JULIANE KÖHLER Lilly Wust [“Aimée”]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Hammond Jr

HAMMOND, Charles Henry Jr. 1 UNIVERSITY FACULTY CURRICULUM VITAE I. Personal Information Charles Hammond Jr. Professor of German, With Tenure Department of Modern Foreign Languages 427D Andy Holt Humanities Building University of Tennessee at Martin Martin, TN 38237 II. Educational Credentials Ph.D. in German Literature 2006 University of California, Irvine Dissertation Title: Blind Alleys: Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Oscar Wilde and the Problem of Aestheticism M.A. in German Literature 1998 University of California, Irvine Bachelor of Science in the Language Arts 1993 Georgetown University Major field of study: German Minor field of study: Italian III. Employment History / Teaching Professor (tenured) 2017-Present Department of Modern Foreign Languages University of Tennessee at Martin Associate Professor (tenured) 2012-2017 Department of Modern Foreign Languages University of Tennessee at Martin I teach German courses on German language, literature and culture at all levels, monitor a language laboratory, advise and recruit students. In addition, I organize the 10-day travel- study to Braunschweig and accompany students on that trip every summer in order to provide supervision and guidance. Adjunct Instructor of Martial Arts 2014-Present Department of Health and Human Performance University of Tennessee at Martin HAMMOND, Charles Henry Jr. 2 I teach two courses every semester (PACT 119-01 and 119-02) in the art of Shotokan Karate. I was originally hired to teach just one section, but it filled up and a second was opened, which promptly filled up, as well. Since that time, the enrollment has reflected the widespread enthusiasm for the course at UT Martin. Assistant Professor (tenured) 2006-2012 Department of Modern Foreign Languages University of Tennessee at Martin Assistant Professor (3-year term appointment) 2005-2006 Department of Modern Foreign Languages University of Tennessee at Martin For responsibilities, see description above. -

Redalyc.PERIODISMO Y MEMORIA DE LAS VÍCTIMAS DE LA SHOAH

Razón y Palabra ISSN: 1605-4806 [email protected] Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey México Schryver Kurtz, Adriana PERIODISMO Y MEMORIA DE LAS VÍCTIMAS DE LA SHOAH Razón y Palabra, vol. 14, núm. 70, noviembre-enero, 2009, pp. 1-15 Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey Estado de México, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=199520478032 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto RAZÓN Y PALABRA Primera Revista Electrónica en América Latina Especializada en Comunicación www.razonypalabra.org.mx PERIODISMO Y MEMORIA DE LAS VÍCTIMAS DE LA SHOAH Adriana Schryver Kurtz 1 RESUMEN Irónicamente, el periodismo, como parte noble del aparato mediático de la sociedad de consumo contemporánea, hoy representa una perspectiva real de rescate de la memoria de las vidas devastadas por la Shoah, uno de los eventos históricos más aterradores del siglo y que Theodor Adorno nombró, con pertinencia, de “La Era de las Catástrofes”. Acusada por Walter Benjamín de ser detonadora de la muerte de la narrativa, la prensa – a partir de una simple nota publicada el 22 de septiembre de 1981, en Der Tagesspiegel, vehículo de la República Federal Alemana – acabaría por develar las memorias aparentemente perdidas de la “judía” Felice Rahel Schragenheim, a través del valiente testimonio de la “aria” Elisabeth Wust, con quien viviría una tórrida historia de amor en 1943, bajo los efectos de la violencia política antisemita berlinesa, capital alemana del III Reich. -

