The Fugitive Slave Issue in South Central Pennsylvania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Underground Railroad Free Press, January 2012

® Underground Railroad Free Press Independent reporting on today’s Underground Railroad January, 2012 urrfreepress.com Volume 7, Issue 34 McGill Slave Cabin Overnight Stays Propel Restoration As one travels through the countryside of the difference vividly are the stark dissimilarities urrFreePress.com South, the dwindling number of plantations between a plantation's "big house" and its remaining from a time gone by now more slave cabins if the latter still exist at all. strongly beckon tourists, writers, archeolo- gists and the curious for the hidden stories Editorial they tell. Generations of African-Americans International Underground found these places unpleasant and seldom Railroad a Modern Necessity visited but now that is changing with a rising The Underground Railroad and age group far enough removed from slavery, Civil War ended most but not all Jim Crow and segregation to be increasingly slavery in the United States. An inquisitive about the actual locales where estimated 27 million people live American slavery was concentrated. in slavery today, 40,000 of them As old plantations become more open to the in the United States, mainly in public, visitors see first hand the contrast be- agriculture , sweatshops and pro- tween enslaver and enslaved. Portraying the Please see McGill, page 3, column 1 stitution. This modern horror has prison New Underground Railroad Museum Draws Thousands slaves in China producing goods By Peter Slocum, North Country Underground which feature stories of runaways who es- at zero labor cost for world mar- Railroad Historical Association caped to Canada on the Champlain Line of kets, Saharan children "bonded" the Underground Railroad. -

African American Literature in Transition, 1850–1865

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42748-7 — African American Literature in Transition Edited by Teresa Zackodnik Frontmatter More Information AFRICAN AMERICAN LITERATURE IN TRANSITION, – The period of – consists of violent struggle and crisis as the United States underwent the prodigious transition from slaveholding to ostensibly “free” nation. This volume reframes mid-century African American literature and challenges our current understand- ings of both African American and American literature. It presents a fluid tradition that includes history, science, politics, economics, space and movement, the visual, and the sonic. Black writing was highly conscious of transnational and international politics, textual circulation, and revolutionary imaginaries. Chapters explore how Black literature was being produced and circulated; how and why it marked its relation to other literary and expressive traditions; what geopolitical imaginaries it facilitated through representation; and what technologies, including print, enabled African Americans to pursue such a complex and ongoing aesthetic and political project. is a Professor in the English and Film Studies Department at the University of Alberta, where she teaches critical race theory, African American literature and theory, and historical Black feminisms. Her books include The Mulatta and the Politics of Race (); Press, Platform, Pulpit: Black Feminisms in the Era of Reform (); the six-volume edition African American Feminisms – in the Routledge History of Feminisms series (); and “We Must be Up and Doing”: A Reader in Early African American Feminisms (). She is a member of the UK-based international research network Black Female Intellectuals in the Historical and Contemporary Context, and is completing a book on early Black feminist use of media and its forms. -

Frederick Douglass

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection AMERICAN CRISIS BIOGRAPHIES Edited by Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, Ph. D. Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Zbe Hmcrican Crisis Biographies Edited by Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, Ph.D. With the counsel and advice of Professor John B. McMaster, of the University of Pennsylvania. Each I2mo, cloth, with frontispiece portrait. Price $1.25 net; by mail» $i-37- These biographies will constitute a complete and comprehensive history of the great American sectional struggle in the form of readable and authoritative biography. The editor has enlisted the co-operation of many competent writers, as will be noted from the list given below. An interesting feature of the undertaking is that the series is to be im- partial, Southern writers having been assigned to Southern subjects and Northern writers to Northern subjects, but all will belong to the younger generation of writers, thus assuring freedom from any suspicion of war- time prejudice. The Civil War will not be treated as a rebellion, but as the great event in the history of our nation, which, after forty years, it is now clearly recognized to have been. Now ready: Abraham Lincoln. By ELLIS PAXSON OBERHOLTZER. Thomas H. Benton. By JOSEPH M. ROGERS. David G. Farragut. By JOHN R. SPEARS. William T. Sherman. By EDWARD ROBINS. Frederick Douglass. By BOOKER T. WASHINGTON. Judah P. Benjamin. By FIERCE BUTLER. In preparation: John C. Calhoun. By GAILLARD HUNT. Daniel Webster. By PROF. C. H. VAN TYNE. Alexander H. Stephens. BY LOUIS PENDLETON. John Quincy Adams. -

