Vienna 1910: a City Without Viennese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

|||GET||| the World of Yesterday 1St Edition

THE WORLD OF YESTERDAY 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Stefan Zweig | 9780803226616 | | | | | [PDF] The World of Yesterday Book by Stefan Zweig Free Download (461 pages) Indriven into exile by the Nazis, he emigrated to England and then, into Brazil by way of New York. Most importantly, each chapter of his The World of Yesterday 1st edition made me appreciate a time and era when books were prominent and intellectual discussion was paramount. As an Autrian-Jewish writer who experienced both World Wars and encountered numerous influencial and interesting people in his life, I expected Zweig would have a facinating story to tell. Everyone collapses with the Sarajevo bombing. Stefan Zweig even claims that the purpose of the school was to discipline and calm the ardor of the youth. Let's try this one more time. There are some very interesting insights in the Hitler chapter, but Zweig soon escaped and lived in relative peace, and so was not the best witness as he admits for the events he subsequently lived through. Our day is gone. Condition: Very Fine. Like his odd friendship with Rathenau, apparently conducted entirely in moving vehicles and the spaces between appointments, watching a powerful mind NOT engaged exclusively with Art but able to understand itnavigate the world. The fact that Zweig and his wife both committed suicide during the war, e I read the first hundred pages or so which painted a vivid picture of life in the waning days of the Hapsburg empire, the patronage of arts, the stability and security felt by everyone, the Jewish community's dynamism, and schooling and university. -

Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann

Naharaim 2014, 8(2): 210–226 Uri Ganani and Dani Issler The World of Yesterday versus The Turning Point: Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann “A turning point in world history!” I hear people saying. “The right moment, indeed, for an average writer to call our attention to his esteemed literary personality!” I call that healthy irony. On the other hand, however, I wonder if a turning point in world history, upon careful consideration, is not really the moment for everyone to look inward. Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man1 Abstract: This article revisits the world-views of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann by analyzing the diverse ways in which they shaped their literary careers as autobiographers. Particular focus is given to the crises they experienced while composing their respective autobiographical narratives, both published in 1942. Our re-evaluation of their complex discussions on literature and art reveals two distinctive approaches to the relationship between aesthetics and politics, as well as two alternative concepts of authorial autonomy within society. Simulta- neously, we argue that in spite of their different approaches to political involve- ment, both authors shared a basic understanding of art as an enclave of huma- nistic existence at a time of oppressive political circumstances. However, their attitudes toward the autonomy of the artist under fascism differed greatly. This is demonstrated mainly through their contrasting portrayals of Richard Strauss, who appears in both autobiographies as an emblematic genius composer. DOI 10.1515/naha-2014-0010 1 Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man, trans. -

Nostalgia for Fin De Siècle Vienna

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU Experiential Learning & Community Celebrating Scholarship & Creativity Day Engagement 4-24-2014 Much more than longing: Nostalgia for Fin de Siècle Vienna Dana Hicks College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/elce_cscday Part of the European History Commons, and the Intellectual History Commons Recommended Citation Hicks, Dana, "Much more than longing: Nostalgia for Fin de Siècle Vienna" (2014). Celebrating Scholarship & Creativity Day. 28. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/elce_cscday/28 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Celebrating Scholarship & Creativity Day by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Much More Than Longing: Nostalgia for Fin de Siècle Vienna Dana R. Hicks HIST 399: Senior Thesis Dr. Schroeder March 19, 2014 Hicks 2 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Historiography ........................................................................................................................................... 5 A Modern Understanding of Nostalgia ................................................................................................ 11 Sources of Nostalgia -

2002 Illinois Shakespeare Festival Program School of Theatre and Dance Illinois State University

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Illinois Shakespeare Festival Fine Arts Summer 2002 2002 Illinois Shakespeare Festival Program School of Theatre and Dance Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/isf Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation School of Theatre and Dance, "2002 Illinois Shakespeare Festival Program" (2002). Illinois Shakespeare Festival. 28. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/isf/28 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Fine Arts at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Illinois Shakespeare Festival by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I LLINOIS SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL Folio A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM ROMEO & JULIET THE MERCHANT OF VENICE 2 5rhSeason THE THEATRE AT EWING MANOR - 2002 "A bed, a bed, my kingdom for a bed ... " You'll fall in love with our beds and a whole lot more at the Hampton Inn Bloomington-Normal. Guaranteed. With complimentary breakfast buffet, free local calls, an outdoor heated pool, and your choice of smoking or non-smoking rooms, plus the opportunity to earn Hilton HHonors hotel points and airline miles. All backed by our 100% Satisfaction Guarantee. If you're not completely satisfied, your night's stay is free. Hampton Inn Bloomington/Normal 604 ½ I.A.A. Drive Bloomington, IL 61701 The closest hotel to the Festival. For reservations call (309) 662-2800 or 1-800 HAMPTON For cellular reservations, call #INN. ~~ ~ 6 o/ ILLINOIS SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL 20oi A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE JUNE 19, 21, 27, 29, JULY 5, 7, 13, 16, 20, 21, 26, 27, AUGUST I, 4, 7, IO czSo ROMEO AND JULIET BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE JUNE 20, 22, 28, 30, JULY 6, 14, 18, 20, 24, 28, 31, AUGUST 2, 8 czSo THE MERCHANT OF VENICE BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE JULY II, 12, 17, 19, 23, 25, 27, 30, AUGUST 3, 6, 9 EWING MANOR, BLOOMINGTON • WESTHOFF THEATRE, NORMAL CALVIN MAcLEAN FERGUS G. -

