F EE AA SS Ii Bb Ii Ll Ii Tt YY Financial Economic Analysis Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guía Para El Uso De Canales Electrónicos. Canal Cajeros Automáticos

GUIA PARA EL USO DE CANALES ELECTRONICOS CAJEROS AUTOMÁTICOS –ATM– INGENIERÍA DE PROCESOS INDICE INTRODUCCIÓN...........................................................................................................................................................3 1. CAJEROS AUTOMÁTICOS (ATM ) .............................................................................................................................5 1.1. Características y beneficios principales ............................................................................................................5 1.2. Operaciones Disponibles ...................................................................................................................................5 1.2.1. Extracción / Adelanto ..................................................................................................................................5 1.2.2. Link Pagos .....................................................................................................................................................5 1.2.3. Compras y Recargas .....................................................................................................................................5 1.2.4. Transferencias ..............................................................................................................................................5 1.2.5. Depósitos .....................................................................................................................................................5 -

China Insurance Sector

China / Hong Kong Industry Focus China Insurance Sector Refer to important disclosures at the end of this report DBS Group Research . Equity 1 Nov 2017 Multi-year value growth ahead HSI: 28,336 • Strong growth potential back by C-ROSS, favourable policy direction, and structural drivers ANALYST • Favourable asset/liability mismatch position Ken SHIH +852 2820 4920 [email protected] bodes well under a rising rate environment; China lifers’ book value is set to rise Keith TSANG CFA, +852 2971 1935 nd [email protected] • Impact from 2 phase of auto insurance pricing reform expected to be more severe; online insurers considered to be a disruptive force Recommendation & valuation • Initiating coverage on China Insurance sector. Top picks: China Taiping (966 HK), CPIC (2601 HK), and C losing Targe t FY17F Ping An (2318 HK). Top SELLs: PICC P&C (2328 HK), Stock Ticker Rating Price Price PB Yield ROE and China Re (1508 HK) (HKD) (HK D) (X) (%) (% ) Spotlight on value enhancement: We believe China’s low Ping A n - H 2318 H K BUY 68. 1 86. 0 2.4 1.5 17.8 insurance coverage, launch of China Risk-Oriented Solvency C hina Life - H 2628 H K BUY 25. 8 32. 0 1.9 1.8 9.6 System (C-ROSS), and policy guidance will continue to direct China Taiping 966 HK BUY 25.1 38.0 1.4 1.1 8.9 China life insurers to refocus on traditional life products and C hina Pacific - H 2601 HK BUY 37. 7 54. 0 2.0 2.8 11.1 value enhancement. -

Assessment and Review of Application of Responsibilities for Authorities

Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures Board of the International Organization of Securities Commissions Assessment and review of application of Responsibilities for authorities November 2015 This publication is available on the BIS website (www.bis.org) and the IOSCO website (www.iosco.org). © Bank for International Settlements and International Organization of Securities Commissions 2015. All rights reserved. Brief excerpts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is stated. ISBN 978-92-9197-376-7 (online) Contents 1. Executive summary ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Methodology ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Key findings of the assessment ........................................................................................................................ 2 2. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Broader context of the Responsibilities assessment ............................................................................... 4 2.2 Scope and objective of the Responsibilities assessment ....................................................................... 5 3. Methodology ................................................................................................................................................................... -

CUGN Academic Catalog Contains Current Information Regarding the Academic Calendar, Admissions, Degree Requirements, Fees, Regulations, and Course Offerings

2012 ACADEMIC CATALOG CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY GLOBALNET 2013-14 ACADEMIC CATALOG www.cugn.org Table of Contents Introduction . 3 Academic Policies . .60 Welcome . 4 Drop/Add Procedures . 60 From the President . .. 4 Appeals Process . 60 From the Academic Dean . 5 Honesty/Cheating/Plagiarism . 61 Contacting Us . 6 Student IDs . 61 About CUGN . 7 Bible Competency Exam and Advanced Placement . 61 History . 7 Repeating a Course . 62 Academic Programs . 7 GPA Scale . .. 62 What We Believe . 8 Pass-Fail and Course Validation in Core 1 . 62 Endorsements and Testimonials . 9 Special Student Needs/Accommodations . 63 General Endorsements . 9 CUGN Email Account/Google Docs . 63 Faculty Endorsements . 10 Incompletes . 63 Mission and Vision . .11 Extensions . 63 Academic Calendar / Enrollment Deadlines . 12 Academic Probation . 64 2013 . 12 Dismissal . .. 64 2014 . 13 Transfer Credit . 64 2015 . 14 Part-time, Full-time, Noncredit Students . 65 Curriculum Description . .15 Discussion Forum Guidelines . 65 Summary Chart of Program Requirements . 16 Requirements for Success . 66 M.A.R. Thesis-Project . 19 Tutorials and Learning Management System (LMS) . 66 M.A.R. Concentrations . .20 Bible Competency Exam . 66 Choosing Your M .A .R . Concentration . 20 English Proficiency . 66 Master of Arts in Ministry Studies (accredited) . 23 Computer/Internet/Software Requirements . 66 Certificate Programs . 24 Student Records . 67 Transfer Credit Courses . 26 Mentor Requirements . 67 Course Lists Per Semester . 27 Graduation Procedures . .67 Undergraduate Degree Options . 30 Online Library / Resources . 67 Course Descriptions . 32 Tuition and Financial Aid . 68 Old Testament . 33 Tuition Costs . 68 New Testament . 37 Tuition Payments . 68 Systematic Theology . 41 Refunds . 68 Church History . 42 Financial Assistance . -

