VOLUME 2, 2006 the Vienna of Hitler and Freud

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

|||GET||| the World of Yesterday 1St Edition

THE WORLD OF YESTERDAY 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Stefan Zweig | 9780803226616 | | | | | [PDF] The World of Yesterday Book by Stefan Zweig Free Download (461 pages) Indriven into exile by the Nazis, he emigrated to England and then, into Brazil by way of New York. Most importantly, each chapter of his The World of Yesterday 1st edition made me appreciate a time and era when books were prominent and intellectual discussion was paramount. As an Autrian-Jewish writer who experienced both World Wars and encountered numerous influencial and interesting people in his life, I expected Zweig would have a facinating story to tell. Everyone collapses with the Sarajevo bombing. Stefan Zweig even claims that the purpose of the school was to discipline and calm the ardor of the youth. Let's try this one more time. There are some very interesting insights in the Hitler chapter, but Zweig soon escaped and lived in relative peace, and so was not the best witness as he admits for the events he subsequently lived through. Our day is gone. Condition: Very Fine. Like his odd friendship with Rathenau, apparently conducted entirely in moving vehicles and the spaces between appointments, watching a powerful mind NOT engaged exclusively with Art but able to understand itnavigate the world. The fact that Zweig and his wife both committed suicide during the war, e I read the first hundred pages or so which painted a vivid picture of life in the waning days of the Hapsburg empire, the patronage of arts, the stability and security felt by everyone, the Jewish community's dynamism, and schooling and university. -

Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann

Naharaim 2014, 8(2): 210–226 Uri Ganani and Dani Issler The World of Yesterday versus The Turning Point: Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann “A turning point in world history!” I hear people saying. “The right moment, indeed, for an average writer to call our attention to his esteemed literary personality!” I call that healthy irony. On the other hand, however, I wonder if a turning point in world history, upon careful consideration, is not really the moment for everyone to look inward. Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man1 Abstract: This article revisits the world-views of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann by analyzing the diverse ways in which they shaped their literary careers as autobiographers. Particular focus is given to the crises they experienced while composing their respective autobiographical narratives, both published in 1942. Our re-evaluation of their complex discussions on literature and art reveals two distinctive approaches to the relationship between aesthetics and politics, as well as two alternative concepts of authorial autonomy within society. Simulta- neously, we argue that in spite of their different approaches to political involve- ment, both authors shared a basic understanding of art as an enclave of huma- nistic existence at a time of oppressive political circumstances. However, their attitudes toward the autonomy of the artist under fascism differed greatly. This is demonstrated mainly through their contrasting portrayals of Richard Strauss, who appears in both autobiographies as an emblematic genius composer. DOI 10.1515/naha-2014-0010 1 Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man, trans. -

Svetozar Borevic, South Slav Habsburg Nationalism, and the First World War

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-17-2021 Fuer Kaiser und Heimat: Svetozar Borevic, South Slav Habsburg Nationalism, and the First World War Sean Krummerich University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Krummerich, Sean, "Fuer Kaiser und Heimat: Svetozar Borevic, South Slav Habsburg Nationalism, and the First World War" (2021). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/8808 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Für Kaiser und Heimat: Svetozar Boroević, South Slav Habsburg Nationalism, and the First World War by Sean Krummerich A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History College of Arts & Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Kees Boterbloem, Ph.D. Darcie Fontaine, Ph.D. J. Scott Perry, Ph.D. Golfo Alexopoulos, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 30, 2021 Keywords: Serb, Croat, nationality, identity, Austria-Hungary Copyright © 2021, Sean Krummerich DEDICATION For continually inspiring me to press onward, I dedicate this work to my boys, John Michael and Riley. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the support of a score of individuals over more years than I would care to admit. First and foremost, my thanks go to Kees Boterbloem, Darcie Fontaine, Golfo Alexopoulos, and Scott Perry, whose invaluable feedback was crucial in shaping this work into what it is today. -

Paris by Brett Farmer Openly Gay Paris Mayor Bertrand Delanoë in Front Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, Glbtq, Inc

Paris by Brett Farmer Openly gay Paris mayor Bertrand Delanoë in front Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. of the Louvre Museum in Entry Copyright © 2004, glbtq, inc. 2006. Photograph by Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Wikimedia Commons contributor Jastrow. One of the world's most iconic cities and an influential hub of Western culture, Paris is Image appears under the also a major international glbtq center. Its popular Anglophone nickname, "gay Paree," Creative Commons was coined originally in response to the city's fabled notoriety for hedonism and Attribution ShareAlike License. frivolity, but it could as easily refer to its equal reputation for other kinds of "gayness." Early History As France's capital and most populous city, Paris has long been a natural draw for those seeking to escape the traditional conservatism of provincial France. Michael D. Sibalis notes that Paris's reputation as a focus for queer life in France dates back as far as the Middle Ages, citing as evidence among other things a twelfth-century poet's description of the city as reveling in "the vice of Sodom." Medieval Paris was not exactly a queer paradise, however. Throughout the Middle Ages numerous poor Parisians were regularly convicted and, in some instances, executed for engaging in sodomy and other same-sex activities. Things improved somewhat by the early modern period. While their exact correspondence to contemporary categories of glbtq sexuality is open to debate, well-developed sodomitical subcultures had emerged in Paris by the eighteenth century. Some historians, such as Maurice Lever, claim these subcultures formed a "homosexual world . -

