Nostalgia for Fin De Siècle Vienna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

|||GET||| the World of Yesterday 1St Edition

THE WORLD OF YESTERDAY 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Stefan Zweig | 9780803226616 | | | | | [PDF] The World of Yesterday Book by Stefan Zweig Free Download (461 pages) Indriven into exile by the Nazis, he emigrated to England and then, into Brazil by way of New York. Most importantly, each chapter of his The World of Yesterday 1st edition made me appreciate a time and era when books were prominent and intellectual discussion was paramount. As an Autrian-Jewish writer who experienced both World Wars and encountered numerous influencial and interesting people in his life, I expected Zweig would have a facinating story to tell. Everyone collapses with the Sarajevo bombing. Stefan Zweig even claims that the purpose of the school was to discipline and calm the ardor of the youth. Let's try this one more time. There are some very interesting insights in the Hitler chapter, but Zweig soon escaped and lived in relative peace, and so was not the best witness as he admits for the events he subsequently lived through. Our day is gone. Condition: Very Fine. Like his odd friendship with Rathenau, apparently conducted entirely in moving vehicles and the spaces between appointments, watching a powerful mind NOT engaged exclusively with Art but able to understand itnavigate the world. The fact that Zweig and his wife both committed suicide during the war, e I read the first hundred pages or so which painted a vivid picture of life in the waning days of the Hapsburg empire, the patronage of arts, the stability and security felt by everyone, the Jewish community's dynamism, and schooling and university. -

Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann

Naharaim 2014, 8(2): 210–226 Uri Ganani and Dani Issler The World of Yesterday versus The Turning Point: Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann “A turning point in world history!” I hear people saying. “The right moment, indeed, for an average writer to call our attention to his esteemed literary personality!” I call that healthy irony. On the other hand, however, I wonder if a turning point in world history, upon careful consideration, is not really the moment for everyone to look inward. Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man1 Abstract: This article revisits the world-views of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann by analyzing the diverse ways in which they shaped their literary careers as autobiographers. Particular focus is given to the crises they experienced while composing their respective autobiographical narratives, both published in 1942. Our re-evaluation of their complex discussions on literature and art reveals two distinctive approaches to the relationship between aesthetics and politics, as well as two alternative concepts of authorial autonomy within society. Simulta- neously, we argue that in spite of their different approaches to political involve- ment, both authors shared a basic understanding of art as an enclave of huma- nistic existence at a time of oppressive political circumstances. However, their attitudes toward the autonomy of the artist under fascism differed greatly. This is demonstrated mainly through their contrasting portrayals of Richard Strauss, who appears in both autobiographies as an emblematic genius composer. DOI 10.1515/naha-2014-0010 1 Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man, trans. -

Stefan Zweig at the End of the World Pdf, Epub, Ebook

STEFAN ZWEIG AT THE END OF THE WORLD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK George Prochnik | 396 pages | 05 Jun 2014 | Other Press LLC | 9781590516126 | English | New York, United States Stefan Zweig at the End of the World PDF Book Other editions. He feels the need to bear witness to the next generation of what his age has gone through, mostly since it has known almost everything due to the better dissemination of information and the total involvement of the populations in the conflicts: wars First World War, Second World War , famines, epidemics, economic crisis, etc. They'd passed through the same faith-obliterating war, and lived with the lingering socioeconomic devastation of that conflict. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Regarding the author's narrative strategy and design. Now I have the context. And of course, when the Nazis blew his favorite venues and stages to little tiny bits and the cheering of adoring, star-struck audiences stopped, Zweig couldn't cope - precisely because there was nothing to him at all except shell and surface. A turning point took place in their fortnight: school no longer satisfied their passion, which shifted to the art of which Vienna was the heart. Zweig thought it prudent not to be present. The reader, too, can feel a bit at sea, or like a guest at a party shuttling down a hectic receiving line. Retrieved 4 May His life was beautiful and it was tragic. Photos I thought were of Zweig's family turn out upon getting to the the photo list at the very end of the book to be from Prochnik's own family. -

