Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

|||GET||| the World of Yesterday 1St Edition

THE WORLD OF YESTERDAY 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Stefan Zweig | 9780803226616 | | | | | [PDF] The World of Yesterday Book by Stefan Zweig Free Download (461 pages) Indriven into exile by the Nazis, he emigrated to England and then, into Brazil by way of New York. Most importantly, each chapter of his The World of Yesterday 1st edition made me appreciate a time and era when books were prominent and intellectual discussion was paramount. As an Autrian-Jewish writer who experienced both World Wars and encountered numerous influencial and interesting people in his life, I expected Zweig would have a facinating story to tell. Everyone collapses with the Sarajevo bombing. Stefan Zweig even claims that the purpose of the school was to discipline and calm the ardor of the youth. Let's try this one more time. There are some very interesting insights in the Hitler chapter, but Zweig soon escaped and lived in relative peace, and so was not the best witness as he admits for the events he subsequently lived through. Our day is gone. Condition: Very Fine. Like his odd friendship with Rathenau, apparently conducted entirely in moving vehicles and the spaces between appointments, watching a powerful mind NOT engaged exclusively with Art but able to understand itnavigate the world. The fact that Zweig and his wife both committed suicide during the war, e I read the first hundred pages or so which painted a vivid picture of life in the waning days of the Hapsburg empire, the patronage of arts, the stability and security felt by everyone, the Jewish community's dynamism, and schooling and university. -

Klaus Mann's Mephisto: a Secret Rivalry

Studies in 20th Century Literature Volume 13 Issue 2 Article 6 8-1-1989 Klaus Mann's Mephisto: A Secret Rivalry Peter T. Hoffer Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the German Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Hoffer, Peter T. (1989) "Klaus Mann's Mephisto: A Secret Rivalry," Studies in 20th Century Literature: Vol. 13: Iss. 2, Article 6. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1234 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Klaus Mann's Mephisto: A Secret Rivalry Abstract Critics of the 1960s and 1970s have focused their attention on Klaus Mann's use of his former brother-in- law, Gustaf Gründgens, as the model for the hero of his controversial novel, Mephisto, while more recent critics have emphasized its significance as a work of anti-Fascist literature. This essay seeks to resolve some of the apparent contradictions in Klaus Mann's motivation for writing Mephisto by viewing the novel primarily in the context of his life and career. Although Mephisto is the only political satire that Klaus Mann wrote, it is consistent with his life-long tendency to use autobiographical material as the basis for much of his plot and characterization. Mann transformed his ambivalent feelings about Gründgens, which long antedated the writing of Mephisto, into a unique work of fiction which simultaneously expresses his indignation over the moral bankruptcy of the Third Reich and reveals his envy of Gründgens's career successes. -

Nostalgia for Fin De Siècle Vienna

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU Experiential Learning & Community Celebrating Scholarship & Creativity Day Engagement 4-24-2014 Much more than longing: Nostalgia for Fin de Siècle Vienna Dana Hicks College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/elce_cscday Part of the European History Commons, and the Intellectual History Commons Recommended Citation Hicks, Dana, "Much more than longing: Nostalgia for Fin de Siècle Vienna" (2014). Celebrating Scholarship & Creativity Day. 28. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/elce_cscday/28 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Celebrating Scholarship & Creativity Day by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Much More Than Longing: Nostalgia for Fin de Siècle Vienna Dana R. Hicks HIST 399: Senior Thesis Dr. Schroeder March 19, 2014 Hicks 2 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Historiography ........................................................................................................................................... 5 A Modern Understanding of Nostalgia ................................................................................................ 11 Sources of Nostalgia -

Stefan Zweig at the End of the World Pdf, Epub, Ebook

STEFAN ZWEIG AT THE END OF THE WORLD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK George Prochnik | 396 pages | 05 Jun 2014 | Other Press LLC | 9781590516126 | English | New York, United States Stefan Zweig at the End of the World PDF Book Other editions. He feels the need to bear witness to the next generation of what his age has gone through, mostly since it has known almost everything due to the better dissemination of information and the total involvement of the populations in the conflicts: wars First World War, Second World War , famines, epidemics, economic crisis, etc. They'd passed through the same faith-obliterating war, and lived with the lingering socioeconomic devastation of that conflict. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Regarding the author's narrative strategy and design. Now I have the context. And of course, when the Nazis blew his favorite venues and stages to little tiny bits and the cheering of adoring, star-struck audiences stopped, Zweig couldn't cope - precisely because there was nothing to him at all except shell and surface. A turning point took place in their fortnight: school no longer satisfied their passion, which shifted to the art of which Vienna was the heart. Zweig thought it prudent not to be present. The reader, too, can feel a bit at sea, or like a guest at a party shuttling down a hectic receiving line. Retrieved 4 May His life was beautiful and it was tragic. Photos I thought were of Zweig's family turn out upon getting to the the photo list at the very end of the book to be from Prochnik's own family. -

