Torture in the Name of National Security: Isolated Incidents Or Covert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government Turns the Other Way As Judges Make Findings About Torture and Other Abuse

USA SEE NO EVIL GOVERNMENT TURNS THE OTHER WAY AS JUDGES MAKE FINDINGS ABOUT TORTURE AND OTHER ABUSE Amnesty International Publications First published in February 2011 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2011 Index: AMR 51/005/2011 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.2 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 Judges point to human rights violations, executive turns away ........................................... 4 Absence -

Interrogation, Detention, and Torture DEBORAH N

Finding Effective Constraints on Executive Power: Interrogation, Detention, and Torture DEBORAH N. PEARLSTEIN* INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................1255 I. EXECUTIVE POLICY AND PRACTICE: COERCIVE INTERROGATION AND T O RTU RE ....................................................................................................1257 A. Vague or Unlawful Guidance................................................................ 1259 B. Inaction .................................................................................................1268 C. Resources, Training, and a Plan........................................................... 1271 II. ExECuTrVE LIMITs: FINDING CONSTRAINTS THAT WORK ...........................1273 A. The ProfessionalM ilitary...................................................................... 1274 B. The Public Oversight Organizationsof Civil Society ............................1279 C. Activist Federal Courts .........................................................................1288 CONCLUSION ........................................................................................................1295 INTRODUCTION While the courts continue to debate the limits of inherent executive power under the Federal Constitution, the past several years have taught us important lessons about how and to what extent constitutional and sub-constitutional constraints may effectively check the broadest assertions of executive power. Following the publication -

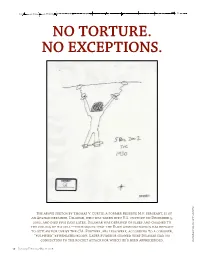

No Torture. No Exceptions

NO TORTURE. NO EXCEPTIONS. The above sketch by Thomas V. Curtis, a former Reserve M.P. sergeant, is of New York Times an Afghan detainee, Dilawar, who was taken into U.S. custody on December 5, 2002, and died five days later. Dilawar was deprived of sleep and chained to the ceiling of his cell—techniques that the Bush administration has refused to outlaw for use by the CIA. Further, his legs were, according to a coroner, “pulpified” by repeated blows. Later evidence showed that Dilawar had no connection to the rocket attack for which he’d been apprehended. A sketch by Thomas Curtis, V. a Reserve M.P./The 16 January/February/March 2008 Introduction n most issues of the Washington Monthly, we favor ar- long-term psychological effects also haunt patients—panic ticles that we hope will launch a debate. In this issue attacks, depression, and symptoms of post-traumatic-stress Iwe seek to end one. The unifying message of the ar- disorder. It has long been prosecuted as a crime of war. In our ticles that follow is, simply, Stop. In the wake of Septem- view, it still should be. ber 11, the United States became a nation that practiced Ideally, the election in November would put an end to torture. Astonishingly—despite the repudiation of tor- this debate, but we fear it won’t. John McCain, who for so ture by experts and the revelations of Guantanamo and long was one of the leading Republican opponents of the Abu Ghraib—we remain one. As we go to press, President White House’s policy on torture, voted in February against George W. -

Usa Amnesty International's Supplementary Briefing To

AI Index: AMR 51/061/2006 3 May 2006 USA AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL’S SUPPLEMENTARY BRIEFING TO THE UN COMMITTEE AGAINST TORTURE This briefing includes further information on the implementation by the United States of America (USA) of its obligations under the UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (Convention; UN Convention against Torture), with regard to the forthcoming consideration by the UN Committee Against Torture (the Committee) of the USA’s second periodic report.(1) The briefing updates Amnesty International’s concerns with regard to US "war on terror" detention, interrogation and related policies, as outlined in its preliminary briefing of August 2005, and provides additional information on domestic policies and practice. US OBLIGATIONS UNDER THE CONVENTION WITH RESPECT TO DETAINEES HELD IN THE CONTEXT OF THE "WAR ON TERROR" 1. General supplementary observations on definitions of torture and use of torture under interrogation, including deaths in custody (Articles 1 and 16) Evidence continues to emerge of widespread torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment of detainees held in US custody in Afghanistan, Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, Iraq and other locations. While the government continues to assert that abuses resulted for the most part from the actions of a few "aberrant" soldiers and lack of oversight, there is clear evidence that much of the ill-treatment has stemmed directly from officially santioned procedures and policies, including interrogation techniques approved by Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld for use in Guantánamo and later exported to Iraq.(2) While it seems that some practices, such as "waterboarding", were reserved for high value detainees, others appear to have been routinely applied during detentions and interrogations in Afghanistan, Guantánamo and Iraq. -

