Albuquerque Tricentennial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salinas Pueblo Missions NM: Architectural History

Salinas Pueblo Missions NM: Architectural History SALINAS "In the Midst of a Loneliness": The Architectural History of the Salinas Missions "In the Midst of a Loneliness" The Architectural History of the Salinas Missions Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument Historic Structures Report James E. Ivey 1988 Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 15 Southwest Regional Office National Park Service Santa Fe, New Mexico TABLE OF CONTENTS sapu/hsr/hsr.htm Last Updated: 03-Sep-2001 file:///C|/Web/SAPU/hsr/hsr.htm [9/7/2007 2:07:46 PM] Salinas Pueblo Missions NM: Architectural History (Table of Contents) SALINAS "In the Midst of a Loneliness": The Architectural History of the Salinas Missions TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Figures Executive Summary Foreword Acknowledgements Chapter 1: Administrative Background Chapter 2: The Setting of the Salinas Pueblos Chapter 3: An Introduction to Spanish Colonial Construction Method Chapter 4: Abó: The Construction of San Gregorio Chapter 5: Quarai: The Construction of Purísima Concepción Chapter 6: Las Humanas: San Isidro and San Buenaventura Chapter 7: Daily Life in the Salinas Missions Chapter 8: The Salinas Pueblos Abandoned and Reoccupied Chapter 9: The Return to the Salinas Missions file:///C|/Web/SAPU/hsr/hsrt.htm (1 of 6) [9/7/2007 2:07:47 PM] Salinas Pueblo Missions NM: Architectural History (Table of Contents) Chapter 10: Archeology at the Salinas Missions Chapter 11: The Stabilization of the Salinas Missions Chapter 12: Recommendations Notes Bibliography Index (omitted from on-line -

PACIFIC Agency Directory.Indd.Indd

PACIFIC Project Bureau of Justice Assistance U.S. Department of Justice Planning Alternatives & Correctional Institutions For Indian Country PACIFIC Advisory Committee Agency Directory September 2010 Northern Cheyenne Youth Services Center Bureau of Justice Assistance James H. Burch, II, Acting Director Andrew Molloy, Associate Deputy Director Gary Dennis, Senior Policy Advisor Julius Dupree, Policy Advisor 810 Seventh Street, NW Washington, DC 20531 Phone (202) 616-6500 Fax (202) 305-1367 Prepared under Grant No. 2008-IP-BX-K001 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance to Justice Solutions Group, Shelley Zavlek, President. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a com- ponent of the Offi ce of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Offi ce of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, and the Offi ce for Victims of Crime. Table of Contents PACIFIC Advisory Committ ee Members ..............................................................................ii PACIFIC Project Advisory Committ ee Overview.................................................................. 1 Directory of Technical Assistance Providers ....................................................................... 3 Department of Health and Human Services Indian Health Service (IHS) ............................................................................................4 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administrati on (SAMHSA) ....................5 Department of Housing and Urban Development -

Checklist of New Mexico Publications

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 26 Number 2 Article 5 4-1-1951 Checklist of New Mexico Publications Wilma Loy Shelton Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Shelton, Wilma Loy. "Checklist of New Mexico Publications." New Mexico Historical Review 26, 2 (1951). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol26/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. CHECKLIST OF NEW MEXICO PUBLICATIONS By WILMA LOY SHELTON ' (Continued) Messages of the governor to the Territorial and State legis- ' latures, 1847-1949. 1847 Governor's message (Donaciano Vigil) delivered to the Senate and House of Representatives, Santa Fe, N. M., Dec. 6, 1847. '..'Hovey & Davies, Printers. ' First official document 'of its character following the Ameri can occupation. Broadside 24x40.5 em. Text printed in three columns. 1851 Message of His Excellency James S. Calhoun to the First terri toriallegislature of N. M., June 2d, 1851. (Santa Fe) 1851. 7,7p. (E&S) Message of His Excellency James S. Calhoun to the First Terri torial legislature of New Mexico, Dec. 1, 1851. Santa Fe, Printed by J. 'L. Collins and W. G. Kephard, 1851. '8, 8p. (E&S) , , ' 1852 Message of William Carr Lane, Governor of the Territory of N. M., to the Legislative assembly of the territory; at Santa Fe, Dec. 7, 1852. -

