Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Paso and the Twelve Travelers

Monumental Discourses: Sculpting Juan de Oñate from the Collected Memories of the American Southwest Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät IV – Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaften – der Universität Regensburg wieder vorgelegt von Juliane Schwarz-Bierschenk aus Freudenstadt Freiburg, Juni 2014 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Udo Hebel Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Volker Depkat CONTENTS PROLOGUE I PROSPECT 2 II CONCEPTS FOR READING THE SOUTHWEST: MEMORY, SPATIALITY, SIGNIFICATION 7 II.1 CULTURE: TIME (MEMORY) 8 II.1.1 MEMORY IN AMERICAN STUDIES 9 II.2 CULTURE: SPATIALITY (LANDSCAPE) 13 II.2.1 SPATIALITY IN AMERICAN STUDIES 14 II.3 CULTURE: SIGNIFICATION (LANDSCAPE AS TEXT) 16 II.4 CONCEPTUAL CONVERGENCE: THE SPATIAL TURN 18 III.1 UNITS OF INVESTIGATION: PLACE – SPACE – LANDSCAPE III.1.1 PLACE 21 III.1.2 SPACE 22 III.1.3 LANDSCAPE 23 III.2 EMPLACEMENT AND EMPLOTMENT 25 III.3 UNITS OF INVESTIGATION: SITE – MONUMENT – LANDSCAPE III.3.1 SITES OF MEMORY 27 III.3.2 MONUMENTS 30 III.3.3 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY 32 IV SPATIALIZING AMERICAN MEMORIES: FRONTIERS, BORDERS, BORDERLANDS 34 IV.1 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY I: THE LAND OF ENCHANTMENT 39 IV.1.1 THE TRI-ETHNIC MYTH 41 IV.2 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY II: HOMELANDS 43 IV.2.1 HISPANO HOMELAND 44 IV.2.2 CHICANO AZTLÁN 46 IV.3 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY III: BORDER-LANDS 48 V FROM THE SOUTHWEST TO THE BORDERLANDS: LANDSCAPES OF AMERICAN MEMORIES 52 MONOLOGUE: EL PASO AND THE TWELVE TRAVELERS 57 I COMING TO TERMS WITH EL PASO 60 I.1 PLANNING ‘THE CITY OF THE NEW OLD WEST’ 61 I.2 FOUNDATIONAL -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

ICAP-2020-Annual-Report.Pdf

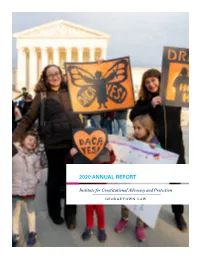

2020 ANNUAL REPORT OUR TEAM Professor Neal Katyal Faculty Chair Paul and Patricia Saunders Professor of National Security Law Professor Joshua A. Geltzer Executive Director and Visiting Professor of Law Professor Mary B. McCord Legal Director and Visiting Professor of Law Robert Friedman Senior Counsel Amy Marshak Senior Counsel Annie Owens Senior Counsel Nicolas Riley Senior Counsel Seth Wayne Senior Counsel Jonathan Backer Counsel Jennifer Safstrom Counsel Jonathan de Jong Litigation and Operations Clerk Photo credits: cover, Victoria Pickering (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0); inner front cover, pages 5 & 8, Sam Hollenshead; page 1, Matt Wade (CC BY-SA 2.0); page 2, Brent Futrell; page 3, Paul Sableman (CC BY 2.0); page 4, Cyndy Cox (CC BY- NC-SA 2.0); page 6, Stephen Velasco (CC BY-NC 2.0); page 7, Evelyn Hockstein; page 9 & back cover, GPA Photo Archive EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S LETTER Assaults on the separation of powers. Attacks on free speech. Antipathy toward immigrants. These and other threats to America’s constitutional system have defined much of the past year— and they are precisely what the Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection at Georgetown Law was built to tackle. We’ve been busy! In our third year, we’ve defended checks and balances between Congress and the President, pursued the safety of pre-trial detainees threatened by the COVID-19 pandemic, stood up for immigrants and their U.S. citizen children, brought new transparency to America’s courts, and continued to combat private militias that chill free speech and threaten public safety. And we’ve done it from federal district courts to the U.S. -