Nostalgia for Fin De Siècle Vienna

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU Experiential Learning & Community Celebrating Scholarship & Creativity Day Engagement 4-24-2014 Much more than longing: Nostalgia for Fin de Siècle Vienna Dana Hicks College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/elce_cscday Part of the European History Commons, and the Intellectual History Commons Recommended Citation Hicks, Dana, "Much more than longing: Nostalgia for Fin de Siècle Vienna" (2014). Celebrating Scholarship & Creativity Day. 28. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/elce_cscday/28 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Celebrating Scholarship & Creativity Day by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Much More Than Longing: Nostalgia for Fin de Siècle Vienna Dana R. Hicks HIST 399: Senior Thesis Dr. Schroeder March 19, 2014 Hicks 2 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Historiography ........................................................................................................................................... 5 A Modern Understanding of Nostalgia ................................................................................................ 11 Sources of Nostalgia -

Stefan Zweig at the End of the World Pdf, Epub, Ebook

STEFAN ZWEIG AT THE END OF THE WORLD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK George Prochnik | 396 pages | 05 Jun 2014 | Other Press LLC | 9781590516126 | English | New York, United States Stefan Zweig at the End of the World PDF Book Other editions. He feels the need to bear witness to the next generation of what his age has gone through, mostly since it has known almost everything due to the better dissemination of information and the total involvement of the populations in the conflicts: wars First World War, Second World War , famines, epidemics, economic crisis, etc. They'd passed through the same faith-obliterating war, and lived with the lingering socioeconomic devastation of that conflict. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Regarding the author's narrative strategy and design. Now I have the context. And of course, when the Nazis blew his favorite venues and stages to little tiny bits and the cheering of adoring, star-struck audiences stopped, Zweig couldn't cope - precisely because there was nothing to him at all except shell and surface. A turning point took place in their fortnight: school no longer satisfied their passion, which shifted to the art of which Vienna was the heart. Zweig thought it prudent not to be present. The reader, too, can feel a bit at sea, or like a guest at a party shuttling down a hectic receiving line. Retrieved 4 May His life was beautiful and it was tragic. Photos I thought were of Zweig's family turn out upon getting to the the photo list at the very end of the book to be from Prochnik's own family. -

Modernity, Horses, and History in Joseph Roth's Radetzkymarsch

This is a repository copy of Modernity, horses, and history in Joseph Roth’s Radetzkymarsch. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/105367/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Niland, R. and Murgatroyd, N.P. (2016) Modernity, horses, and history in Joseph Roth’s Radetzkymarsch. Literature and History, 25 (2). pp. 150-166. ISSN 0306-1973 https://doi.org/10.1177/0306197316667263 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Modernity, Horses, and History in Joseph Roth’s Radetzkymarsch In his 1938 sketch ‘Im Bistro nach Mitternacht’ [‘In the Bistro After Midnight’], Joseph Roth, chronicler of the disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in his best-known novel Radetzkymarsch (1932), wrote of his nocturnal wanderings in the quarters of interwar Paris. -

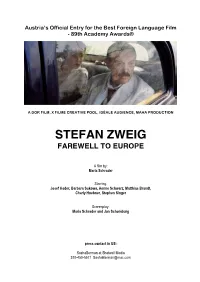

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

The Zweigesque in Wes Anderson's "The Grand Budapest Hotel"

THE ZWEIGESQUE IN WES ANDERSON’S “THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL” Malorie Spencer A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2018 Committee: Edgar Landgraf, Advisor Kristie Foell ii ABSTRACT Edgar Landgraf, Advisor This thesis examines the parallels between narrative structures, including frame narratives and narrative construction of identity, as well as poetic and thematic parallels that exist between the writings of Stefan Zweig and the Wes Anderson film, The Grand Budapest Hotel. These parallels are discussed in order to substantiate Anderson’s claim that The Grand Budapest Hotel is a zweigesque film despite the fact that it is not a direct film adaptation of any one Zweig work. Anderson’s adaptations of zweigesque elements show that Zweig’s writings continue to be relevant today. These adaptations demonstrate the intricate ways in which narrative devices can be used to construct stories and reconstruct history. By drawing on thematic and stylistic elements of Zweig’s writings, Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel raises broader questions about both the necessity of narratives and their shortcomings in the construction of identity; Anderson’s characters both rely on and challenge the ways identity is constructed through narrative. This thesis shows how the zweigesque in Anderson’s film is able to challenge how history is viewed and how people conceptualize and relate to their continually changing notions of identity. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my family for their encouragement throughout the process of writing this thesis. -

