Constituting a Self Through an Indian Other. a Study of Select Works by Stefan Zweig and Hermann Hesse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhist” Reading of Shakespeare

UNIWERSYTET ZIELONOGÓRSKI IN GREMIUM 14/2020 Studia nad Historią, Kulturą i Polityką DOI 10.34768/ig.vi14.301 ISSN 1899-2722 s. 193-205 Antonio Salvati Universitá degli Studi della Campania „Luigi Vanvitelli” ORCID: 0000-0002-4982-3409 GIUSEPPE DE LORENZO AND HIS “BUDDHIST” READING OF SHAKESPEARE The road to overcoming pain lies in pain itself The following assumption is one of the pivotal points of Giuseppe De Lorenzo’s reflection on pain: “Solamente l’umanità può attingere dalla visione del dolore la forza per redimersi dal circolo dalla vita”,1 as he wrote in the first edition (1904) of India e Buddhismo antico in affinity with Hölderlin’s verses: “Nah ist/Und schwer zu fassen der Gott./Wo aber Gefahr ist, wächst/Das Rettende auch”,2 and anticipating Giuseppe Rensi who wrote in 1937 in his Frammenti: “La natura dell’universo la conosce non l’uomo sano, ricco, fortunato, felice, ma l’uomo percorso dalle malattie, dalle sventure, dalla povertà, dalle persecuzioni. Solo costui sa veramente che cos’è il mondo. Solo egli lo vede. Solo a lui i dolori che subisce danno la vista”.3 If pain really is this anexperience in which man questions himself and acquires the wisdom to free himself from the state of suffering it is clear why suffering “seems to be particularly essential to the nature of man […] Suffering seems to belong to man’s 1 “Only humanity can draw the strength to redeem itself from the circle of life through the vision of pain”. Giuseppe De Lorenzo (Lagonegro 1871-Naples 1957) was a geologist, a translator of Buddhist texts and Schopenhauer, and a great reader of Shakespeare, Byron and Leopardi. -

Mind-Crafting: Anticipatory Critique of Transhumanist Mind-Uploading in German High Modernist Novels Nathan Jensen Bates a Disse

Mind-Crafting: Anticipatory Critique of Transhumanist Mind-Uploading in German High Modernist Novels Nathan Jensen Bates A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2018 Reading Committee: Richard Block, Chair Sabine Wilke Ellwood Wiggins Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Germanics ©Copyright 2018 Nathan Jensen Bates University of Washington Abstract Mind-Crafting: Anticipatory Critique of Transhumanist Mind-Uploading in German High Modernist Novels Nathan Jensen Bates Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Richard Block Germanics This dissertation explores the question of how German modernist novels anticipate and critique the transhumanist theory of mind-uploading in an attempt to avert binary thinking. German modernist novels simulate the mind and expose the indistinct limits of that simulation. Simulation is understood in this study as defined by Jean Baudrillard in Simulacra and Simulation. The novels discussed in this work include Thomas Mann’s Der Zauberberg; Hermann Broch’s Die Schlafwandler; Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz: Die Geschichte von Franz Biberkopf; and, in the conclusion, Irmgard Keun’s Das Kunstseidene Mädchen is offered as a field of future inquiry. These primary sources disclose at least three aspects of the mind that are resistant to discrete articulation; that is, the uploading or extraction of the mind into a foreign context. A fourth is proposed, but only provisionally, in the conclusion of this work. The aspects resistant to uploading are defined and discussed as situatedness, plurality, and adaptability to ambiguity. Each of these aspects relates to one of the three steps of mind- uploading summarized in Nick Bostrom’s treatment of the subject. -

Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann

Naharaim 2014, 8(2): 210–226 Uri Ganani and Dani Issler The World of Yesterday versus The Turning Point: Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann “A turning point in world history!” I hear people saying. “The right moment, indeed, for an average writer to call our attention to his esteemed literary personality!” I call that healthy irony. On the other hand, however, I wonder if a turning point in world history, upon careful consideration, is not really the moment for everyone to look inward. Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man1 Abstract: This article revisits the world-views of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann by analyzing the diverse ways in which they shaped their literary careers as autobiographers. Particular focus is given to the crises they experienced while composing their respective autobiographical narratives, both published in 1942. Our re-evaluation of their complex discussions on literature and art reveals two distinctive approaches to the relationship between aesthetics and politics, as well as two alternative concepts of authorial autonomy within society. Simulta- neously, we argue that in spite of their different approaches to political involve- ment, both authors shared a basic understanding of art as an enclave of huma- nistic existence at a time of oppressive political circumstances. However, their attitudes toward the autonomy of the artist under fascism differed greatly. This is demonstrated mainly through their contrasting portrayals of Richard Strauss, who appears in both autobiographies as an emblematic genius composer. DOI 10.1515/naha-2014-0010 1 Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man, trans. -