2002 Illinois Shakespeare Festival Program School of Theatre and Dance Illinois State University

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Illinois Shakespeare Festival Fine Arts Summer 2002 2002 Illinois Shakespeare Festival Program School of Theatre and Dance Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/isf Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation School of Theatre and Dance, "2002 Illinois Shakespeare Festival Program" (2002). Illinois Shakespeare Festival. 28. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/isf/28 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Fine Arts at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Illinois Shakespeare Festival by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I LLINOIS SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL Folio A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM ROMEO & JULIET THE MERCHANT OF VENICE 2 5rhSeason THE THEATRE AT EWING MANOR - 2002 "A bed, a bed, my kingdom for a bed ... " You'll fall in love with our beds and a whole lot more at the Hampton Inn Bloomington-Normal. Guaranteed. With complimentary breakfast buffet, free local calls, an outdoor heated pool, and your choice of smoking or non-smoking rooms, plus the opportunity to earn Hilton HHonors hotel points and airline miles. All backed by our 100% Satisfaction Guarantee. If you're not completely satisfied, your night's stay is free. Hampton Inn Bloomington/Normal 604 ½ I.A.A. Drive Bloomington, IL 61701 The closest hotel to the Festival. For reservations call (309) 662-2800 or 1-800 HAMPTON For cellular reservations, call #INN. ~~ ~ 6 o/ ILLINOIS SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL 20oi A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE JUNE 19, 21, 27, 29, JULY 5, 7, 13, 16, 20, 21, 26, 27, AUGUST I, 4, 7, IO czSo ROMEO AND JULIET BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE JUNE 20, 22, 28, 30, JULY 6, 14, 18, 20, 24, 28, 31, AUGUST 2, 8 czSo THE MERCHANT OF VENICE BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE JULY II, 12, 17, 19, 23, 25, 27, 30, AUGUST 3, 6, 9 EWING MANOR, BLOOMINGTON • WESTHOFF THEATRE, NORMAL CALVIN MAcLEAN FERGUS G. -

Wahlen Beteiligten, Vorab Den Bügerinitia- Tigen Form Erholungsmöglichkei- Kategorie „Zugeständnisse“, Soll- Rie Die Qual Der Wahl Ein Bisschen Was Versteht Horst S

Die Stadtteilzeitung Ihre Zeitung für Schöneberg - Friedenau - Steglitz Zeitung für bürgerschaftliches Engagement und Stadtteilkultur Ausgabe Nr. 85 - Oktober 2011 www.stadtteilzeitung.nbhs.de Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, L Schule im Kiez wenn Sie gedacht haben, mit Die Qual der Wahl der Ausübung Ihrer staatsbür- gerlichen Pflicht hätte sich die oder Lust auf Neues Sache erledigt - nun - so einfach ist das nicht. Nach der Wahl Das neue Schuljahr hat begonnen gibt es Gewinner und Verlierer; und sowohl die Erstklässler als richtig! Aber manchmal sind auch die Schüler, die auf eine wei- die Gewinner die Verlierer, be- terführende Schule gewechselt ziehungsweise umgekehrt. Neh- sind, haben ihren Platz gefunden. men wir unseren Bezirk Tem- pelhof-Schöneberg. Wie Sie den Nun ist bald der nächste Jahrgang an der Reihe und für die Eltern vorläufigen Ergebnissen, die stellt sich das Problem, eine geeig- wir für Sie auf Seite 2 für Schö- nete Schule zu finden. Und das neberg zusammengestellt ha- wird nach den vielen Schulrefor- ben, entnehmen können, hat bei men der letzten Jahre immer der Wahl zur BVV Tempelhof- schwieriger. Schöneberg die CDU die meis- Grundschule mit jahrgangsüber- ten Stimmen erhalten. Trotz- greifendem Unterricht, oder doch dem wird aller Voraussicht nach nicht, Integrationsschule oder die SPD den nächsten Bürger- jetzt schon spezielle Förderung meister, bzw. Bürgermeisterin von Interessen? Gymnasium oder stellen. Eine Zählgemeinschaft Schön übersichtlich Foto: Hartmut Becker Sekundarschule, zusammen mit mit den Grünen kann das er- den Freunden oder zukunftsorien- L möglichen. Und so könnte es Neues vom Gleisdreieck von Sigrid Wiegand tierte Schwerpunkte? Wo beste- auch anderen Bezirken ergehen. hen die besten Möglichkeiten, Das Szenario hat eine Gruppie- angenommen zu werden? Fast rung namens „Donnerstags- nichts ist mehr wie es war, wie wir kreis“ innerhalb der Landes-SPD Auf Betonpisten durch die Wiesen Eltern es kennen oder kannten. -

