Body, Illness and Medicine in Kolkata (Calcutta)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vedanta in the West: Past, Present, and Future

Vedanta in the West: Past, Present, and Future Swami Chetanananda What Is Vedanta? Vedanta is the culmination of all knowledge, the sacred wisdom of the Indian sages, the sum of the transcendental experiences of the seers of Truth. It is the essence, or the conclusion, of the scriptures known as the Vedas. Because the Upanishads come at the end of the Vedas they are collectively referred to as Vedanta. Literally, Veda means "knowledge" and anta means "end." Vedanta is a vast subject. Its scriptures have been evolving for the last five thousand years. The three basic scriptures of Vedanta are the Upanishads (the revealed truths), the Brahma Sutras (the reasoned truths), and the Bhagavad Gita (the practical truths). Some Teachings from Vedanta Here are some teachings from the Upanishads: “Arise! Awake! Approach the great teachers and learn.” “Aham Brahmasmi.” [I am Brahman.] “Tawamasi.” [Thou art That.] “Sarvam khalu idam Brahma.” [Verily, everything is Brahman.] “Whatever exists in this changing universe is enveloped by God.” “If a man knows Atman here, he then aains the true goal of life.” “Om is the bow; the Atman is the arrow; Brahman is said to be the mark. It is to be struck by an undistracted mind.” “He who knows Brahman becomes Brahman.” “His hands and feet are everywhere. His eyes, heads, and mouths are everywhere. His ears are everywhere. He pervades everything in the universe.” “Speak the truth. Practise dharma. Do not neglect your study of the Vedas. Treat your mother as God. Treat your father as God. Treat your teacher as God. -

The Politics of (In)Visibility

The Lesbian Lives Conference 2019: The Politics of (In)Visibility THE POITICS Centre for Transforming Sexuality and Gender & The School of Media University of Brighton 15th - 16th March 2019 Welcome! The organising team would like to welcome you to the 2019 Lesbian Lives conference on the Politics of (In)Visibility. The theme of this year’s conference feels very urgent as attacks on feminism and feminists from both misogynist, homophobic, transphobic and racist quarters are on the rise both here in the UK and elsewhere. It has been thrilling to see the many creative and critical proposals responding to this coming in from academics, students, activists, film-makers, writers artists, and others working in diverse sectors from across many different countries – and now you are here! We are delighted to be hosting the conference in collaboration with feminist scholars from University College Dublin, St Catharine’s College, Cambridge and Maynooth University. It is - what we think - the 24th Lesbian lives conference, although we are getting to the stage where we might start losing count. Let’s just say it is now a conference of some maturity that remains relevant in every age, as the world’s most longstanding academic conference in Lesbian Studies. What we do know is that the first ever Lesbian Lives Conference was held in 1993 in University College Dublin and has been trooping on since, with the dedication of academics and activists and the amazing support from the community. From this comes the unique atmosphere of the Lesbian Lives Conference which is something special – as Katherine O’Donnell, one of the founders of the conference, said: ‘there is a friendliness, a warmth, an excitement, an openness, a bravery and gentleness that every Lesbian Lives Conference has generated’. -

P. Vasundhara Rao.Cdr

ORIGINAL ARTICLE ISSN:-2231-5063 Golden Research Thoughts P. Vasundhara Rao Abstract:- Literature reflects the thinking and beliefs of the concerned folk. Some German writers came in contact with Ancient Indian Literature. They were influenced by the Indian Philosophy, especially, Buddhism. German Philosopher Arther Schopenhauer, was very much influenced by the Philosophy of Buddhism. He made the ancient Indian Literature accessible to the German people. Many other authors and philosophers were influenced by Schopenhauer. The famous German Indologist, Friedrich Max Muller has also done a great work, as far as the contact between India and Germany is concerned. He has translated “Sacred Books of the East”. INDIAN PHILOSOPHY IN GERMAN WRITINGS Some other German authors were also influenced by Indian Philosophy, the traces of which can be found in their writings. Paul Deussen was a great scholar of Sanskrit. He wrote “Allgemeine Geschichte der Philosophie (General History of the Philosophy). Friedrich Nieztsche studied works of Schopenhauer in detail. He is one of the first existentialist Philosophers. Karl Eugen Neuman was the first who translated texts from Pali into German. Hermann Hesse was also influenced by Buddhism. His famous novel Siddhartha is set in India. It is about the spiritual journey of a man (Siddhartha) during the time of Gautam Buddha. Indology is today a subject in 13 Universities in Germany. Keywords: Indian Philosophy, Germany, Indology, translation, Buddhism, Upanishads.specialization. www.aygrt.isrj.org INDIAN PHILOSOPHY IN GERMAN WRITINGS INTRODUCTION Learning a new language opens the doors of a different culture, of the philosophy and thinking of that particular society. How true it is in case of Indian philosophy having traveled to Germany years ago. -