The Ends of an Empire: Pier Antonio Quarantotti Gambiniʼs Il Cavallo Tripoli and Joseph Rothʼs Radetzkymarsch

7KH(QGVRIDQ(PSLUH3LHU$QWRQLR4XDUDQWRWWL*DPELQLV ,OFDYDOOR7ULSROLDQG-RVHSK5RWKV5DGHW]N\PDUVFK 6DVNLD(OL]DEHWK=LRONRZVNL Comparative Literature Studies, Volume 52, Number 2, 2015, pp. 349-378 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\3HQQ6WDWH8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/cls/summary/v052/52.2.ziolkowski.html Access provided by Duke University Libraries (3 Aug 2015 12:23 GMT) the ends of an empire: pier antonio quarantotti gambini’s IL CAVALLO TRIPOLI and joseph roth’s RADETZKYMARSCH Saskia Elizabeth Ziolkowski abstract Italian Triestine literature tends to be seen as somewhat foreign to the Italian literary tradition and linguistically outside of Austrian (or Austro-Hungarian) literature. Instead of leaving it as “neither nor,” viewing it as “both and” can help shape the critical view of the Italian literary landscape, as well as add to the picture of Austro-Hungarian literature. Joseph Roth’s Radetzkymarsch (Radetzky March) and Pier Antonio Quarantotti Gambini’s novel Il cavallo Tripoli (The Horse Tripoli) depict the experience of loss brought on by the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in similar ways, although they do so from different linguistic and national sides. However, the writings of the Italian author are generally categorized as representing a pro-Italian perspective and those of the Austrian as pro-Austro-Hungarian. This article argues that their novels provide a more nuanced portrayal of the world and identities than just their nationalities or political views do. Because of assumptions about the authors, the complexity of the novels’ representations of layered linguistic and cultural interactions have often been missed, especially those of Il cavallo Tripoli. -

White Ladies and Dark Continents Sara Lennox

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Cemetery of the Murdered Daughters: Feminism, History, and Ingeborg Bachmann January 2006 Part Three: Reading Bachmann Historically, Chapter 9. Bachmann and Postcolonial Theory: White Ladies and Dark Continents Sara Lennox Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/umpress_cotmd Lennox, Sara, "Part Three: Reading Bachmann Historically, Chapter 9. Bachmann and Postcolonial Theory: White Ladies and Dark Continents" (2006). Cemetery of the Murdered Daughters: Feminism, History, and Ingeborg Bachmann. 10. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/umpress_cotmd/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cemetery of the Murdered Daughters: Feminism, History, and Ingeborg Bachmann by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHAPTER 9 Bachmann and Postcolonial Theory WHITE LADIES AND DARK CONTINENTS . the psyche of the whites, which was obviously more threatened than he could imagine . —Ingeborg Bachmann, The Book of Franza “[Austria] is different from all other little countries today because it was an empire and it’s possible to learn something from its history. And because the lack of activity into which one is forced there enormously sharpens one’s view of the big situation and of today’s empires,” Ingeborg Bachmann observed in a 1971 interview (GuI 106). The postcolonial theory developed since 1990 helps to explain why and how Bachmann was able to use her Austrian vantage point as a privileged perspective from which to regard “today’s empires” and the forms of imperialism for which they have been responsible. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Death in Venice and Other Tales by Thomas Mann Death in Venice and Other Tales PDF Book by Thomas Mann (1911) Download Or Read Online

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Death in Venice and Other Tales by Thomas Mann Death in Venice and Other Tales PDF Book by Thomas Mann (1911) Download or Read Online. Death in Venice and Other Tales PDF book by Thomas Mann Read Online or Free Download in ePUB, PDF or MOBI eBooks. Published in 1911 the book become immediate popular and critical acclaim in fiction, classics books. The main characters of Death in Venice and Other Tales novel are Gustave von Aschenbach, Emma. The book has been awarded with Booker Prize, Edgar Awards and many others. One of the Best Works of Thomas Mann. published in multiple languages including English, consists of 384 pages and is available in Paperback format for offline reading. Death in Venice and Other Tales PDF Details. Author: Thomas Mann Book Format: Paperback Original Title: Death in Venice and Other Tales Number Of Pages: 384 pages First Published in: 1911 Latest Edition: May 1st 1999 Language: English Generes: Fiction, Classics, Short Stories, European Literature, German Literature, Literature, Main Characters: Gustave von Aschenbach Formats: audible mp3, ePUB(Android), kindle, and audiobook. The book can be easily translated to readable Russian, English, Hindi, Spanish, Chinese, Bengali, Malaysian, French, Portuguese, Indonesian, German, Arabic, Japanese and many others. Please note that the characters, names or techniques listed in Death in Venice and Other Tales is a work of fiction and is meant for entertainment purposes only, except for biography and other cases. we do not intend to hurt the sentiments of any community, individual, sect or religion. DMCA and Copyright : Dear all, most of the website is community built, users are uploading hundred of books everyday, which makes really hard for us to identify copyrighted material, please contact us if you want any material removed.