January / February 2008

We are pleased to debut the new look of Facilities Manager. This reflects the progressive direction of APPA and the character of our members. Inside you will find the same quality information all in an updated format. Enjoy the transformation! h ck I ilters Juggle less. Manage more. Run your educational institution's maintenance department efficiently and effectively with a CMMS that fits your every need. Whether you use one of TMA's desktop solutions, TMA eXpress, TMA WorkGroup, TMA Enterprise, or the most -■- ---■■- TMASYSTEMS powerful web-based system available for facilities - ·· Success Made Simple WebTMA, you can be assured that you're on the leading -- edge of facility maintenance management. 800.862.11 30 • www.tmasystems.com • sales@t masyst e ms.com The Lab of the The Lab of the Future: 30 Building Facilities that Attract Premier Faculty and Students By Tim R. Haley Busting the Limits 32 of Science Laboratory Economics By Robert C. Bush We're not talking about your old high school science lab with the traditional microscope, Bunsen burner, and beaker. Today's laboratories offer technology that w ill blow your mind and colleges are challenged to keep up with the times. Focusing on the Invisible By Tim R. Haley Reducing the Risk of 44 Dangerous Chemicals Getting into the Wrong Hands By Nancy Matthews How do you secure dangerous chemicals in an open learning environment? The U.S. Department of Homeland Security's quest to regulate the threat of chemical misuse extends to college and university facilities. Facilities Manager I january/february 2008 I 1 ••• From the Editor .........................................................4 ••••••••••• ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• • ••• Facilities Digest ......................................................... -

Appendix E High-Potential Historic Sites

APPENDIX E HIGH-POTENTIAL HISTORIC SITES National Trails System Act, SEC. 12. [16USC1251] As used in this Act: (1) The term “high-potential historic sites” means those historic sites related to the route, or sites in close proximity thereto, which provide opportunity to interpret the historic significance of the trail during the period of its major use. Criteria for consideration as high-potential sites include historic sig nificance, presence of visible historic remnants, scenic quality, and relative freedom from intrusion.. Mission Ysleta, Mission Trail Indian and Spanish architecture including El Paso, Texas carved ceiling beams called “vigas” and bell NATIONAL REGISTER tower. Era: 17th, 18th, and 19th Century Mission Ysleta was first erected in 1692. San Elizario, Mission Trail Through a series of flooding and fire, the mis El Paso, Texas sion has been rebuilt three times. Named for the NATIONAL REGISTER patron saint of the Tiguas, the mission was first Era: 17th, 18th, and 19th Century known as San Antonio de la Ysleta. The beauti ful silver bell tower was added in the 1880s. San Elizario was built first as a military pre sidio to protect the citizens of the river settle The missions of El Paso have a tremendous ments from Apache attacks in 1789. The struc history spanning three centuries. They are con ture as it stands today has interior pillars, sidered the longest, continuously occupied reli detailed in gilt, and an extraordinary painted tin gious structures within the United States and as ceiling. far as we know, the churches have never missed one day of services. -

The History of the Bexar County Courthouse by Sylvia Ann Santos

The History Of The Bexar County Courthouse By Sylvia Ann Santos An Occasional Publication In Regional History Under The Editorial Direction Of Felix D. Almaraz, Jr., The University Of Texas At San Antonio, For The Bexar County Historical Commission Dedicated To The People Of Bexar County EDITOR'S PREFACE The concept of a history of the Bexar County Courthouse originated in discussion sessions of the Bexar County Historical Commission. As a topic worthy of serious research, the concept fell within the purview of the History Appreciation Committee in the fall semester of 1976. Upon returning to The University of Texas at San Antonio from a research mission to Mexico City, I offered a graduate seminar in State and Local History in which Sylvia Ann Santos accepted the assignment of investigating and writing a survey history of the Bexar County Courthouse. Cognizant of the inherent difficulties in the research aspect, Mrs. Santos succeeded in compiling a bibliography of primary sources and in drafting a satisfactory outline and an initial draft of the manuscript. Following the conclusion of the seminar, Mrs. Santos continued the pursuit of elusive answers to perplexing questions. Periodically in Commission meetings, the status of the project came up for discussion, the usual response being that sound historical writing required time for proper perspective. Finally, in the fall of 1978, after endless hours of painstaking research in old public records, private collections, and microfilm editions of newspapers, Mrs. Santos submitted the manuscript for editorial review and revision. This volume is a contribution to the Bexar County Historical Commission's series of Occasional Publications in Regional History. -