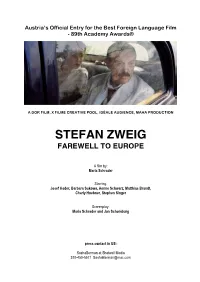

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

The Zweigesque in Wes Anderson's "The Grand Budapest Hotel"

THE ZWEIGESQUE IN WES ANDERSON’S “THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL” Malorie Spencer A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2018 Committee: Edgar Landgraf, Advisor Kristie Foell ii ABSTRACT Edgar Landgraf, Advisor This thesis examines the parallels between narrative structures, including frame narratives and narrative construction of identity, as well as poetic and thematic parallels that exist between the writings of Stefan Zweig and the Wes Anderson film, The Grand Budapest Hotel. These parallels are discussed in order to substantiate Anderson’s claim that The Grand Budapest Hotel is a zweigesque film despite the fact that it is not a direct film adaptation of any one Zweig work. Anderson’s adaptations of zweigesque elements show that Zweig’s writings continue to be relevant today. These adaptations demonstrate the intricate ways in which narrative devices can be used to construct stories and reconstruct history. By drawing on thematic and stylistic elements of Zweig’s writings, Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel raises broader questions about both the necessity of narratives and their shortcomings in the construction of identity; Anderson’s characters both rely on and challenge the ways identity is constructed through narrative. This thesis shows how the zweigesque in Anderson’s film is able to challenge how history is viewed and how people conceptualize and relate to their continually changing notions of identity. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my family for their encouragement throughout the process of writing this thesis. -

We Need a Completely Different Kind of Courage.« Stefan Zweig – Farewell to Europe

»We need a completely different kind of courage.« Stefan Zweig – Farewell to Europe With his wife, Lotte, Stefan Zweig boarded the British passenger ship Scythia on the evening of 25 June 1940 and sailed from Liverpool to New York. Neither of them was ever to see Europe again. In February 1934 Zweig had moved out of his house in Salzburg. One year earlier Hitler had become chancellor of the German Reich, and life in Austria as well became characterized by the intolerance and hostility of those in power to the intellectual spirit. The first stop in Zweig’s exile was London, where he wrote his biography of Mary Stuart and the novel Ungeduld des Herzens (Beware of Pity). After divorcing his first wife in 1938, Zweig married his London secretary, Charlotte Elisabeth Altmann, a German emigrant, in September 1939. Both of them adopted British citizenship and lived for a few months in Bath before crossing the Atlantic. In February 1942, their suicide in the Brazilian city of Petrópolis made news around the world. The exhibition focuses on the scenario of parting: we look back on the lost »world of security« that Stefan Zweig described with great feeling in his me- Room 3 moirs. By this time the Belle Époque was already history, Europe was at war, On Saturday, 21 February 1942, one day before committing suicide with his wife, the paintings had been taken down from the walls, the carpets rolled up, and Stefan Zweig took the typescript of Schachnovelle (The Royal Game) to the post the packing cases were ready to go. -

Matthew D. Goodwin the Brazilian Exile of Vilém Flusser and Stefan Zweig

FLUSSER STUDIES 07 Matthew D. Goodwin The Brazilian Exile of Vilém Flusser and Stefan Zweig Vilém Flusser (1920-1991) landed in Brazil at the end of 1940, fleeing Nazi Europe, and was told on arriving that his father had died; the rest of his family would die in the concentration camps. He survived, even flourished, and again picked up to travel, eventually moving back to Europe in the 1971. Flusser produced the beginnings of a unique philosophy of immigration that focused consistently on the freedom and creativity made possible by exile. Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) also fled Nazi Europe, and after visiting Brazil as a celebrated author in 1936 and 1940, eventually decided to remain there in 1941. In February of 1942 he committed suicide with his wife. There are many interesting parallels to be found between Flusser and Zweig which deserve attention, their writings on Brazilian history and culture, and Judaism for example. In this paper, however, I will offer a preliminary comparison of Flusser’s philosophy of immigration and Zweig’s last work of fiction, Schachnovelle. These works will be contextualized in the history of Jewish exile to Brazil and the Brazilian government’s policies towards Jews around the time of their arrival. Flusser and Zweig share a dialectical form of thinking which constantly emphasizes the search for a synthesis, and yet Zweig expresses the failure of finding that synthesis due to exile and the loss of European culture, while Flusser finds the synthesis in the experience of immigration itself. At the moment Flusser -

