Unforeseen Directions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

* . Leumtttg Ll^Raui

. ..* . The Weather Partiy cloudy, ooolor tontgliL lEum tttg ll^ ra U i Low aiiioiit 40. Tom om w most ly cloudy, brooiy, cool. U g h in tlM low DOS. Manch«$ter— A City of VUiage Charm MANCHESTER, OONN^ MONDAY, OCTOBER 28, 1988 (OImmUM AdvertUluy «■ >t) PRICE TEN CENTS South Viet State Poll Says LBJ Joins HHH Nixon and Ribicoff Troops Hit HARTFORD, Conn. (AP)— Czech Students March A poll conducted for the Hartford Times showed to In Blasting Nixon day Connecticut voters favor Veteran Unit ing Republican presidential By THE ASSORTED PBE88 ourlty gap asid ohaigea about candidate Richard M. Nixon 8AIGK>N (A P ) — South V iet- President Johnson has ac our attempts to win peace in the over Democrat Hubert H. iwnMM Intuitrymon •maahed cused Richard M. Nixon of mak w o rid ." Humphrey, but Democratic Into troops from a veteran ing "ugly and urdalr ohaiges" Humphrey issued a statement Incumbent Abraham Ribicoff North Vletnameae regiment that on security and peace efforts On Presidential Castle after Nixon’s television appear over OOP candidate Edwin spearheaded two offensives on and Hubert II. Humphrey ance, charging him with “using H. May in the U.S. Senate PRAGUE (AP) — Thousands Saigon this year, government charges Nixon with spreading a tactic wMch he has used In so ra ce. m dK ary h eadquarters an* an imfounded rumor that the many campaigns.’ ' The copyrighted poll said of CaechosiovakB marched tai nounoed today. Democrats are playing politics Nixon was favored by 44 per Prague today ta patriotic dem- "The tactic; spread an un A government spokesman with peace. -

Adapting to Institutional Change in New Zealand Politics

21. Taming Leadership? Adapting to Institutional Change in New Zealand Politics Raymond Miller Introduction Studies of political leadership typically place great stress on the importance of individual character. The personal qualities looked for in a New Zealand or Australian leader include strong and decisive action, empathy and an ability to both reflect the country's egalitarian traditions and contribute to a growing sense of nationhood. The impetus to transform leaders from extraordinary people into ordinary citizens has its roots in the populist belief that leaders should be accessible and reflect the values and lifestyle of the average voter. This fascination with individual character helps account for the sizeable biographical literature on past and present leaders, especially prime ministers. Typically, such studies pay close attention to the impact of upbringing, personality and performance on leadership success or failure. Despite similarities between New Zealand and Australia in the personal qualities required of a successful leader, leadership in the two countries is a product of very different constitutional and institutional traditions. While the overall trend has been in the direction of a strengthening of prime ministerial leadership, Australia's federal structure of government allows for a diffusion of leadership across multiple sources of influence and power, including a network of state legislatures and executives. New Zealand, in contrast, lacks a written constitution, an upper house, or the devolution of power to state or local government. As a result, successive New Zealand prime ministers and their cabinets have been able to exercise singular power. This chapter will consider the impact of recent institutional change on the nature of political leadership in New Zealand, focusing on the extent to which leadership practices have been modified or tamed by three developments: the transition from a two-party to a multi-party parliament, the advent of coalition government, and the emergence of a multi-party cartel. -

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1955-1958

THE COMMONWEALTH TRANS-ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1955-1958 HOW THE CROSSING OF ANTARCTICA MOVED NEW ZEALAND TO RECOGNISE ITS ANTARCTIC HERITAGE AND TAKE AN EQUAL PLACE AMONG ANTARCTIC NATIONS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree PhD - Doctor of Philosophy (Antarctic Studies – History) University of Canterbury Gateway Antarctica Stephen Walter Hicks 2015 Statement of Authority & Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Elements of material covered in Chapter 4 and 5 have been published in: Electronic version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume00,(0), pp.1-12, (2011), Cambridge University Press, 2011. Print version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume 49, Issue 1, pp. 50-61, Cambridge University Press, 2013 Signature of Candidate ________________________________ Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................. -