From a Grain of Mustard Seed by Cynthia Davis

FROM A GRAIN OF MUSTARD SEED BY CYNTHIA DAVIS ISBN 978-0-557-02763-7 THE MUSTARD SEED IS PLANTED 1872-1882 The seed that became St. John’s Episcopal Cathedral was found in the hearts of the small group of faithful Episcopalians who settled in Albuquerque. As a minority of the population, the Anglos found comfort in the familiarity of reading the 1789 Book of Common Prayer, the King James Bible, and the Calvary Cathechism. Very likely they followed the mandate in the Prayer Book stating, “The Psalter shall be read through once every month, as it is there appointed, both for Morning and for Evening Prayer.”i Under the strong spiritual direction of the Rev. Henry Forrester, both St. John’s and missions around the District would be planted, land purchased, and churches built. Other seeds were being planted in Albuquerque. Various denominations built churches in the midst of the homes where the new arrivals lived. Members could easily walk to the church of their choice. Many corner lots were taken up with small places of worship. Some Anglos attended the Methodist church built of adobe in 1880 at Third and Lead. Dr. Sheldon Jackson, established First Presbyterian Church in 1880. A one-room church was built at Fifth and Silver two years later under Rev. James Menaul. It was enlarged in 1905, and after a fire in 1938, the building was rebuilt and improved. (In 1954 it moved to 215 Locust.)ii St. Paul’s Lutheran Church was not built until 1891 at Sixth and Silver. The Rev. -

A Preservation Plan for the Fred Harvey Houses

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2010 Branding the Southwest: A Preservation Plan for the Fred Harvey Houses Patrick W. Kidd University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Kidd, Patrick W., "Branding the Southwest: A Preservation Plan for the Fred Harvey Houses" (2010). Theses (Historic Preservation). 144. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/144 Suggested Citation: Kidd, Patrick W. (2010) "Branding the Southwest: A Preservation Plan for the Fred Harvey Houses." (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/144 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Branding the Southwest: A Preservation Plan for the Fred Harvey Houses Keywords Historic Preservation; Southwest, Railroad Disciplines Architecture | Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Suggested Citation: Kidd, Patrick W. (2010) "Branding the Southwest: A Preservation Plan for the Fred Harvey Houses." (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/144 BRANDING THE SOUTHWEST: A PRESERVATION PLAN FOR THE FRED HARVEY HOUSES Patrick W. Kidd A Thesis in Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2010 ____________________________ Advisor Dr. Aaron V. Wunsch, PhD Lecturer in Architectural History ____________________________ Program Chair Dr. Randall F. Mason, PhD Associate Professor This work is dedicated to all those who strive to preserve and promote our rich rail heritage and to make it available to future generations. -

San Antonio San Antonio, Texas

What’s ® The Cultural Landscape Foundation ™ Out There connecting people to places tclf.org San Antonio San Antonio, Texas Welcome to What’s Out There San Antonio, San Pedro Springs Park, among the oldest public parks in organized by The Cultural Landscape Foundation the country, and the works of Dionicio Rodriguez, prolificfaux (TCLF) in collaboration with the City of San Antonio bois sculptor, further illuminate the city’s unique landscape legacy. Historic districts such as La Villita and King William Parks & Recreation and a committee of local speak to San Antonio’s immigrant past, while the East Side experts, with generous support from national and Cemeteries and Ellis Alley Enclave highlight its significant local partners. African American heritage. This guidebook provides photographs and details of 36 This guidebook is a complement to TCLF’s digital What’s Out examples of the city's incredible landscape legacy. Its There San Antonio Guide (tclf.org/san-antonio), an interactive publication is timed to coincide with the celebration of San online platform that includes the enclosed essays plus many Antonio's Tricentennial and with What’s Out There Weekend others, as well as overarching narratives, maps, historic San Antonio, November 10-11, 2018, a weekend of free, photographs, and biographical profiles. The guide is one of expert-led tours. several online compendia of urban landscapes, dovetailing with TCLF’s web-based What’s Out There, the nation’s most From the establishment of the San Antonio missions in the comprehensive searchable database of historic designed st eighteenth century, to the 21 -century Mission and Museum landscapes. -

Autozone OFFERING MEMORANDUM San Antonio, Texas

AutoZone OFFERING MEMORANDUM San Antonio, Texas Cassidyu Andrew Bogardus Christopher Sheldon Douglas Longyear Ed Colson, Jr. 415-677-0421 415-677-0441 415-677-0458 858-546-5423 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Lic #00913825 Lic #01806345 Lic #00829911 TX Lic #635820 Disclaimer The information contained in this marketing brochure (“Materials”) is proprietary The information contained in the Materials has been obtained by Agent from sources and confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the person or entity receiving believed to be reliable; however, no representation or warranty is made regarding the the Materials from Cassidy Turley Northern California (“Agent”). The Materials are accuracy or completeness of the Materials. Agent makes no representation or warranty intended to be used for the sole purpose of preliminary evaluation of the subject regarding the Property, including but not limited to income, expenses, or financial property/properties (“Property”) for potential purchase. performance (past, present, or future); size, square footage, condition, or quality of the land and improvements; presence or absence of contaminating substances The Materials have been prepared to provide unverified summary financial, property, (PCB’s, asbestos, mold, etc.); compliance with laws and regulations (local, state, and and market information to a prospective purchaser to enable it to establish a preliminary federal); or, financial condition or business prospects of any tenant (tenants’ intentions level of interest in potential purchase of the Property. The Materials are not to be regarding continued occupancy, payment of rent, etc). A prospective purchaser must considered fact. -