Spaziergang Im Grunewald - S

Ein Projekt der AUSGABE 02/2020 IN SCHMARGENDORF UNTERWEGS GLEICH NEBENAN: DIE FU BERLIN UND IHRE BAUWERKE - S. 2 NATUR SO NAH: SPAZIERGANG IM GRUNEWALD - S. 3 PROMINENTE SCHMARGEN- DORFERINNEN: „AIMÉE UND JAGUAR“ - S. 4 - Anzeige - - Anzeige - In Schmargendorf unterwegs Seite 2 AUSGABE 02/2020 FORSCHUNG UND LEHRE ZWISCHEN DAHLEMER VILLEN Ein Spaziergang über das Gelände der Freien Universität Berlin Foto: Christian Kruppa Christian Foto: © SCHMARGENDORF – PARADIES FÜR SPAZIERGÄNGER Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, Foto: Christian Kruppa Christian Foto: © es sind schwierige Zeiten. Der Kampf gegen geschichte zu entdecken: das weite Gelände der die weitere Ausbreitung des neuen Coronavirus FU Berlin in Dahlem oder den Grunewald, der hat Berlin immer noch fest im Griff. Zwar gab in den Jahren der Teilung Berlins der wichtigste Nur wenige Hundert Meter entfernt vom ten Stadtteil Dahlem. Die Blockade Westber- es in den letzten Wochen einige Lockerungen, Naturzugang für die Einwohner in der West- Schmargendorfer Zentrum an der Breiten lins durch die Sowjetunion ab dem Sommer aber noch weiß niemand, wie sich das Stadtle- hälfte der Stadt war. Straße beginnt das Gelände der Freien Uni- 1948 beschleunigte die Planung, und so kam ben in den Sommermonaten entwickeln wird, versität Berlin, jener deutschen Hochschule, es bereits im Dezember 1948 zur Gründung. welche Verbote weiterhin gelten oder welche Wie Sie Ihren Lieblingsläden oder Stammres- die nicht nur die Stadt Berlin, sondern auch neuen Maßnahmen eventuell ergriffen werden taurants im Kiez auch in diesen Zeiten etwas die Bundesrepublik in den Jahren der deut- Den Hauptteil des Campus stellte in den An- müssen. Auf jeden Fall aber ist es erst einmal Gutes tun und so dazu beitragen können, dass schen Teilung massiv geprägt hat. -

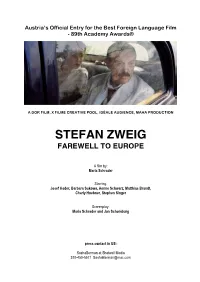

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

Love Between Women in the Narrative of the Holocaust

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2015 Unacknowledged Victims: Love between Women in the Narrative of the Holocaust. An Analysis of Memoirs, Novels, Film and Public Memorials Isabel Meusen University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Meusen, I.(2015). Unacknowledged Victims: Love between Women in the Narrative of the Holocaust. An Analysis of Memoirs, Novels, Film and Public Memorials. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3082 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Unacknowledged Victims: Love between Women in the Narrative of the Holocaust. An Analysis of Memoirs, Novels, Film and Public Memorials by Isabel Meusen Bachelor of Arts Ruhr-Universität Bochum, 2007 Master of Arts Ruhr-Universität Bochum, 2011 Master of Arts University of South Carolina, 2011 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: Agnes Mueller, Major Professor Yvonne Ivory, Committee Member Federica Clementi, Committee Member Laura Woliver, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Isabel Meusen, 2015 All Rights reserved. ii Dedication Without Megan M. Howard this dissertation wouldn’t have made it out of the petri dish. Words will never be enough to express how I feel. -

German Films Quarterly 2 · 2004

German Films Quarterly 2 · 2004 AT CANNES In Competition DIE FETTEN JAHRE SIND VORBEI by Hans Weingartner FULFILLING EXPECTATIONS Interview with new FFA CEO Peter Dinges GERMAN FILM AWARD … and the nominees are … SPECIAL REPORT 50 Years Export-Union of German Cinema German Films and IN THE OFFICIAL PROGRAM OF THE In Competition In Competition (shorts) In Competition Out of Competition Die Fetten Der Tropical Salvador Jahre sind Schwimmer Malady Allende vorbei The Swimmer by Apichatpong by Patricio Guzman by Klaus Huettmann Weerasethakul The Edukators German co-producer: by Hans Weingartner Producer: German co-producer: CV Films/Berlin B & T Film/Berlin Thoke + Moebius Film/Berlin German producer: World Sales: y3/Berlin Celluloid Dreams/Paris World Sales: Celluloid Dreams/Paris Credits not contractual Co-Productions Cannes Film Festival Un Certain Regard Un Certain Regard Un Certain Regard Directors’ Fortnight Marseille Hotel Whisky Charlotte by Angela Schanelec by Jessica Hausner by Juan Pablo Rebella by Ulrike von Ribbeck & Pablo Stoll Producer: German co-producer: Producer: Schramm Film/Berlin Essential Film/Berlin German co-producer: Deutsche Film- & Fernseh- World Sales: Pandora Film/Cologne akademie (dffb)/Berlin The Coproduction Office/Paris World Sales: Bavaria Film International/ Geiselgasteig german films quarterly 2/2004 6 focus on 50 YEARS EXPORT-UNION OF GERMAN CINEMA 22 interview with Peter Dinges FULFILLING EXPECTATIONS directors’ portraits 24 THE VISIONARY A portrait of Achim von Borries 25 RISKING GREAT EMOTIONS A portrait of Vanessa Jopp 28 producers’ portrait FILMMAKING SHOULD BE FUN A portrait of Avista Film 30 actor’s portrait BORN TO ACT A portrait of Moritz Bleibtreu 32 news in production 38 BERGKRISTALL ROCK CRYSTAL Joseph Vilsmaier 38 DAS BLUT DER TEMPLER THE BLOOD OF THE TEMPLARS Florian Baxmeyer 39 BRUDERMORD FRATRICIDE Yilmaz Arslan 40 DIE DALTONS VS. -