REFERENCE LIST: 10 (4) Legat, Nicola

REFERENCE LIST: 10 (4) Legat, Nicola. "South - the Endurance of the Old, the Shock of the New." Auckland Metro 5, no. 52 (1985): 60-75. Roger, W. "Six Months in Another Town." Auckland Metro 40 (1984): 155-70. ———. "West - in Struggle Country, Battlers Still Triumph." Auckland Metro 5, no. 52 (1985): 88-99. Young, C. "Newmarket." Auckland Metro 38 (1984): 118-27. 1 General works (21) "Auckland in the 80s." Metro 100 (1989): 106-211. "City of the Commonwealth: Auckland." New Commonwealth 46 (1968): 117-19. "In Suburbia: Objectively Speaking - and Subjectively - the Best Suburbs in Auckland - the Verdict." Metro 81 (1988): 60-75. "Joshua Thorp's Impressions of the Town of Auckland in 1857." Journal of the Auckland Historical Society 35 (1979): 1-8. "Photogeography: The Growth of a City: Auckland 1840-1950." New Zealand Geographer 6, no. 2 (1950): 190-97. "What’s Really Going On." Metro 79 (1988): 61-95. Armstrong, Richard Warwick. "Auckland in 1896: An Urban Geography." M.A. thesis (Geography), Auckland University College, 1958. Elphick, J. "Culture in a Colonial Setting: Auckland in the Early 1870s." New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies 10 (1974): 1-14. Elphick, Judith Mary. "Auckland, 1870-74: A Social Portrait." M.A. thesis (History), University of Auckland, 1974. Fowlds, George M. "Historical Oddments." Journal of the Auckland Historical Society 4 (1964): 35. Halstead, E.H. "Greater Auckland." M.A. thesis (Geography), Auckland University College, 1934. Le Roy, A.E. "A Little Boy's Memory of Auckland, 1895 to Early 1900." Auckland-Waikato Historical Journal 51 (1987): 1-6. Morton, Harry. -

Route N10 - City to Otara Via Manukau Rd, Onehunga, Mangere and Papatoetoe

ROUTE N10 - CITY TO OTARA VIA MANUKAU RD, ONEHUNGA, MANGERE AND PAPATOETOE Britomart t S Mission F t an t r t sh e S e S Bay St Marys aw Qua College lb n A y S e t A n Vector Okahu Bay St Heliers Vi e z ct t a o u T r S c Arena a Kelly ia Kohimarama Bay s m A S Q Tarltons W t e ak T v a e c i m ll e a Dr Beach es n ki le i D y S Albert r r t P M Park R Mission Bay i d a Auckland t Dr St Heliers d y D S aki r Tama ki o University y m e e Ta l r l l R a n Parnell l r a d D AUT t S t t S S s Myers n d P Ngap e n a ip Park e r i o Auckland Kohimarama n R u m e y d Domain d Q l hape R S R l ga d an R Kar n to d f a N10 r Auckland Hobson Bay G Hospital Orakei P Rid a d de rk Auckland ll R R R d d Museum l d l Kepa Rd R Glendowie e Orakei y College Grafton rn Selwyn a K a B 16 hyb P College rs Glendowie Eden er ie Pass d l Rd Grafton e R d e Terrace r R H Sho t i S d Baradene e R k h K College a Meadowbank rt hyb r No er P Newmarket O Orakei ew ass R Sacred N d We Heart Mt Eden Basin s t Newmarket T College y a Auckland a m w a ki Rd Grammar d a d Mercy o Meadowbank R r s Hospital B St Johns n Theological h o St John College J s R t R d S em Remuera Va u Glen ll d e ey G ra R R d r R Innes e d d St Johns u a Tamaki R a t 1 i College k S o e e u V u k a v lle n th A a ra y R R d s O ra M d e Rd e u Glen Innes i em l R l i Remuera G Pt England Mt Eden UOA Mt St John L College of a Auckland Education d t University s i e d Ak Normal Int Ea Tamaki s R Kohia School e Epsom M Campus S an n L o e i u n l t e e d h re Ascot Ba E e s Way l St Cuthberts -

Māori and Aboriginal Women in the Public Eye

MĀORI AND ABORIGINAL WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC EYE REPRESENTING DIFFERENCE, 1950–2000 MĀORI AND ABORIGINAL WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC EYE REPRESENTING DIFFERENCE, 1950–2000 KAREN FOX THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Fox, Karen. Title: Māori and Aboriginal women in the public eye : representing difference, 1950-2000 / Karen Fox. ISBN: 9781921862618 (pbk.) 9781921862625 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Women, Māori--New Zealand--History. Women, Aboriginal Australian--Australia--History. Women, Māori--New Zealand--Social conditions. Women, Aboriginal Australian--Australia--Social conditions. Indigenous women--New Zealand--Public opinion. Indigenous women--Australia--Public opinion. Women in popular culture--New Zealand. Women in popular culture--Australia. Indigenous peoples in popular culture--New Zealand. Indigenous peoples in popular culture--Australia. Dewey Number: 305.4880099442 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover image: ‘Maori guide Rangi at Whakarewarewa, New Zealand, 1935’, PIC/8725/635 LOC Album 1056/D. National Library of Australia, Canberra. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Abbreviations . ix Illustrations . xi Glossary of Māori Words . xiii Note on Usage . xv Introduction . 1 Chapter One . -