Visualisation of Women in Media, Literature and Science -Dr

1 BARTERED BODIES VISUALISATION OF WOMEN IN MEDIA, LITERATURE AND SCIENCE -DR. KAMAYANI KUMAR Women’s bodies have since time immemorial served as a ‘site’ on which (metaphorically) war is fought and albeit conquest is sought. In this paper I seek to discuss the visualization of women in war literature. I will be looking at Rajwinder Singh Bedi’s story, Lajwanti and Guy de Maupassant’s Boile De Saufe. Prof. Rachel Bari Although Bedi’s short story does not respond to the generic classification of war literature yet it deals with a shared fate of women across borders and boundaries of time/ space that is stigmatization of Rape. Ironically, in war crimes which are an emanation of conflict pertaining to boundaries, rape emerges as the inevitable PRASARANGA insult thrust upon women irrespective of temporal, spatial, ethnic, nationalistic demarcations hence conforming that borders are mere “shadow lines” and that borders which serve to demarcate nations also serve to embroil and entwine nations. Violence done KUVEMPU UNIVERSITY against women’s bodies is as old as human civilizations, as Brownmiller states, “Violence, specifically rape against women, has been part of every documented war in history from the battles of Babylonia to the subjugation of Jewish women in World 2 War II”1 In fact, Biblical references depict women as “spoils of that inscribe the victories, defeats, and heroic battles that war” and there are various accounts of the rape of Sabine women primarily reflect men’s experiences of war. in Roman mythology. “The act of rape as a mechanism for “rewarding the troops” with “booty” has been a common feature Temporally/ spatially/ culturally the trajectory of this paper ranges from literary responses to the Franco Prussian war, in the representation of war.”2 Because soldiers of antiquity were frequently not paid regular wages, sanctioning the raping and Partition of Indian subcontinent in 1947against the theoretical pillaging of the enemy served as a way to motivate them to fight. -

Women at Crossroads: Multi- Disciplinary Perspectives’

ISSN 2395-4396 (Online) National Seminar on ‘Women at Crossroads: Multi- disciplinary Perspectives’ Publication Partner: IJARIIE ORGANISE BY: DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PSGR KRISHNAMMAL COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, PEELAMEDU, COIMBATORE Volume-2, Issue-6, 2017 Vol-2 Issue-6 2017 IJARIIE-ISSN (O)-2395-4396 A Comparative Study of the Role of Women in New Generation Malayalam Films and Serials Jibin Francis Research Scholar Department of English PSG College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore Abstract This 21st century is called the era of technology, which witnesses revolutionary developments in every aspect of life. The life style of the 21st century people is very different; their attitude and culture have changed .This change of viewpoint is visible in every field of life including Film and television. Nowadays there are several realty shows capturing the attention of the people. The electronic media influence the mind of people. Different television programs target different categories of people .For example the cartoon programs target kids; the realty shows target youth. The points of view of the directors and audience are changing in the modern era. In earlier time, women had only a decorative role in the films. Their representation was merely for satisfying the needs of men. The roles of women were always under the norms and rules of the patriarchal society. They were most often presented on the screen as sexual objects .Here women were abused twice, first by the male character in the film and second, by the spectators. But now the scenario is different. The viewpoint of the directors as well as the audience has drastically changed .In this era the directors are courageous enough to make films with women as central characters. -

