Appendix E High-Potential Historic Sites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Environmental History of the Middle Rio Grande Basin

United States Department of From the Rio to the Sierra: Agriculture Forest Service An Environmental History of Rocky Mountain Research Station the Middle Rio Grande Basin Fort Collins, Colorado 80526 General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-5 Dan Scurlock i Scurlock, Dan. 1998. From the rio to the sierra: An environmental history of the Middle Rio Grande Basin. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-5. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 440 p. Abstract Various human groups have greatly affected the processes and evolution of Middle Rio Grande Basin ecosystems, especially riparian zones, from A.D. 1540 to the present. Overgrazing, clear-cutting, irrigation farming, fire suppression, intensive hunting, and introduction of exotic plants have combined with droughts and floods to bring about environmental and associated cultural changes in the Basin. As a result of these changes, public laws were passed and agencies created to rectify or mitigate various environmental problems in the region. Although restoration and remedial programs have improved the overall “health” of Basin ecosystems, most old and new environmental problems persist. Keywords: environmental impact, environmental history, historic climate, historic fauna, historic flora, Rio Grande Publisher’s Note The opinions and recommendations expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USDA Forest Service. Mention of trade names does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the Federal Government. The author withheld diacritical marks from the Spanish words in text for consistency with English punctuation. Publisher Rocky Mountain Research Station Fort Collins, Colorado May 1998 You may order additional copies of this publication by sending your mailing information in label form through one of the following media. -

The Federal Indian Policy in New Mexico, 1858–1880, IV

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 13 Number 3 Article 4 7-1-1938 The Federal Indian Policy in New Mexico, 1858–1880, IV Frank D. Reeve Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Reeve, Frank D.. "The Federal Indian Policy in New Mexico, 1858–1880, IV." New Mexico Historical Review 13, 3 (1938). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol13/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. I J ! THE FEDERAL INDIAN POLICY IN NEW MEXICO 1858-1880, IV By FRANK D. REEVE CHAPTER IX MESCALERO APACHE The Southern Apache Indians in New Mexico were divided into two groups: The Gila, that lived west of the Rio Grande, and the Mescaleros that lived east of the river, in the White and Sacramento mountains. The Mescaleros, about 600 or 700 in number, suffered from internal dissen sion and had split into two bands; the more troublesome group, known by the name of the Agua Nuevo band, under chiefs Mateo and Verancia, lived in the vicinity of Dog Canyon, in the Sacramento mountains. The White moun tain group under Cadette constituted the bulk of the tribe and busied themselves part of the time with farming opera tions at Alamogordo, about seventy miles southwest of Fort Stanton and west of the Sacramento mountains.! The Mescaleros constituted the same problem as did the other Indian tribes, and Superintendent CoIlins pro posed to adopt the same procedure in dealing with them; namely, removal from the settlements to a reservation where they would be out of contact with the white settlers. -

El Paso and the Twelve Travelers

Monumental Discourses: Sculpting Juan de Oñate from the Collected Memories of the American Southwest Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät IV – Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaften – der Universität Regensburg wieder vorgelegt von Juliane Schwarz-Bierschenk aus Freudenstadt Freiburg, Juni 2014 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Udo Hebel Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Volker Depkat CONTENTS PROLOGUE I PROSPECT 2 II CONCEPTS FOR READING THE SOUTHWEST: MEMORY, SPATIALITY, SIGNIFICATION 7 II.1 CULTURE: TIME (MEMORY) 8 II.1.1 MEMORY IN AMERICAN STUDIES 9 II.2 CULTURE: SPATIALITY (LANDSCAPE) 13 II.2.1 SPATIALITY IN AMERICAN STUDIES 14 II.3 CULTURE: SIGNIFICATION (LANDSCAPE AS TEXT) 16 II.4 CONCEPTUAL CONVERGENCE: THE SPATIAL TURN 18 III.1 UNITS OF INVESTIGATION: PLACE – SPACE – LANDSCAPE III.1.1 PLACE 21 III.1.2 SPACE 22 III.1.3 LANDSCAPE 23 III.2 EMPLACEMENT AND EMPLOTMENT 25 III.3 UNITS OF INVESTIGATION: SITE – MONUMENT – LANDSCAPE III.3.1 SITES OF MEMORY 27 III.3.2 MONUMENTS 30 III.3.3 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY 32 IV SPATIALIZING AMERICAN MEMORIES: FRONTIERS, BORDERS, BORDERLANDS 34 IV.1 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY I: THE LAND OF ENCHANTMENT 39 IV.1.1 THE TRI-ETHNIC MYTH 41 IV.2 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY II: HOMELANDS 43 IV.2.1 HISPANO HOMELAND 44 IV.2.2 CHICANO AZTLÁN 46 IV.3 LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY III: BORDER-LANDS 48 V FROM THE SOUTHWEST TO THE BORDERLANDS: LANDSCAPES OF AMERICAN MEMORIES 52 MONOLOGUE: EL PASO AND THE TWELVE TRAVELERS 57 I COMING TO TERMS WITH EL PASO 60 I.1 PLANNING ‘THE CITY OF THE NEW OLD WEST’ 61 I.2 FOUNDATIONAL -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

