Securitization Theory and the Canadian Construction of Omar Khadr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

Omar Khadr: Mobilizing Ideology and the Decline of Citizenship in the Age of Terrorism by Brittany Sherwood B.A. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Legal Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2010, Brittany Sherwood Library and Archives Bibliothèque et ?F? Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-71720-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-71720-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Government Turns the Other Way As Judges Make Findings About Torture and Other Abuse

USA SEE NO EVIL GOVERNMENT TURNS THE OTHER WAY AS JUDGES MAKE FINDINGS ABOUT TORTURE AND OTHER ABUSE Amnesty International Publications First published in February 2011 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2011 Index: AMR 51/005/2011 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.2 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 Judges point to human rights violations, executive turns away ........................................... 4 Absence -

Report on Public Forum

Anti-Terrorism and the Security Agenda: Impacts on Rights, Freedoms and Democracy Report and Recommendations for Policy Direction of a Public Forum organized by the International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group Ottawa, February 17, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................2 ABOUT THE ICLMG .............................................................................................................2 BACKGROUND .....................................................................................................................3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................................................................4 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR POLICY DIRECTION ..........................................................14 PROCEEDINGS......................................................................................................................16 CONCLUDING REMARKS...................................................................................................84 ANNEXES...............................................................................................................................87 ANNEXE I: Membership of the ICLMG ANNEXE II: Program of the Public Forum ANNEXE III: List of Participants/Panelists Anti-Terrorism and the Security Agenda: Impacts on Rights Freedoms and Democracy 2 __________________________________________________________________________________ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Forum session reporting -

Interrogation, Detention, and Torture DEBORAH N

Finding Effective Constraints on Executive Power: Interrogation, Detention, and Torture DEBORAH N. PEARLSTEIN* INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................1255 I. EXECUTIVE POLICY AND PRACTICE: COERCIVE INTERROGATION AND T O RTU RE ....................................................................................................1257 A. Vague or Unlawful Guidance................................................................ 1259 B. Inaction .................................................................................................1268 C. Resources, Training, and a Plan........................................................... 1271 II. ExECuTrVE LIMITs: FINDING CONSTRAINTS THAT WORK ...........................1273 A. The ProfessionalM ilitary...................................................................... 1274 B. The Public Oversight Organizationsof Civil Society ............................1279 C. Activist Federal Courts .........................................................................1288 CONCLUSION ........................................................................................................1295 INTRODUCTION While the courts continue to debate the limits of inherent executive power under the Federal Constitution, the past several years have taught us important lessons about how and to what extent constitutional and sub-constitutional constraints may effectively check the broadest assertions of executive power. Following the publication -

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002

Description of document: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002 Requested date: 2002 Release date: 2003 Posted date: 08-February-2021 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 Filing a FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1 O ct 2000_30 April 2002 Creation Date Requester Last Name Case Subject 36802.28679 STRANEY TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH OF INDIA; HONG KONG; CHINA AND WTO 36802.2992 CRAWFORD EIGHT DIFFERENT REQUESTS FOR REPORTS REGARDING CIA EMPLOYEES OR AGENTS 36802.43927 MONTAN EDWARD GRADY PARTIN 36802.44378 TAVAKOLI-NOURI STEPHEN FLACK GUNTHER 36810.54721 BISHOP SCIENCE OF IDENTITY FOUNDATION 36810.55028 KHEMANEY TI LEAF PRODUCTIONS, LTD. -

Journal of Prisoners on Prisons 26(1-2)

Beaver Creek Institution Anonymous Prisoner 11 he reason I am contributing to this Dialogue on penal reform in Canada Tis because I am in my sixties and my crime was an isolated incident, resulting in a sentence for second degree murder in the 1990s. I did 15 years inside as a model prisoner and was paroled in 2008 to a halfway house. Once there, I spent two years in the community without incident and was subsequently given full parole. However, in 2013, I was revoked for a negative urine sample. I have been back inside since, incurring unnecessary costs to taxpayers as my breach did not constitute a danger or threat to the public. Prior to my incarceration, I was never a burden on society. With several skilled trades under my belt, I owned a home and business. Ever since Harper’s ‘tough on crime’ and ‘life means life’ approach to imprisonment, a lot of us Lifers were revoked with no new criminal charges and with no help from our parole offi cers. This leaves us with no light at the end of the tunnel. There should be a time limit that restricts revoking parolees who have committed no new crimes once they have completed a signifi cant portion of time under supervised release. 147 Beaver Creek Institution Anonymous Prisoners aving served more than a decade in federal penitentiaries, I have seen Hmany things change for the worse. Below, is a list of recommendations that a number of us at Beaver Creek Minimums who meet regularly to discuss how we can atone for our actions with our victims and communities compiled during one of our meetings. -

