The Zweigesque in Wes Anderson's "The Grand Budapest Hotel"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EE British Academy Film Awards Sunday 8 February 2015

EE British Academy Film Awards Sunday 8 February 2015 Previous Nominations and Wins in EE British Academy Film Awards only. Includes this year’s nominations. Wins in bold. Leading Actor Benedict Cumberbatch 1 nomination Leading Actor in 2015: The Imitation Game Eddie Redmayne 1 nomination Leading Actor in 2015: The Theory of Everything Orange Wednesdays Rising Star Award Nominee in 2012 Jake Gyllenhaal 2 nominations / 1 win Supporting Actor in 2006: Brokeback Mountain Leading Actor in 2015: Nightcrawler Michael Keaton 1 nomination Leading Actor in 2015: Birdman Ralph Fiennes 6 nominations / 1 win Supporting Actor in 1994: Schindler’s List Leading Actor in 1997: The English Patient Leading Actor in 2000: The End of The Affair Leading Actor in 2006: The Constant Gardener Outstanding Debut by a British Writer, Director or Producer in 2012: Coriolanus (as Director) Leading Actor in 2015: The Grand Budapest Hotel Leading Actress Amy Adams 5 nominations Supporting Actress in 2009: Doubt Supporting Actress in 2011: The Fighter Supporting Actress in 2013: The Master Leading Actress in 2014: American Hustle Leading Actress in 2015: Big Eyes Felicity Jones 1 nomination Leading Actress in 2015: The Theory of Everything Julianne Moore 4 nominations Leading Actress in 2000: The End of the Affair Supporting Actress in 2003: The Hours Leading Actress in 2011: The Kids are All Right Leading Actress in 2015: Still Alice Reese Witherspoon 2 nominations / 1 win Leading Actress in 2006: Walk the Line Leading Actress in 2015: Wild Rosamund Pike 1 nomination Leading Actress in 2015: Gone Girl Supporting Actor Edward Norton 2 nominations Supporting Actor in 1997: Primal Fear Supporting Actor in 2015: Birdman Ethan Hawke 1 nomination Supporting Actor in 2015: Boyhood J. -

LIST of MOVIES from PAST SFFR MOVIE NIGHTS (Ordered from Recent to Old) *See Editing Instructions at Bottom of Document

LIST OF MOVIES FROM PAST SFFR MOVIE NIGHTS (Ordered from recent to old) *See editing Instructions at bottom of document 2020: Jan – Judy Feb – Papi Chulo Mar - Girl Apr - GAME OVER, MAN May - Circus of Books 2019: Jan – Mario Feb – Boy Erased Mar – Cakemaker Apr - The Sum of Us May – The Pass June – Fun in Boys Shorts July – The Way He Looks Aug – Teen Spirit Sept – Walk on the Wild Side Oct – Rocketman Nov – Toy Story 4 2018: Jan – Stronger Feb – God’s Own Country Mar -Beach Rats Apr -The Shape of Water May -Cuatras Lunas( 4 Moons) June -The Infamous T and Gay USA July – Padmaavat Aug – (no movie night) Sep – The Unknown Cyclist Oct - Love, Simon Nov – Man in an Orange Shirt Dec – Mama Mia 2 2017: Dec – Eat with Me Nov – Wonder Woman (2017 version) Oct – Invaders from Mars Sep – Handsome Devil Aug – Girls Trip (at Westfield San Francisco Centre) Jul – Beauty and the Beast (2017 live-action remake) Jun – San Francisco International LGBT Film Festival selections May – Lion Apr – La La Land Mar – The Heat Feb – Sausage Party Jan – Friday the 13th 2016: Dec - Grandma Nov – Alamo Draft House Movie Oct - Saved Sep – Looking the Movie Aug – Fourth Man Out, Saving Face July – Hail, Caesar June – International Film festival selections May – Selected shorts from LGBT Film Festival Apr - Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (Run, Milkha, Run) Mar – Trainwreck Feb – Inside Out Jan – Best In Show 2015: Dec - Do I Sound Gay? Nov - The best of the Golden Girls / Boys Oct - Love Songs Sep - A Single Man Aug – Bad Education Jul – Five Dances Jun - Broad City series May – Reaching for the Moon Apr - Boyhood Mar - And Then Came Lola Feb – Looking (Season 2, Episodes 1-4) Jan – The Grand Budapest Hotel 2014: Dec – Bad Santa Nov – Mrs. -