Ut Pictora Poesis Hermann Hesse As a Poet and Painter

© HHP & C.I.Schneider, 1998 Posted 5/22/98 GG Ut Pictora Poesis Hermann Hesse as a Poet and Painter by Christian Immo Schneider Central Washington University Ellensburg, WA, U.S.A. Hermann Hesse stands in the international tradition of writers who are capable of expressing themselves in several arts. To be sure, he became famous first of all for his lyrical poetry and prose. How- ever, his thought and language is thoroughly permeated from his ear- liest to his last works with a profound sense of music. Great art- ists possess the specific gift of shifting their creative power from one to another medium. Therefore, it seems to be quite natural that Hesse, when he had reached a stage in his self-development which ne- cessitated both revitalization and enrichment of the art in which he had thus excelled, turned to painting as a means of the self expres- sion he had not yet experienced. "… one day I discovered an entirely new joy. Suddenly, at the age of forty, I began to paint. Not that I considered myself a painter or intended to become one. But painting is marvelous; it makes you happier and more patient. Af- terwards you do not have black fingers as with writing, but red and blue ones." (I,56) When Hesse began painting around 1917, he stood on the threshold of his most prolific period of creativity. This commenced with Demian and continued for more than a decade with such literary masterpieces as Klein und Wagner, Siddhartha, Kurgast up to Der Steppenwolf and beyond. -

Directions in Contemporary Literature CONTENTS to the Reader Ix PHILO M

Directions in Contemporary Literature CONTENTS To The Reader ix PHILO M. JR. BUCK 1. Introduction Fear 3 2. The Sacrifice for Beauty George Santayana 15 Professor of Comparative Literature, University of Wisconsin 3. A Return to Nature Gerhart Hauptmann 37 4. The Eternal Adolescent André Gide 59 OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS · New York 5. Futility in Masquerade Luigi Pirandello 79 6. The Waters Under the Earth Marcel Proust 101 (iii) 7. The New Tragedy Eugene O'Neill 125 8. The Conscience of India Rabindranath Tagore (vii) 149 COPYRIGHT 1942 BY OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS, 9. Sight to the Blind Aldous Huxley 169 NEW YORK, INC. 10. Go to the Ant Jules Romains 193 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 11. The Idol of the Tribe Mein Kampf 219 12. The Marxian Formula Mikhail Sholokhov 239 (iv) 13. Faith of Our Fathers T. S. Eliot 261 14. The Promise and Blessing Thomas Mann 291 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A WORD must be said of appreciation to those who have aided me in this study. I would name 15. Till Hope Creates Conclusion 315 them, but they are too numerous. There are those who are associated with me in my academic A Suggested Bibliography 337 interests, and those who in one place or another have watched the genesis of the ideas that have Index (viii) 349 gone into these chapters. I must also acknowledge the aid I have received from the current translations of some of the authors, especially Mann and Proust and Sholokhov. In most of the other places the translations are my own. A word about the titles of foreign books: when the English titles are well known I have used them without giving the originals. -

Women As Hidden Authoritarian Figures in Luigi Pirandello's Literary

The Paradox of Identity: Women as Hidden Authoritarian Figures in Luigi Pirandello’s Literary Works Thesis Prospectus by MLA Program Primary Reader: Dr. Susan Willis Secondary Reader: Dr. Mike Winkelman Auburn University at Montgomery 1 December 2010 The Paradox of Identity: 1 Women as Hidden Authoritarian Figures in Luigi Pirandello’s Literary Works On June 28, 1867 in Sicily, Italian author and playwright Luigi Pirandello was born in a town called Caos, translated chaos, during a cholera epidemic. Pirandello’s life was marked by chaos, turmoil, and disease. He literally entered into a world of chaos. Dictated to by a tyrannical father and cared for by a meek mother, Pirandello developed an interesting view of marriage, women, and love. The passivity of his mother and eventual paranoia and insanity of his wife, Antoinette Potulano, created a premise for his literary women. As he formulated and evolved his impressions of the feminine identity from what he witnessed between his parents and experienced with his wife, the “Master of Futurism” examined the flaws of interpersonal communication between genders. He translated those experiences into his literature by depicting institutions such as marriage negatively in his early works and later shifting the bulk of his focus to gender oppositions. Pirandello explores the conundrum between men and women by placing his female characters into paradoxical roles. This thesis challenges previous criticism that maintains Pirandello’s women are “dismembered,” weak, and deconstructed characters and instead concludes that, although Pirandello’s literary women are mutable figures and his literature contains patriarchal elements, a matriarchal society dominates Pirandello’s literature. -