Ōtara-Papatoetoe Area Plan December 2014 TABLE of CONTENTS TATAI KORERO

BC3685 THE OTARA-PAPATOETOE REA PLA MAHERE A ROHE O OTARA-PAPATOETOE DECEMBER 2014 HE MIHI Tēnā kia hoea e au taku waka mā ngā tai mihi o ata e uru ake ai au mā te awa o Tāmaki ki te ūnga o Tainui waka i Ōtāhuhu. I reira ka toia aku mihi ki te uru ki te Pūkaki-Tapu-a-Poutūkeka, i reira ko te Pā i Māngere. E hoe aku mihi mā te Mānukanuka a Hoturoa ki te kūrae o te Kūiti o Āwhitu. I kona ka rere taku haere mā te ākau ki te puaha o Waikato, te awa tukukiri o ngā tūpuna, Waikato Taniwharau, he piko he taniwha. Ka hīkoi anō aku mihi mā te taha whakararo mā Maioro ki Waiuku ki Mātukureira kei kona ko ngā Pā o Tahuna me Reretewhioi. Ka aro whakarunga au kia tau atu ki Pukekohe. Ka tahuri te haere a taku reo ki te ao o te tonga e whāriki atu rā mā runga i ngā hiwi, kia taka atu au ki Te Paina, ki te Pou o Mangatāwhiri. Mātika tonu aku mihi ki a koe Kaiaua te whākana atu rā ō whatu mā Tīkapa Moana ki te maunga tapu o Moehau. Ka kauhoetia e aku kōrero te moana ki Maraetai kia hoki ake au ki uta ki Ōhuiarangi, heteri mō Pakuranga. I reira ka hoki whakaroto ake anō au i te awa o Tāmaki ma te taha whakarunga ki te Puke o Taramainuku, kei konā ko Ōtara. Kātahi au ka toro atu ki te Manurewa a Tamapohore, kia whakatau aku mihi mutunga ki runga o Pukekiwiriki kei raro ko Papakura ki konā au ka whakatau. -

Cluster 10 Schools List

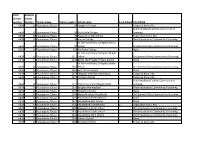

FIRST EDUMIS Cluster Cluster number Number Cluster Name School number School name Lead School COL NAME 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 58 Tangaroa College Tangaroa Kahui Ako South Auckland Catholic Community of 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 94 De La Salle College Learning 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 95 Papatoetoe High School Papatoetoe Kahui Ako 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 96 Aorere College West Papatoetoe Community of Learning Sir Edmund Hillary Collegiate Senior 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 97 School Sir Edmund Hillary Community of Learning 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 631 Kia Aroha College None Sir Edmund Hillary Collegiate Middle 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1217 School Sir Edmund Hillary Community of Learning 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1218 Bairds Mainfreight Primary School None Sir Edmund Hillary Collegiate Junior 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1251 School Sir Edmund Hillary Community of Learning 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1264 East Tamaki School None 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1274 Ferguson Intermediate (Otara) Tangaroa Kahui Ako 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1277 Flat Bush School Tangaroa Kahui Ako South Auckland Catholic Community of 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1315 Holy Cross School (Papatoetoe) Learning 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1329 Kedgley Intermediate West Papatoetoe Community of Learning 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1333 Kingsford School None 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1369 Mayfield School (Auckland) Sir Edmund Hillary Community of Learning 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1426 Papatoetoe Central School None 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1427 Papatoetoe East School None 6439 -

Maintenance of State Housing Offi Ce of the Auditor-General PO Box 3928, Wellington 6140

