P. Vasundhara Rao.Cdr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Untimely Meditation: Nietzsche Et Cetera1

PERFORMANCE PHILOSOPHY UNTIMELY MEDITATION: NIETZSCHE ET CETERA1 ARNO BÖHLER UNIVERSITY OF VIENNA Translation from German to English: Mirko Wittwar Video documentation: http://homepage.univie.ac.at/arno.boehler/php/?p=9078 Lecture-Performance: 29 November 2015—Philosophy On Stage #4—Tanzquartier Wien HALLE G FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE: Nicholas Ofczarek CHORUS: Jeanne Marie Bertram, Max Gindorff, Maria Huber, René Peckl, Sophie Reiml TEXT: Arno Böhler SPACE DESIGN: Hans Hoffer PERFORMANCE PHILOSOPHY VOL 3, NO 3 (2017):631–649 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21476/PP.2017.33178 ISSN 2057-7176 ACTOR A “[T]rue philosophy, as a philosophy of the future, is no more historical than it is eternal: it must be untimely, always untimely” (Deleuze 2001, 72). FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE We are told to accept the real. But the “so called real” exists according to the logic of power. It is that reality which has been generated and established from the point of view of power. Let us not deceive ourselves. This, the point of view of power, is our first nature. We do not only inherit it. It commands us to behave in conformity with it. It wants us to be agents of its perspective on our lives. That is why it tells us to become timely. But philosophical thought is untimely! It is always and again and again newly untimely. It turns against its time—in favour of a coming time which demands to be considered beforehand to make it come. Philosophical thought is this turn of the times when it starts resisting that what it has told so far. -

Buddhist” Reading of Shakespeare

UNIWERSYTET ZIELONOGÓRSKI IN GREMIUM 14/2020 Studia nad Historią, Kulturą i Polityką DOI 10.34768/ig.vi14.301 ISSN 1899-2722 s. 193-205 Antonio Salvati Universitá degli Studi della Campania „Luigi Vanvitelli” ORCID: 0000-0002-4982-3409 GIUSEPPE DE LORENZO AND HIS “BUDDHIST” READING OF SHAKESPEARE The road to overcoming pain lies in pain itself The following assumption is one of the pivotal points of Giuseppe De Lorenzo’s reflection on pain: “Solamente l’umanità può attingere dalla visione del dolore la forza per redimersi dal circolo dalla vita”,1 as he wrote in the first edition (1904) of India e Buddhismo antico in affinity with Hölderlin’s verses: “Nah ist/Und schwer zu fassen der Gott./Wo aber Gefahr ist, wächst/Das Rettende auch”,2 and anticipating Giuseppe Rensi who wrote in 1937 in his Frammenti: “La natura dell’universo la conosce non l’uomo sano, ricco, fortunato, felice, ma l’uomo percorso dalle malattie, dalle sventure, dalla povertà, dalle persecuzioni. Solo costui sa veramente che cos’è il mondo. Solo egli lo vede. Solo a lui i dolori che subisce danno la vista”.3 If pain really is this anexperience in which man questions himself and acquires the wisdom to free himself from the state of suffering it is clear why suffering “seems to be particularly essential to the nature of man […] Suffering seems to belong to man’s 1 “Only humanity can draw the strength to redeem itself from the circle of life through the vision of pain”. Giuseppe De Lorenzo (Lagonegro 1871-Naples 1957) was a geologist, a translator of Buddhist texts and Schopenhauer, and a great reader of Shakespeare, Byron and Leopardi. -