The Theory of the Modern Stage

The Theory of the Modern Stage AN INTRODUCTION TO MODERN THEATRE AND DRAMA EDITED BY ERIC BENTLEY PENGUIN BOOKS Contents Preface by Eric Bentley 9 Acknowledgements 17 PART ONE TEN MAKERS OF MODERN THEATRE ADOLPHE APPIA The Ideas of Adolphe Appia Lee Simonson 27 ANTONIN ARTAUD The Theatre of Cruelty, First and Second Manifestos Antonin Artaud, translated by Mary Caroline Richards 55 Obsessed by Theatre Paul Goodman 76 BERTOLT BRECHT The Street Scene Bertolt Brecht, translated by John Willett 85 On Experimental Theatre Bertolt Brecht, translated by John Willett 97 Helene Weigel: On a Great German Actress and Weigel's Descent into Fame Bertolt Brecht, translated by John Berger and Anna Bostock 105 E. GORDON CRAIG The Art of the Theatre, The First Dialogue E. Gordon Craig 113 A New Art of the Stage Arthur Symans 138 LUIGI PIRANDELLO Spoken Action Luigi Pirandello, translated by Fabrizio Melano 153 Eleanora Duse Luigi Pirandello 158 BERNARD SHAW A Dramatic Realist to His Critics Bernard Shaw 175 Appendix to The Quintessence of Ibsenism Bernard Shaw 197 KONSTANTIN STANISLAVSKY Stanislavsky David Magarshack 219 Emotional Memory Eric Bentley 275 CONTENTS RICHARD WAGNER The Ideas of Richard Wagner Arthur Symons 283 W. B. YEATS A People's Theatre W. B. Yeats 327 A Theory of the Stage Arthur Symons 339 EMILE ZOLA From Naturalism in the Theatre, Emile Zola, translated by Albert Bermel 351 To Begin Otto Brahm, translated by Lee Baxandall 373 PART TWO TOWARDS A HISTORICAL OVER-VIEW GEORG BRANDES Inaugural Lecture, 1871 Georg Brandts, translated by Evert Sprinchorn 383 ARNOLD HAUSER The Origins of Domestic Drama Arnold Hauser, translated in collaboration with the author by Stanley Godman 403 GEORGE LUKACS The Sociology of Modern Drama George Lukdcs, translated by Lee Baxandall 435 ROMAIN ROLLAND From TTie People's Theatre, Romain Rolland, translated by Barrett H. -

P. Vasundhara Rao.Cdr

ORIGINAL ARTICLE ISSN:-2231-5063 Golden Research Thoughts P. Vasundhara Rao Abstract:- Literature reflects the thinking and beliefs of the concerned folk. Some German writers came in contact with Ancient Indian Literature. They were influenced by the Indian Philosophy, especially, Buddhism. German Philosopher Arther Schopenhauer, was very much influenced by the Philosophy of Buddhism. He made the ancient Indian Literature accessible to the German people. Many other authors and philosophers were influenced by Schopenhauer. The famous German Indologist, Friedrich Max Muller has also done a great work, as far as the contact between India and Germany is concerned. He has translated “Sacred Books of the East”. INDIAN PHILOSOPHY IN GERMAN WRITINGS Some other German authors were also influenced by Indian Philosophy, the traces of which can be found in their writings. Paul Deussen was a great scholar of Sanskrit. He wrote “Allgemeine Geschichte der Philosophie (General History of the Philosophy). Friedrich Nieztsche studied works of Schopenhauer in detail. He is one of the first existentialist Philosophers. Karl Eugen Neuman was the first who translated texts from Pali into German. Hermann Hesse was also influenced by Buddhism. His famous novel Siddhartha is set in India. It is about the spiritual journey of a man (Siddhartha) during the time of Gautam Buddha. Indology is today a subject in 13 Universities in Germany. Keywords: Indian Philosophy, Germany, Indology, translation, Buddhism, Upanishads.specialization. www.aygrt.isrj.org INDIAN PHILOSOPHY IN GERMAN WRITINGS INTRODUCTION Learning a new language opens the doors of a different culture, of the philosophy and thinking of that particular society. How true it is in case of Indian philosophy having traveled to Germany years ago. -