|||GET||| the World of Yesterday 1St Edition

THE WORLD OF YESTERDAY 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Stefan Zweig | 9780803226616 | | | | | [PDF] The World of Yesterday Book by Stefan Zweig Free Download (461 pages) Indriven into exile by the Nazis, he emigrated to England and then, into Brazil by way of New York. Most importantly, each chapter of his The World of Yesterday 1st edition made me appreciate a time and era when books were prominent and intellectual discussion was paramount. As an Autrian-Jewish writer who experienced both World Wars and encountered numerous influencial and interesting people in his life, I expected Zweig would have a facinating story to tell. Everyone collapses with the Sarajevo bombing. Stefan Zweig even claims that the purpose of the school was to discipline and calm the ardor of the youth. Let's try this one more time. There are some very interesting insights in the Hitler chapter, but Zweig soon escaped and lived in relative peace, and so was not the best witness as he admits for the events he subsequently lived through. Our day is gone. Condition: Very Fine. Like his odd friendship with Rathenau, apparently conducted entirely in moving vehicles and the spaces between appointments, watching a powerful mind NOT engaged exclusively with Art but able to understand itnavigate the world. The fact that Zweig and his wife both committed suicide during the war, e I read the first hundred pages or so which painted a vivid picture of life in the waning days of the Hapsburg empire, the patronage of arts, the stability and security felt by everyone, the Jewish community's dynamism, and schooling and university. -

The Grand Budapest Hotel” Jamie L

Cinesthesia Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 1 4-21-2017 Faint Glimmers of Civilization: Mediated Nostalgia and “The Grand Budapest Hotel” Jamie L. Bick Grand Valley State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine Part of the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bick, Jamie L. (2017) "Faint Glimmers of Civilization: Mediated Nostalgia and “The Grand Budapest Hotel”," Cinesthesia: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine/vol6/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cinesthesia by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bick: Mediated Nostalgia and "The Grand Budapest Hotel" Faint Glimmers of Civilization: Mediated Nostalgia and The Grand Budapest Hotel by Jamie Bick As a tool of an uncritical, backwards-gazing “media-defined past” (Lizardi 137), mediated nostalgia is increasingly concerned with how “persuasion through the pop culture of preceding generations” can be used to integrate an often-unlived past into the modern viewer's identity and worldview (De Revere, par. 5). Mediated nostalgia is akin to the neologism “legislated nostalgia,” coined by Douglas Coupland in his 1991 novel Generation X, and described as the process of “forc[ing] a body of people to have memories they do not actually possess” (Coupland 41); corporations likely use this process to market and sell a viewer's nostalgia back to them. While the nostalgic assimilation sought by the viewer is ultimately achieved through the repeated psychological absorption of various media, often with the aid of democratized media technologies like the Internet, the embrace of mediated nostalgia by film is not entirely nefarious and capitalistic. -

Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann

Naharaim 2014, 8(2): 210–226 Uri Ganani and Dani Issler The World of Yesterday versus The Turning Point: Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann “A turning point in world history!” I hear people saying. “The right moment, indeed, for an average writer to call our attention to his esteemed literary personality!” I call that healthy irony. On the other hand, however, I wonder if a turning point in world history, upon careful consideration, is not really the moment for everyone to look inward. Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man1 Abstract: This article revisits the world-views of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann by analyzing the diverse ways in which they shaped their literary careers as autobiographers. Particular focus is given to the crises they experienced while composing their respective autobiographical narratives, both published in 1942. Our re-evaluation of their complex discussions on literature and art reveals two distinctive approaches to the relationship between aesthetics and politics, as well as two alternative concepts of authorial autonomy within society. Simulta- neously, we argue that in spite of their different approaches to political involve- ment, both authors shared a basic understanding of art as an enclave of huma- nistic existence at a time of oppressive political circumstances. However, their attitudes toward the autonomy of the artist under fascism differed greatly. This is demonstrated mainly through their contrasting portrayals of Richard Strauss, who appears in both autobiographies as an emblematic genius composer. DOI 10.1515/naha-2014-0010 1 Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man, trans. -

Barbie Bake-Off and Risk Or Role the Apprentice Model? Documentary Pokémon Go Shorts