Performance audit report Housing New Zealand Corporation: Maintenance of state housing Offi ce of the Auditor-General PO Box 3928, Wellington 6140 Telephone: (04) 917 1500 Facsimile: (04) 917 1549 Email: [email protected] www.oag.govt.nz Housing New Zealand Corporation: Maintenance of state housing This is an independent assurance report about a performance audit carried out under section 16 of the Public Audit Act 2001 December 2008 ISBN 978-0-478-32620-8 2 Contents Auditor-General’s overview 3 Our recommendations 4 Part 1 – Introduction 5 Part 2 – Planning for maintenance 7 Information about the state housing asset 7 Assessing the condition of state housing properties 8 Strategic position of long-term planning for maintenance 9 Planning and programming 10 Part 3 – Managing maintenance work 13 The system for carrying out maintenance 13 Setting priorities for maintenance work 15 Involving tenants and contractors in addressing maintenance issues 17 Staffi ng for maintenance functions 18 Part 4 – Monitoring and evaluating maintenance work 21 Monitoring maintenance work 21 Comparisons with the private sector 22 Improving maintenance performance and processes 23 Figures 1 Average response times for urgent health and safety and general responsive maintenance 22 Auditor-General’s overview 3 State housing is the largest publicly owned property portfolio in the country, with an estimated value in 2008 of $15.2 billion. Ensuring that the state housing stock is well-maintained is important for tenants and for protecting the value of these properties. Housing New Zealand Corporation (the Corporation) is the agency responsible for maintaining state housing. My staff carried out a performance audit to provide Parliament with assurance about the eff ectiveness of the systems and processes the Corporation uses to maintain state housing. -

Public Leadership—Perspectives and Practices

Public Leadership Perspectives and Practices Public Leadership Perspectives and Practices Edited by Paul ‘t Hart and John Uhr Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/public_leadership _citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Public leadership pespectives and practices [electronic resource] / editors, Paul ‘t Hart, John Uhr. ISBN: 9781921536304 (pbk.) 9781921536311 (pdf) Series: ANZSOG series Subjects: Leadership Political leadership Civic leaders. Community leadership Other Authors/Contributors: Hart, Paul ‘t. Uhr, John, 1951- Dewey Number: 303.34 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by John Butcher Images comprising the cover graphic used by permission of: Victorian Department of Planning and Community Development Australian Associated Press Australian Broadcasting Corporation Scoop Media Group (www.scoop.co.nz) Cover graphic based on M. C. Escher’s Hand with Reflecting Sphere, 1935 (Lithograph). Printed by University Printing Services, ANU Funding for this monograph series has been provided by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government Research Program. This edition © 2008 ANU E Press John Wanna, Series Editor Professor John Wanna is the Sir John Bunting Chair of Public Administration at the Research School of Social Sciences at The Australian National University. He is the director of research for the Australian and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG). -

Life Stories of Robert Semple

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. From Coal Pit to Leather Pit: Life Stories of Robert Semple A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of a PhD in History at Massey University Carina Hickey 2010 ii Abstract In the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography Len Richardson described Robert Semple as one of the most colourful leaders of the New Zealand labour movement in the first half of the twentieth century. Semple was a national figure in his time and, although historians had outlined some aspects of his public career, there has been no full-length biography written on him. In New Zealand history his characterisation is dominated by two public personas. Firstly, he is remembered as the radical organiser for the New Zealand Federation of Labour (colloquially known as the Red Feds), during 1910-1913. Semple’s second image is as the flamboyant Minister of Public Works in the first New Zealand Labour government from 1935-49. This thesis is not organised in a chronological structure as may be expected of a biography but is centred on a series of themes which have appeared most prominently and which reflect the patterns most prevalent in Semple’s life. The themes were based on activities which were of perceived value to Semple. Thus, the thematic selection was a complex interaction between an author’s role shaping and forming Semple’s life and perceived real patterns visible in the sources. -

Looking Back at Accident Compensation

351 THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL CONTEXT FOR THE CHANGES IN ACCIDENT COMPENSATION Robert Stephens* The changes in ACC after 1980 cannot be separated from profound changes in the shape and direction of New Zealand's political economy. Responding initially to the inherited economic imbalances in the 1970s, after 1984 the governing Labour Party launched a major restructuring of the economy and state administration. This paper describes the theories and objectives behind that transformation, as well as the generally disappointing results for economic performance and social equity. Further erosion of confidence in the state and dedication to market-driven policies continued well into the 1990s under the National Party. This paper documents the major trends during this entire period for employment, productivity, social inequality, and poverty. I INTRODUCTION Ever since its inception in 1973, the Accident Compensation Commission (ACC) has been both an administrative orphan, through its establishment as a quango rather than department of State,1 and a social outlier, based on social insurance principles rather than the tax-financed, flat-rate benefits of the existing social security system.2 However, the subsequent changes to ACC are integrally related to the wider political context that drove the economic and social changes faced by New Zealand during the last two decades of the twentieth century. During the 1980s, the successive Ministers of Finance, Robert D Muldoon (National) and Roger Douglas (Labour) had polar views on the objectives of policy, the appropriate economic theory, the role of markets, and the effectiveness of fiscal and monetary policy in maintaining economic * Robert Stephens, Senior Lecturer in Public Policy and Economics in the School of Government at Victoria University of Wellington.