Mass Guantanamo Suicide Protest

BBC NEWS | World | Americas | Mass Guantanamo suicide protest http://newsvote.bbc.co.uk/mpapps/pagetools/print/news.bbc.co.... Mass Guantanamo suicide protest Twenty-three prisoners tried to hang or strangle themselves during a mass protest at Guantanamo Bay in 2003, the US military has revealed. The action took place during a period of several days in August that year, the military said in a statement. A spokesman said the incidents were "gestures" aimed at getting attention, and only two of the prisoners were considered suicidal. Officials would not say why they had not previously reported the incident. The detention centre at the US base in Cuba currently holds about 550 detainees. They are mostly suspected Taleban and al-Qaeda fighters captured during the war in Afghanistan, many of whom have been held for more than three years without charge or access to lawyers. The last four British men held at Guantanamo Bay are expected back in the UK on Tuesday, after almost three years in US custody. Moazzam Begg, Martin Mubanga, Richard Belmar and Feroz Abbasi are expected to be questioned under UK anti-terror laws after their return. The US agreed the men could be released after "complex" talks with the UK. Transferred A total of 23 prisoners tried to hang or strangle themselves in their cells from 18 to 26 August 2003, the US Southern Command in Miami, which covers Guantanamo, said in a statement on Monday. There were 10 such cases on 22 August alone, the military said. However, only two of the 23 prisoners were considered to be attempting suicide. -

Anatomy of a Modern Homegrown Terror Cell: Aabid Khan Et Al

Anatomy of a Modern Homegrown Terror Cell: Aabid Khan et al. (Operation Praline) Evan F. Kohlmann NEFA Senior Investigator September 2008 In June 2006, a team of British law enforcement units (led by the West Yorkshire Police) carried out a series of linked arrests in the cities of London, Manchester, Bradford, and Dewsbury in the United Kingdom. The detained suspects in the investigation known as “Operation Praline” included 22-year old British national Aabid Hussain Khan; 21-year old British national Sultan Mohammed; and 16-year old British national Hammaad Munshi. All of the men would later be indicted by the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) for violations of Section 57 of the U.K. Anti- Terrorism, Crime, and Security Act of 2001. In August 2008, following a jury trial at Blackfriars Crown Court in London, Khan, Mohammed, and Munshi were found guilty of charges that included possessing an article for a purpose connected with the commission, preparation, or instigation of an act of terrorism, and making a record of information likely to be useful in terrorism. Khan and Mohammed were each sentenced, respectively, to 12 and 10-year prison terms. According to Karen Jones, the reviewing lawyer in the case from the U.K. Crown Prosecution Service Counter Terrorism Division, “The evidence showed Khan was a committed and active supporter of Al Qaida ideology. He had extensive amounts of the sort of information that a terrorist would need and use and the international contacts to pass it on… Aabid Khan was very much the ‘Mr. Fix-it’ of the group. -

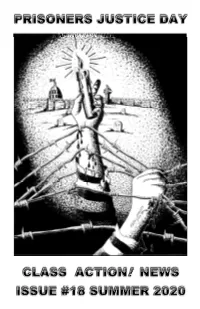

Class Action News Issue #18 Summer 2020

- 1 - 2 > CAN-#18 < Editor’s Note > < Contents > It is Summer & Issue #18 News …………………………... 3-12 of ‘Class Action News’. Health & Harm Reduction …..…... 13 This magazine is by & for Resources ………….……….... 14-16 the Prisoner Class in Canada. < Artists in this Issue > In every Issue we provide a safe space for creative expression and literacy development. Cover: Pete Collins These zines feature art, poetry, stories, news, observations, concerns, and anything of interest to share. Health & Harm Reduction info will always be provided - Yes, Be Safe! Quality & Quantity: Items printed are those that are common for diverse readers, so no religious items please. < Funding for this Issue > Artwork: Black pen (tat-style) works the best. Cover Artist will receive a $25 donation. Very special thanks to: Writings: only short poems, news, stories, … Groundswell Community Justice Trust Fund! Items selected are those that fit nicely & allow space for others (½ page = 325 words max). < Ancestral Territorial Acknowledgment > For author protection, letters & story credits will all be 'Anonymous'. We respectfully acknowledge that the land on which Prison Free Press operates is the ‘Class Action News' is published 4 times a Traditional Territory of the Wendat, the year & is free for prisoners in Canada. Anishnaabeg, Haudenosaunee, and the If you are on the outside or an organization, Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation. please send a donation. We do not have any funding so it really helps to get this inside! e ‘Dish With One Spoon’ Treaty f Editor: Tom Jackson Canadian Charter of Rights & Freedoms Publication: Class Action News Publisher: PrisonFreePress.org • The right of life, liberty and security of person PO Box 39, Stn P (Section 7). -