Política De Gerenciamento De Risco De Mercado Do Banco

ITAÚ UNIBANCO HOLDING S.A. CNPJ 60.872.504/0001-23 Companhia Aberta COMUNICADO AO MERCADO Tecnologia Bancária S.A. (TECBAN) – Novo Acordo de Acionistas Itaú Unibanco Holding S.A. (“Itaú Unibanco”) informa aos seus acionistas e ao mercado em geral que: 1. Determinadas subsidiárias do Itaú Unibanco (Itaú Unibanco S.A., Unibanco Negócios Imobiliários S.A., Banco Itauleasing S.A., Banco Itaucard S.A. e Intrag – Part. Administração e Participações Ltda.), em conjunto com o Grupo Banco do Brasil (por meio do Banco do Brasil e BB Banco de Investimentos S.A.), o Grupo Santander (por meio do Santander S.A. – Serviços Técnicos, Administrativos e de Corretagem de Seguros), o Grupo Bradesco (por meio do Banco Bradesco S.A., Banco Alvorada S.A. e Alvorada Cartões, Crédito, Financiamento e Investimentos S.A.), o Grupo HSBC (por meio do HSBC Bank Brasil S.A. – Banco Múltiplo), o Grupo Caixa (por meio da Caixa Participações S.A.) e o Grupo Citibank (por meio do Citibank N.A. – Filial Brasileira e Banco Citibank S.A.) (todos, em conjunto, denominados “Partes”), com a interveniência e anuência de Tecnologia Bancária S.A. (“TecBan”), Itaú Unibanco, Banco Santander (Brasil) S.A. e Caixa Econômica Federal, assinaram, em 17 de julho de 2014, um novo Acordo de Acionistas da TecBan (“Acordo de Acionistas”), o qual, tão logo entre em vigor, revogará e substituirá o acordo de acionistas vigente. 2. Além das disposições usuais em acordos de acionistas, como regras sobre governança e transferência de ações, o Acordo de Acionistas prevê que, em aproximadamente 4 (quatro) anos contados de sua entrada em vigor, as Partes deverão ter substituído parte de sua rede externa de Terminais de Autoatendimento (“TAA”) pelos TAAs da Rede Banco24Horas, que são e continuarão sendo geridos pela TecBan. -

Relatório Anual De Meios Eletrônicos De Pagamento

Relatório Anual de Meios Eletrônicos de Pagamento Perspectivas e Tendências 2020 Perspectivas e Tendências 2020 e Tendências Perspectivas - Quem decide, está aqui! www.cardmonitor.com.br Relatório Anual de Meios Eletrônicos de Pagamento de Pagamento Eletrônicos Anual de Meios Relatório Estamos vivenciando um momento único no setor de A PUBLICAÇÃO LÍDER meios eletrônicos de pagamento. As transformações são intensas e cada vez mais rápidas. Ninguém sabe prever DO MERCADO DE MEIOS com precisão os próximos 2 ou 3 anos, mas temos a ELETRÔNICOS DE PAGAMENTO certeza de que nada será como antes. Players ineficien- tes e lentos perderão mercado para os mais ágeis que propuserem soluções inovadoras a partir de seus entu- siasmados times de colaboradores. 2020 será um ano de transição, pois muitas medidas relevantes como open banking, pagamentos instantâneos, LGPD e cadastro po- mais de 10 anos de muito sitivo estarão em processo de implantação. trabalho e dedicação! Pois bem, este Relatório traz a opinião de respeitados executivos do setor sobre as perspectivas e tendências para os próximos anos. Faz parte de nosso Serviço de Monitoração do Mercado de MEP, que inclui também os Flashes semanais, Relatórios mensais, Market Share trimestrais, Plantões, Análises, etc. Vale a pena você investir seu precioso tempo na leitura integral. As opiniões são muito ricas. Se estiver com tempo limitado, leia primeiro nosso resumo executivo (pgs. 167 a 181). Os depoimentos foram coletados em nosso Fórum de Inteligên- Quem decide, está aqui! cia de Mercado, ocorrido em 28 e 29 de novembro de 2019. Complementamos Cardmonitor lider esse trabalho com depoimentos inéditos coletados por meio de um questionário estruturado em janeiro de 2020. -