Vedanta in the West: Past, Present, and Future

Vedanta in the West: Past, Present, and Future Swami Chetanananda What Is Vedanta? Vedanta is the culmination of all knowledge, the sacred wisdom of the Indian sages, the sum of the transcendental experiences of the seers of Truth. It is the essence, or the conclusion, of the scriptures known as the Vedas. Because the Upanishads come at the end of the Vedas they are collectively referred to as Vedanta. Literally, Veda means "knowledge" and anta means "end." Vedanta is a vast subject. Its scriptures have been evolving for the last five thousand years. The three basic scriptures of Vedanta are the Upanishads (the revealed truths), the Brahma Sutras (the reasoned truths), and the Bhagavad Gita (the practical truths). Some Teachings from Vedanta Here are some teachings from the Upanishads: “Arise! Awake! Approach the great teachers and learn.” “Aham Brahmasmi.” [I am Brahman.] “Tawamasi.” [Thou art That.] “Sarvam khalu idam Brahma.” [Verily, everything is Brahman.] “Whatever exists in this changing universe is enveloped by God.” “If a man knows Atman here, he then aains the true goal of life.” “Om is the bow; the Atman is the arrow; Brahman is said to be the mark. It is to be struck by an undistracted mind.” “He who knows Brahman becomes Brahman.” “His hands and feet are everywhere. His eyes, heads, and mouths are everywhere. His ears are everywhere. He pervades everything in the universe.” “Speak the truth. Practise dharma. Do not neglect your study of the Vedas. Treat your mother as God. Treat your father as God. Treat your teacher as God. -

03. Nietzsche's Works.Pdf

Nietzsche & Asian Philosophy Nietzsche’s Works Main Published Works in Chronological Order with Bibliography of English Translations Die Geburt der Tragödie aus dem Geiste der Musik (The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music) (1872) The Birth of Tragedy. Translated by Walter Kaufmann. Published with The Case of Wagner. New York: Vintage, 1966. The Birth of Tragedy and Other Writings. Translated by Ronald Speirs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen (Untimely Meditations, Untimely Reflections, Thoughts Out of Season) I. David Strauss, der Bekenner und der Schriftsteller (David Strauss, The Confessor and the Writer) (1873) II. Vom Nützen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben (On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life) (1874) III. Schopenhauer als Erzieher (Schopenhauer as Educator) (1874) IV. Richard Wagner in Bayreuth (1876) Untimely Meditations. Translated by R.J. Hollingdale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983. Menschliches, Allzumenschliches: ein Buch für freie Geister (Human, All Too Human, a Book for Free Spirits) (1878) Human, All Too Human. Translated by R.J. Hollingdale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986. Two Sequels to Human, All Too Human: Vermischte Meinungen und Sprüche (Assorted Opinions and Sayings) (1879) Der Wanderer und sein Schatten (The Wanderer and his Shadow) (1880) Human, All Too Human II. Translated by R.J. Hollingdale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986. Die Morgenröte: Gedanken über die moralischen Vorurteile (The Dawn, Daybreak, Sunrise: Thoughts on Moral Prejudices) (1881) Daybreak: Thoughts on the Prejudices of Morality. Translated by R.J. Hollingdale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982. Die fröhliche Wissenschaft (The Gay Science, The Joyful Wisdom, The Joyful Science) (Books I- IV 1882) (Book V 1887) The Gay Science. -

Traces of Friedrich Nietzsche's Philosophy

Traces of Friedrich Nietzsche’s Philosophy in Scandinavian Literature Crina LEON* Key-words: Scandinavian literature, Nietzschean philosophy, Georg Brandes, August Strindberg, Knut Hamsun 1. Introduction. The Role of the Danish Critic Georg Brandes The age of Friedrich Nietzsche in Scandinavia came after the age of Émile Zola, to whom Scandinavian writers such as Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg were indebted with a view to naturalistic ideas and attitudes. Friedrich Nietzsche appears to me the most interesting writer in German literature at the present time. Though little known even in his own country, he is a thinker of a high order, who fully deserves to be studied, discussed, contested and mastered (Brandes 1915: 1). This is what the Danish critic Georg Brandes asserted in his long Essay on Aristocratic Radicalism, which was published in August 1889 in the periodical Tilskueren from Copenhagen, and this is the moment when Nietzsche became to be known not only in Scandinavia but also in other European countries. The Essay on Aristocratic Radicalism was the first study of any length to be devoted, in the whole of Europe, to this man, whose name has since flown round the world and is at this moment one of the most famous among our contemporaries (Ibidem: 59), wrote Brandes ten years later. The term Aristocratic Radicalism had been previously used by the Danish critic in a letter he wrote to Nietzsche himself, from Copenhagen on 26 November 1887: …a new and original spirit breathes to me from your books […] I find much that harmonizes with my own ideas and sympathies, the depreciation of the ascetic ideals and the profound disgust with democratic mediocrity, your aristocratic radicalism […] In spite of your universality you are very German in your mode of thinking and writing (Ibidem: 63). -