Stefan Zweig and Historical Displacement in Brazil, 1941-1942

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-19-2017 'In This Dark Hour': Stefan Zweig and Historical Displacement in Brazil, 1941-1942 Edward Lawrence University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the European History Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence, Edward, "'In This Dark Hour': Stefan Zweig and Historical Displacement in Brazil, 1941-1942" (2017). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2334. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2334 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ‘In this Dark Hour’: Stefan Zweig and Historical Displacement in Brazil, 1941-1942 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by Edward Lawrence B.A., The University of Virginia’s College at Wise, 2015 May, 2017 Acknowledgements I would like to thank a number of individuals who made this project possible. -

Uvic Thesis Template

Richard Strauss’s Friedenstag : A Political Statement of Peace in Nazi Germany by Patricia Josette Moss Bachelor of Arts, University of Montevallo, 2004 Master of Music, Louisiana State University, 2006 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the School of Music Patricia Josette Moss, 2010 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Richard Strauss’s Friedenstag : A Political Statement of Peace in Nazi Germany by Patricia Josette Moss Bachelor of Arts, University of Montevallo, 2004 Master of Music, Louisiana State University, 2006 Supervisory Committee Dr. Jonathan Goldman, School of Music Supervisor Dr. Michelle Fillion, School of Music Departmental Member Dr. Helga Thorson, Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies Outside Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Jonathan Goldman Supervisor Dr. Michelle Fillion Departmental Member Dr. Helga Thorson Outside Member After the conclusion of World War II, Richard Strauss’s activities and compositions came under intense scrutiny as scholars tried to understand his position with respect to the National Socialist regime. Their conclusions varied, some describing Strauss as a Nazi sympathizer, some as a victim of Nazism, with others concluding that Strauss was neither a sympathizer nor a victim, merely politically naïve. Among the latter was Strauss’s friend and biographer, Willi Schuh, who ardently defended the composer’s activities during the Nazi period. While Schuh asserted that Strauss’s music had no direct political ties to the “Third Reich”, Strauss’s 1938 opera, Friedenstag , demonstrates that he was, in fact, politically aware and capable of composing a work replete with conscious political overtones. -

Fantastic Night Tales of Longing and Liberation 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

FANTASTIC NIGHT TALES OF LONGING AND LIBERATION 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Stefan Zweig | 9781782271482 | | | | | Fantastic Night Tales of Longing and Liberation 1st edition PDF Book Fantastic Night provides a mixture of novellas and short stories, many of which I hadn't come across before. Categories :. Herr Mendel breaks my heart. It was like this even before and even now. I though the tenderness was only for me, for me alone, and in that one second, the woman latent in my adolescent self awoke, and she in thrall to you for ever. Lists with This Book. As the fictional play, it has been originally written in French before being translated, then banned in Britain because of its scandalous reputation. The Invisible Collection 4. I have shared smokes and alcohol with homeless people on the parks and tried to join a conversation with them and even got robbed once. You may also like. I was really excited about this book because of the reviews i have read. The story reveals, over time, that Hildred has both read the play The King In Yellow and suffered a nasty fall — each of which are, it is suggested, partway responsible for his delusions of grandeur and his attempts to ensure his ascent to the throne. How many successful vacuous people do you know? Zweig is a masterfully perceptive author, and there was such a difference to every one of the stories here. I felt sorry for the unreciprocated love towards the romantic woman who admired the hero so much. Maybe I need a night like he had. -