ICAP-2020-Annual-Report.Pdf

2020 ANNUAL REPORT OUR TEAM Professor Neal Katyal Faculty Chair Paul and Patricia Saunders Professor of National Security Law Professor Joshua A. Geltzer Executive Director and Visiting Professor of Law Professor Mary B. McCord Legal Director and Visiting Professor of Law Robert Friedman Senior Counsel Amy Marshak Senior Counsel Annie Owens Senior Counsel Nicolas Riley Senior Counsel Seth Wayne Senior Counsel Jonathan Backer Counsel Jennifer Safstrom Counsel Jonathan de Jong Litigation and Operations Clerk Photo credits: cover, Victoria Pickering (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0); inner front cover, pages 5 & 8, Sam Hollenshead; page 1, Matt Wade (CC BY-SA 2.0); page 2, Brent Futrell; page 3, Paul Sableman (CC BY 2.0); page 4, Cyndy Cox (CC BY- NC-SA 2.0); page 6, Stephen Velasco (CC BY-NC 2.0); page 7, Evelyn Hockstein; page 9 & back cover, GPA Photo Archive EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S LETTER Assaults on the separation of powers. Attacks on free speech. Antipathy toward immigrants. These and other threats to America’s constitutional system have defined much of the past year— and they are precisely what the Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection at Georgetown Law was built to tackle. We’ve been busy! In our third year, we’ve defended checks and balances between Congress and the President, pursued the safety of pre-trial detainees threatened by the COVID-19 pandemic, stood up for immigrants and their U.S. citizen children, brought new transparency to America’s courts, and continued to combat private militias that chill free speech and threaten public safety. And we’ve done it from federal district courts to the U.S. -

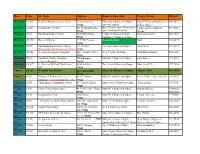

Community Service Worksheet

Place Code Site Name Address Hours of Operation Contact Person Phone # Westside CS116 Franklin Mountains State Park Transmountain Mon-Sun 8:00am to 5:00pm Robert Pichardo/Raul Gomez 566-6441 79912 MALES ONLY & Erika Rubio Westside CS127 Galatzan Rec Center 650 Wallenberg Dr. Mon - Th 1pm to 9pm; Friday 1pm to Carlos Apodaca Robert 581-5182 79912 6pm; Saturday 9am to 2pm Owens Westside CS27 Don Haskins Rec Center 7400 High Ridge Fridays 2:00pm to 6:00pm Rick Armendariz 587-1623 79912 Saturdays 9:00am to 2:00pm Westside CS140 Rescue Mission 1949 W. Paisano Residents Only Staff 532-2575 79922 Westside CS101 Environmental Services (West) 121 Atlantic Tue-Sat 8:00am to 4:00pm Jose Flores 873-8633 Martin Sandiego/Main Supervisor 472-4844 79922 Westside CS142 Westside Regional Command 4801 Osborne Drive Wed 7:00am-10:00am Orlando Hernandez 585-6088 79922 Canutillo CS111 Canutillo County Nutrition 7361 Bosque Mon-Fri 9:00am to 1:00pm Irma Torres 877-2622 (close to Westside) 79835 Canutillo CS117 St. Vincent De Paul Thrift Store 6950 3rd Street Tues-Sat 10:00am to 6:00pm Mari Cruz P. Lee 877-7030 (W) 79835 Vinton CS143 Westside Field Office 435 Vinton Rd Mon-Fri 8:00am to 6:00pm. Support Staff 886-1040 79821 Vinton CS67 Village of Vinton-(close to 436 E. Vinton Mon-Fri 8:00am to 4:00pm Perch Valdez, José Alarcón 383-6993 Anthony) avail for light duty- No 79821 Central- CS53 Chihuahuita Community Center 417 Charles Road Mon - Fri 11:00am to 6:00pm Patricia Rios 533-6909 DT 79901 Central- CS11 Civic Center Maintenance #1 Civic Center Plaza Mon-Fri 6:00am to 4:00pm Manny Molina 534-0626/ DT 79901 534-0644 Central- CS14 Opportunity Center 1208 Myrtle Mon-Fri 6:00am to 6:00p.m. -