Bangladeshi Cuisine Is Rich and Varied with the Use of Many Spices

Read the passage carefully and answer the questions following it (1-3). Bangladeshi cuisine is rich and varied with the use of many spices. We have delicious and appetizing food, snacks, and sweets. Boiled rice is our staple food. It is served with a variety of vegetables, curry, lentil soups, fish and meat. Fish is the main source of protein. Fishes are now cultivated in ponds. Also we have fresh-water fishes in the lakes and rivers. More than 40 types of fishes are common, Some of them are carp, rui, katla, magur (catfish), chingri (prawn or shrimp), Shutki or dried fishes are popular. Hilsha is very popular among the people of Bangladesh. Panta hilsha is a traditional platter of Panta bhat. It is steamed rice soaked in water and served with fried hilsha slice, often together with dried fish, pickles, lentil soup, green chilies and onion. It is a popular dish on the Pohela Boishakh. The people of Bangladesh are very fond of sweets. Almost all Bangladeshi women prepare some traditional sweets. ‘Pitha’ a type of sweets made from rice, flour, sugar syrup, molasses and sometimes milk, is a traditional food loved by the entire population. During winter Pitha Utsab, meaning pitha festival is organized by different groups of people, Sweets are distributed among close relatives when there is good news like births, weddings, promotions etc. Sweets of Bangladesh are mostly milk based. The common ones are roshgulla, sandesh, rasamalai, gulap jamun, kaljamun and chom-chom. There are hundreds of different varieties of sweet preparations. Sweets are therefore an important part of the day-to-day life of Bangladeshi people. -

Agricultural Technolongy in Bangladesh: a Study on Non-Farm Labor and Adoption by Gender

AGRICULTURAL TECHNOLONGY IN BANGLADESH: A STUDY ON NON-FARM LABOR AND ADOPTION BY GENDER Melanie V. Victoria Thesis Submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science In Agricultural and Applied Economics George W. Norton, Chair Christopher F. Parmeter Daniel B. Taylor July 16, 2007 Blacksburg, Virginia Tech Keywords: High-yielding varieties, Integrated Pest Management, Bangladesh, Gender, Non-Farm Labor Copyright©2007, Melanie V. Victoria Agricultural Technology in Bangladesh: A Study on Non-Farm Labor and Adoption by Gender Melanie V. Victoria (ABSTRACT) There is growing interest in learning the impacts of agricultural technologies especially in developing economies. Economic analysis may entail assessment of employment and time allocation effects of new technologies. An issue of importance in South Asia is the impacts of technological change on a specific type of occupation: rural non-farm activities. In order to fully understand these effects, the research must integrate gender differences and determine if the results would be similar irrespective of gender. This paper particularly looks at the effects of HYV adoption on time allocation and labor force participation of men and women in non-farm activities. In estimating the effects of HYV adoption on non-farm labor supply, information on the dependent variable, supply of non-farm labor (or the number of days worked while engaged in non-farm labor), is not available for individuals who do not participate in non-farm labor. Hence sample selection or self-selection of individuals occurs. A feasible approach to the problem of sample selection is the use of Heckman’s Two Stage Selection Correction Model. -

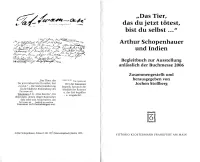

"Das Tier, Das Dujetzttötest, Bist Du Selbst Arthurschopenhauer Und

"Das Tier, das du jetzt tötest, bist du selbst Arthur Schopenhauer 4 und Indien Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung anlässlich der Buchmesse 2006 Zusammengestellt und "Das Thier, das Carica p 80 Tat-twam-asi herausgegeben von Du jetzt tödtest bist Du selbst, bist Wer das Tatgumes es - Jochen Stollberg jetzt." Die Seelenwanderung begreift, hat auch die ist die bildliche Einkleidung des Idealität des Raumes (Tat twam asi) u. der Zeit begriffen Tatoumes d. h. "Dies bist Du", für - u. umgekehrt. diejenigen, denen obiger Kantischer Satz oder sein Aequivalent, das Tat twam asi fasslich zu machen Tatoumes nicht beizubringen war. Arthur Schopenhauer, Foliant 2, Bi. 193r [Manuskriptbuchl Berlin 1826 VITTORIO KLOSTERMANN FRANKFURT AM MAIN Inhalt Klaus Ring Zum Geleit Matthias Koßler Grußwort Jochen Stollberg Arthur Schopenhauers Annäherung an die indische Welt 5 Urs App OUM - das erste Wort von Schopenhauers Lieblingsbuch 37 Urs App NICHTS - das letzte Wort von Schopenhauers Hauptwerk 51 Douglas L. Berger Erbschaften einer philosophischen Begegnung 61 Stephan Atzert Nirvana und Maya bei Schopenhauer 79 Heiner Feldhoff Und dann und wann ein weiser Elefant - Über Paul Deussens "Erinnerungen Indien" 85 Michael Gerhard Paul Deussen - Eine deutsch-indische Geistesbeziehung 101 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Arati Barua verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek of in India - Deutschen detaillierte bibliographische Daten Re-discovery Schopenhauer Nationalbibliographie; of the work and of sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Founding membership Indian branch of Schopenhauer Society 119 Thomas Frankfurter Bibliotheksschriften Regehly Schopenhauer und Siddharta 135 Herausgegeben von der Gesellschaft der Freunde der Stadt- und Universitätsbibliothek Frankfurt am Main e. -