GUANTANAMO BAY and OMAR KHADR Introduction

GUANTANAMO BAY AND OMAR KHADR Introduction On July 27, 2002, a U.S. military unit by Osama bin Laden, was responsible Focus on patrol near Khost, in Afghanistan, for the terrorist attacks on New This News in Review story focuses on the stormed a bunker containing a band of York City and Washington, D.C., on case of Omar Khadr, Al Qaeda fighters operating in support September 11, 2001. Khadr’s father, a the young Canadian of Taliban insurgents fighting the NATO native of Egypt, moved the family to who has been held occupation of the country. In the ensuing Afghanistan in the 1990s, where he in the U.S. military firefight and bombing, three insurgents ran a charity organization for orphans. prison in Guantanamo and one American soldier were killed. As He strongly supported the extremist Bay, Cuba, since 2002 the dead and wounded Al Qaeda fighters Taliban regime then ruling the country and the controversy surrounding his were dragged from the bombed-out and was a personal friend of bin Laden. detention there and ruins of their compound, the U.S. troops He encouraged his four sons—Omar, possible release. were astonished to discover that one of Abdurahman, Abdullah and Abdul—to them, a 15-year-old boy, was a Canadian undergo training as jihadists, or Islamic who spoke perfect English. His name holy warriors, against the United States. Did you know . was Omar Khadr, and his subsequent Omar became separated from his father Omar Khadr would have most likely died detention as an alleged “unlawful after the fall of the Taliban during the on the battlefield enemy combatant” in the U.S. -

ANNEX a Some Publicly Known Deaths of Detainees in U.S

ANNEX A Some Publicly Known Deaths of Detainees in U.S. Custody in Afghanistan and Iraq ACLU-RDI 6826 p.1 Annex A: Some Publicly Known Deaths of Detainees in U.S. Custody in 1 Afghanistan and Iraq No. Name Location Cause of Circumstances Surrounding Death and Date Death 1. Mohammed Near Lwara, Death by Blunt Army Criminal Investigation Division found Sayari Afghanistan Force Injuries probable cause to believe that the commander and Aug. 28, 2002 three other members of Operational Detachment- Alpha 343, 3rd Special Forces Group, had committed the offenses of murder and conspiracy when they lured Mohamed Sayari, an Afghan civilian, into a roadblock, detained him, and killed him. Investigation further found probable cause to believe that a fifth Special Forces soldier had been an accessory after the fact and that the team's commander had instructed a soldier to destroy incriminating photographs of Sayari’s body. No court-martial or Article 32 hearing was convened. One soldier was given a written reprimand. None of the others received any punishment at all.2 2. Name Kabul, Death by The CIA was reportedly involved in the killing of a unknown Afghanistan Hypothermia detainee in Afghanistan. A CIA case officer at the Nov. 2002 “Salt Pit,” a secret U.S.-run prison just north of Kabul, ordered guards to “strip naked an uncooperative young Afghan detainee, chain him to the concrete floor and leave him there overnight without blankets,” the Washington Post reported after interviewing four government officials familiar with the case. According to the article, Afghan guards “paid by the CIA and working under CIA supervision” dragged the prisoner around the concrete floor of the facility, “bruising and scraping his skin,” before placing him in a cell for the night without clothes. -