Arendt Wrote a Review of a German Book That — in the Middle of the War — Was Available to Her Only in English Translation

einen Staatenlosenpaß erbitten. […] Ebenso verstand ich erst in der Minute, da ich nach längerem Warten auf der Bittstellerbank des Vorraums in die englische Amtsstube einge- lassen wurde, was dieser Umtausch meines Passes gegen ein Fremdenpapier bedeutete. Denn auf meinen österreichischen Paß hatte ich ein Anrecht gehabt. Jeder österreichische Konsulatsbeamte oder Polizeioffizier war verpflichtet gewesen, ihn mir als vollberech- tigten Bürger sofort auszustellen. Das englische Fremdenpapier dagegen, das ich erhielt, mußte ich erbitten. Es war eine erbetene Gefälligkeit und eine Gefälligkeit überdies, die mir jeden Augenblick entzogen werden konnte. Über Nacht war ich abermals eine Stufe hinuntergeglitten. Gestern noch ausländischer Gast und gewissermaßen Gentleman, der hier sein internationales Einkommen verausgabte und seine Steuern bezahlte, war ich Emigrant geworden, ein ›Refugee‹.« Zweig: Die Welt von gestern, 462-463. 95 35 »The Great Silence« ] »ONA, March 9, 1942«. Anmerkung im Text. Der Aufsatz war unter demselben Titel in der Neuen Volkszeitung [New York] vom 22. Juni 1940, 2, erschienen. Eine englische Übersetzung dieser Fassung, »The Great Si- lence«, übersetzt von William G. Phelps, erschien in: The Shreveport Times [Shreveport], 30. Juni 1940, 5. Die von Arendt genannte Fassung des Aufsatzes (ONA, March 9, 1942), die fast zwei Jahre später erschien, konnte nicht nachgewiesen werden. Zweig: Das große Schweigen (Neue Volkszeitung). 95 35-36 kurz vor seinem Tode ] Stefan Zweig hatte am 22. Februar 1942 Selbstmord began- gen. 96 4-6 »als sei ein … worden«, ] Stefan Zweigs Essay »Das große Schweigen« beginnt mit den Worten: »Ich glaube, dass die erste Pflicht aller, die die Freiheit des Redens haben, heute die ist, im Namen der Millionen und Abermillionen zu sprechen, die es selber nicht mehr können, weil dieses unentwendbare Recht ihnen entwendet worden ist.« Für »vier- zig oder fünfzig Millionen Opfer« will der Schreiber sprechen, »deren Stimmen in Mittel- europa erstickt, erdrosselt ist«. -

VOLUME 2, 2006 the Vienna of Hitler and Freud

VOLUME 2, 2006 The Vienna of Hitler and Freud: An Undergraduate Seminar Course Ian Reifowitz SUNY-Empire State College This essay discusses “The Vienna of Hitler and Freud,” a seminar course that examines the culture of the Habsburg capital in the period from 1867 through 1938, with a particular focus on the years just before and after 1900. The goal of this course was twofold. First, it sought to introduce students to broad historical debates about the nature of Viennese fin-de-siècle culture by having them read political and cultural histories about that society. Then, it asked them to read important works of fiction and non-fiction produced in that society and attempt to assess how accurately these works reflected each of the historical arguments they had previously discussed. This approach can produce fruitful results with well-prepared, motivated students at many different kinds of post- secondary institutions. Teaching Austria, Volume 2 (2006) 89 More broadly, the goal of this kind of seminar is for students to gain an understanding of how to study in depth any historical topic or period of time. I sought to develop their analytical skills in examining primary and secondary sources. Furthermore, I encouraged them to look for common themes across their sources that reflect broad trends in a given society and culture. The course was designed to impart skills that will hopefully aid students in any kind of advanced study they might eventually undertake, either in or outside of academia. Course Context and Requirements I offered "The Vienna of Hitler and Freud" as an upper-level (i.e.