German Videos - (Last Update December 5, 2019) Use the Find Function to Search This List

German Videos - (last update December 5, 2019) Use the Find function to search this list Aguirre, The Wrath of God Director: Werner Herzog with Klaus Kinski. 1972, 94 minutes, German with English subtitles. A band of Spanish conquistadors travels into the Amazon jungle searching for the legendary city of El Dorado, but their leader’s obsessions soon turn to madness.LLC Library CALL NO. GR 009 Aimée and Jaguar DVD CALL NO. GR 132 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul Director: Rainer Werner Fassbinder. with Brigitte Mira, El Edi Ben Salem. 1974, 94 minutes, German with English subtitles. A widowed German cleaning lady in her 60s, over the objections of her friends and family, marries an Arab mechanic half her age in this engrossing drama. LLC Library CALL NO. GR 077 All Quiet on the Western Front DVD CALL NO. GR 134 A/B Alles Gute (chapters 1 – 4) CALL NO. GR 034-1 Alles Gute (chapters 13 – 16) CALL NO. GR 034-4 Alles Gute (chapters 17 – 20) CALL NO. GR 034-5 Alles Gute (chapters 21 – 24) CALL NO. GR 034-6 Alles Gute (chapters 25 – 26) CALL NO. GR 034-7 Alles Gute (chapters 9 – 12) CALL NO. GR 034-3 Alpen – see Berlin see Berlin Deutsche Welle – Schauplatz Deutschland, 10-08-91. [ Opening missing ], German with English subtitles. LLC Library Alpine Austria – The Power of Tradition LLC Library CALL NO. GR 044 Amerikaner, Ein – see Was heißt heir Deutsch? LLC Library Annette von Droste-Hülshoff CALL NO. GR 120 Art of the Middle Ages 1992 Studio Quart, about 30 minutes. -

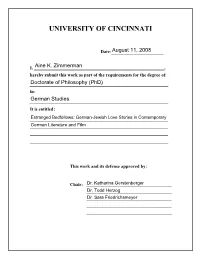

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Estranged Bedfellows: German-Jewish Love Stories in Contemporary German Literature and Film A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies at the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of German Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences 2008 by Aine K. Zimmerman Master of Arts, University of Washington, 2000 Bachelor of Arts, University of Cincinnati, 1997 Committee Chair: Professor Katharina Gerstenberger Abstract This dissertation is a survey and analysis of German-Jewish love stories, defined as romantic entanglements between Jewish and non-Jewish German characters, in German literature and film from the 1980s to the 21st century. Breaking a long-standing taboo on German-Jewish relationships since the Holocaust, there is a spate of such love stories from the late 1980s onward. These works bring together members of these estranged groups to spin out the consequences, and this project investigates them as case studies that imagine and comment on German-Jewish relations today. Post-Holocaust relations between Jews and non-Jewish Germans have often been described as a negative symbiosis. The works in Chapter One (Rubinsteins Versteigerung, “Aus Dresden ein Brief,” Eine Liebe aus nichts, and Abschied von Jerusalem) reinforce this description, as the German-Jewish couples are connected yet divided by the legacy of the Holocaust. -