The Lower Permian Abo Formation in the Fra Cristobal and Caballo Mountains, Sierra County, New Mexico Spencer G

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/63 The Lower Permian Abo Formation in the Fra Cristobal and Caballo Mountains, Sierra County, New Mexico Spencer G. Lucas, Karl Krainer, Dan S. Chaney, William A. DiMichele, Sebastian Voigt, David S. Berman, and Amy C. Henrici, 2012, pp. 345-376 in: Geology of the Warm Springs Region, Lucas, Spencer G.; McLemore, Virginia T.; Lueth, Virgil W.; Spielmann, Justin A.; Krainer, Karl, New Mexico Geological Society 63rd Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 580 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 2012 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. -

The Cretaceous System in Central Sierra County, New Mexico

The Cretaceous System in central Sierra County, New Mexico Spencer G. Lucas, New Mexico Museum of Natural History, Albuquerque, NM 87104, [email protected] W. John Nelson, Illinois State Geological Survey, Champaign, IL 61820, [email protected] Karl Krainer, Institute of Geology, Innsbruck University, Innsbruck, A-6020 Austria, [email protected] Scott D. Elrick, Illinois State Geological Survey, Champaign, IL 61820, [email protected] Abstract (part of the Dakota Formation, Campana (Fig. 1). This is the most extensive outcrop Member of the Tres Hermanos Formation, area of Cretaceous rocks in southern New Upper Cretaceous sedimentary rocks are Flying Eagle Canyon Formation, Ash Canyon Mexico, and the exposed Cretaceous sec- Formation, and the entire McRae Group). A exposed in central Sierra County, southern tion is very thick, at about 2.5 km. First comprehensive understanding of the Cretaceous New Mexico, in the Fra Cristobal Mountains, recognized in 1860, these Cretaceous Caballo Mountains and in the topographically strata in Sierra County allows a more detailed inter- pretation of local geologic events in the context strata have been the subject of diverse, but low Cutter sag between the two ranges. The ~2.5 generally restricted, studies for more than km thick Cretaceous section is assigned to the of broad, transgressive-regressive (T-R) cycles of 150 years. (ascending order) Dakota Formation (locally deposition in the Western Interior Seaway, and includes the Oak Canyon [?] and Paguate also in terms of Laramide orogenic -

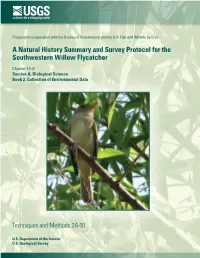

A Natural History Summary and Survey Protocol for the Southwestern Willow Flycatcher

Prepared in cooperation with the Bureau of Reclamation and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service A Natural History Summary and Survey Protocol for the Southwestern Willow Flycatcher Chapter 10 of Section A, Biological Science Book 2, Collection of Environmental Data Techniques and Methods 2A-10 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Southwestern Willow Flycatcher. Photograph taken by Susan Sferra, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. A Natural History Summary and Survey Protocol for the Southwestern Willow Flycatcher By Mark K. Sogge, U.S. Geological Survey; Darrell Ahlers, Bureau of Reclamation; and Susan J. Sferra, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Chapter 10 of Section A, Biological Science Book 2, Collection of Environmental Data Prepared in cooperation with the Bureau of Reclamation and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Techniques and Methods 2A-10 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2010 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

Geoarchaeology of the Mockingbird Gap (Clovis) Site, Jornada Del Muerto, New Mexico