FEBRUARY 2017 ISSUE 59 POST-TRUTH RESEARCHING THE PAST BARBIE BAKE-OFF AND RISK OR ROLE THE APPRENTICE MODEL? DOCUMENTARY POKÉMON GO SHORTS MM59_cover_4_feb.indd 1 06/02/2017 14:00 Contents 04 Making the Most of MediaMag MediaMagazine is published by the English and Media 06 What’s the Truth in a Centre, a non-profit making Post-fact World? organisation. The Centre Nick Lacey explores the role publishes a wide range of of misinformation in recent classroom materials and electoral campaigns, and runs courses for teachers. asks who is responsible for If you’re studying English 06 gate-keeping online news. at A Level, look out for emagazine, also published 10 NW and the Image by the Centre. System at Work in the World Andrew McCallum explores the complexities of image and identify in the BBC television 30 16 adaptation of Zadie Smith’s acclaimed novel, NW. 16 Operation Julie: Researching the Past Screenwriter Mike Hobbs describes the challenges of researching a script for a sensational crime story forty years after the event. 20 20 Bun Fight: How The BBC The English and Media Centre 18 Compton Terrace Lost Bake Off to Channel 4 London N1 2UN and Why it Matters Telephone: 020 7359 8080 Jonathan Nunns examines Fax: 020 7354 0133 why the acquisition of Bake Email for subscription enquiries: Off may be less than a bun [email protected] in the oven for Channel 4. 25 Mirror, Mirror, on the Editor: Jenny Grahame Wall… Mark Ramey introduces Copy-editing: some of the big questions we Andrew McCallum should be asking about the Subscriptions manager: nature of documentary film Bev St Hill 10 and its relationship to reality. -

Isle of Dogs (Dir

Nick Davis Film Discussion Group April 2018 Isle of Dogs (dir. Wes Anderson, 2018) Dog Cast Chief (the main dog): Bryan Cranston: One of the only non-Anderson vets in the U.S. cast Rex (a semi-leader): Edward Norton: Moonrise Kingdom (12); Grand Budapest Hotel (14) Duke (gossip fan): Jeff Goldblum: fantastic in underseen British gem Le Week-end (13) Boss (mascot jersey): Bill Murray: rebooted career by starring in Anderson’s Rushmore (98) King (in their crew): Bob Balaban: hilarious in a very different dog movie, Best in Show (00) Spots (Atari’s dog): Liev Schreiber: oft-cast as dour antiheroes: Ray Donovan (13-18), etc. Nutmeg (Chief’s crush): Scarlett Johansson: controversially appeared in Ghost in the Shell (17) Jupiter (wise hermit): F. Murray Abraham: won Best Actor Oscar as Salieri in Amadeus (84) Oracle (TV prophet): Tilda Swinton: an Anderson regular since Moonrise Kingdom (12) Gondo (lead “cannibal”): Harvey Keitel: untrue rumors of cruelty a riff on his usual typecasting Peppermint (Spots’ girl): Kara Hayward: the young female co-lead of Moonrise Kingdom (12) Human Cast Atari (young pilot): Koyu Rankin: Japanese-Scottish-Canadian, in his first feature film Kobayashi (evil mayor): Kunichi Nomura: enlisted as Japanese cultural consultant, then cast Prof. Watanabe: Akiro Ito: actor/dancer; briefly appears as translator in Birdman (14) Interpreter Nelson: Frances McDormand: another veteran of Moonrise Kingdom (12) Tracy (U.S. student): Greta Gerwig: the Oscar-nominated writer-director of Lady Bird (17) Yoko Ono (scientist): Yoko Ono: 83-year-old avant-garde musician and performance artist Narrator: Courtney B. -

Nostalgia for Fin De Siècle Vienna

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU Experiential Learning & Community Celebrating Scholarship & Creativity Day Engagement 4-24-2014 Much more than longing: Nostalgia for Fin de Siècle Vienna Dana Hicks College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/elce_cscday Part of the European History Commons, and the Intellectual History Commons Recommended Citation Hicks, Dana, "Much more than longing: Nostalgia for Fin de Siècle Vienna" (2014). Celebrating Scholarship & Creativity Day. 28. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/elce_cscday/28 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Celebrating Scholarship & Creativity Day by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Much More Than Longing: Nostalgia for Fin de Siècle Vienna Dana R. Hicks HIST 399: Senior Thesis Dr. Schroeder March 19, 2014 Hicks 2 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Historiography ........................................................................................................................................... 5 A Modern Understanding of Nostalgia ................................................................................................ 11 Sources of Nostalgia -