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

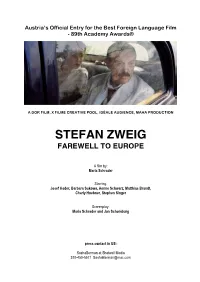

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

The Zweigesque in Wes Anderson's "The Grand Budapest Hotel"

THE ZWEIGESQUE IN WES ANDERSON’S “THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL” Malorie Spencer A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2018 Committee: Edgar Landgraf, Advisor Kristie Foell ii ABSTRACT Edgar Landgraf, Advisor This thesis examines the parallels between narrative structures, including frame narratives and narrative construction of identity, as well as poetic and thematic parallels that exist between the writings of Stefan Zweig and the Wes Anderson film, The Grand Budapest Hotel. These parallels are discussed in order to substantiate Anderson’s claim that The Grand Budapest Hotel is a zweigesque film despite the fact that it is not a direct film adaptation of any one Zweig work. Anderson’s adaptations of zweigesque elements show that Zweig’s writings continue to be relevant today. These adaptations demonstrate the intricate ways in which narrative devices can be used to construct stories and reconstruct history. By drawing on thematic and stylistic elements of Zweig’s writings, Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel raises broader questions about both the necessity of narratives and their shortcomings in the construction of identity; Anderson’s characters both rely on and challenge the ways identity is constructed through narrative. This thesis shows how the zweigesque in Anderson’s film is able to challenge how history is viewed and how people conceptualize and relate to their continually changing notions of identity. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my family for their encouragement throughout the process of writing this thesis. -

Modern Group Portraits in New York Exile Community and Belonging in the Work of Arthur Kaufmann and Hermann Landshoff

Modern Group Portraits in New York Exile Community and Belonging in the Work of Arthur Kaufmann and Hermann Landshoff Burcu Dogramaci In the period 1933–1945 the group portrait was an important genre of art in exile, which has so far received little attention in research.1 Individual works, such as Max Beckmann’s group portrait Les Artistes mit Gemüse, painted in 1943 in exile in Amsterdam,2 were indeed in the focus. Until now, however, there has been no systematic investigation of group portraits in artistic exile during the Nazi era. The following observations are intended as a starting point for further investigations, and concentrate on the exile in New York and the work of the emigrated painter Arthur Kaufmann and photographer Hermann Landshoff in the late 1930s and 1940s, who devoted themselves to the genre of group portraits. 3 New York was a destination that attracted a much larger number of emigrant artists, writers, and intellectuals than other places of exile, such as Istanbul or Shanghai. A total of 70,000 German-speaking emigrants who fled from National Socialism found (temporary) refuge in New York City, including—among many others—the painters Arthur Kaufmann and Lyonel Feininger, and the photographers Hermann Landshoff, Lotte Jacobi, Ellen Auerbach, and Lisette Model.4 Such an accumulation of emigrated artists and photographers in one place may explain the increasing desire to visualize group formats and communal compositions. In the genre of the group picture there are attempts to compensate for the displacement from the place of origin.5 This mode of self-portrayal as a group can be 1/15 found in the photographic New York group portraits where the exiled surrealists had their pictures taken together or with their American colleagues. -

Wir Brauchen Einen Ganz Anderen Mut. Stefan Zweig – Abschied Von Europa 3

Lobkowitzplatz 2, 1010 Wien www.theatermuseum.at JÄNNER 2014 Wir brauchen einen ganz anderen Mut. Stefan Zweig – Abschied von Europa 3. April 2014 bis 12. Jänner 2015 ZUR AUSSTELLUNG Als der österreichische Schriftsteller Stefan Zweig (1881–1942) 1934 nach England und in der Folge nach Brasilien emigrierte, verließ ein überaus erfolgreicher Autor Europa. Dennoch sind es zwei Werke, die Zweig erst im Exil verfasst hat, die heute sein Bild bestimmen. Im Blick auf Die Welt von Gestern und die Schachnovelle entdeckt das Theatermuseum Zweigs Leben und Werk auf neue Weise. Es ist die Perspektive der Vertreibung, die die Ausstellung charakterisiert. Angelpunkt der Gestaltung ist das „Metropol“, das als mondänes Hotel das Fin de siècle ebenso repräsentiert, wie es als Gestapo-Hauptquartier zum Schreckensort schlechthin wurde. PressefOTOS Die Bilder sind für die Berichterstattung über die Ausstellung frei und stehen zum Download bereit unter www.theatermuseum.at/presse/ © Stefan Zweig Centre Salzburg Lobkowitzplatz 2, 1010 Wien www.theatermuseum.at JÄNNER 2014 Trägt die Sprache schon Gesang in sich... Richard Strauss und die Oper 12. Juni 2014 bis 9. Februar 2015 ZUR AUSSTELLUNG Richard Strauss zählt zu den wichtigsten Komponisten der beginnenden Moderne und wurde als Opernkomponist in aller Welt geschätzt. Strauss unterhielt zahlreiche Verbindungen nach Wien, wo er zwischen 1919 und 1924 als Direktor der Wiener Staatsoper große Triumphe, aber auch zahlreiche Niederlagen erlebte. Anlässlich seines 150. Geburtstages präsentiert das Theatermuseum seine umfangreichen Strauss-Bestände, unter ihnen die Korrespondenz mit Hugo von Hofmannsthal sowie den großen Schatz an Bühnenbild- und Kostümentwürfen von Alfred Roller. PressefOTOS Die Bilder sind für die Berichterstattung über die Ausstellung frei und stehen zum Download bereit unter www.theatermuseum.at/presse/ © Theatermuseum. -

A Hero's Work of Peace: Richard Strauss's FRIEDENSTAG

A HERO’S WORK OF PEACE: RICHARD STRAUSS’S FRIEDENSTAG BY RYAN MICHAEL PRENDERGAST THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in Music with a concentration in Musicology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Adviser: Associate Professor Katherine R. Syer ABSTRACT Richard Strauss’s one-act opera Friedenstag (Day of Peace) has received staunch criticism regarding its overt militaristic content and compositional merits. The opera is one of several works that Strauss composed between 1933 and 1945, when the National Socialists were in power in Germany. Owing to Strauss’s formal involvement with the Third Reich, his artistic and political activities during this period have invited much scrutiny. The context of the opera’s premiere in 1938, just as Germany’s aggressive stance in Europe intensified, has encouraged a range of assessments regarding its preoccupation with war and peace. The opera’s defenders read its dramatic and musical components via lenses of pacifism and resistance to Nazi ideology. Others simply dismiss the opera as platitudinous. Eschewing a strict political stance as an interpretive guide, this thesis instead explores the means by which Strauss pursued more ambiguous and multidimensional levels of meaning in the opera. Specifically, I highlight the ways he infused the dramaturgical and musical landscapes of Friedenstag with burlesque elements. These malleable instances of irony open the opera up to a variety of fresh and fascinating interpretations, illustrating how Friedenstag remains a lynchpin for judiciously appraising Strauss’s artistic and political legacy. -

Inhalt. Seilt Geleitwort

Inhalt. Seilt Geleitwort. Von Clara Körben . 3 I. Aus österreichischem Geiste. Aphorismen. Von Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach 9 Der Schleier der Beatrice (Schlußverse). Von Arthur Schnitzler .... 10 Die verwandelte Welt. Von Hans Müller 11 Das Landgut der Fiametta. Von Raoul Auernheimer 13 Lemberg. Von Thaddäus Rittner 22 Die Flöte. Von Franz Karl Ginzkey 23 Die Helfenden. Von Lola Lorme 24 Bischof Dr. Rudolf Hittmair und Enrita von Handel-Mazzetti. Mitgeteilt von Enrika von Handel-Mazzetti (aus der Hittmair-Biographie von Pesendorfer) . 25 Ostermorgen im Felde. Von Mathilde Gräfin Stubenberg 30 Deutsches Wiegenlied. Von Alfons Petzold 30 Dem Hiasl fei Feldpost (steirisch). Von Hermann Kienzl 31 Der Sommer. Von Peter Attenberg 32 Der Frosch. Von Peter Altenberg 32 Deutsche Lehre. Von Hans Fraungruber 33 Die Leute vom blauen Guguckshaus. Von Emil Ertl (aus der Roman- Trilogie „Ein Volk an der Arbeit") 33 Adria-Idyllen. Von Irma von Höfer 45 England und die Kulturphilosophie Bacon-Shakespeares in ihren Beziehungen zum gegenwärtigen Weltkrieg. Von Hofrat Alfred von Weber-Ebenhof 50 St. Michael. Von Gabriele Fürstin Wrede 64 Echt österreichisch. Von Marianne Schrutka von Rechtenstamm ... 65 Zwei Tannen. Don Else Rubricius 66 II. An Österreichs Schwert. Zum 18. August 1915. Von Peter Rosegger 69 Das große Händefalten. Von Anton Wildgans 69 Mein Österreich. Von Richard Schaukal 71 Die Kriegssage vom Untersberg. Von GiselavonBerger 72 Die Glocken kommen. Von Angelika von Hörmann 76 Schwertbrüder. Von Karl Rogner 77 Österreichisches Reiterlied. Von Hugo Iuckermannf . 78 Przemysl. Von Maria Eugenia teile Grazie 79 Weihnachten in Przemysl. Von Herma von Skoda 80 Aus» Osterreich, aus. Von HermavonSkoda 81 5 Bibliografische Informationen digitalisiert durch N/" http://d-nb.info/362276870 31 "HEI1 Seite Mein Bub. -

The Idea of America in Austrian Political Thought 1870-1960

The Idea of America in Austrian Political Thought 1870-1960 David Wile Advisor: Dr. Alan Levine, School of Public Affairs University Honors Spring 2012 Wile 1 Abstract Between 1870 and 1960, the United States of America and Austria experienced two opposite political paths. The United States emerged from the wreckage of the Civil War as a more centralized republic and at the turn of the century became an imperial power, a status that the First and Second World Wars only solidified. Meanwhile, Austria ended the nineteenth century as one of Europe’s largest empires, yet after World War I, all that remained of the intellectual and cultural center of the Habsburg Empire was a tiny remnant cut off from its breadbasket in Hungary, its industrial center in Bohemia, and its seaports in the Balkans. Against the backdrop of a dying empire observing a nascent one, this project examines the discourse through which prominent members of the Austrian, and especially Viennese, intellectual elite imagined the United States of America, and attempts to determine which patterns emerged in that discourse. The Austrian thinkers and writers who are the major focus of this work are: the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, the Zionist Theodor Herzl, the feuilletonist and satirist Karl Kraus, two of the most prominent members of the Austrian School of economics, Ludwig von Mises and F.A. Hayek, and an economist of the Historical School, Joseph Schumpeter. To a lesser extent, the work refers to writers Stefan Zweig, Albert Kubin, and Arthur Schnitzler, philosophers Otto Weininger and Franz Brentano, and two more Austrian School economists, Carl Menger and Friedrich von Wieser. -

Flucht Und Exil Der Familie Mann FREMDE HEIMAT 12

Flucht und Exil der Familie Mann FREMDE HEIMAT 12. Juni 2016 – 8. Januar 2017 Lehrermaterial ALIEN HOMELAND 1 HERZLICH WILLKOMMEN im Lehrermaterial ALIEN HOMELAND zur Sonderausstellung „Fremde Heimat. Flucht und Exil der Familie Mann“ (12. Juni 2016 – 8. Januar 2017, Buddenbrookhaus). ALIEN HOMELAND bietet Ihnen neben vertiefenden Informationen zur Ausstellung auch Anregungen für Ihren Aufenthalt in der Ausstellung und verzahnt damit ihren Unterricht mit unserer Ausstellung. Besonders für das erste Jahr der Qualifikationsphase in der Sekundarstufe II des Deutschunterrichtes geeignet, eröffnet Ihnen und Ihrer Klasse das Lehrermaterial für die Bereiche „Kontinuitäten & Diskontinuitäten“, „Zusammenhang von Sprache – Denken – Wirklichkeit“ sowie „Literarische Themen im Wandel“ (Anpassung & Widerstand, Macht & Gewalt, Recht & Unrecht) eine ganz neue Perspektive. Was macht Exilliteratur zu einer solchen? Welche persönlichen wie kulturhistorischen Hintergründe führten zur Motivwahl des Künstlers? Wie verzahnt sind Autobiografie und literarischer Text gerade in der Exilliteratur? Begeben Sie sich gemeinsam mit Ihren Schüler_innen und der Familie Mann ins Exil und schlagen Sie den Bogen in die Gegenwart, welcher erschreckende Zyklen, sprachliche Redundanzen und wiederkehrende Bilder offenbart. Wir wünschen allen Besucher_innen unserer Ausstellung spannende Blickwinkel, anregende Momente und interessante Gespräche! 2 INHALT 4 _Die Ausstellung 6 _Die Familie Mann (Ursula Häckermann) 33 _Die historischen Hintergründe (Irena Trivonoff Ilieff) 51 _Die Exilliteratur (Ursula Häckermann) 74 _Die Aktualität (Irena Trivonoff Ilieff) 80 _Literaturverzeichnis 88 _Wichtige Infos 3 DIE AUSSTELLUNG Als Literaturhaus ist das täglich’ Brot des Buddenbrookhauses das Ausstellen von Literatur. Aber wie präsentiert man Literatur? Wie vermittelt man auf moderne und nachhaltige Weise die kulturhistorischen Hintergründe, die literarischen Einflüsse und die ganz persönlichen Impulse von Autoren? Die Sonderausstellung „Fremde Heimat.