Scattered Thoughts on Trauma and Memory*

Scattered thoughts on trauma and memory* ** Paolo Giuganino Abstract. This paper examines, from a personal and clinician's perspective, the interrelation between trauma and memory. The author recalls his autobiographical memories and experiences on this two concepts by linking them to other authors thoughts. On the theme of trauma, the author underlines how the Holocaust- Shoah has been the trauma par excellence of the twentieth century by quoting several writing starting from Rudolf Höss’s memoirs, Nazi lieutenant colonel of Auschwitz, to the same book’s foreword written by Primo Levi, as well as many other authors such as Vasilij Grossman and Amos Oz. The author stresses the distortion of German language operated by Nazism and highlights the role played by the occult, mythological and mystical traditions in structuring the Third Reich,particularly in the SS organization system and pursuit for a pure “Aryan race”. Moreover, the author highlights how Ferenczi's contributions added to the developments of the concept of trauma through Luis Martin-Cabré exploration and detailed study of the author’s psychoanalytic thought. Keywords: Trauma, memory, testimony, Holocaust, Shoah, survivors, state violence, forgiveness, Höss, Primo Levi, Karl Jaspers, Martin Heidegger, Vasilij Grossman, Amos Oz, Ferenczi, Freud, Luis-Martin Cabré. In memory of Gino Giuganino (1913-1949). A mountaineer and partisan from Turin. A righteous of the Italian Jewish community and honoured with a gold medal for having helped many victims of persecution to cross over into Switzerland saving them from certain death. To the Stuck N. 174517, i.e. Primo Levi To: «Paola Pakitz / Cantante de Operetta / Fja de Arone / De el ghetto de Cracovia /Fatta savon / Per ordine del Fuhrer / Morta a Mauthausen» (Carolus L. -

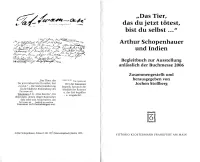

"Das Tier, Das Dujetzttötest, Bist Du Selbst Arthurschopenhauer Und

"Das Tier, das du jetzt tötest, bist du selbst Arthur Schopenhauer 4 und Indien Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung anlässlich der Buchmesse 2006 Zusammengestellt und "Das Thier, das Carica p 80 Tat-twam-asi herausgegeben von Du jetzt tödtest bist Du selbst, bist Wer das Tatgumes es - Jochen Stollberg jetzt." Die Seelenwanderung begreift, hat auch die ist die bildliche Einkleidung des Idealität des Raumes (Tat twam asi) u. der Zeit begriffen Tatoumes d. h. "Dies bist Du", für - u. umgekehrt. diejenigen, denen obiger Kantischer Satz oder sein Aequivalent, das Tat twam asi fasslich zu machen Tatoumes nicht beizubringen war. Arthur Schopenhauer, Foliant 2, Bi. 193r [Manuskriptbuchl Berlin 1826 VITTORIO KLOSTERMANN FRANKFURT AM MAIN Inhalt Klaus Ring Zum Geleit Matthias Koßler Grußwort Jochen Stollberg Arthur Schopenhauers Annäherung an die indische Welt 5 Urs App OUM - das erste Wort von Schopenhauers Lieblingsbuch 37 Urs App NICHTS - das letzte Wort von Schopenhauers Hauptwerk 51 Douglas L. Berger Erbschaften einer philosophischen Begegnung 61 Stephan Atzert Nirvana und Maya bei Schopenhauer 79 Heiner Feldhoff Und dann und wann ein weiser Elefant - Über Paul Deussens "Erinnerungen Indien" 85 Michael Gerhard Paul Deussen - Eine deutsch-indische Geistesbeziehung 101 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Arati Barua verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek of in India - Deutschen detaillierte bibliographische Daten Re-discovery Schopenhauer Nationalbibliographie; of the work and of sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Founding membership Indian branch of Schopenhauer Society 119 Thomas Frankfurter Bibliotheksschriften Regehly Schopenhauer und Siddharta 135 Herausgegeben von der Gesellschaft der Freunde der Stadt- und Universitätsbibliothek Frankfurt am Main e. -