GEA243_07_20265.qxd 4/3/09 3:52 PM Page 348 Geoarchaeology of the Mockingbird Gap (Clovis) Site, Jornada del Muerto, New Mexico Vance T. Holliday,1,* Bruce B. Huckell,2 Robert H. Weber,3 Marcus J. Hamilton,4 William T. Reitze,5 and James H. Mayer6 1Departments of Anthropology and Geosciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721 2Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131 3New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, Socorro, NM (Deceased) 4Department of Anthropology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131 5Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721 6Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721 The Mockingbird Gap site is one of the largest Clovis sites in the western United States, yet it remains poorly known after it was tested in 1966–1968. Surface collecting and mapping of the site revealed a dense accumulation of Clovis lithic debris stretching along Chupadera Draw, which drains into the Jornada del Muerto basin. We conducted archaeological testing and geoarchaeological coring to assess the stratigraphic integrity of the site and gain clues to the paleoenvironmental conditions during the Clovis occupation. The 1966–1968 excavations were in stratified Holocene eolian sand and thus that assemblage was from a disturbed content. An intact Clovis occupation was found elsewhere in the site, embedded in the upper few cen- timeters of a well-developed buried Bt horizon formed in eolian sand, representing the regional Clovis landscape. Coring in Chupadera Draw revealed ϳ11 m of fill spanning the past ϳ11,000 14C years. The stratified deposits provide evidence of flowing and standing water on the floor of the draw during Clovis times, a likely inducement to settlement. -

Global Lithium Sources—Industrial Use and Future in the Electric Vehicle Industry: a Review

resources Review Global Lithium Sources—Industrial Use and Future in the Electric Vehicle Industry: A Review Laurence Kavanagh * , Jerome Keohane, Guiomar Garcia Cabellos, Andrew Lloyd and John Cleary EnviroCORE, Department of Science and Health, Institute of Technology Carlow, Kilkenny, Road, Co., R93-V960 Carlow, Ireland; [email protected] (J.K.); [email protected] (G.G.C.); [email protected] (A.L.); [email protected] (J.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 July 2018; Accepted: 11 September 2018; Published: 17 September 2018 Abstract: Lithium is a key component in green energy storage technologies and is rapidly becoming a metal of crucial importance to the European Union. The different industrial uses of lithium are discussed in this review along with a compilation of the locations of the main geological sources of lithium. An emphasis is placed on lithium’s use in lithium ion batteries and their use in the electric vehicle industry. The electric vehicle market is driving new demand for lithium resources. The expected scale-up in this sector will put pressure on current lithium supplies. The European Union has a burgeoning demand for lithium and is the second largest consumer of lithium resources. Currently, only 1–2% of worldwide lithium is produced in the European Union (Portugal). There are several lithium mineralisations scattered across Europe, the majority of which are currently undergoing mining feasibility studies. The increasing cost of lithium is driving a new global mining boom and should see many of Europe’s mineralisation’s becoming economic. The information given in this paper is a source of contextual information that can be used to support the European Union’s drive towards a low carbon economy and to develop the field of research. -

New Mexico Archaeology New Mexico Archaeology

NTheNew ewNewsletter MMexicoexico of the Friends AArchaeology rchaeologyof Archaeology November 2010 From The Director Treasury Report Eric Blinman, OAS Director, THANK YOU! and John Karon, FOA Treasurer FOA support for the furniture and fixture campaign for the Center for FOA is an educational, research, and fund raising New Mexico Archaeology (CNMA) has been overwhelming! With organization; the latter supports the former. FOA pledges and contributions, we have reached our goal of $75,000. doesn’t charge dues for membership, so if you are a More than 100 people have contributed, with contributions honoring member of the MNM Foundation and express inter- the memories of Marjorie Mizerak, Marshall Clinard, and Jerome est in archaeology you are an FOA member. Lipetzky. Most of you knew Marj and her surviving husband, Bob. FOA raises funds through specific events, They have been long term volunteers for OAS and trip leaders lectures and trips as well as donations from indi- for FOA. Marshall was the husband of Arlen Clinard, an OAS viduals. The Endowment and the Center for New volunteer, and Marshall was the last surviving member of Edgar Mexico Archaeology furniture and fixtures cam- Lee Hewett’s Chaco field schools. Jerry Lipetzky was a high school paign are separate, and their status is summarized in teacher who created the teaching simulations DIG and DIG 2 that are “From the Director”. This report provides a snap- used nation-wide. He sparked my interest in archaeology in 1967, shot of FOA fund raising and distributions over the and he is responsible for initiating the careers of at least six Ph.D.