The Fundamental Paradoxes of Modern Warfare in Al Maqaleh V

PAINTING OURSELVES INTO A CORNER: THE FUNDAMENTAL PARADOXES OF MODERN WARFARE IN AL MAQALEH V. GATES Ashley C. Nikkel* See how few of the cases of the suspension of the habeas corpus law, have been worthy of that suspension. They have been either real treason, wherein the parties might as well have been charged at once, or sham plots, where it was shameful they should ever have been suspected. Yet for the few cases wherein the suspension of the habeas corpus has done real good, that operation is now become habitual and the minds of the nation almost prepared to live under its constant suspension.1 INTRODUCTION On a cold December morning in 2002, United States military personnel entered a small wire cell at Bagram Airfield, in the Parwan province of Afghan- istan. There, they found Dilawar, a 20-year-old Afghan taxi driver, hanging naked and dead from the ceiling.2 The air force medical examiner who per- formed Dilawar’s autopsy reported his legs had been beaten so many times the tissue was “falling apart” and “had basically been pulpified.”3 The medical examiner ruled his death a homicide, the result of an interrogation lasting four days as Dilawar stood naked, his arms shackled over his head while U.S. inter- rogators performed the “common peroneal strike,” a debilitating blow to the side of the leg above the knee.4 The U.S. military detained Dilawar because he * J.D. Candidate, 2012, William S. Boyd School of Law, Las Vegas; B.A., 2009, University of Nevada, Reno. The Author would like to thank Professor Christopher L. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE April 03, 2006 Paper Awaits Court Decision on Guantanamo Detainee By HoldtheFrontPage staff The Argus in Brighton is waiting to hear if its campaign for a fair trial for a local man detained at Guantanamo Bay has been successful. The paper is calling on the Government to intervene in the case of Omar Deghayes, and a judicial review has been held to determine whether Foreign Secretary Jack Straw should be ordered to seek his release. Omar's lawyers argued that the Government has a legal and moral responsibility to step in, but it disagrees as he is not a British citizen. Judgement has been reserved as a decision is expected this week. The Argus took up Omar's fight last year, and delivered a dossier to Home Secretary Charles Clarke. He and his family were granted asylum by the UK Government nearly 20 years ago and his home was in Saltdean, Brighton. The dossier included a letter from The Argus' editor Michael Beard, who said: "We believe Mr Deghayes' continued incarceration by the US breaches Article 10 of the Universal Declaration of the Human Rights which states: Everyone is entitled in full equality to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal, in the determination of his rights and obligations and of any criminal charge against him. "We therefore believe the Government has a duty to lobby the US to charge Mr Deghayes and put him on trial, in accordance with international law, or free him immediately." http://www.cageprisoners.com/articles.php?id=13200 SOURCE: Holdthefrontpage.co.uk Omar Khadr Faces New Hearing BETH GORHAM CANADIAN PRESS Canadian teenager Omar Khadr will once again appear at an American military tribunal this week, even as the U.S. -

Securitization Theory and the Canadian Construction of Omar Khadr

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2018-05-18 Securitization Theory and the Canadian Construction of Omar Khadr Pirnie, Elizabeth Irene Pirnie, E. I. (2018). Securitization Theory and the Canadian Construction of Omar Khadr (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/31940 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/106673 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Securitization Theory and the Canadian Construction of Omar Khadr by Elizabeth Irene Pirnie A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMMUNICATION AND MEDIA STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA May, 2018 © Elizabeth Irene Pirnie 2018 ii Abstract While the provision of security and protection to its citizens is one way in which sovereign states have historically claimed legitimacy (Nyers, 2004: 204), critical security analysts point to security at the level of the individual and how governance of a nation’s security underscores the state’s inherently paradoxical relationship to its citizens. Just as the state may signify the legal and institutional structures that delimit a certain territory and provide and enforce the obligations and prerogatives of citizenship, the state can equally serve to expel and suspend modes of legal protection and obligation for some (Butler and Spivak, 2007). -

Case No. 2300/12/67 JOINT EXPERT OPINION By: Katherine Gallagher Senior Staff Attorney Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR)

IN THE COUR D’APPEL DE PARIS TRIBUNAL DE GRANDE INSTANCE DE PARIS Case No. 2300/12/67 JOINT EXPERT OPINION by: Katherine Gallagher Senior Staff Attorney Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), New York Wolfgang Kaleck General Secretary European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), Berlin 7 November 2019 I. INTRODUCTION The Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) and the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) present this dossier containing key information regarding the role played by DONALD H. RUMSFELD, the former U.S. Secretary of Defense, in the torture and other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment of detainees held in U.S. custody in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. An extensive investigation in 2008 by the U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services into the treatment of detainees in U.S. custody at Guantánamo Bay concluded that The abuse of detainees in U.S. custody cannot simply be attributed to the actions of a “few bad apples” acting on their own. The fact is that senior officials in the United States government solicited information on how to use aggressive techniques, redefined the law to create the appearance of their legality, and authorized their use against detainees.1 The U.S Senate Committee on Armed Services concluded that torture was official Department of Defense (DoD) policy. This dossier sets out RUMSFELD’s individual responsibility for this policy, detailing the role RUMSFELD played in the torture of detainees captured in the “war on terror” and detained at Guantánamo Bay as well as other locations. It describes how RUMSFELD oversaw the introduction of and approved the use of abusive interrogation techniques. -