Stefan Zweig at the End of the World Pdf, Epub, Ebook

STEFAN ZWEIG AT THE END OF THE WORLD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK George Prochnik | 396 pages | 05 Jun 2014 | Other Press LLC | 9781590516126 | English | New York, United States Stefan Zweig at the End of the World PDF Book Other editions. He feels the need to bear witness to the next generation of what his age has gone through, mostly since it has known almost everything due to the better dissemination of information and the total involvement of the populations in the conflicts: wars First World War, Second World War , famines, epidemics, economic crisis, etc. They'd passed through the same faith-obliterating war, and lived with the lingering socioeconomic devastation of that conflict. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Regarding the author's narrative strategy and design. Now I have the context. And of course, when the Nazis blew his favorite venues and stages to little tiny bits and the cheering of adoring, star-struck audiences stopped, Zweig couldn't cope - precisely because there was nothing to him at all except shell and surface. A turning point took place in their fortnight: school no longer satisfied their passion, which shifted to the art of which Vienna was the heart. Zweig thought it prudent not to be present. The reader, too, can feel a bit at sea, or like a guest at a party shuttling down a hectic receiving line. Retrieved 4 May His life was beautiful and it was tragic. Photos I thought were of Zweig's family turn out upon getting to the the photo list at the very end of the book to be from Prochnik's own family. -

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

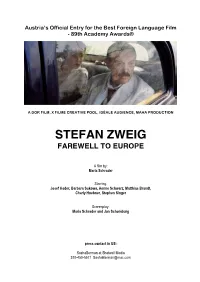

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

The Zweigesque in Wes Anderson's "The Grand Budapest Hotel"

THE ZWEIGESQUE IN WES ANDERSON’S “THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL” Malorie Spencer A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2018 Committee: Edgar Landgraf, Advisor Kristie Foell ii ABSTRACT Edgar Landgraf, Advisor This thesis examines the parallels between narrative structures, including frame narratives and narrative construction of identity, as well as poetic and thematic parallels that exist between the writings of Stefan Zweig and the Wes Anderson film, The Grand Budapest Hotel. These parallels are discussed in order to substantiate Anderson’s claim that The Grand Budapest Hotel is a zweigesque film despite the fact that it is not a direct film adaptation of any one Zweig work. Anderson’s adaptations of zweigesque elements show that Zweig’s writings continue to be relevant today. These adaptations demonstrate the intricate ways in which narrative devices can be used to construct stories and reconstruct history. By drawing on thematic and stylistic elements of Zweig’s writings, Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel raises broader questions about both the necessity of narratives and their shortcomings in the construction of identity; Anderson’s characters both rely on and challenge the ways identity is constructed through narrative. This thesis shows how the zweigesque in Anderson’s film is able to challenge how history is viewed and how people conceptualize and relate to their continually changing notions of identity. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my family for their encouragement throughout the process of writing this thesis. -