The Underground Railroad in Tennessee to 1865

The State of State History in Tennessee in 2008 The Underground Railroad in Tennesseee to 1865 A Report By State Historian Walter T. Durham The State of State History in Tennessee in 2008 The Underground Railroad in Tennessee to 1865 A Report by State Historian Walter T. Durham Tennessee State Library and Archives Department of State Nashville, Tennessee 37243 Jeanne D. Sugg State Librarian and Archivist Department of State, Authorization No. 305294, 2000 copies November 2008. This public document was promulgated at a cost of $1.77 per copy. Preface and Acknowledgments In 2004 and again in 2006, I published studies called The State of State History in Tennessee. The works surveyed the organizations and activities that preserve and interpret Tennessee history and bring it to a diverse public. This year I deviate by making a study of the Under- ground Railroad in Tennessee and bringing it into the State of State History series. No prior statewide study of this re- markable phenomenon has been produced, a situation now remedied. During the early nineteenth century, the number of slaves escaping the South to fi nd freedom in the northern states slowly increased. The escape methodologies and ex- perience, repeated over and over again, became known as the Underground Railroad. In the period immediately after the Civil War a plethora of books and articles appeared dealing with the Underground Railroad. Largely written by or for white men, the accounts contained recollections of the roles they played in assisting slaves make their escapes. There was understandable exag- geration because most of them had been prewar abolitionists who wanted it known that they had contributed much to the successful fl ights of a number of slaves, oft times at great danger to themselves. -

Lire MALADMINISTRATION of LIBBY and ANDERSONVILLE PRISON CAMPS

'lIRE MALADMINISTRATION OF LIBBY AND ANDERSONVILLE PRISON CAMPS A Study of Mismanagement and Inept Log1st1cal ~olic1es at Two Southern Pr1soner-of-war Camps during the C1v1l war In Accordance w1th the Requirements and Procedures of Interdepartmental 499.0 Under the Direction and Gu1dance of Doctor Will1am Eidson. Associate Professor of H1story. Ball State University Presented as a Senior Honors 'rhes1s by Dan1el Patrick Brown w1nter Quarter, 1971-72 Ball State Univers1ty i 7/::; I rec.ommend this thesis for acceptance by the Ball state Univers1ty Honors Program. Further, I endorse this thesis as valid reference material to be utilized in the Ball state University Library. ,i William G. Eidson, Department of History Thesis Advisor (Date) 'rHE MALADMINISTRATION OF LIBBY AND ANDERSONVILLE PRISON CAMPS INTRODUCTION Pr1soner-of-war suffer1ng has been perhaps the most un fortunate ram1ficat10n of war itself. It 1s th1s paper's purpose to analyze the orig1nal cause of pr1soner-of-war suffer1ng in the Confederate states of Amer1ca during the Amer1can C1v1l war. Certa1nly, the problem of leg1t1mate treatment of prisoners··of-war st1ll plagues mank1nd. The respons1bli ty of po11 tic:al states in the1r treatment of these pr1soners, the naturEI and character of the Confederate leaders accused of pr1sonElr cruelty, misappropr1at10n. and m1smanagement. and the adverse conditions naturally inherent with war; all, over a century after they became 'faits accomplis,' loom 1n the minds of po11t1cal and mi11tary leaders of today's world. In countlE~ss examples, from the newly estab11shed countr1es of Africa and As1a to the world's oldest democratic republic,* war crime::;' tr1als clearly demonstrate man' s continued search for the reasons of maltreatment to the victims of capture. -

Archives and Special Collections

Archives and Special Collections Dickinson College Carlisle, PA COLLECTION REGISTER Name: Price, Eli Kirk (1797-1884) MC 1999.13 Material: Family Papers (1797-1937) Volume: 0.75 linear feet (Document Boxes 1-2) Donation: Gift of Samuel and Anna D. Moyerman, 1965 Usage: These materials have been donated without restrictions on usage. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Eli Kirk Price was born near Brandywine in Chester County, Pennsylvania on July 20, 1797. He was the eighth of eleven children born to Rachel and Philip Price, members of the Society of Friends. Young Eli was raised within the Society and received his education at Westtown Boarding School in West Chester, Pennsylvania. After his years at Westtown, Price obtained his first business instruction in the store of John W. Townsend of West Chester. In 1815 Price went on to the countinghouse of Thomas P. Cope of Philadelphia, a shipping merchant in the Liverpool trade. While in the employ of Cope, Price familiarized himself with mercantile law and became interested in real estate law. In 1819 he began his legal studies under the tutelage of the prominent lawyer, John Sergeant of Philadelphia, and he was admitted to the Philadelphia Bar on May 28, 1822. On June 10, 1828 Price married Anna Embree, the daughter of James and Rebecca Embree. Together Eli and Anna had three children: Rebecca E. (Mrs. Hanson Whithers), John Sergeant, and Sibyl E (Mrs. Starr Nicholls). Anna Price died on June 4, 1862, a year and a half after their daughter Rebecca had died in January 1861. Price’s reputation as one of Philadelphia’s leading real estate attorneys led to his involvement in politics. -