Siddhartha's Smile: Schopenhauer, Hesse, Nietzsche

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Fall 2015 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Fall 2015 Siddhartha's Smile: Schopenhauer, Hesse, Nietzsche Benjamin Dillon Schluter Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2015 Part of the Continental Philosophy Commons, and the German Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Schluter, Benjamin Dillon, "Siddhartha's Smile: Schopenhauer, Hesse, Nietzsche" (2015). Senior Projects Fall 2015. 42. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_f2015/42 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Siddhartha’s Smile: Schopenhauer, Hesse, Nietzsche Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies and The Division of Languages and Literature of Bard College by Benjamin Dillon Schluter Annandale-on-Hudson, New York December 2015 Acknowledgments Mom: This work grew out of our conversations and is dedicated to you. Thank you for being the Nietzsche, or at least the Eckhart Tolle, to my ‘Schopenschluter.’ Dad: You footed the bill and never batted an eyelash about it. May this work show you my appreciation, or maybe just that I took it all seriously. -

Japanese Buddhism in Austria

Journal of Religion in Japan 10 (2021) 222–242 brill.com/jrj Japanese Buddhism in Austria Lukas Pokorny | orcid: 0000-0002-3498-0612 University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria [email protected] Abstract Drawing on archival research and interview data, this paper discusses the historical development as well as the present configuration of the Japanese Buddhist panorama in Austria, which includes Zen, Pure Land, and Nichiren Buddhism. It traces the early beginnings, highlights the key stages and activities in the expansion process, and sheds light on both denominational complexity and international entanglement. Fifteen years before any other European country (Portugal in 1998; Italy in 2000), Austria for- mally acknowledged Buddhism as a legally recognised religious society in 1983. Hence, the paper also explores the larger organisational context of the Österreichische Bud- dhistische Religionsgesellschaft (Austrian Buddhist Religious Society) with a focus on its Japanese Buddhist actors. Additionally, it briefly outlines the non-Buddhist Japanese religious landscape in Austria. Keywords Japanese Buddhism – Austria – Zen – Nichirenism – Pure Land Buddhism 1 A Brief Historical Panorama The humble beginnings of Buddhism in Austria go back to Vienna-based Karl Eugen Neumann (1865–1915), who, inspired by his readings of Arthur Schopen- hauer (1788–1860), like many others after him, turned to Buddhism in 1884. A trained Indologist with a doctoral degree from the University of Leipzig (1891), his translations from the Pāli Canon posthumously gained seminal sta- tus within the nascent Austrian Buddhist community over the next decades. His knowledge of (Indian) Mahāyāna thought was sparse and his assessment thereof was polemically negative (Hecker 1986: 109–111). -