The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: an Empirical Study

© Reuters/HO Old – Detainees at XRay Camp in Guantanamo. The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empirical Study Benjamin Wittes and Zaahira Wyne with Erin Miller, Julia Pilcer, and Georgina Druce December 16, 2008 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 The Public Record about Guantánamo 4 Demographic Overview 6 Government Allegations 9 Detainee Statements 13 Conclusion 22 Note on Sources and Methods 23 About the Authors 28 Endnotes 29 Appendix I: Detainees at Guantánamo 46 Appendix II: Detainees Not at Guantánamo 66 Appendix III: Sample Habeas Records 89 Sample 1 90 Sample 2 93 Sample 3 96 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study EXECUTIVE SUMMARY he following report represents an effort both to document and to describe in as much detail as the public record will permit the current detainee population in American T military custody at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Station in Cuba. Since the military brought the first detainees to Guantánamo in January 2002, the Pentagon has consistently refused to comprehensively identify those it holds. While it has, at various times, released information about individuals who have been detained at Guantánamo, it has always maintained ambiguity about the population of the facility at any given moment, declining even to specify precisely the number of detainees held at the base. We have sought to identify the detainee population using a variety of records, mostly from habeas corpus litigation, and we have sorted the current population into subgroups using both the government’s allegations against detainees and detainee statements about their own affiliations and conduct. -

GUANTANAMO BAY and OMAR KHADR Introduction

GUANTANAMO BAY AND OMAR KHADR Introduction On July 27, 2002, a U.S. military unit by Osama bin Laden, was responsible Focus on patrol near Khost, in Afghanistan, for the terrorist attacks on New This News in Review story focuses on the stormed a bunker containing a band of York City and Washington, D.C., on case of Omar Khadr, Al Qaeda fighters operating in support September 11, 2001. Khadr’s father, a the young Canadian of Taliban insurgents fighting the NATO native of Egypt, moved the family to who has been held occupation of the country. In the ensuing Afghanistan in the 1990s, where he in the U.S. military firefight and bombing, three insurgents ran a charity organization for orphans. prison in Guantanamo and one American soldier were killed. As He strongly supported the extremist Bay, Cuba, since 2002 the dead and wounded Al Qaeda fighters Taliban regime then ruling the country and the controversy surrounding his were dragged from the bombed-out and was a personal friend of bin Laden. detention there and ruins of their compound, the U.S. troops He encouraged his four sons—Omar, possible release. were astonished to discover that one of Abdurahman, Abdullah and Abdul—to them, a 15-year-old boy, was a Canadian undergo training as jihadists, or Islamic who spoke perfect English. His name holy warriors, against the United States. Did you know . was Omar Khadr, and his subsequent Omar became separated from his father Omar Khadr would have most likely died detention as an alleged “unlawful after the fall of the Taliban during the on the battlefield enemy combatant” in the U.S. -

The Search for the "Manchurian Candidate" the Cia and Mind Control

THE SEARCH FOR THE "MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE" THE CIA AND MIND CONTROL John Marks Allen Lane Allen Lane Penguin Books Ltd 17 Grosvenor Gardens London SW1 OBD First published in the U.S.A. by Times Books, a division of Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Co., Inc., and simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Ltd, 1979 First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 1979 Copyright <£> John Marks, 1979 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner ISBN 07139 12790 jj Printed in Great Britain by f Thomson Litho Ltd, East Kilbride, Scotland J For Barbara and Daniel AUTHOR'S NOTE This book has grown out of the 16,000 pages of documents that the CIA released to me under the Freedom of Information Act. Without these documents, the best investigative reporting in the world could not have produced a book, and the secrets of CIA mind-control work would have remained buried forever, as the men who knew them had always intended. From the documentary base, I was able to expand my knowledge through interviews and readings in the behavioral sciences. Neverthe- less, the final result is not the whole story of the CIA's attack on the mind. Only a few insiders could have written that, and they choose to remain silent. I have done the best I can to make the book as accurate as possible, but I have been hampered by the refusal of most of the principal characters to be interviewed and by the CIA's destruction in 1973 of many of the key docu- ments.