History Overview Detailed 2020-2021 Tri 2

TRIMESTERTRIMESTER 2 HISTORYHISTORY OVERVIEWOVERVIEW 2020-2021 1/4-1/4-1/1/77 The Constitution Date 1787 Themes Rise and Fall of Empires and Nations Trade and Commerce Readings 1/4-5 Hist US V3 Ch 35, 36 Shhh! p 7-26 1/6-7 Hist US V3 Ch 37, 38 Shhh! p 28-44 1/11-12 Hist US V3 Ch 39, 40 Who Was Geo Washington? pp 1-21 Founding Mothers – Mrs. Jay Story of George Washington Ch 1-2 1/13-14 Hist US V3 Ch 41, 42 Who Was Geo Washington? pp 22-42 Story of George Washington Ch 3-4 BriefBrief OverviewOverview ofof AmericaAmerica inin thethe AftermathAftermath ofof thethe RevolutionaryRevolutionary WarWar The state of American affairs post-Revolutionary War: Congress and the states are in debt, and a postwar depression on the scale of the Great Depression of the 1930s exacerbates the troubles. Currency is losing value. Army vets are unpaid – given promissory notes that are worth little due to inflation. Vets sell their notes to put clothes on their backs and food in their mouths. Economic slump of the 1780s had many sources: • Massive quantities of property were destroyed in the war. • Because men were fighting in the war, they were unable to perform their regular jobs. Economic output fell. • Enslaved men, women, and children emancipated themselves by leaving with the British or simply running into forests and swamps. This was a financial loss to their enslavers. • Britain refused to allow Americans to trade with British sugar islands in the Caribbean – one of the American’s greatest income sources. -

History: Past and Present

CHAPTER 4 History: Past and Present Cumberland County has a rich history that continues to contribute to the heritage and identity of the county today. Events in the past have shaped the county as it has evolved over time. It is important to understand and appreciate the past in order to plan for the future. Historical Development Cumberland County's origin began in 1681 with the land grant to William Penn by King Charles II of England. Westward colonial expansion produced a flow of settlers into the Cumberland Valley, including many Scotch-Irish. James Letort established a trading post along the present-day Letort Spring Run in 1720. Prior to the American Revolution, large numbers of German emigrants moved into the area. The increasing number of settlers required the need for a more central governmental body to provide law and order. At that time, Lancaster City was the nearest seat of government to the Cumberland Valley. Through the Act of January 27, 1750, Governor James Hamilton directed the formation of Cumberland County (named after Cumberland County, England) as the sixth county erected in the Commonwealth. Its boundaries extended from the Susquehanna River and York County on the east to Maryland on the south, to the border of Pennsylvania on the west, and to central Pennsylvania on the north. Shippensburg was established as the county seat and the first courts were held there in 1750 – 51. The county seat was moved to Carlisle in 1752. Other counties were later formed from Cumberland County, including Bedford (1771), Northumberland (1772), Franklin (1784), Mifflin (1789), and Perry (1820). -

Viewed Them As Pawns in a Political Game

© 2006 ANGELA M. ZOMBEK ALL RIGHTS RESERVED CAMP CHASE AND LIBBY PRISONS: A STUDY OF POWER AND RESISTANCE ON THE NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN HOME FRONTS 1863-1864 A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of the University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of the Arts Angela M. Zombek August, 2006 CAMP CHASE AND LIBBY PRISONS: AN EXAMINATION OF POWER AND RESISTANCE ON THE NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN HOME FRONTS 1863-1864 Angela M. Zombek Thesis Approved: Accepted: Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Lesley J. Gordon Dr. Ronald Levant Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Tracey Jean Boisseau Dr. George Newkome Department Chair Date Dr. Constance Bouchard ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………….... 1 II. HISTORY OF CAMP CHASE………………………………………………14 III. BENEATH THE SURFACE – UNDERCUTTING THEORETICAL POWER……………………………………………………………………. 22 IV. HISTORY OF LIBBY PRISON……………………………………………. 45 V. FREEDOM AND CONFINEMENT: THE POLITICS AND POWER OF SPACE…………………………………………………………………….. 56 VI. CONCLUSION……………………………………………………………... 91 BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………... 96 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A patriotic fervor swept the divided nation when the American Civil War broke out in April of 1861. Northerners and Southerners hastily prepared for a war that would surely end within a few months. Union and Confederate politicians failed to foresee four years of bloody conflict, nor did they expect to confront the massive prisoner of war crisis that this war generated. During the years 1861-1865, Union and Confederate officials held a combined 409,608 Americans as prisoners of war.1 The prisoner of war crisis is a significant part of Civil War history. However, historians have largely neglected the prison camps, and the men they held. -