Mabuhay Miles Travel Card – Frequently Asked Questions

Mabuhay Miles Travel Card – Frequently Asked Questions 1. Why should I use the Mabuhay Miles Travel Card over other cards? Your Mabuhay Miles Travel Card earns 1 Mile for every Php100 (or its equivalent in foreign currency) spent. It is the only Travel Card that contains a PHP wallet so you can use it both in domestic and international transactions. It is a multi‐currency card that will allow you to spend in the supported local currency without worry of fluctuating exchange rates. By being able to spend using the local currency, it will also allow you to manage your funds better while you travel. Skip the call to your bank when converting your points to Miles. Your Miles will be credited directly to your Mabuhay Miles account, not to your Travel Card account. 2. What’s the difference between the existing Mabuhay Miles Membership Card and this new Mabuhay Miles Travel Card? For Elite, Premiere Elite or Million Miler members, your Mabuhay Miles Membership Card will 1) remain solely as a membership card and 2) will indicate your tier status and benefits. The Travel Card will function as your multi‐currency prepaid card. For Classic members, the Travel Card will serve as both the membership card and the multi‐ currency prepaid card. 3. Where can I use my Mabuhay Miles Travel Card? You can use the currencies in your Travel Card in stores worldwide that accept UnionPay. You can also use your Travel Card to withdraw cash and check your currency balance at BancNet ATMs in the Philippines and international ATMs that accept UnionPay. -

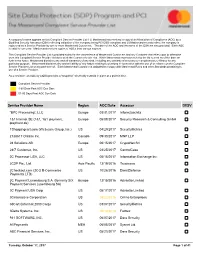

Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV

A company’s name appears on this Compliant Service Provider List if (i) Mastercard has received a copy of an Attestation of Compliance (AOC) by a Qualified Security Assessor (QSA) reflecting validation of the company being PCI DSS compliant and (ii) Mastercard records reflect the company is registered as a Service Provider by one or more Mastercard Customers. The date of the AOC and the name of the QSA are also provided. Each AOC is valid for one year. Mastercard receives copies of AOCs from various sources. This Compliant Service Provider List is provided solely for the convenience of Mastercard Customers and any Customer that relies upon or otherwise uses this Compliant Service Provider list does so at the Customer’s sole risk. While Mastercard endeavors to keep the list current as of the date set forth in the footer, Mastercard disclaims any and all warranties of any kind, including any warranty of accuracy or completeness or fitness for any particular purpose. Mastercard disclaims any and all liability of any nature relating to or arising in connection with the use of or reliance on the Compliant Service Provider List or any part thereof. Each Mastercard Customer is obligated to comply with Mastercard Rules and other Standards pertaining to use of a Service Provider. As a reminder, an AOC by a QSA provides a “snapshot” of security controls in place at a point in time. Compliant Service Provider 1-60 Days Past AOC Due Date 61-90 Days Past AOC Due Date Service Provider Name Region AOC Date Assessor DESV “BPC Processing”, LLC Europe 03/31/2017 Informzaschita 1&1 Internet SE (1&1, 1&1 ipayment, Europe 05/08/2017 Security Research & Consulting GmbH ipayment.de) 1Shoppingcart.com (Web.com Group, lnc.) US 04/29/2017 SecurityMetrics 2138617 Ontario Inc. -

An Empirical Analysis of New Zealand Bank Customers' Satisfaction

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lincoln University Research Archive Lincoln University Digital Thesis Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the thesis and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the thesis. AN EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS OF NEW ZEALAND BANK CUSTOMERS’ SATISFACTION _______________________________________________________ A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Commerce and Management at Lincoln University by Jing Wei _______________________________________________________ Lincoln University 2010 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of M.C.M AN EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS OF NEW ZEALAND BANK CUSTOMERS’ SATISFACTION By Jing Wei It is important that banks deliver quality services which in turn results in customer satisfaction in today’s competitive banking environment. Within the New Zealand financial service market, competition is deemed to be strong given that there have been new entrants into the market as well as mergers and acquisition and exits over the last ten years (Chan, Schumacher, and Tripe, 2007). In order to retain the customers, customer satisfaction becomes a crux issue to bank management. -