United States District Court District of Connecticut

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF CONNECTICUT Arkan Mohammed ALI, Thahe Mohammed SABBAR, Sherzad Kamal KHALID and Ali H., Case No. ______________ Plaintiffs, v. Date: March 1, 2005 Thomas PAPPAS, Defendant. COMPLAINT FOR DECLARATORY RELIEF AND DAMAGES I. INTRODUCTION 1. Plaintiffs are individuals who were incarcerated in U.S. detention facilities in Iraq where they were subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, including severe and repeated beatings, cutting with knives, sexual humiliation and assault, confinement in a wooden box, forcible sleep and sensory deprivation, mock executions, death threats, and restraint in contorted and excruciating positions. 2. The Plaintiffs, Arkan Mohammed Ali, Thahe Mohammed Sabbar, Sherzad Kamal Khalid and Ali H., are among the unknown number of U.S. detainees in Iraq who have suffered torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. 3. Plaintiffs bring this action against Defendant Colonel Thomas Pappas of the U.S. Army, who commanded U.S. military intelligence and military police forces in Iraq during the time Plaintiffs were detained and tortured. Defendant Pappas’ policies, patterns, practices, derelictions of duty and command failures caused Plaintiffs’ abuse. Defendant Pappas bears responsibility for the physical and psychological injuries that Plaintiffs have suffered. - 1 - 402388.1 4. Official government reports have documented, and military officials have acknowledged, many of the horrific abuses inflicted on detainees in U.S. custody. Such torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment of detainees in U.S. custody violates the United States Constitution, U.S.-ratified treaties including the Geneva Conventions, military rules and guidelines, the law of nations, and our fundamental moral values as a nation. -

Case 1:08-Cv-00827-GBL-JFA Document 254 Filed 04/04/13 Page 1 of 55 Pageid# 3263

Case 1:08-cv-00827-GBL-JFA Document 254 Filed 04/04/13 Page 1 of 55 PageID# 3263 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR TilE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA SUIIAIL NAJIM. ABDULLAII AL SHIMARI ) CIVIL ACTION TAHA YASEEN ARRAQ RASII1D ) NO. 08-cv-0827 GBL-JFA ASAAI) IIAMZA FIANFOOSI'I AL-ZUBA'E CIVIL COMPLAINT SALAEI LIASAN NSAIF JASIM AT.,-EJAILI JURY DEMAND Plaintiffs, REDACTEI) PUBLIC VERSION V. CAC PREMIER TECHNOLOGY, INC. 11 00 North (ilchc Road Arlington, Virginia 22201 Defendant. THIRD AMENDED COMPLAINT Plaintiffs are thur Iraqi civilians who were victims of the Abu Ghraib prison abuse scandal. As was well-publicized in the spring of 2004, detainees at the "Hard Site" within Abe Ghraib prison were brutally tortured and otherwise seriously abused by persons conspiring and otherwise acting together. Included among the conspirators inflicting severe pain on Plaintiffs were employees of a defense contractor commonly known as "CAC." Indeed, according to testimony and statements by military co-conspirators, CACI employees Steven Stcfiinowicz (commonly known as "Big Steve"), Daniel Johnson (commonly known as "DJ") and Timothy Dugan directed and caused much of the egregious torture and abuse at Abu Ghraib. JURISDICTION AND VENUE 2. This Court has original jurisdiction over the subject matter of this action pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1331 (federal question); 28 U.S.C. § 1332 (diversity jurisdiction); 28 U.S.C. § 1350 (Alien Tort Statute); and 28 U.S.C. § 1367 (supplemental jurisdiction). 6053919v.i Case 1:08-cv-00827-GBL-JFA Document 254 Filed 04/04/13 Page 2 of 55 PageID# 3264 3.