sechelt belongs to the Coast or Central branch. In what follows we describe the similarities and differences between Lillooet and both Shuswap and Sechelt, under the following headings: Phonology (section 2), Morphology (3), Lexicon (4), and Lillooet-Sechelt borrowings (5). Conclusions are given in 6. I omit a comparison between the syntactic patterns of these three languages, since my information on Sechelt syntax is limited to a brief text (Timmers 1974), and Beaumont 1985 is currently unavailable to me. Although borrowings between Lillooet and Shuswap have obviously taken place, many of these will be impossible to trace due to the close over-all resemblance between these two languages. Shuswap data are mainly drawn from the western dialects, as described in Kuipers 1974 and 1975. (For a description of the eastern dialects I refer to Kuipers 1989.) Lillooet data are from Van Eijk 1997, while Sechelt data are from Timmers 1973, 1974, 1977. -

Sustaining Indigenous Languages Looking Back, Looking Forward Inge Genee and Conor Snoek

Sustaining Indigenous Languages Looking Back, Looking Forward Inge Genee and Conor Snoek In the past decade or so, the endangerment of many of the world’s Indigenous and other minority languages has begun to percolate into the public consciousness, becoming part of the wider debate about cultural, environmental, and economic sustainability. The United Nations declaration of 2019 as the International Year of Indigenous Languages (en.iyil2019.org) can be considered emblematic of the rise in global awareness of the threat of language extinction. Popular press articles about language endangerment are becoming more common, and local papers often comment on initiatives to revitalize or maintain Indigenous languages of a specific group or territory. In addition, social media groups promote and support individual language communities and provide a means of connecting speakers living outside their communities of origin. It is becoming clearer all the time that language maintenance has many benefits in addition to the preservation of unique ways of seeing the world, including mental and physical health benefits (Biddle and Swee 2012; Hallett et al. 2007; Whalen et al. 2016), community benefits (Romero-Little et al. 2011) and educational benefits (Huffmann 2018; Luning and Yamaguchi 2010; Reyhner 2017). Indigenous language communities and linguists working in Indigenous language documentation and related fields have been aware of the threat to In- digenous languages for several decades. Passionate writings calling the linguistic community to action emerged as early as the 1990s (Crawford 1998; Grenoble and Whaley 1998; Hinton 1997; Krauss 1992), but, like the climate scientists who long warned of a looming crisis, linguists and language activists have struggled to be heard. -

Reduplicated Numerals in Salish. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 11P.; for Complete Volume, See FL 025 251

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 419 409 FL 025 252 AUTHOR Anderson, Gregory D. S. TITLE Reduplicated Numerals in Salish. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 11p.; For complete volume, see FL 025 251. PUB TYPE Journal Articles (080) Reports Research (143) JOURNAL CIT Kansas Working Papers in Linguistics; v22 n2 p1-10 1997 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indian Languages; Contrastive Linguistics; Language Patterns; *Language Research; Language Variation; *Linguistic Theory; Number Systems; *Salish; *Structural Analysis (Linguistics); Uncommonly Taught Languages ABSTRACT A salient characteristic of the morpho-lexical systems of the Salish languages is the widespread use of reduplication in both derivational and inflectional functions. Salish reduplication signals such typologically common categories as "distributive/plural," "repetitive/continuative," and "diminutive," the cross-linguistically marked but typically Salish notion of "out-of-control" or more restricted categories in particular Salish languages. In addition to these functions, reduplication also plays a role in numeral systems of the Salish languages. The basic forms of several numerals appear to be reduplicated throughout the Salish family. In addition, correspondences among the various Interior Salish languages suggest the association of certain reduplicative patterns with particular "counting forms" referring to specific nominal categories. While developments in the other Salish language are frequently more idiosyncratic and complex, comparative evidence suggests that the -

Tahltan Verb Classifiers and How to Use Them

Tahltan Verb Classifiers and How to Use Them by Louise Framst Certificate in First Nations Language Proficiency (Tahltan), Simon Fraser University, 2017 B.Ed., University of British Columbia,1981 Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Louise Framst 2019 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2019 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Louise Framst Degree: Master of Arts Title: Tahltan Verb Classifiers and How to Use Them Examining Committee: Chair: Nancy Hedberg Professor Marianne Ignace Senior Supervisor Professor John Alderete Supervisor Professor Date Defended/Approved: April 16, 2019 ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract One frustration as a learner of my heritage language, Tāłtān, is the lack of resources. I created four booklets on what we learned as Tahltan Verb Classifiers; the linguistic term is classificatory verbs. Each booklet contains a different aspect of this feature; includes lessons in how to use it. A literature review revealed it had never been thoroughly researched. Therefore, information came from: language classes, instructors, recordings, and fluent speakers. My interviews: five individuals and one group session of seven. Most fluent speakers were unavailable; that is the problem when your ‘dictionaries’ have legs. The ‘big’ lesson I learned is that it is imperative we focus on collecting vocabulary before the words fade away from non-use. iv Keywords: classificatory verbs, Tahltan verb classifiers, Tāłtān, Tahltan language, immersion, First Nations learning, stress-response v Dedication Dedicated to the Elders and Fluent Speakers, Our Tāłtān language mentors. -

Article Title

Dennis L. Malone and Isara Choosri Stabilizing Indigenous Languages 1 Symposium Report Stabilizing Indigenous Languages Dennis L. Malone and Isara Choosri* A note from Pat Kelley, SIL International Literacy Coordinator Few of our field practitioners are strategically located for attending some of the conferences around the world that may be related to the work we do in literacy. Also, in many cases, especially if no paper is being presented, there may be limited funds available for transportation. Yet there is much to be learned from such conferences: for example, vocabulary and new terminology, current trends, what’s “out there” in the prominent theory and practice of related fields applicable to our work, current research, issues defined by the “voices” for literacy, etc. For that reason, when our SIL literacy personnel and national colleagues do attend or present at a conference, on occasion we’ll include a “Conference Report” … so that our field personnel may glean information from them. When possible, contact details will be provided in order to request additional information. These reports will reflect the growing trend in the Literacy domain for copresenting and coauthoring, which hopefully will continue as we determine to see capacity building in this area among our national colleagues. Dennis Malone (SIL International in Bangkok, Thailand), and Isara Choosri (Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development at Mahidol University at Salaya, Thailand) coauthor this report of the Ninth Annual Symposium on Stabilizing Indigenous • Dennis Malone ([email protected]) is an International Literacy Consultant, serving with his wife Susan in the Asia Area. He is involved in minority language education projects in the Asia Area and also serves as a guest lecturer at the ILCRD.