Martin's Bench and Bar of Philadelphia

MARTIN'S BENCH AND BAR OF PHILADELPHIA Together with other Lists of persons appointed to Administer the Laws in the City and County of Philadelphia, and the Province and Commonwealth of Pennsylvania BY , JOHN HILL MARTIN OF THE PHILADELPHIA BAR OF C PHILADELPHIA KKKS WELSH & CO., PUBLISHERS No. 19 South Ninth Street 1883 Entered according to the Act of Congress, On the 12th day of March, in the year 1883, BY JOHN HILL MARTIN, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. W. H. PILE, PRINTER, No. 422 Walnut Street, Philadelphia. Stack Annex 5 PREFACE. IT has been no part of my intention in compiling these lists entitled "The Bench and Bar of Philadelphia," to give a history of the organization of the Courts, but merely names of Judges, with dates of their commissions; Lawyers and dates of their ad- mission, and lists of other persons connected with the administra- tion of the Laws in this City and County, and in the Province and Commonwealth. Some necessary information and notes have been added to a few of the lists. And in addition it may not be out of place here to state that Courts of Justice, in what is now the Com- monwealth of Pennsylvania, were first established by the Swedes, in 1642, at New Gottenburg, nowTinicum, by Governor John Printz, who was instructed to decide all controversies according to the laws, customs and usages of Sweden. What Courts he established and what the modes of procedure therein, can only be conjectur- ed by what subsequently occurred, and by the record of Upland Court. -

Afua Cooper, "Ever True to the Cause of Freedom – Henry Bibb

Ever True to the Cause of Freedom Henry Bibb: Abolitionist and Black Freedom’s Champion, 1814-1854 Afua Cooper Black abolitionists in North America, through their activism, had a two-fold objective: end American slavery and eradicate racial prejudice, and in so doing promote race uplift and Black progress. To achieve their aims, they engaged in a host of pursuits that included lecturing, fund-raising, newspaper publishing, writing slave narratives, engaging in Underground Railroad activities, and convincing the uninitiated to do their part for the antislavery movement. A host of Black abolitionists, many of whom had substantial organizational experience in the United States, moved to Canada in the three decades stretching from 1830 to 1860. Among these were such activists as Henry Bibb, Mary Bibb, Martin Delany, Theodore Holly, Josiah Henson, Mary Ann Shadd, Samuel Ringgold Ward, J.C. Brown and Amelia Freeman. Some like Henry Bibb were escaped fugitive slaves, others like J.C. Brown had bought themselves out of slavery. Some like Amelia Freeman and Theodore Holly were free-born Blacks. None has had a more tragic past however than Henry Bibb. Yet he would come to be one of the 19th century’s foremost abolitionists. At the peak of his career, Bibb migrated to Canada and made what was perhaps his greatest contribution to the antislavery movement: the establishment of the Black press in Canada. This discussion will explore Bibb’s many contributions to the Black freedom movement but will provide a special focus on his work as a newspaper founder and publisher. Henry Bibb was born in slavery in Kentucky around 1814.1 Like so many other African American slaves, Bibb’s parentage was biracial. -

Download the Fall 2016 Issue (PDF)

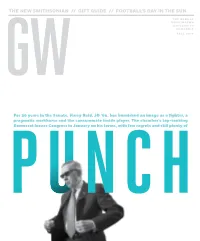

THE NEW SMITHSONIAN // GIFT GUIDE // FOOTBALL’S DAY IN THE SUN THE GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE FALL 2016 For 30 years in the Senate, Harry Reid, JD ’64, has burnished an image as a fighter, a pragmatic workhorse and the consummate inside player. The chamber’s top-ranking Democrat leaves Congress in January on his terms, with few regrets and still plenty of gw magazine / Fall 2016 GW MAGAZINE FALL 2016 A MAGAZINE FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS CONTENTS [Features] 26 / Rumble & Sway After 30 years in the U.S. Senate—and at least as many tussles as tangos—the chamber’s highest-ranking Democrat, Harry Reid, JD ’64, prepares to make an exit. / Story by Charles Babington / / Photos by Gabriella Demczuk, BA ’13 / 36 / Out of the Margins In filling the Smithsonian’s new National Museum of African American History and Culture, alumna Michèle Gates Moresi and other curators worked to convey not just the devastation and legacy of racism, but the everyday experience of black life in America. / By Helen Fields / 44 / Gift Guide From handmade bow ties and DIY gin to cake on-the-go, our curated selection of alumni-made gifts will take some panic out of the season. / Text by Emily Cahn, BA ’11 / / Photos by William Atkins / 52 / One Day in January Fifty years ago this fall, GW’s football program ended for a sixth and final time. But 10 years before it was dropped, Colonials football rose to its zenith, the greatest season in program history and a singular moment on the national stage.