Two New Mexican Lives Through the Nineteenth Century

Hannigan 1 “Overrun All This Country…” Two New Mexican Lives Through the Nineteenth Century “José Francisco Chavez.” Library of Congress website, “General Nicolás Pino.” Photograph published in Ralph Emerson Twitchell, The History of the Military July 15 2010, https://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/congress/chaves.html Occupation of the Territory of New Mexico, 1909. accessed March 16, 2018. Isabel Hannigan Candidate for Honors in History at Oberlin College Advisor: Professor Tamika Nunley April 20, 2018 Hannigan 2 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 2 I. “A populace of soldiers”, 1819 - 1848. ............................................................................................... 10 II. “May the old laws remain in force”, 1848-1860. ............................................................................... 22 III. “[New Mexico] desires to be left alone,” 1860-1862. ...................................................................... 31 IV. “Fighting with the ancient enemy,” 1862-1865. ............................................................................... 53 V. “The utmost efforts…[to] stamp me as anti-American,” 1865 - 1904. ............................................. 59 Conclusion .............................................................................................................................................. 72 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ -

GAME NOTES Tuesday, May 11, 2021

GAME NOTES Tuesday, May 11, 2021 2019 PCL Pacific Southern Division Champions Game 6 – Home Game 6 Sacramento River Cats (2-3) (AAA-S.F. Giants) vs. Las Vegas Reyes de Plata (3-2) (AAA-Oakland Athletics) Aviators At A Glance . The Series (L.V. leads 3-2) Overall Record: 3-2 (.600) Home: 3-2 (.600) PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS Road: 0-0 (.000) Day Games: 1-0 (1.000) SACRAMENTO LAS VEGAS Tues. (7:05) – LHP Anthony Banda (1-0, 0.00) RHP Matt Milburn 0-0, 0.00) Night Games: 2-2 (.500) Wednesday, May 12 OFF DAY Follow the Aviators on Facebook/Las Vegas Aviators Baseball Team & Twitter/@AviatorsLV Probable Starting Pitchers (Las Vegas at Reno, May 13-18) RENO LAS VEGAS Thurs. (6:35) – TBA RHP Parker Dunshee (0-1, 13.50) Radio: KRLV AM 920 - Russ Langer Fri. (6:35) – TBA RHP Grant Holmes (0-0, 15.00) Web & TV: www.aviatorslv.com; MiLB.TV Sat. (4:05) – TBA RHP Paul Blackburn (0-0. 5.40) Aviators vs. River Cats: The Las Vegas Reyes de Plata professional baseball team, Triple-A affiliate of the Oakland Athletics, will host the Sacramento River Cats, Triple-A affiliate of the San Francisco Giants, tonight in the finale of the season -opening six-game series in Triple-A West action at Las Vegas Ballpark (8,834)…Las Vegas is 3-2 on the homestand…following an off day on Wednesday, May 12, Las Vegas will embark on its first road trip of the season to Northern Nevada to face intrastate rival, the Reno Aces, Triple-A affiliate of the Arizona Diamondbacks, in a six-game series at Greater Nevada Field from Thursday-Tuesday, May 13-18. -

FROM BULLDOGS to SUN DEVILS the EARLY YEARS ASU BASEBALL 1907-1958 Year ...Record

THE TRADITION CONTINUES ASUBASEBALL 2005 2005 SUN DEVIL BASEBALL 2 There comes a time in a little boy’s life when baseball is introduced to him. Thus begins the long journey for those meant to play the game at a higher level, for those who love the game so much they strive to be a part of its history. Sun Devil Baseball! NCAA NATIONAL CHAMPIONS: 1965, 1967, 1969, 1977, 1981 2005 SUN DEVIL BASEBALL 3 ASU AND THE GOLDEN SPIKES AWARD > For the past 26 years, USA Baseball has honored the top amateur baseball player in the country with the Golden Spikes Award. (See winners box.) The award is presented each year to the player who exhibits exceptional athletic ability and exemplary sportsmanship. Past winners of this prestigious award include current Major League Baseball stars J. D. Drew, Pat Burrell, Jason Varitek, Jason Jennings and Mark Prior. > Arizona State’s Bob Horner won the inaugural award in 1978 after hitting .412 with 20 doubles and 25 RBI. Oddibe McDowell (1984) and Mike Kelly (1991) also won the award. > Dustin Pedroia was named one of five finalists for the 2004 Golden Spikes Award. He became the seventh all-time final- ist from ASU, including Horner (1978), McDowell (1984), Kelly (1990), Kelly (1991), Paul Lo Duca (1993) and Jacob Cruz (1994). ODDIBE MCDOWELL > With three Golden Spikes winners, ASU ranks tied for first with Florida State and Cal State Fullerton as the schools with the most players to have earned college baseball’s top honor. BOB HORNER GOLDEN SPIKES AWARD WINNERS 2004 Jered Weaver Long Beach State 2003 Rickie Weeks Southern 2002 Khalil Greene Clemson 2001 Mark Prior Southern California 2000 Kip Bouknight South Carolina 1999 Jason Jennings Baylor 1998 Pat Burrell Miami 1997 J.D. -