Personal and Domestic Hygiene in Rural Bangladesh

~1O3.0 84PE PERSONAL AND DOMESTIC HYGIENE IN RURAL BANGLADESH LIBRA~ INTERNATIONAL REFERENCE C~NT~ FOR COMMUNITY WATER 8UPPt~ NU cANITATI~1N(IRC~ JITKA KOTALOVA’ 203. 0—84PE—11~79 S (~io~-~Pr C~CCj PERSONAL AND DOJESTIC HYCJIJr EN RURAL BANGLADESH Jitka Kotalcj~~ April 1984 I LIBRARY, INTERNATIONAL REFEWENCE I ~‘fF~ FOR COMMUNtiY WAIEN SUP?LY ~‘\~I \2LXNIIAfl(JN ~IWeI ~ Z7U~4 ‘kb ;ne HRQLS p ~i /3 Mi 49 H ext 1411142 gi~J i1&R-7 2°3~O~ IDA LIST OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Methodology 1 2 GENERAL BACKGROUND 2 3 DRINKING WATER 3 3.1 Water sources 3 Tubewell 3 The Canal 4 The Pond 4 Rain water 5 3.2 Handling and Storage 5 Containers 5 Pumping 5 Boiling 6 Filtering 6 Chemical Purification 6 3.3 Discussion 6 4 DOMESTIC CLEANLINESS 10 4.1 Housing standards 10 4.2 Sleeping and bedding 11 4.3 Vermin 11 4.4 Disposal of wastes 12 Garbage 12 Latrines 12 Urinal 12 5 COOKING AND EATING MANNERS 14 5.1 Preparation of food 14 5.2 Serving of meals and eating 14 5.3 Cleaning up 15 5.4 Feeding children 15 5.5 Preservation of leftovers 16 6 PERSONAL CLEANLINESS 18 6.1 Concept of pollution and purity 18 6.2 Purifying and cosmetic agents 19 Origin 19 Water and Oil 20 Soap 20 Mud 24 6.3 Bathing 24 Technique, frequency and symbolic meaning 24 Daily procedure 25 Cosmetiziation 26 Body—washing procedures 26 6.4 Toilet habits and toilet training 28 6.5 Nasal and oral hygiene 29 6.6 Cleaning of eyes and ears 31 6.7 Hair, nails and general grooming 31 Notes 35 References 38 H/84—6/841 031 .~ S I D A ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research on which this paper is based was supported by funds from the Swedish Development Cooperation Office in Dhaka and the Swedish Council for Research in the Humanities and Social Sciences. -