The Museum of Modern Art Celebrates Vienna's Rich

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART CELEBRATES VIENNA’S RICH CINEMATIC HISTORY WITH MAJOR COLLABORATIVE EXHIBITION Vienna Unveiled: A City in Cinema Is Held in Conjunction with Carnegie Hall’s Citywide Festival Vienna: City of Dreams, and Features Guest Appearances by VALIE EXPORT and Jem Cohen Vienna Unveiled: A City in Cinema February 27–April 20, 2014 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, January 29, 2014—In honor of the 50th anniversary of the Austrian Film Museum, Vienna, The Museum of Modern Art presents a major collaborative exhibition exploring Vienna as a city both real and mythic throughout the history of cinema. With additional contributions from the Filmarchiv Austria, the exhibition focuses on Austrian and German Jewish émigrés—including Max Ophuls, Erich von Stroheim, and Billy Wilder—as they look back on the city they left behind, as well as an international array of contemporary filmmakers and artists, such as Jem Cohen, VALIE EXPORT, Michael Haneke, Kurt Kren, Stanley Kubrick, Richard Linklater, Nicholas Roeg, and Ulrich Seidl, whose visions of Vienna reveal the powerful hold the city continues to exert over our collective unconscious. Vienna Unveiled: A City in Cinema is organized by Alexander Horwath, Director, Austrian Film Museum, Vienna, and Joshua Siegel, Associate Curator, Department of Film, MoMA, with special thanks to the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere. The exhibition is also held in conjunction with Vienna: City of Dreams, a citywide festival organized by Carnegie Hall. Spanning the late 19th to the early 21st centuries, from historical and romanticized images of the Austro-Hungarian empire to noir-tinged Cold War narratives, and from a breeding ground of anti- Semitism and European Fascism to a present-day center of artistic experimentation and socioeconomic stability, the exhibition features some 70 films. -

Titel Kino 3/2003

EXPORT-UNION OF GERMAN CINEMA 3/2003 AT LOCARNO MEIN NAME IST BACH & DAS WUNDER VON BERN Piazza Grande AT VENICE ROSENSTRASSE in Competition AT SAN SEBASTIAN SCHUSSANGST & SUPERTEX in Competition FOCUS ON Film Music in Germany Kino Martin Feifel, Katja Riemann (photo © Studio Hamburg) Martin Feifel, Katja GERMAN CINEMA KINO3/2003 4 focus on film music in germany DON’T SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER 14 directors’ portraits THE SUN IS AS MUCH MINE AS THE NIGHT A portrait of Fatih Akin 15 TURNING GENRE CINEMA UPSIDE DOWN A portrait of Nina Grosse 18 producer’s portrait LOOKING FOR A VISION A portrait of Bavaria Filmverleih- & Produktions GmbH 20 actress’ portrait BREAKING THE SPELL A portrait of Hannelore Elsner 22 KINO news in production 28 ABOUT A GIRL Catharina Deus 28 AGNES UND SEINE BRUEDER Oskar Roehler 29 DER CLOWN Sebastian Vigg 30 C(R)OOK Pepe Danquart 30 ERBSEN AUF HALB 6 Lars Buechel 31 LATTENKNALLER Sherry Hormann 32 MAEDCHEN MAEDCHEN II Peter Gersina 32 MARSEILLE Angela Schanelec 33 SAMS IN GEFAHR Ben Verbong 34 SOMMERBLITZE Nicos Ligouris 34 (T)RAUMSCHIFF SURPRISE – PERIODE 1 Michael "Bully" Herbig 35 DER UNTERGANG – HITLER UND DAS ENDE DES DRITTEN REICHES Oliver Hirschbiegel the 100 most significant german films (part 10) 40 WESTFRONT 1918 THE WESTERN FRONT 1918 Georg Wilhelm Pabst 41 DIE DREIGROSCHENOPER THE THREEPENNY OPERA Georg Wilhelm Pabst 42 ANGST ESSEN SEELE AUF FEAR EATS THE SOUL Rainer Werner Fassbinder 43 DER VERLORENE THE LOST ONE Peter Lorre new german films 44 V Don Schubert 45 7 BRUEDER 7 BROTHERS Sebastian Winkels -

We Need a Completely Different Kind of Courage.« Stefan Zweig – Farewell to Europe

»We need a completely different kind of courage.« Stefan Zweig – Farewell to Europe With his wife, Lotte, Stefan Zweig boarded the British passenger ship Scythia on the evening of 25 June 1940 and sailed from Liverpool to New York. Neither of them was ever to see Europe again. In February 1934 Zweig had moved out of his house in Salzburg. One year earlier Hitler had become chancellor of the German Reich, and life in Austria as well became characterized by the intolerance and hostility of those in power to the intellectual spirit. The first stop in Zweig’s exile was London, where he wrote his biography of Mary Stuart and the novel Ungeduld des Herzens (Beware of Pity). After divorcing his first wife in 1938, Zweig married his London secretary, Charlotte Elisabeth Altmann, a German emigrant, in September 1939. Both of them adopted British citizenship and lived for a few months in Bath before crossing the Atlantic. In February 1942, their suicide in the Brazilian city of Petrópolis made news around the world. The exhibition focuses on the scenario of parting: we look back on the lost »world of security« that Stefan Zweig described with great feeling in his me- Room 3 moirs. By this time the Belle Époque was already history, Europe was at war, On Saturday, 21 February 1942, one day before committing suicide with his wife, the paintings had been taken down from the walls, the carpets rolled up, and Stefan Zweig took the typescript of Schachnovelle (The Royal Game) to the post the packing cases were ready to go. -