Historic Office & Restaurant Space Adjacent to San Antonio's Iconic Riverwalk

BEAUTIFULLY RESTORED Historic Office & Restaurant Space NOVEMBER 2022 DELIVERY Adjacent to San Antonio’s Iconic Riverwalk SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS Four-story historic office building containing 26,874 SF Three upper floors of office space, ground level restaurant / bar space Surrounded by government offices, hotels, restaurants and mixed-use residential 39 million people visit San Antonio annually and the Riverwalk is Texas’ number one tourist attraction. 100 Years of100 Years Riverwalk History - Beautifully Restored SAN ANTONIO CITY HALL SAN FERNANDO CATHEDRAL PLAZA DE LAS ISLAS CANARIAS S FLORES ST CADENA REEVES MARKET STREET JUSTICE CENTER BEXAR COUNTY COURTHOUSE MAIN PLAZA DIRECTLY ACROSS FROM COMMERCE STREET BEXAR COUNTY COURTHOUSE WITHIN BLOCKS OF MANY FEDERAL, COUNTY AND CITY GOVERNMENT OFFICES ONE BLOCK FROM MARKET STREET WALKING DISTANCE TO NUMEROUS HOTELS AND RESTAURANTS MAIN PLAZA AMPLE PARKING RESTAURANT AND OFFICE VIEWS OVERLOOKING RIVERWALK VILLITA STREET PRIME SAN ANTONIO RIVERWALK LOCATION Tower Life Building Drury Plaza Cadena Reeves Hotel Justice Center Bexar County Granada Courthouse Riverwalk Plaza Homes Hotel Main Plaza E Nueva St Tower of the Americas Tower Life Hemisfair Building Park Alamodome IMAX Theatre Henry B. Gonzalez The Alamo Convention Center 200 MAIN PLAZA WYNDHAM RIVERWALK E Pecan St WESTON P CENTRE THE CHILDREN’S P HOSPITAL OF SAN ANTONIO N SANTA ROSA INT’L BANK OF P COMMERCE EMBASSY SHERATON SUITES GUNTER HOUSTON ST HOTEL MAJESTIC VALENCIA EMPIRE THEATRE MILAM PARK THEATRE HOME 2 HOLIDAY P SUITES INN MARRIOTT -

La Villita Earthworks

\ LA VILLITA EARTHWORKS. \. (41 ax 677): San Antonio, Texas .' '. A Preliminary Report of Jnvestigations of Mexican Siege Works at the Battle of the Alamo .. Assembled by Joseph H. Labadie With Contributions By Kenneth M. BrowfjI,Anne A. Fox, . Joseph H. Labadie, Sarhuel P. Nesmith, Paul S. Storch, David b. Turner, Shirley Van der Veer, and Alisa J. Winkler Center for Archaeological Research The University of Texas at San Antonio Archaeological Survey Report r No.1 59 1986 © 1981 State of T~xas COVER ILLUSTRATION: Lock from India Pattern Brown Bess musket (ca. 1809-1815), typical of those carried by the Mexican infantry at the battle of the Alamo. Cover illustratiDn by Kenneth M. Brown. / / LA VILLITA EARTHWORKS (41 BX 677): SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS A Preliminary Report of Investigations of Mexican Siege Works at the Battle of the Alamo Assembled by Joseph H. Labadie With contributions by Kenneth M. Brown, Anne A. Fox, Joseph H. Labadie, Samuel P. Nesmith, Paul S. Storch, David D. Turner, Shirley Van der Veer, and Al isa J. Winkler Texas Antiquities Committee Permit No. 480 Thomas R. Hester, Principal Investigator Center for Archaeological Research The University of Texas at San Antonio® Archaeological Survey Report, No. 159 1986 The following information is provided in accordance with the General Rul es of Practice and Procedure, Chapter 41.11 (Investigative Reports), Texas Antiquities Committee: 1. Type of investigation: monitoring of foundation excavations for the relocation of the Fairmount Hotel; 2. Project name: Fairmount I Project; 3. County: Bexar; 4. Principal investigator: Thomas R. Hester; co-principal investigator: Jack D.