Pojoaque Valley Schools Social Studies CCSS Pacing Guide 7 Grade

Pojoaque Valley Schools Social Studies CCSS Pacing Guide 7th Grade *Skills adapted from Kentucky Department of Education ** Evidence of attainment/assessment, Vocabulary, Knowledge, Skills and Essential Elements adapted from Wisconsin Department of Education and Standards Insights Computer-Based Program Version 2 2016- 2017 ADVANCED CURRICULUM – 7th GRADE (Social Studies with ELA CCSS and NGSS) Version 2 1 Pojoaque Valley Schools Social Studies Common Core Pacing Guide Introduction The Pojoaque Valley Schools pacing guide documents are intended to guide teachers’ use of New Mexico Adopted Social Studies Standards over the course of an instructional school year. The guides identify the focus standards by quarter. Teachers should understand that the focus standards emphasize deep instruction for that timeframe. However, because a certain quarter does not address specific standards, it should be understood that previously taught standards should be reinforced while working on the focus standards for any designated quarter. Some standards will recur across all quarters due to their importance and need to be addressed on an ongoing basis. The Standards are not intended to be a check-list of knowledge and skills but should be used as an integrated model of literacy instruction to meet end of year expectations. The Social Studies CCSS pacing guides contain the following elements: • Strand: Identify the type of standard • Standard Band: Identify the sub-category of a set of standards. • Benchmark: Identify the grade level of the intended standards • Grade Specific Standard: Each grade-specific standard (as these standards are collectively referred to) corresponds to the same-numbered CCR anchor standard. Put another way, each CCR anchor standard has an accompanying grade-specific standard translating the broader CCR statement into grade- appropriate end-of-year expectations. -

Crescent Real Estate Equities Ltd Partnership

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 10-Q Quarterly report pursuant to sections 13 or 15(d) Filing Date: 1999-05-17 | Period of Report: 1999-03-31 SEC Accession No. 0000950134-99-004411 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER CRESCENT REAL ESTATE EQUITIES LTD PARTNERSHIP Mailing Address Business Address 777 MAIN STREET SUITE 2100777 MAIN STREET CIK:1010958| IRS No.: 752531304 | State of Incorp.:DE 777 MAIN STREET SUITE 2100SUITE 2100 Type: 10-Q | Act: 34 | File No.: 333-42293 | Film No.: 99627701 FORT WORTH TX 76102 FORT WORTH TX 76102 SIC: 6510 Real estate operators (no developers) & lessors 8178770477 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document 1 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-Q QUARTERLY REPORT UNDER SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR QUARTER ENDED MARCH 31, 1999 COMMISSION FILE NO 1-13038 CRESCENT REAL ESTATE EQUITIES LIMITED PARTNERSHIP ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) TEXAS 75-2531304 ------------------------------- --------------------------------------- (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Identification Number) incorporation or organization) 777 Main Street, Suite 2100, Fort Worth, Texas 76102 -------------------------------------------------------------------- (Address of principal executive offices)(Zip code) Registrant's telephone number, including area code -

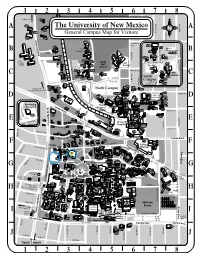

UNM Campus Map.Pdf

12345678 to Bldg. 259 277 Girard Blvd. Princeton Dr. A 278 The University of New Mexico A 255 N 278A General Campus Map for Visitors Vassar Dr. 271 265 University Blvd. 260 Constitution Ave. 339 217 332 Married Casa University Blvd. Student Housing B Esperanza Stanford Dr. 333 B KNME-TV 317-329 270 262 337 218 334 331 Buena Vista Dr. Carrie 240 243 Tingley 272 North Law Avenida De Cesar Chavez Golf 301 Hospital 233 241 239 School “The Pit” Camino de Salud Course 302 237 236B 230 Mountain Rd. 312 307 C 223 Stanford Dr. UNM C 206 Stadium 205 242 Columbia Dr. South 308 238 236A Campus 311 Tucker Rd. Tucker Rd. to South Golf Course 311A C 216 a 276 m 208 210 221 to Bldg. 259 252 in North Campus 219 o 263 1634 University Blvd. NE d e 251 S a 213-215 209 231 Marble Ave. lu Yale Blvd. Bernalillo Cty. D 250 d 249 D Mental Health 246 273 204 248 234 266 Center 225 268 258 Continuing Health 228 U 253 247 n Education Lomas Blvd. i Sciences 229 v 211 e 226 r Center 212 s 264 Frontier Ave. i t y 220 201 B l v 203 d 259 183 . 227 232 Girard Blvd. E N. Yale Entrance E 175 202 Vassar Dr. Mesa Vista Rd. 207 University Indian School Rd. Hospital University Blvd. University Mesa Vista Rd. 235 Revere Pl. 182 224 Sigma Chi Rd. 165 154 256 269 171 Spruce St. 191 151 Si d. Yale Blvd. -

New Mexico Lobo, Volume 044, No 36, 2/6/1942 University of New Mexico

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository 1942 The aiD ly Lobo 1941 - 1950 2-6-1942 New Mexico Lobo, Volume 044, No 36, 2/6/1942 University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/daily_lobo_1942 Recommended Citation University of New Mexico. "New Mexico Lobo, Volume 044, No 36, 2/6/1942." 44, 36 (1942). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ daily_lobo_1942/8 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The aiD ly Lobo 1941 - 1950 at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1942 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~·· i -,~------------------------------~------~(~~--~--~~~ J UNIVERSITY OF N£W M~XICO UBR\RV Page Four ~EW MEXICO LOBO Tuesday, February 3, 1942 • • • The Time Is Being Used Now. • • Student Opinion Vero~ica and Camelia Conspire, • By GWENN PERRY During the past two weeks the LOBO has dition of responsibility will feel in times of for this "stalemate"·has been obvious. Lobo Poll Editor mal'ntained a strictly opinionated attitude inaugural. The LOBO, like other newspapers striv- Question: What policy should the ticket committee follow In regard to admittances to the Junior.. Sen,ior Prom this year? Should it be kept toward its campaign for cheaper prices on Now, a new "strategy" of facts is needed. ing for improvement and reform, must traditional for upperclassmen? What effect do you think admitting on- Perspire in Readiness for Debut school materials here on the campus. -

MEDIA GUIDE 2019 Triple-A Affiliate of the Seattle Mariners

MEDIA GUIDE 2019 Triple-A Affiliate of the Seattle Mariners TACOMA RAINIERS BASEBALL tacomarainiers.com CHENEY STADIUM /TacomaRainiers 2502 S. Tyler Street Tacoma, WA 98405 @RainiersLand Phone: 253.752.7707 tacomarainiers Fax: 253.752.7135 2019 TACOMA RAINIERS MEDIA GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Front Office/Contact Info .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Cheney Stadium .....................................................................................................................................................6-9 Coaching Staff ....................................................................................................................................................10-14 2019 Tacoma Rainiers Players ...........................................................................................................................15-76 2018 Season Review ........................................................................................................................................77-106 League Leaders and Final Standings .........................................................................................................78-79 Team Batting/Pitching/Fielding Summary ..................................................................................................80-81 Monthly Batting/Pitching Totals ..................................................................................................................82-85 Situational -

DRAFT East Downtown/Huning Highlands/South Martineztown Metropolitan Redevelopment Area Designation Report

Metropolitan Redevelopment Agency Staff Report Case Number: 2019-003 Applicant: Metropolitan Redevelopment Agency Request(s): Major Expansion of the Old Albuquerque High School Metropolitan Redevelopment Area and Renaming the Area to the East Downtown/Huning Highlands/South Martineztown Metropolitan Redevelopment Area. BACKGROUND Metropolitan Redevelopment Agency staff are proposing a major expansion of the Old Albuquerque High Metropolitan Redevelopment Area to include the commercial corridor along Central and Martin Luther King Jr between Broadway and I-25 and the east side of Broadway from Lomas to Coal Ave. The new area will be renamed the East Downtown/Huning Highlands/South Martineztown/Metropolitan Redevelopment Area. Please find the attached Redevelopment Area Designation Report. FINDINGS 1. Throughout the proposed area there are a number of aging and deteriorating buildings and structures that are in need of repair, rehabilitation and in some instances removal. 2. A significant number of commercial or mercantile businesses have closed. 3. Throughout the proposed area there exists a deterioration of site improvements. 4. There exists low levels of commercial or industrial activity or redevelopment. 5. The existing conditions within the proposed East Downtown/Huning Highlands/South Martineztown Metropolitan Redevelopment Area sufficiently meet the definition of “Blight” as required by the MR Code ((§ 3-60A8), NMSA 1978). “…because of the presence of a substantial number of deteriorated or deteriorating structures…deterioration