Quarterly 1 · 2006

German Films Quarterly 1 · 2006 AT BERLIN In Competition ELEMENTARTEILCHEN by Oskar Roehler DER FREIE WILLE by Matthias Glasner REQUIEM by Hans-Christian Schmid PORTRAITS Gregor Schnitzler, Isabelle Stever, TANGRAM Film, Henry Huebchen SHOOTING STAR Johanna Wokalek SPECIAL REPORT Germans in Hollywood german films quarterly 1/2006 focus on 4 GERMANS IN HOLLYWOOD directors’ portraits 12 PASTA LA VISTA, BABY! A portrait of Gregor Schnitzler 14 FILMING AT EYE LEVEL A portrait of Isabelle Stever producer’s portrait 16 BLENDING TRADITION WITH INNOVATION A portrait of TANGRAM Filmproduktion actors’ portraits 18 GO FOR HUEBCHEN! BETWEEN MASTROIANNI AND BRANDO A portrait of Henry Huebchen 20 AT HOME ON STAGE AND SCREEN A portrait of Johanna Wokalek 22 news in production 28 AM LIMIT Pepe Danquart 28 DAS BABY MIT DEM GOLDZAHN Daniel Acht 29 DAS DOPPELTE LOTTCHEN Michael Schaack, Tobias Genkel 30 FC VENUS Ute Wieland 31 FUER DEN UNBEKANNTEN HUND Dominik Reding, Benjamin Reding 31 HELDIN Volker Schloendorff 32 LEBEN MIT HANNAH Erica von Moeller 33 LIEBESLEBEN Maria Schrader 34 MARIA AM WASSER Thomas Wendrich 35 SPECIAL Anno Saul 36 TANZ AM UFER DER TRAEUME Cosima Lange 36 TRIP TO ASIA – DIE SUCHE NACH DEM EINKLANG Thomas Grube new german films 38 3° KAELTER 3° COLDER (NEW DIRECTOR’S CUT) Florian Hoffmeister 39 12 TANGOS – ADIOS BUENOS AIRES Arne Birkenstock 40 89 MILLIMETER 89 MILLIMETRES Sebastian Heinzel 41 AFTER EFFECT Stephan Geene 42 BLACKOUT Maximilian Erlenwein 43 BUONANOTTE TOPOLINO BYE BYE BERLUSCONI! Jan Henrik Stahlberg 44 CON GAME Wolf -

Brigitte Hobmeier

WEISSE LILIEN Ein Film von Christian Frosch A | D | LUX | H 2007, 96 min KINOSTART: 29. August 2008 Verleih polyfilm Verleih 1050 Wien Margaretenstraße 78 T 581 39 00 20 F 581 39 00 39 www.polyfilm.at Pressebetreuung apomat* büro für kommunikation Andrea Pollach 0699/194 484 51 Mahnaz Tischeh 0699/119 022 57 [email protected] www.apomat.at WEISSE LILIEN – SILENT RESIDENT 2007 | A,D,LUX,H | 96 min | Deutsch | 35mm | Farbe | 1:2,35 CREDITS REGIE Christian Frosch KAMERA Busso von Müller SCHNITT Michael Palm TON Jörg Theil AUSSTATTUNG Giovanni Scribano KOSTÜM Alfred Mayerhofer KOMPONIST Andreas Ockert SOUNDDESIGN Michael Palm, Sebastian Schmidt TONMISCHUNG Olaf Mehl PRODUKTION Amour Fou Filmproduktion | Alexander Dumreicher-Ivanceanu und KGP Kranzelbinder Gabriele Production | Gabriele Kranzelbinder KOPRODUKTION DEUTSCHLAND Mediopolis, Alexander Ris, Jörg Rothe Neue Visionen Filmproduktion, Matthias Mücke und Torsten Frehse Weltfilm, Kristina Konrad und Christian Frosch KOPRODUKTION UNGARN Eurofilm Studio, Péter Miskolczi KOPRODUKTION LUXEMBOURG Minotaurus Film, Bady Minck WELTVERTRIEB Bavaria Film International FÖRDERUNGEN ÖFI (Österreichisches Filminstitut), FFW (Filmfonds Wien), ORF (Film/Fernsehabkommen), Medienboard Berlin-Brandenburg, Filmfund Luxembourg, MDM (Mitteldeutsche Medienförderung), Motion Picture Public Foundation of Hungary, Ministerium für Bildung und Kultur der Republik Ungarn, MEDIA Programm DARSTELLERINNEN und DARSTELLER Brigitte Hobmeier, Martin Wuttke, Johanna Wokalek, Erni Mangold, Walfriede Schmitt, Xaver Hutter,