The State of Digital Payments in the Philippines (Released in 2015) Found That Adoption Had Been Limited

COUNTRY DIAGNOSTIC The State of Digital Payments in the Philippines DECEMBER 2019 PHILIPPINES Authors Project Leads: Keyzom Ngodup Massally, Rodrigo Mejía Ricart Technical authors: Malavika Bambawale, Swetha Totapally, and Vineet Bhandari Cover photo: © Better Than Cash Alliance/Erwin Nolido 1 FOREWORD Our country was one of the first to pioneer digital payments nearly 20 years ago. Recognizing the untapped market potential and the opportunity to foster greater access to financial inclusion, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) has worked, hand in hand, with the government and the leaders across financial, retail, and regulatory sectors to boost digital payments. Over the past three years, since the launch of the first digital payments diagnostic, the Philippines has experienced remarkable progress toward building an inclusive digital payments ecosystem. In 2013, digital payments accounted for only 1% of the country’s total transaction volume. In 2018, this follow through diagnostic study showed that the volume of digital payments increased to 10% corresponding to 20% share in the total transaction value. These numbers speak of significant progress and success. I am optimistic that e-payments will gain further momentum as we have laid the necessary building blocks to accelerate innovation and inclusive growth over the next few years. Notably, Filipino women are ahead of men in the uptake of digital payments, placing us ahead of global standards. The rise of fintech and their solutions are starting to play a transformative role, as we can see from the rapidly-growing adoption of the emerging QR codes for digital transactions. I am confident that the BSP has built a good digital foundation and is well positioned to leverage fintech in increasing the share of digital payments toward a cash- lite Philippines. -

Chapter 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Globally, banking system is working continuously from many years. Paper money or cash has been leading payment mechanism worldwide for the centuries. The measure works of a bank to deposits an amount of a customer and returns it to him when he needs. During deposits and withdrawal of the amount bank may use this money for itself as to given loans to other customers who wants to avail it. There are so many types of loan like home loan, agricultural loan, personnel loan, loan for industries and business houses etc. Banks give a particular interest for the depositors on his money and take a certain interest from loan account holder. There are very fast changes occur in the traditional banking operation system. Before a decade ago a bank was involved only with customers when they were at premises of bank. But during this new time a bank provides many more services to the customer’s at their doorsteps. The entire system of banking has changed drastically. In banking system there are two most frequent and important services- one is to deposit cash in the account and second to withdraw cash from the account. Both the service provided to a customer during a time in which banks are open and officials present at that time. Here in this work our main concern is about the withdrawal service provided by the bank. Banks normally provide this cash through teller counters. Only in the past century paper money or cash faced competition from mainly cheques, debit and credit cards. Previously this whole process was thoroughly manual and nowadays it is automatic. -

2021 Prime Time for Real-Time Report from ACI Worldwide And

March 2021 Prime Time For Real-Time Contents Welcome 3 Country Insights 8 Foreword by Jeremy Wilmot 3 North America 8 Introduction 3 Asia 12 Methodology 3 Europe 24 Middle East, Africa and South Asia 46 Global Real-Time Pacific 56 Payments Adoption 4 Latin America 60 Thematic Insights 5 Glossary 68 Request to Pay Couples Convenience with the Control that Consumers Demand 5 The Acquiring Outlook 5 The Impact of COVID-19 on Real-Time Payments 6 Payment Networks 6 Consumer Payments Modernization 7 2 Prime Time For Real-Time 2021 Welcome Foreword Spurred by a year of unprecedented disruption, 2020 saw real-time payments grow larger—in terms of both volumes and values—and faster than anyone could have anticipated. Changes to business models and consumer behavior, prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, have compressed many years’ worth of transformation and digitization into the space of several months. More people and more businesses around the world have access to real-time payments in more forms than ever before. Real-time payments have been truly democratized, several years earlier than previously expected. Central infrastructures were already making swift For consumers, low-value real-time payments mean Regardless of whether real-time schemes are initially progress towards this goal before the pandemic immediate funds availability when sending and conceived to cater to consumer or business needs, intervened, having established and enhanced real- receiving money. For merchants or billers, it can mean the global picture is one in which heavily localized use time rails at record pace. But now, in response to instant confirmation, settlement finality and real-time cases are “the last mile” in the journey to successfully COVID’s unique challenges, the pace has increased information about the payment.