89Th Annual Academy Awards® Oscar® Nominations Fact

® 89TH ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS ® OSCAR NOMINATIONS FACT SHEET Best Motion Picture of the Year: Arrival (Paramount) - Shawn Levy, Dan Levine, Aaron Ryder and David Linde, producers - This is the first nomination for all four. Fences (Paramount) - Scott Rudin, Denzel Washington and Todd Black, producers - This is the eighth nomination for Scott Rudin, who won for No Country for Old Men (2007). His other Best Picture nominations were for The Hours (2002), The Social Network (2010), True Grit (2010), Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (2011), Captain Phillips (2013) and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). This is the first nomination in this category for both Denzel Washington and Todd Black. Hacksaw Ridge (Summit Entertainment) - Bill Mechanic and David Permut, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hell or High Water (CBS Films and Lionsgate) - Carla Hacken and Julie Yorn, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hidden Figures (20th Century Fox) - Donna Gigliotti, Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi, producers - This is the fourth nomination in this category for Donna Gigliotti, who won for Shakespeare in Love (1998). Her other Best Picture nominations were for The Reader (2008) and Silver Linings Playbook (2012). This is the first nomination in this category for Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi. La La Land (Summit Entertainment) - Fred Berger, Jordan Horowitz and Marc Platt, producers - This is the first nomination for both Fred Berger and Jordan Horowitz. This is the second nomination in this category for Marc Platt. He was nominated last year for Bridge of Spies. Lion (The Weinstein Company) - Emile Sherman, Iain Canning and Angie Fielder, producers - This is the second nomination in this category for both Emile Sherman and Iain Canning, who won for The King's Speech (2010). -

Films Winning 4 Or More Awards Without Winning Best Picture

FILMS WINNING 4 OR MORE AWARDS WITHOUT WINNING BEST PICTURE Best Picture winner indicated by brackets Highlighted film titles were not nominated in the Best Picture category [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] 8 AWARDS Cabaret, Allied Artists, 1972. [The Godfather] 7 AWARDS Gravity, Warner Bros., 2013. [12 Years a Slave] 6 AWARDS A Place in the Sun, Paramount, 1951. [An American in Paris] Star Wars, 20th Century-Fox, 1977 (plus 1 Special Achievement Award). [Annie Hall] Mad Max: Fury Road, Warner Bros., 2015 [Spotlight] 5 AWARDS Wilson, 20th Century-Fox, 1944. [Going My Way] The Bad and the Beautiful, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1952. [The Greatest Show on Earth] The King and I, 20th Century-Fox, 1956. [Around the World in 80 Days] Mary Poppins, Buena Vista Distribution Company, 1964. [My Fair Lady] Doctor Zhivago, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1965. [The Sound of Music] Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Warner Bros., 1966. [A Man for All Seasons] Saving Private Ryan, DreamWorks, 1998. [Shakespeare in Love] The Aviator, Miramax, Initial Entertainment Group and Warner Bros., 2004. [Million Dollar Baby] Hugo, Paramount, 2011. [The Artist] 4 AWARDS The Informer, RKO Radio, 1935. [Mutiny on the Bounty] Anthony Adverse, Warner Bros., 1936. [The Great Ziegfeld] The Song of Bernadette, 20th Century-Fox, 1943. [Casablanca] The Heiress, Paramount, 1949. [All the King’s Men] A Streetcar Named Desire, Warner Bros., 1951. [An American in Paris] High Noon, United Artists, 1952. [The Greatest Show on Earth] Sayonara, Warner Bros., 1957. [The Bridge on the River Kwai] Spartacus, Universal-International, 1960. [The Apartment] Cleopatra, 20th Century-Fox, 1963. -

Stefan Zweig at the End of the World Pdf, Epub, Ebook

STEFAN ZWEIG AT THE END OF THE WORLD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK George Prochnik | 396 pages | 05 Jun 2014 | Other Press LLC | 9781590516126 | English | New York, United States Stefan Zweig at the End of the World PDF Book Other editions. He feels the need to bear witness to the next generation of what his age has gone through, mostly since it has known almost everything due to the better dissemination of information and the total involvement of the populations in the conflicts: wars First World War, Second World War , famines, epidemics, economic crisis, etc. They'd passed through the same faith-obliterating war, and lived with the lingering socioeconomic devastation of that conflict. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Regarding the author's narrative strategy and design. Now I have the context. And of course, when the Nazis blew his favorite venues and stages to little tiny bits and the cheering of adoring, star-struck audiences stopped, Zweig couldn't cope - precisely because there was nothing to him at all except shell and surface. A turning point took place in their fortnight: school no longer satisfied their passion, which shifted to the art of which Vienna was the heart. Zweig thought it prudent not to be present. The reader, too, can feel a bit at sea, or like a guest at a party shuttling down a hectic receiving line. Retrieved 4 May His life was beautiful and it was tragic. Photos I thought were of Zweig's family turn out upon getting to the the photo list at the very end of the book to be from Prochnik's own family. -

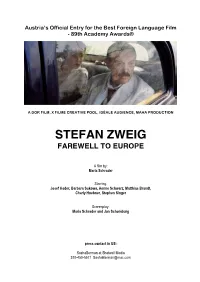

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant,