Vedanta in the West: Past, Present, and Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P. Vasundhara Rao.Cdr

ORIGINAL ARTICLE ISSN:-2231-5063 Golden Research Thoughts P. Vasundhara Rao Abstract:- Literature reflects the thinking and beliefs of the concerned folk. Some German writers came in contact with Ancient Indian Literature. They were influenced by the Indian Philosophy, especially, Buddhism. German Philosopher Arther Schopenhauer, was very much influenced by the Philosophy of Buddhism. He made the ancient Indian Literature accessible to the German people. Many other authors and philosophers were influenced by Schopenhauer. The famous German Indologist, Friedrich Max Muller has also done a great work, as far as the contact between India and Germany is concerned. He has translated “Sacred Books of the East”. INDIAN PHILOSOPHY IN GERMAN WRITINGS Some other German authors were also influenced by Indian Philosophy, the traces of which can be found in their writings. Paul Deussen was a great scholar of Sanskrit. He wrote “Allgemeine Geschichte der Philosophie (General History of the Philosophy). Friedrich Nieztsche studied works of Schopenhauer in detail. He is one of the first existentialist Philosophers. Karl Eugen Neuman was the first who translated texts from Pali into German. Hermann Hesse was also influenced by Buddhism. His famous novel Siddhartha is set in India. It is about the spiritual journey of a man (Siddhartha) during the time of Gautam Buddha. Indology is today a subject in 13 Universities in Germany. Keywords: Indian Philosophy, Germany, Indology, translation, Buddhism, Upanishads.specialization. www.aygrt.isrj.org INDIAN PHILOSOPHY IN GERMAN WRITINGS INTRODUCTION Learning a new language opens the doors of a different culture, of the philosophy and thinking of that particular society. How true it is in case of Indian philosophy having traveled to Germany years ago. -

Sri Ramakrishna & His Disciples in Orissa

Preface Pilgrimage places like Varanasi, Prayag, Haridwar and Vrindavan have always got prominent place in any pilgrimage of the devotees and its importance is well known. Many mythological stories are associated to these places. Though Orissa had many temples, historical places and natural scenic beauty spot, but it did not get so much prominence. This may be due to the lack of connectivity. Buddhism and Jainism flourished there followed by Shaivaism and Vainavism. After reading the lives of Sri Chaitanya, Sri Ramakrishna, Holy Mother and direct disciples we come to know the importance and spiritual significance of these places. Holy Mother and many disciples of Sri Ramakrishna had great time in Orissa. Many are blessed here by the vision of Lord Jagannath or the Master. The lives of these great souls had shown us a way to visit these places with spiritual consciousness and devotion. Unless we read the life of Sri Chaitanya we will not understand the life of Sri Ramakrishna properly. Similarly unless we study the chapter in the lives of these great souls in Orissa we will not be able to understand and appreciate the significance of these places. If we go on pilgrimage to Orissa with same spirit and devotion as shown by these great souls, we are sure to be benefited spiritually. This collection will put the light on the Orissa chapter in the lives of these great souls and will inspire the devotees to read more about their lives in details. This will also help the devotees to go to pilgrimage in Orissa and strengthen their devotion. -

Polyclinic News

Volume:-11, No. 5 Dec. 16 to Jan. 17 “They alone live who live for others. The rest are more dead than alive.” Polyclinic News Ramakrishna Mission Sevashrama, Lucknow, runs the Vivekananda Polyclinic & Institute of Medical Sciences, a 350 bedded multi-speciality community hospital with the objective of providing quality healthcare at the lowest cost to all patients and to provide charity services to deserving patients from the lower socio-economic strata. Upgradation of Equipment in Physiotherapy: The Physiotherapy Department of Vivekananda Polyclinic & Institute of Medical Sciences (VPIMS), Lucknow has been continuously upgrading its equipment profile and has procured 02 Multi-channel Microprocessor Based TENS and 02 Hydro collator Machine (8 Packs large size) manufactured by Rapid Electro Med. The machines were inaugurated on 21st December 2017 by Swami Muktinathananda, the Secretary of the Institute. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) are predominately used for nerve related pain conditions (acute and chronic conditions). TENS machines works by sending stimulating pulses across the surface of the skin and along the nerve strands. The stimulating pulses help prevent pain signals from reaching the brain. Tens devices also stimulate the body to produce higher levels of its own natural painkillers, called "Endorphins". It can be used for pain relief in several types of illness and conditions such as Osteoarthritis, acute lumbar and cervical pain, tendinitis and bursitis. Hydro Collator is a stationary or mobile stainless steel thermo statistically controlled water heating device designed to 0 heat silica field packs in water up to 160 C. The packs are removed and wrapped in several layers of towel and applied to the affected part of the body. -

"Das Tier, Das Dujetzttötest, Bist Du Selbst Arthurschopenhauer Und

"Das Tier, das du jetzt tötest, bist du selbst Arthur Schopenhauer 4 und Indien Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung anlässlich der Buchmesse 2006 Zusammengestellt und "Das Thier, das Carica p 80 Tat-twam-asi herausgegeben von Du jetzt tödtest bist Du selbst, bist Wer das Tatgumes es - Jochen Stollberg jetzt." Die Seelenwanderung begreift, hat auch die ist die bildliche Einkleidung des Idealität des Raumes (Tat twam asi) u. der Zeit begriffen Tatoumes d. h. "Dies bist Du", für - u. umgekehrt. diejenigen, denen obiger Kantischer Satz oder sein Aequivalent, das Tat twam asi fasslich zu machen Tatoumes nicht beizubringen war. Arthur Schopenhauer, Foliant 2, Bi. 193r [Manuskriptbuchl Berlin 1826 VITTORIO KLOSTERMANN FRANKFURT AM MAIN Inhalt Klaus Ring Zum Geleit Matthias Koßler Grußwort Jochen Stollberg Arthur Schopenhauers Annäherung an die indische Welt 5 Urs App OUM - das erste Wort von Schopenhauers Lieblingsbuch 37 Urs App NICHTS - das letzte Wort von Schopenhauers Hauptwerk 51 Douglas L. Berger Erbschaften einer philosophischen Begegnung 61 Stephan Atzert Nirvana und Maya bei Schopenhauer 79 Heiner Feldhoff Und dann und wann ein weiser Elefant - Über Paul Deussens "Erinnerungen Indien" 85 Michael Gerhard Paul Deussen - Eine deutsch-indische Geistesbeziehung 101 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Arati Barua verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek of in India - Deutschen detaillierte bibliographische Daten Re-discovery Schopenhauer Nationalbibliographie; of the work and of sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Founding membership Indian branch of Schopenhauer Society 119 Thomas Frankfurter Bibliotheksschriften Regehly Schopenhauer und Siddharta 135 Herausgegeben von der Gesellschaft der Freunde der Stadt- und Universitätsbibliothek Frankfurt am Main e. -

Balancing Inner and Outer

Editorial Balancing Inner and Outer As the Holy Mother Sesquicentennial Year nears its conclusion, this is perhaps a good time to take stock of what we have learned from Holy Mother’s life and teachings. As spiritual aspirants, we gain a great deal of inspiration for our interior life from her teachings on devotion, work, knowledge, self-effort and self-surrender. From her life, we see how a person living in domestic circumstances can be pure and non-attached as well as loving and concerned. She played her part faultlessly, showing how the highest ideals can be made practical in the workaday world. In some ways her workaday world was a very different place from ours. She did not face the stress of the modern workplace or such a dizzying pace of technological change. But Holy Mother’s world did include terrorism, including state terror, political upheaval, and social stress. Great teachers do not always give us specific answers to specific external challenges. Rather, they give us examples and principles that help us to make the right decisions as we respond to our own particular challenges. We have to engage in our own struggle in our own circumstances. One thing is clear: Holy Mother never attempted to escape or run away from difficulties. Think of her life in the cramped, stuffy Nahabat, without toilet facilities, with fish for her husband’s delicate stomach splashing water all night from a pot hung from the ceiling. Think of her difficulties in Kamarpukur after the Master’s passing, with hardly enough to eat or wear and the constant criticism of her neighbors. -

2021 2020 2021

VEDANTA SOCIETY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA CALENDAR OF OBSERVANCES AND OTHER SPECIAL DAYS 2020 – 2021 (PUBLIC CELEBRATIONS IN BOLD) KALI IMMERSION Nov 17 Tue 2020 (In Newport Beach) SHANKARACHARYA Apr 28 Tue JAGADDHATRI PUJA Nov 23 Mon BUDDHA PURNIMA (In Hollywood) May 7 Thu THANKSGIVING Nov 26 Thu PHALAHARINI KALI PUJA May 22 Fri SWAMI SUBODHANANDA Nov 26 Thu MEMORIAL DAY RETREAT May 25 Mon SWAMI VIJNANANANDA Nov 29 Sun (In Hollywood) SNANA YATRA Jun 5 Fri HANUKKAH Dec 10 – 18 Thu - Fri RATHA YATRA Jun 23 Tue SWAMI PREMANANDA Dec 23 Wed VIVEKANANDA DAY CHRISTMAS EVE SERVICE Jul 4 Sat Dec 24 Thu (In Trabuco) (6 PM) GURU PURNIMA Jul 5 Sun JESUS CHRIST (Christmas Day) Dec 25 Fri VIVEKANANDA DAY NEW YEAR'S EVE MEDITATION Jul 11 Sat Dec 31 Thu (In South Pasadena) (11:30 PM - Midnight) SWAMI RAMAKRISHNANANDA Jul 18 Sat 2021 SWAMI NIRANJANANANDA Aug 3 Mon KALPATARU DAY Jan 1 Fri SRI KRISHNA PUJA Aug 9 Sun HOLY MOTHER Celebration Jan 3 Sun (In San Diego) Sri Krishna Janmashtami Aug 11 Tue HOLY MOTHER BIRTHDAY Jan 5 Tue SWAMI ADVAITANANDA Aug 18 Tue SWAMI SHIVANANDA Jan 9 Sat GANESH CHATURTHI Aug 22 Sat SWAMI SARADANANDA Jan 19 Tue LABOR DAY RETREAT Sep 7 Mon SWAMI TURIYANANDA Jan 27 Wed (In Hollywood) SWAMI ABHEDANANDA Sep 11 Fri SWAMI VIVEKANANDA Feb 4 Thu MAHALAYA Sep 17 Thu SWAMI VIVEKANANDA PUJA Feb 7 Sun SWAMI AKHANDANANDA Sep 17 Thu SWAMI BRAHMANANDA Feb 13 Sat NAVARATRI CHANTING Oct 17 – 26 SWAMI BRAHMANANDA PUJA Feb 14 Sun (Jai Sri Durga) Sat - Mon DURGA SAPTAMI Oct 23 Fri SWAMI TRIGUNATITANANDA Jan 15 Mon DURGA ASHTAMI Oct 24 Sat SARASWATI PUJA Feb 16 Tue SANDHI PUJA (6.35 am – 7.23 am) Oct 24 Sat SWAMI ADBHUTANANDA Feb 27 Sat DURGA PUJA (In Santa Barbara) Oct 24 Sat SHIVA RATRI Mar 11 Thu DURGA NAVAMI Oct 25 Sun SRI RAMAKRISHNA Celebration Mar 14 Sun VIJAYA DASHAMI Oct 26 Mon SRI RAMAKRISHNA BIRTHDAY Mar 15 Mon LAKSHMI PUJA Oct 30 Fri SRI CHAITANYA (Holi Festival) Mar 28 Sun KALI PUJA (In Hollywood) Nov 14 Sat SWAMI YOGANANDA Apr 1 Thu . -

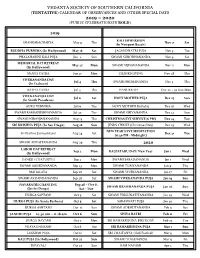

2020 2019 2020

VEDANTA SOCIETY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA (TENTATIVE) CALENDAR OF OBSERVANCES AND OTHER SPECIAL DAYS 2019 – 2020 (PUBLIC CELEBRATIONS IN BOLD) 2019 KALI IMMERSION SHANKARACHARYA May 9 Thu Nov 2 Sat (In Newport Beach) BUDDHA PURNIMA (In Hollywood) May 18 Sat JAGADDHATRI PUJA Nov 5 Tue PHALAHARINI KALI PUJA Jun 2 Sun SWAMI SUBODHANANDA Nov 9 Sat MEMORIAL DAY RETREAT May 27 Mon SWAMI VIJNANANANDA Nov 11 Mon (In Hollywood) SNANA YATRA Jun 17 Mon THANKSGIVING Nov 28 Thu VIVEKANANDA DAY Jul 4 Thu SWAMI PREMANANDA Dec 5 Thu (In Trabuco) RATHA YATRA Jul 4 Thu HANUKKAH Dec 22 – 30 Sun-Mon VIVEKANANDA DAY Jul 6 Sat HOLY MOTHER PUJA Dec 15 Sun (In South Pasadena) GURU PURNIMA Jul 16 Tue HOLY MOTHER Birthday Dec 18 Wed SWAMI RAMAKRISHNANANDA Jul 30 Tue SWAMI SHIVANANDA Dec 22 Sun SWAMI NIRANJANANANDA Aug 15 Thu CHRISTMAS EVE SERVICE(6 PM) Dec 24 Tue SRI KRISHNA PUJA (In San Diego) Aug 18 Sun JESUS CHRIST (Christmas Day) Dec 25 Wed NEW YEAR'S EVE MEDITATION Sri Krishna Janmashtami Aug 24 Sat Dec 31 Tue (11:30 PM - Midnight) SWAMI ADVAITANANDA Aug 29 Thu 2020 LABOR DAY RETREAT Sep 2 Mon KALPATARU DAY/ New Year Jan 1 Wed (In Hollywood) GANESH CHATURTHI Sep 2 Mon SWAMI SARADANANDA Jan 1 Wed SWAMI ABHEDANANDA Sep 23 Mon SWAMI TURIYANANDA Jan 9 Thu MAHALAYA Sep 28 Sat SWAMI VIVEKANANDA Jan 17 Fri SWAMI AKHANDANANDA Sep 28 Sat SWAMI VIVEKANANDA PUJA Jan 19 Sun NAVARATRI CHANTING Sep 28 – Oct 8, SWAMI BRAHMANANDA PUJA Jan 26 Sun (Jai Sri Durga) Sat - Tue DURGA SAPTAMI Oct 5 Sat SWAMI TRIGUNATITANANDA Jan 29 Wed DURGA PUJA (In Santa Barbara) Oct 5 Sat SARASWATI PUJA Jan 30 Thu DURGA ASHTAMI Oct 6 Sun SWAMI ADBHUTANANDA Feb 9 Sun SANDHI PUJA 10.30 am – 11.18 am Oct 6 Sun SHIVA RATRI Feb 21 Fri DURGA NAVAMI Oct 7 Mon SRI RAMAKRISHNA BIRTHDAY Feb 25 Tue VIJAYA DASHAMI Oct 8 Tue SRI RAMAKRISHNA PUJA Mar 1 Sun LAKSHMI PUJA Oct 12 Sat SRI CHAITANYA (Holi Festival) Mar 9 Mon KALI PUJA (In Hollywood) Oct 27 Sun SWAMI YOGANANDA Mar 13 Fri DIPAVALI Oct 27 Sun RAM NAVAMI Apr 2 Thu . -

Vedanta Society of Northern California

VEDANTA SOCIETY OF NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 2323 Vallejo Street (at Fillmore) San Francisco, CA 94123 Swami Tattwamayananda, Minister and Spiritual Teacher Swami Asutoshananda, Assistant Minister Ramakrishna Order of India APRIL 2016 Friday, April 1, 7:30 p.m. — Scripture Class: “Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras” Vivekananda Hall Swami Tattwamayananda SUNDAY, April 3, 11 a.m. — “CLIMATE CHANGE: A VEDANTIC PERSPECTIVE” Swami Tattwamayananda Wednesday, April 6, 7:30 p.m. — Vespers and Meditation Friday, April 8, 7:30 p.m. — NO SCRIPTURE CLASS SUNDAY, April 10, 11 a.m. — “WHAT SHOULD WE ACCOMPLISH HERE?” Swami Vedananda Wednesday, April 13, 7:30 p.m. — Vespers and Meditation Friday, April 15, 7:30 p.m. — Scripture Class: “Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras” Vivekananda Hall Swami Tattwamayananda SUNDAY, April 17, 11 a.m. — “A SPIRITUAL IDEAL FOR AMERICA” Swami Tattwamayananda Wednesday, April 20, 7:30 p.m. — Vespers and Meditation Friday, April 22, 7:30 p.m. — Scripture Class: “Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras” Vivekananda Hall Swami Tattwamayananda SUNDAY, April 24, 11 a.m. — “THE TRANSFORMING POWER OF HOLY COMPANY” Pravrajika Virajaprana Wednesday, April 27, 7:30 p.m. — Vespers and Meditation Friday, April 29, 7:30 p.m. — NO SCRIPTURE CLASS Saturday, April 30, 11 a.m. — SHANTI ASHRAMA PILGRIMAGE Phone: 415-922-2323 Fax: 415-922-1476 Website: www.sfvedanta.org E-mail: [email protected] Swami Tattwamayananda’s E-mail: [email protected] inspire reverence for the great religious teachers of the world. Parents wishing to enroll their children are invited to speak to the secretary of the Society. THE SRI SARADA LIBRARY is open on Sundays, following the lecture, from 12:30 to 2:30 p.m., and at other times by appointment. -

Attitude of Vedanta Towards Religion

OSMANIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY q Author,' A b h e d n r: a n fl a . \v PPI 1 Title Attitude of veflnnta tovarfln This hook should be returned on or before the dale l;w marked below, SWAM1 ABHEDANANBA, aa apostle of Sri Ramakrishna Born October 2, 1866 Spent his early life among his brotherhood in Baranagar monastery near Calcutta, in severe austerity Travelled bare-footed all over India from 1888-1895 Acquainted with many distinguished savants including Prof. Max Mueller and Prof. Paul Deussen Landed inj&ew * 'tbtft the* charge of the Vedanta Society in 1897 Became with Prof. Rev. acquainted William ]ames / Dr. R. H. Newton, Prof. W. Jackson, Prof. Josiah Royce of Harvard/ Prof. Hyslop of Columbia, Prof. Lanmann, Prof. G. H. Howison, Prof. Fay, Mr. Edison, the inventor, Dr. Elmer Gates, Ralph Waldo Trine, W. D. Howells, Prof. Herschel C. Parker, Dr. H..S. Logan, Rev. Bishop Potter, Prof. Shaler Dr. James, the chairman of the Cambridge Philosophical Conference and the professors of Columbia, Harvard, Yale, Cornell, Berkeley and Clarke Universities Travelled extensively all through the United States, Canada, Alaska and Mexico Made frequent trips to Europe delivering lectures in different parts of the Continent Crossed the Atlantic for seventeen times Was appreciated very much for his profundity of intellectual scholarship, brilliance / oratorial talents, charming personality and nobility of character A short visit to India in 1906 Returned again to America Came back to India at last in 1921 On his way home joined the Educational Conference, Honolulu Visited Japan, China/ the Philipines, Singapore, Kualalumpur and Rangoon -Started on a long tour and went as far as Tibet -Established centres at Calcutta and Darjeeling Left his mortal frame on September 8, 1939. -

The Gospel of the Holy Mother Sri Sarada Devi Recorded by HER DEVOTEE – CHILDREN

The Gospel of the Holy Mother Sri Sarada Devi Recorded by HER DEVOTEE – CHILDREN Page 1 of 769 PREFACE 'The Gospel of the Holy Mother Sri Sarada Devi', is the full translation of the Bengali work 'Sri Sri Mayer Katha', parts of which have already come out in translation under other titles. This Math itself had published some important sections of it as early as 1940 under the title 'Conversations of the Holy Mother', incorporated in her biography 'Sri Sarada Devi the Holy Mother'. The present book, however, embodies the whole of the Bengali text. Most of the reminiscences and conversations of the Holy Mother, except what appears in the great work of Swami Saradeshananda, entitled 'The Mother as I saw her', also published by this Math, are now available for the English reading public in one volume. Recorded as it is by a large number of the devotee- children of the Mother, the present book reveals to mankind a great character that chose to remain outside public notice behind the Purdah and in the obscurity of the village of Jayrambati. Even under these conditions the great lady's greatness could not be obscured. Through the impressions and recollections of a large number of men and women of various stations in life, who came into contact with Sri Sarada Devi, her greatness emerges in Page 2 of 769 the bright colours of Universal Motherhood, never before witnessed in so striking a manner in any personality we know of. Therefore, while the contents of this book are of special importance to the followers of Sri Ramakrishna, they can make an appeal to all who appreciate the great human value of motherliness. -

The Philosophy of the Vedanta in Its Relations to the Occidental Metaphysics by Dr

Adyar Pamphlets The Philosophy of the Vedanta in Its Relations... No. 136 The Philosophy of the Vedanta in Its Relations to the Occidental Metaphysics by Dr. Paul Deussen, Professor of Philosophy in the University of Kiel, Germany An address, delivered before the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Saturday the 25th February, 1893 Published in 1930 Theosophical Publishing House, Adyar, Chennai [Madras] India The Theosophist Office, Adyar, Madras. India [Page 1] ON my journey through India I have noticed with satisfaction, that in philosophy till now our brothers in the East have maintained a very good tradition, better perhaps, than the more active but less contemplative branches of the great Indo-Aryan family in Europe, where Empirism, Realism and their natural consequence, Materialism, grow from day to day more exuberantly, whilst metaphysics, the very center and heart of serious philosophy, are supported only by a few ones, who have learned to brave the spirit of the age. In India the influence of this perverted and pervasive spirit of our age has not yet overthrown in religion and philosophy the good traditions of the great ancient time. It is true, that most of the ancient darsanas even in India find only an historical interest; followers of the Sãnkhya-System occur rarely; Nyãya is cultivated mostly as an intellectual sport and exercise, like grammar or mathematics, but the Vedãntic is, now as in the ancient time living in the mind and heart of every thoughtful Hindu. It is true, that even here in the [Page 2] sanctuary of Vedãntic metaphysics, the realistic tendencies, natural to man, have penetrated, producing the misinterpreting variations of Shankara's Adwaita, known under the names Visishtãdwaita, Dwaita, Cuddhãdwaita of Rãmanuja, Mãdhva, Vallabha, but India till now has not yet been seduced by their voices, and of hundred Vedãntins (I have it from a well informed man, who is himself a zealous adversary of Shankara and follower of Rãmãnuja) fifteen perhaps adhere to Rãmãnuja, five to Madhva, five to Vallabha, and seventy-five to Shankarãchãrya. -

What Is This Center July 5 '20 Talk

Vedanta Center of Atlanta July 5, 2020 What is This Center and Why are We Here? Br. Shankara GOOD MORNING… ANNOUNCEMENTS • Center closed in July July is a month for study of Jnana Yoga (Advaita Vedanta). As a jnana yogi, you practice discrimination, reason, detachment, and satyagraha (insistence on Truth). The goal is freedom from limitation (moksha). Our teachers say that all miseries in life are caused by seeing inaccurately. An earnest and persistent jnani may break through this misapprehension (maya) and see only the Divine Presence everywhere, in everything and everyone. CHANT • SONG • WELCOME • TOPIC What is This Center and Why are We Here? This morning that question will be answered in some detail. We’ll start in 1881, when a teenager named Narendranath Dutta met Sri Ramakrishna. According to Narendra, Ramakrishna carefully trained him for the mission he was to undertake. That training took six years — from 1881, when Narendra was 18 years old, until 1886, when the Master passed away. Narendra was 23. Over the next seven years, from 1886 to 1893, Narendra became Swami Vivekananda, fit for the work Ramakrishna had in mind. The Swami left for America at age 30. He took ship from Mumbai on May 31st, 1893 and docked in Vancouver, British Columbia on July 25th. Then, on September 11th, at the first World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago, Swami Vivekananda spoke the words that began to unfold his destiny as a teacher of Vedanta in the West: “Sisters and brothers of America,” he said, and an audience of thousands rose to offer him a two-minute standing ovation.