La Villita Earthworks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of the Bexar County Courthouse by Sylvia Ann Santos

The History Of The Bexar County Courthouse By Sylvia Ann Santos An Occasional Publication In Regional History Under The Editorial Direction Of Felix D. Almaraz, Jr., The University Of Texas At San Antonio, For The Bexar County Historical Commission Dedicated To The People Of Bexar County EDITOR'S PREFACE The concept of a history of the Bexar County Courthouse originated in discussion sessions of the Bexar County Historical Commission. As a topic worthy of serious research, the concept fell within the purview of the History Appreciation Committee in the fall semester of 1976. Upon returning to The University of Texas at San Antonio from a research mission to Mexico City, I offered a graduate seminar in State and Local History in which Sylvia Ann Santos accepted the assignment of investigating and writing a survey history of the Bexar County Courthouse. Cognizant of the inherent difficulties in the research aspect, Mrs. Santos succeeded in compiling a bibliography of primary sources and in drafting a satisfactory outline and an initial draft of the manuscript. Following the conclusion of the seminar, Mrs. Santos continued the pursuit of elusive answers to perplexing questions. Periodically in Commission meetings, the status of the project came up for discussion, the usual response being that sound historical writing required time for proper perspective. Finally, in the fall of 1978, after endless hours of painstaking research in old public records, private collections, and microfilm editions of newspapers, Mrs. Santos submitted the manuscript for editorial review and revision. This volume is a contribution to the Bexar County Historical Commission's series of Occasional Publications in Regional History. -

Stumpf (Ella Ketcham Daggett) Papers, 1866, 1914-1992

Texas A&M University-San Antonio Digital Commons @ Texas A&M University-San Antonio Finding Aids: Guides to the Collection Archives & Special Collections 2020 Stumpf (Ella Ketcham Daggett) Papers, 1866, 1914-1992 DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tamusa.edu/findingaids Recommended Citation DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio, "Stumpf (Ella Ketcham Daggett) Papers, 1866, 1914-1992" (2020). Finding Aids: Guides to the Collection. 160. https://digitalcommons.tamusa.edu/findingaids/160 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives & Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Texas A&M University-San Antonio. It has been accepted for inclusion in Finding Aids: Guides to the Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Texas A&M University-San Antonio. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ella Ketcham Daggett Stumpf Papers, 1866, 1914-1992 Descriptive Summary Creator: Stumpf, Ella Ketcham Daggett (1903-1993) Title: Ella Ketcham Daggett Stumpf Papers, 1866-1914-1992 Dates: 1866, 1914-1992 Creator Ella Ketcham Daggett was an active historic preservationist and writer Abstract: of various subjects, mainly Texas history and culture. Content Consisting primarily of short manuscripts and the source material Abstract: gathered in their production, the Ella Ketcham Daggett Stumpf Papers include information on a range of topics associated with Texas history and culture. Identification: Col 6744 Extent: 16 document and photograph boxes, 1 artifacts box, 2 oversize boxes, 1 oversize folder Language: Materials are in English Repository: DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio Biographical Note A fifth-generation Texan, Ella Ketcham Daggett was born on October 11, 1903 at her grandmother’s home in Palestine, Texas to Fred D. -

La Villita Historic District 01/20/1972

Dist. 20, Rep. Henry B. Gonzales Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Texas NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Bexar INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) 1. NAME COMMON : La Villita Historic District AT«JD/OR HISTORIC: [2. LOCATION STREET AND NUMBER: Bounded by Durango, Navarro, Alamo and San Antonio River CITY OR TOWN: San Antonio Texas JM.S Be?^ar 1122. 3. CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC [2J District • Building • Public Public Acquisition: Occupied Yes: Restricted • Site • Structure r~| Private I 1 In Process I I Unoccupied I I Unrestricted • Object S Both j Being Considered I I Preservation work in progress • No U PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) r~] Agricultural 1 1 Government • Pork I i Transportation I I Comments 1 I Commercial Industrial • Private Residence Other (Specify) I ) Educational • Military I I Religious various groups (arts) [ I Entertainment Museum I 1 Scientific have offices here f4. OWNER OF PROPERTY OWNER'S NAME: Multiple ownership STREET AND NUMBER: Cl TY OR TOWN: STATE: / _ 5. LOCATtON OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: " ' . r--r San Antonio City Hall STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN : San Antonio Texas 048 6. REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS ± TITLE OF suRVEY:Soine, fout not all buildings, are listed in Historic American Rnil dings Sui-vf^y O DATE OF SURVEY; fjt Federal • Stote • County • Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: z Library of Congress STREET AND NUMBER: o z CITY OR TOWN: Washington -QOa (See continuation sheet #1) 7. -

San Antonio San Antonio, Texas

What’s ® The Cultural Landscape Foundation ™ Out There connecting people to places tclf.org San Antonio San Antonio, Texas Welcome to What’s Out There San Antonio, San Pedro Springs Park, among the oldest public parks in organized by The Cultural Landscape Foundation the country, and the works of Dionicio Rodriguez, prolificfaux (TCLF) in collaboration with the City of San Antonio bois sculptor, further illuminate the city’s unique landscape legacy. Historic districts such as La Villita and King William Parks & Recreation and a committee of local speak to San Antonio’s immigrant past, while the East Side experts, with generous support from national and Cemeteries and Ellis Alley Enclave highlight its significant local partners. African American heritage. This guidebook provides photographs and details of 36 This guidebook is a complement to TCLF’s digital What’s Out examples of the city's incredible landscape legacy. Its There San Antonio Guide (tclf.org/san-antonio), an interactive publication is timed to coincide with the celebration of San online platform that includes the enclosed essays plus many Antonio's Tricentennial and with What’s Out There Weekend others, as well as overarching narratives, maps, historic San Antonio, November 10-11, 2018, a weekend of free, photographs, and biographical profiles. The guide is one of expert-led tours. several online compendia of urban landscapes, dovetailing with TCLF’s web-based What’s Out There, the nation’s most From the establishment of the San Antonio missions in the comprehensive searchable database of historic designed st eighteenth century, to the 21 -century Mission and Museum landscapes. -

About San Antonio, Texas

Photos courtesy of San Antonio Convention & Visitors Bureau Photos courtesy of San Antonio Convention ABOUT SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS San Antonio is one of the oldest cities settled in the most robust economies in the country. 1731 by 16 Spanish families from the Canary Islands. One of the fastest-growing cities, San Antonio has The site of San Antonio was first visited in 1691 by a also been recognized as one of the best places to buy Franciscan friar on the feast day of St. Anthony and real estate, one of the best places to retire, one of the was named San Antonio de Padua in his honor. most recession-proof economies, and one of the best Native Americans, Colonial Spain, the Canary Islands, places for entry level jobs. Old Mexico, Germans, the Wild West, and the Deep South cross paths in San Antonio, where tradition DID YOU KNOW? and cosmopolitan style sidle up for a one-of-a-kind- > San Antonio is the third fastest-growing city in America ride. and the 7th-largest U.S. city. Many people are familiar with San Antonio’s > San Antonio has 68 miles of urban hiking/biking trails. famed River Walk, and of course the historic Alamo, > The 2nd-oldest park in the U.S. is located in San but the city and its region offer so much more. San Antonio - San Pedro Park. Antonio has been a city of innovation and steady > San Antonio has the 3rd-largest zoo in the U.S., with growth for decades, while its cultural blend of people over 3,500 animals. -

Autozone OFFERING MEMORANDUM San Antonio, Texas

AutoZone OFFERING MEMORANDUM San Antonio, Texas Cassidyu Andrew Bogardus Christopher Sheldon Douglas Longyear Ed Colson, Jr. 415-677-0421 415-677-0441 415-677-0458 858-546-5423 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Lic #00913825 Lic #01806345 Lic #00829911 TX Lic #635820 Disclaimer The information contained in this marketing brochure (“Materials”) is proprietary The information contained in the Materials has been obtained by Agent from sources and confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the person or entity receiving believed to be reliable; however, no representation or warranty is made regarding the the Materials from Cassidy Turley Northern California (“Agent”). The Materials are accuracy or completeness of the Materials. Agent makes no representation or warranty intended to be used for the sole purpose of preliminary evaluation of the subject regarding the Property, including but not limited to income, expenses, or financial property/properties (“Property”) for potential purchase. performance (past, present, or future); size, square footage, condition, or quality of the land and improvements; presence or absence of contaminating substances The Materials have been prepared to provide unverified summary financial, property, (PCB’s, asbestos, mold, etc.); compliance with laws and regulations (local, state, and and market information to a prospective purchaser to enable it to establish a preliminary federal); or, financial condition or business prospects of any tenant (tenants’ intentions level of interest in potential purchase of the Property. The Materials are not to be regarding continued occupancy, payment of rent, etc). A prospective purchaser must considered fact. -

The San Antonio River Walk

Independence Title LEARN MORE IndependenceTitle.com Non-motorized water craft are allowed in three areas of the River Walk. Please ATLANTA AVE, San Antonio note, these trails are not connected and users will need to use the proper access The Blue Hole points to move between them over land. University of the (Headwaters Museum Incarnate Word Sanctuary) • Historic Downtown Section, near the King William District, between Nueva and E. Hildebrand Ave. SAN PEDRO 19 Devine Rd. of Art South Alamo Street, with the access point off of East Guenther Street. Devine Rd. San Antonio ERIE AVE. T 281 Shook Ave. Shook Ave. e ul Zoo • Eagleland Section between South Alamo Street and the railroad bridge north of riv eta Ave. WARREN D Lone Star Boulevard, with the access point just north of the railroad bridge m iu d Alamo a Japanese t t Stadium Witte S • Mission Reach from Lone Star Boulevard to south of Loop 410 near Mission S Tea Garden r. W. JONES ine D Museum Espada. Trinity Alp . r University D Sunken Garden e MCCULLOUGH AVENUE g Rivers are ever-changing, dynamic systems d Theater i r n e with inherent dangers, so please k c a r remember the following safety tips: 281 B Broadway CAMDEN ,QÁDWDEOHERDWVRUZDWHUFUDIWDQG Red Oak Rd. S.A. Botanical Garden MARSHALL paddle boats are not allowed. Brackenridge Park HILL GROVE W. Mulberry Ave. E. Mulberry Ave. QUINCY Ave San Pedro BROOKLYN AVE • Make sure your paddling skills are equal Davis Park McCullough Ave. McCullough to the water conditions and proceed at A Avenue B ue River Rd. -

Historic Office & Restaurant Space Adjacent to San Antonio's Iconic Riverwalk

BEAUTIFULLY RESTORED Historic Office & Restaurant Space NOVEMBER 2022 DELIVERY Adjacent to San Antonio’s Iconic Riverwalk SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS Four-story historic office building containing 26,874 SF Three upper floors of office space, ground level restaurant / bar space Surrounded by government offices, hotels, restaurants and mixed-use residential 39 million people visit San Antonio annually and the Riverwalk is Texas’ number one tourist attraction. 100 Years of100 Years Riverwalk History - Beautifully Restored SAN ANTONIO CITY HALL SAN FERNANDO CATHEDRAL PLAZA DE LAS ISLAS CANARIAS S FLORES ST CADENA REEVES MARKET STREET JUSTICE CENTER BEXAR COUNTY COURTHOUSE MAIN PLAZA DIRECTLY ACROSS FROM COMMERCE STREET BEXAR COUNTY COURTHOUSE WITHIN BLOCKS OF MANY FEDERAL, COUNTY AND CITY GOVERNMENT OFFICES ONE BLOCK FROM MARKET STREET WALKING DISTANCE TO NUMEROUS HOTELS AND RESTAURANTS MAIN PLAZA AMPLE PARKING RESTAURANT AND OFFICE VIEWS OVERLOOKING RIVERWALK VILLITA STREET PRIME SAN ANTONIO RIVERWALK LOCATION Tower Life Building Drury Plaza Cadena Reeves Hotel Justice Center Bexar County Granada Courthouse Riverwalk Plaza Homes Hotel Main Plaza E Nueva St Tower of the Americas Tower Life Hemisfair Building Park Alamodome IMAX Theatre Henry B. Gonzalez The Alamo Convention Center 200 MAIN PLAZA WYNDHAM RIVERWALK E Pecan St WESTON P CENTRE THE CHILDREN’S P HOSPITAL OF SAN ANTONIO N SANTA ROSA INT’L BANK OF P COMMERCE EMBASSY SHERATON SUITES GUNTER HOUSTON ST HOTEL MAJESTIC VALENCIA EMPIRE THEATRE MILAM PARK THEATRE HOME 2 HOLIDAY P SUITES INN MARRIOTT -