SET 1 Sample Question for JSC Examination Full Marks

SET 1 Sample question for JSC examination Full marks: 100 Time: 3 hours Marks for individual items are mentioned next to the test items. A: Seen part Read the text and answer questions 1 and 2. Bangladeshi cuisine is rich and varied with the use of many spices. We have delicious and appetizing food, snacks and sweets. Boiled rice is our staple food. It is served with a variety of vegetables, curry, lentil soup, fish and meat. Fish is our main source of protein. Fishes are now cultivated in ponds. Also we have fresh-water fishes in the lakes and rivers. More than 40 types of fishes are common. Some of them are carp, rui, katla, magur (catfish), chingri (prawn or shrimp). Shutki or dried fishes are popular. Hilsha is very popular among the people of Bangladesh. Panta-ilish is a traditional platter of Panta bhat. It is steamed rice soaked in water and served with a fried hilsha slice, often together with dried fish, pickles, lentil soup, green chilies and onion. It is a popular dish on the Pohela Boishakh. The people of Bangladesh are very fond of sweets. Almost all Bangladeshi women prepare some traditional sweets. Pitha, a type of sweets made from rice flour, sugar, syrup, molasses and sometimes milk, is a traditional food loved by the entire population. During winter Pitha Utsab, meaning pitha festival, is organized by different groups of people. Sweets are distributed among close relatives when there is good news like births, weddings, promotions, etc. Sweets of Bangladesh are mostly milk-based. The common ones are roshgolla, sandesh, rasamalai, gulap jamun and cham-cham. -

Réal Ménard : « Gai, Nationaliste Et Fier »1 Un Député Engagé Aux Côtés

MÉMOIRE DE NOTRE COMMUNAUTL’ É Archigai BULLETIN DES ARCHIVES GAIES DU QUÉBEC _ N0 23 _ OCTOBRE 2013 Réal Ménard : « Gai, nationaliste et fier 1» Un député engagé aux côtés de la communauté Photo de Réal Ménard dans son bureau, à Ottawa, prise par Normand Blouin de l’Agence Stock et publiée dans l’article de Lyle Stewart, « “Gay, nationalist and proud” : Réal Ménard is Canada’s newest out MP », Mirror, 13-20 octobre 1994, p.10. armi les nombreux fonds entrés ces dix dernières années aux attaché politique auprès de la députée Louise Harel pendant cinq ans3. Archives gaies du Québec (AGQ), celui de Réal Ménard, homme Élu député fédéral de la circonscription d’Hochelaga le 25 octobre Ppolitique et député fédéral, fait partie de ces témoignages de 1993, il démissionne en 2009 pour rejoindre la politique municipale de luttes engagées pour la reconnaissance des droits des homosexuels au Montréal. Canada. Bien qu’il ne couvre que les seize années d’activité politique de Réal Ménard lorsqu’il siégeait comme député du Bloc Québécois à Au cours de ses seize années de députation pour le Bloc Québécois la Chambre des Communes, soit de 1993 à 2009, il constitue un maillon dans Hochelaga, il occupe successivement les postes de porte-parole, essentiel de notre histoire communautaire. Les dossiers réunis dans les notamment pour la Stratégie nationale sur le Sida (1993 à 2009), et quatre boites qui le composent se partagent en effet entre deux sujets de vice-président, pour, entre autres, le Comité permanent de la santé ayant profondément marqué la dernière décennie de l’actualité gaie du (2002-2004) et le Comité permanent de la justice et des droits de la XXe siècle : les revendications liées à la reconnaissance des conjoints personne (2006-2009). -

Federal Court Final Settlement Agreement 1

1 Court File No.: T-370-17 FEDERAL COURT Proposed Class Proceeding TODD EDWARD ROSS, MARTINE ROY and ALIDA SATALIC Plaintiffs - and - HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN Defendant FINAL SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT WHEREAS: A. Canada took action against members of the Canadian Armed Forces (the "CAF"), members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (the "RCMP") and employees of the Federal Public Service (the “FPS”) as defined in this Final Settlement Agreement (“FSA”), pursuant to various written policies commencing in or around 1956 in the military and in or around 1955 in the public service, which actions included identifying, investigating, sanctioning, and in some cases, discharging lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender members of the CAF or the RCMP from the military or police service, or terminating the employment of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender employees of the FPS, on the grounds that they were unsuitable for service or employment because of their sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression (the “LGBT Purge”); B. In 2016, class proceedings were commenced against Canada in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice, the Quebec Superior Court and the Federal Court of Canada in connection with the LGBT Purge, and those proceedings have been stayed on consent or held in abeyance while this consolidated proposed class action (the “Omnibus Class Action”) has been pursued on behalf of all three of the representative plaintiffs in the preceding actions; C. The plaintiffs, Todd Edward Ross, Martine Roy and Alida Satalic (the “Plaintiffs”) commenced the Omnibus Class Action in the Federal Court (Court File No. T-370-17) on March 13, 2017 by the Statement of Claim attached as Schedule “A”.