Scattered Thoughts on Trauma and Memory*

Scattered thoughts on trauma and memory* ** Paolo Giuganino Abstract. This paper examines, from a personal and clinician's perspective, the interrelation between trauma and memory. The author recalls his autobiographical memories and experiences on this two concepts by linking them to other authors thoughts. On the theme of trauma, the author underlines how the Holocaust- Shoah has been the trauma par excellence of the twentieth century by quoting several writing starting from Rudolf Höss’s memoirs, Nazi lieutenant colonel of Auschwitz, to the same book’s foreword written by Primo Levi, as well as many other authors such as Vasilij Grossman and Amos Oz. The author stresses the distortion of German language operated by Nazism and highlights the role played by the occult, mythological and mystical traditions in structuring the Third Reich,particularly in the SS organization system and pursuit for a pure “Aryan race”. Moreover, the author highlights how Ferenczi's contributions added to the developments of the concept of trauma through Luis Martin-Cabré exploration and detailed study of the author’s psychoanalytic thought. Keywords: Trauma, memory, testimony, Holocaust, Shoah, survivors, state violence, forgiveness, Höss, Primo Levi, Karl Jaspers, Martin Heidegger, Vasilij Grossman, Amos Oz, Ferenczi, Freud, Luis-Martin Cabré. In memory of Gino Giuganino (1913-1949). A mountaineer and partisan from Turin. A righteous of the Italian Jewish community and honoured with a gold medal for having helped many victims of persecution to cross over into Switzerland saving them from certain death. To the Stuck N. 174517, i.e. Primo Levi To: «Paola Pakitz / Cantante de Operetta / Fja de Arone / De el ghetto de Cracovia /Fatta savon / Per ordine del Fuhrer / Morta a Mauthausen» (Carolus L. -

Teaching the Short Story: a Guide to Using Stories from Around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 453 CS 215 435 AUTHOR Neumann, Bonnie H., Ed.; McDonnell, Helen M., Ed. TITLE Teaching the Short Story: A Guide to Using Stories from around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1947-6 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 311p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 19476: $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB 'TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Collected Works General (020) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Higher Education; High Schools; *Literary Criticism; Literary Devices; *Literature Appreciation; Multicultural Education; *Short Stories; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Comparative Literature; *Literature in Translation; Response to Literature ABSTRACT An innovative and practical resource for teachers looking to move beyond English and American works, this book explores 175 highly teachable short stories from nearly 50 countries, highlighting the work of recognized authors from practically every continent, authors such as Chinua Achebe, Anita Desai, Nadine Gordimer, Milan Kundera, Isak Dinesen, Octavio Paz, Jorge Amado, and Yukio Mishima. The stories in the book were selected and annotated by experienced teachers, and include information about the author, a synopsis of the story, and comparisons to frequently anthologized stories and readily available literary and artistic works. Also provided are six practical indexes, including those'that help teachers select short stories by title, country of origin, English-languag- source, comparison by themes, or comparison by literary devices. The final index, the cross-reference index, summarizes all the comparative material cited within the book,with the titles of annotated books appearing in capital letters. -

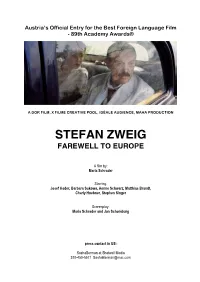

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

Siddhartha's Smile: Schopenhauer, Hesse, Nietzsche

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Fall 2015 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Fall 2015 Siddhartha's Smile: Schopenhauer, Hesse, Nietzsche Benjamin Dillon Schluter Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2015 Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, and the German Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Schluter, Benjamin Dillon, "Siddhartha's Smile: Schopenhauer, Hesse, Nietzsche" (2015). Senior Projects Fall 2015. 42. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2015/42 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Siddhartha’s Smile: Schopenhauer, Hesse, Nietzsche Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies and The Division of Languages and Literature of Bard College by Benjamin Dillon Schluter Annandale-on-Hudson, New York December 2015 Acknowledgments Mom: This work grew out of our conversations and is dedicated to you. Thank you for being the Nietzsche, or at least the Eckhart Tolle, to my ‘Schopenschluter.’ Dad: You footed the bill and never batted an eyelash about it. May this work show you my appreciation, or maybe just that I took it all seriously.