The Looping Journey of Buddhism: from India to India

Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) Vol-2, Issue-9, 2016 ISSN: 2454-1362, http://www.onlinejournal.in The Looping Journey of Buddhism: From India To India Jyoti Gajbhiye Former Lecturer in Yashwant Rao Chawhan Open University. Abstract: This research paper aims to show how were situated along the Indus valley in Punjab and Buddhism rose and fell in India, with India Sindh. retaining its unique position as the country of birth Around 2000 BC, the Aarya travelers and invaders for Buddhism. The paper refers to the notion that came to India. The native people who were the native people of India were primarily Buddhist. Dravidian, were systematically subdued and It also examines how Buddhism was affected by defeated. various socio-religious factors. It follows how They made their own culture called “vedik Buddhism had spread all over the world and again Sanskriti”. Their beliefs lay in elements such Yajna came back to India with the efforts of many social (sacred fire) and other such rituals. During workers, monks, scholars, travelers, kings and Buddha’s time there were two cultures “Shraman religious figures combined. It examines the Sanskriti” and “vedik Sanskriti”. Shraman Sanskrit contribution of monuments, how various texts and was developed by “Sindhu Sanskriti” which their translations acted as catalysts; and the believes In hard work, equality and peace. contribution of European Indologists towards Archaeological surveys and excavations produced spreading Buddhism in Western countries. The many pieces of evidence that prove that the original major question the paper tackles is how and why natives of India are Buddhist. Referring to an Buddhism ebbed away from India, and also what article from Gail Omvedt’s book “Buddhism in we can learn from the way it came back. -

Revolt Against Schopenhauer and Wagner? 177

Revolt against Schopenhauer and Wagner? 177 Revolt against Schopenhauer and Wagner? An Insight into Nietzsche’s Perspectivist Aesthetics MARGUS VIHALEM The article focuses on the basic assumptions of Nietzschean aesthetics, arguing that Nietzsche’s aesthetics in his later period cannot be thoroughly understood outside of the context of the long-term conflict with romanticist ideals and without considering Arthur Schopenhauer’s and Richard Wagner’s aesthetic and metaphysical positions. Nietzsche’s thinking on art and aesthetics is in fact inseparable from his philosophical standpoint, which complements and renders explicit the hidden meaning of his considerations on art. The article pays particular attention to Nietzsche’s writings on Wagner and Wagnerism and attempts to show that the ideas expressed in these writings form the very basis of Nietzschean aesthetics and, to some extent, had a remarkable impact on his whole philosophy. The article also argues that Nietzsche’s aesthetics may even be regarded, to a certain extent, as the cornerstone of his philosophical project. Only aesthetically can the world be justified. – Friedrich Nietzsche1 I The background: Christianity, romanticism and Schopenhauer Nietzsche undoubtedly stands as one of the most prominent figures of the anti- romanticist philosophy of art in the late nineteenth century, opposing to the ro- manticist vision of the future founded on feebleness the classic vision of the fu- ture based on forcefulness and simple beauty.2 Nietzsche’s influence can be seen extensively in very different realms of twentieth-century philosophical thinking on art, from philosophical aesthetics to particular art procedures and techniques. The specific approach he endorsed concerning matters of art and aesthetics is by 1 F. -

Songs of the Last Philosopher: Early Nietzsche and the Spirit of Hölderlin

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2013 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2013 Songs of the Last Philosopher: Early Nietzsche and the Spirit of Hölderlin Sylvia Mae Gorelick Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2013 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Recommended Citation Gorelick, Sylvia Mae, "Songs of the Last Philosopher: Early Nietzsche and the Spirit of Hölderlin" (2013). Senior Projects Spring 2013. 318. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2013/318 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Songs of the Last Philosopher: Early Nietzsche and the Spirit of Hölderlin Senior Project submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Sylvia Mae Gorelick Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 1, 2013 For Thomas Bartscherer, who agreed at a late moment to join in the struggle of this infinite project and who assisted me greatly, at times bringing me back to earth when I flew into the meteoric heights of Nietzsche and Hölderlin’s songs and at times allowing me to soar there.