The Museum of Modern Art Celebrates Vienna's Rich

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART CELEBRATES VIENNA’S RICH CINEMATIC HISTORY WITH MAJOR COLLABORATIVE EXHIBITION Vienna Unveiled: A City in Cinema Is Held in Conjunction with Carnegie Hall’s Citywide Festival Vienna: City of Dreams, and Features Guest Appearances by VALIE EXPORT and Jem Cohen Vienna Unveiled: A City in Cinema February 27–April 20, 2014 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, January 29, 2014—In honor of the 50th anniversary of the Austrian Film Museum, Vienna, The Museum of Modern Art presents a major collaborative exhibition exploring Vienna as a city both real and mythic throughout the history of cinema. With additional contributions from the Filmarchiv Austria, the exhibition focuses on Austrian and German Jewish émigrés—including Max Ophuls, Erich von Stroheim, and Billy Wilder—as they look back on the city they left behind, as well as an international array of contemporary filmmakers and artists, such as Jem Cohen, VALIE EXPORT, Michael Haneke, Kurt Kren, Stanley Kubrick, Richard Linklater, Nicholas Roeg, and Ulrich Seidl, whose visions of Vienna reveal the powerful hold the city continues to exert over our collective unconscious. Vienna Unveiled: A City in Cinema is organized by Alexander Horwath, Director, Austrian Film Museum, Vienna, and Joshua Siegel, Associate Curator, Department of Film, MoMA, with special thanks to the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere. The exhibition is also held in conjunction with Vienna: City of Dreams, a citywide festival organized by Carnegie Hall. Spanning the late 19th to the early 21st centuries, from historical and romanticized images of the Austro-Hungarian empire to noir-tinged Cold War narratives, and from a breeding ground of anti- Semitism and European Fascism to a present-day center of artistic experimentation and socioeconomic stability, the exhibition features some 70 films. -

Titel Kino 4/2000 Nr. 1U.2

EXPORT-UNION OF GERMAN CINEMA 4/2000 Special Report: TRAINING THE NEXT GENERATION – Film Schools In Germany ”THE TANGO DANCER“: Portrait of Jeanine Meerapfel Selling German Films: CINE INTERNATIONAL & KINOWELT INTERNATIONAL Kino Scene from:“A BUNDLE OF JOY” GERMAN CINEMA Launched at MIFED 2000 a new label of Bavaria Film International Further info at www.bavaria-film-international.de www. german- cinema. de/ FILMS.INFORMATION ON GERMAN now with links to international festivals! GERMAN CINEMA Export-Union des Deutschen Films GmbH · Tuerkenstrasse 93 · D-80799 München phone +49-89-3900 9 5 · fax +49-89-3952 2 3 · email: [email protected] KINO 4/2000 6 Training The Next Generation 33 Soweit die Füße tragen Film Schools in Germany Hardy Martins 34 Vaya Con Dios 15 The Tango Dancer Zoltan Spirandelli Portrait of Jeanine Meerapfel 34 Vera Brühne Hark Bohm 16 Pursuing The Exceptional 35 Vill Passiert In The Everyday Wim Wenders Portrait of Hans-Christian Schmid 18 Then She Makes Her Pitch Cine International 36 German Classics 20 On Top Of The Kinowelt 36 Abwärts Kinowelt International OUT OF ORDER Carl Schenkel 21 The Teamworx Player 37 Die Artisten in der Zirkuskuppel: teamWorx Production Company ratlos THE ARTISTS UNDER THE BIG TOP: 24 KINO news PERPLEXED Alexander Kluge 38 Ehe im Schatten MARRIAGE IN THE SHADOW 28 In Production Kurt Maetzig 39 Harlis 28 B-52 Robert van Ackeren Hartmut Bitomsky 40 Karbid und Sauerampfer 28 Die Champions CARBIDE AND SORREL Christoph Hübner Frank Beyer 29 Julietta 41 Martha Christoph Stark Rainer Werner Fassbinder 30 Königskinder Anne Wild 30 Mein langsames Leben Angela Schanelec 31 Nancy und Frank Wolf Gremm 32 Null Uhr Zwölf Bernd-Michael Lade 32 Das Sams Ben Verbong CONTENTS 50 Kleine Kreise 42 New German Films CIRCLING Jakob Hilpert 42 Das Bankett 51 Liebe nach Mitternacht THE BANQUET MIDNIGHT LOVE Holger Jancke, Olaf Jacobs Harald Leipnitz 43 Doppelpack 52 Liebesluder DOUBLE PACK A BUNDLE OF JOY Matthias Lehmann Detlev W.