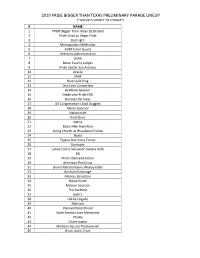

2019 Pride Bigger Than Texas Preliminary Parade Lineup

2019 PRIDE BIGGER THAN TEXAS PRELIMINARY PARADE LINEUP (*LINEUP IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE*) # NAME 1 PRIDE Bigger Than Texas 2019 Lead 2 Pride Viva Las Vegas Float 3 Bud Light 4 Metropolitan Methodist 5 AVER Color Guard 6 Veterans Administration 7 USAA 8 Bexar County Judges 9 Pride Center San Antonio 10 Oracle 11 SAAF 12 Riverwalk King 13 One Love Counseling 14 Rainbow Sponsor 15 Medtronic Pride ERG 16 Donate Life Texas 17 US Congressman Lloyd Doggett 18 Alamo Sponsor 19 Nationwide 20 Kind Clinic 21 Aetna 22 Booz Allen Hamilton 23 Living Church at Woodlawn Pointe 24 Hyatt 25 Tejano Star Patsy Torres 26 Univision 27 Latina Comic Sensation Sandra Valls 28 BD 29 Moms Demand Action 30 American Red Cross 31 Grand Marshal Gene Wesley Elder 32 Bonham Exchange 33 Alliance Bernstein 34 Fiesta Youth 35 Mission Sponsor 36 The Hartford 37 Kohl’s 38 LULAC Orgullo 39 Marriott 40 Planned Parenthood 41 State Senator Jose Menendez 42 PFLAG 43 Cheer Austin 44 Madison Square Presbyterian 45 Brian Justin Crum 2019 PRIDE BIGGER THAN TEXAS PRELIMINARY PARADE LINEUP (*LINEUP IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE*) 46 SA Street Krewe 47 State Representative Diego Bernal 48 Paseo Sponsor 49 Nordstrom 50 Babios 51 Capital Group 52 Cricket 53 Wells Fargo 54 Luby’s 55 Smirnoff 56 Magnolia Medical 57 Bexar County District Attorney 58 Hemisfair Sponsor 59 Bank of America 60 Favor 61 District Judge Rosie Alvarado 62 Sizzy Rocket 63 800 Live 64 Lez Ride 65 Pride of San Antonio Showband 66 Temple Beth-El 67 University Health 68 Marathon 69 Gold’s Gym 70 La Villita Sponsor 71 Thrive 72 Tennis -

San Antonio, Texas

Volume 1999 Article 10 1999 Archaeological Survey and Testing in San Pedro Park (41BX19), San Antonio, Texas Brett A. Houk Department of Anthropology, Texas Tech University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Cite this Record Houk, Brett A. (1999) "Archaeological Survey and Testing in San Pedro Park (41BX19), San Antonio, Texas," Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 1999, Article 10. https://doi.org/10.21112/ita.1999.1.10 ISSN: 2475-9333 Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol1999/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Regional Heritage Research at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Archaeological Survey and Testing in San Pedro Park (41BX19), San Antonio, Texas Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License This article is available in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol1999/iss1/10 Archaeological Survey and Testing in San Pedro Park (41BX19), San Antonio, Texas Brett A. -

2007 Unified Planning Work Program San Antonio-Bexar County Metropolitan Planning Organization

FY 2006 – 2007 UNIFIED PLANNING WORK PROGRAM SAN ANTONIO-BEXAR COUNTY METROPOLITAN PLANNING ORGANIZATION Adoption by Policy Board: July 25, 2005 Amended by Policy Board: September 30, 2005 Amended by Policy Board: October 24, 2005 Amended by Policy Board: December 5, 2005 Amended by Policy Board: January 23, 2006 Amended by Policy Board: February 27, 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................5 History and Background ............................................................................................................................5 A. Purpose ......................................................................................................................................................6 B. Definition of Area.......................................................................................................................................6 C. Organization...............................................................................................................................................6 Policy Organization....................................................................................................................................7 Technical Organization..............................................................................................................................7 Other Advisory Committees.......................................................................................................................8 -

Hispanic Texans

texas historical commission Hispanic texans Journey from e mpire to Democracy a GuiDe for h eritaGe travelers Hispanic, spanisH, spanisH american, mexican, mexican american, mexicano, Latino, Chicano, tejano— all have been valid terms for Texans who traced their roots to the Iberian Peninsula or Mexico. In the last 50 years, cultural identity has become even more complicated. The arrival of Cubans in the early 1960s, Puerto Ricans in the 1970s, and Central Americans in the 1980s has made for increasing diversity of the state’s Hispanic, or Latino, population. However, the Mexican branch of the Hispanic family, combining Native, European, and African elements, has left the deepest imprint on the Lone Star State. The state’s name—pronounced Tay-hahs in Spanish— derives from the old Spanish spelling of a Caddo word for friend. Since the state was named Tejas by the Spaniards, it’s not surprising that many of its most important geographic features and locations also have Spanish names. Major Texas waterways from the Sabine River to the Rio Grande were named, or renamed, by Spanish explorers and Franciscan missionaries. Although the story of Texas stretches back millennia into prehistory, its history begins with the arrival of Spanish in the last 50 years, conquistadors in the early 16th cultural identity century. Cabeza de Vaca and his has become even companions in the 1520s and more complicated. 1530s were followed by the expeditions of Coronado and De Soto in the early 1540s. In 1598, Juan de Oñate, on his way to conquer the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico, crossed the Rio Grande in the El Paso area.