Interrogation, Detention, and Torture DEBORAH N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government Turns the Other Way As Judges Make Findings About Torture and Other Abuse

USA SEE NO EVIL GOVERNMENT TURNS THE OTHER WAY AS JUDGES MAKE FINDINGS ABOUT TORTURE AND OTHER ABUSE Amnesty International Publications First published in February 2011 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2011 Index: AMR 51/005/2011 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.2 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 Judges point to human rights violations, executive turns away ........................................... 4 Absence -

Law and Military Operations in Kosovo: 1999-2001, Lessons Learned For

LAW AND MILITARY OPERATIONS IN KOSOVO: 1999-2001 LESSONS LEARNED FOR JUDGE ADVOCATES Center for Law and Military Operations (CLAMO) The Judge Advocate General’s School United States Army Charlottesville, Virginia CENTER FOR LAW AND MILITARY OPERATIONS (CLAMO) Director COL David E. Graham Deputy Director LTC Stuart W. Risch Director, Domestic Operational Law (vacant) Director, Training & Support CPT Alton L. (Larry) Gwaltney, III Marine Representative Maj Cody M. Weston, USMC Advanced Operational Law Studies Fellows MAJ Keith E. Puls MAJ Daniel G. Jordan Automation Technician Mr. Ben R. Morgan Training Centers LTC Richard M. Whitaker Battle Command Training Program LTC James W. Herring Battle Command Training Program MAJ Phillip W. Jussell Battle Command Training Program CPT Michael L. Roberts Combat Maneuver Training Center MAJ Michael P. Ryan Joint Readiness Training Center CPT Peter R. Hayden Joint Readiness Training Center CPT Mark D. Matthews Joint Readiness Training Center SFC Michael A. Pascua Joint Readiness Training Center CPT Jonathan Howard National Training Center CPT Charles J. Kovats National Training Center Contact the Center The Center’s mission is to examine legal issues that arise during all phases of military operations and to devise training and resource strategies for addressing those issues. It seeks to fulfill this mission in five ways. First, it is the central repository within The Judge Advocate General's Corps for all-source data, information, memoranda, after-action materials and lessons learned pertaining to legal support to operations, foreign and domestic. Second, it supports judge advocates by analyzing all data and information, developing lessons learned across all military legal disciplines, and by disseminating these lessons learned and other operational information to the Army, Marine Corps, and Joint communities through publications, instruction, training, and databases accessible to operational forces, world-wide. -

Chapter 1: Introduction 1

Saint Paul University The Making of Torturers: The Case of Abu Ghraib – An Exploration of Individual Psychological Factors, Group Factors, and Mimetic Structures of Violence By Nadine Olafsson A THESIS SUBMITTED to the FACULTY of GRADUATE STUDIES in PARTIAL FULFILLMENT of the REQUIREMENTS for the DEGREE of MASTER of ARTS in CONFLICT STUDIES © Nadine Olafsson, Ottawa, Canada, 2017 Abstract The exposure of the prison abuse scandal at Abu Ghraib in 2004 deeply shocked the American conscience and triggered a widespread public debate surrounding both the legitimacy of the use of torture and American values. With the election of president Trump this discussion has once more moved into the limelight of public discussion. While much attention has been devoted to the morality of torture, little has been paid to the perpetrators of torture themselves. This thesis explores the theoretical framework of Grodin and Annas (2007) to assess individual and group psychological factors in combination with Redekop’s (2002) mimetic structures of violence to assess how ordinary people turned into torturers at Abu Ghraib in 2004. The data analysed stems from the Central Investigative Departments investigation into the torture scandal, as well as the Taguba Report, the Fay Report, the Schlesinger Report, the Red Cross Report and Errol Morris award winning documentary Standard Operating Procedure. The study finds that individual and group psychological factors, in conjuncture with mimetic structures of violence appeared to have played a role in the making of torturers -

Genealogy of the Concept of Securitization and Minority Rights

THE KURD INDUSTRY: UNDERSTANDING COSMOPOLITANISM IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY by ELÇIN HASKOLLAR A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School – Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Global Affairs written under the direction of Dr. Stephen Eric Bronner and approved by ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2014 © 2014 Elçin Haskollar ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Kurd Industry: Understanding Cosmopolitanism in the Twenty-First Century By ELÇIN HASKOLLAR Dissertation Director: Dr. Stephen Eric Bronner This dissertation is largely concerned with the tension between human rights principles and political realism. It examines the relationship between ethics, politics and power by discussing how Kurdish issues have been shaped by the political landscape of the twenty- first century. It opens up a dialogue on the contested meaning and shape of human rights, and enables a new avenue to think about foreign policy, ethically and politically. It bridges political theory with practice and reveals policy implications for the Middle East as a region. Using the approach of a qualitative, exploratory multiple-case study based on discourse analysis, several Kurdish issues are examined within the context of democratization, minority rights and the politics of exclusion. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews, archival research and participant observation. Data analysis was carried out based on the theoretical framework of critical theory and discourse analysis. Further, a discourse-interpretive paradigm underpins this research based on open coding. Such a method allows this study to combine individual narratives within their particular socio-political, economic and historical setting. -

The Abu Ghraib Convictions: a Miscarriage of Justice

Buffalo Public Interest Law Journal Volume 32 Article 4 9-1-2013 The Abu Ghraib Convictions: A Miscarriage of Justice Robert Bejesky Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/bpilj Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Robert Bejesky, The Abu Ghraib Convictions: A Miscarriage of Justice, 32 Buff. Envtl. L.J. 103 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/bpilj/vol32/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Public Interest Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ABU GHRAIB CONVICTIONS: A MISCARRIAGE OF JUSTICE ROBERT BEJESKYt I. INTRODUCTION ..................... ..... 104 II. IRAQI DETENTIONS ...............................107 A. Dragnet Detentions During the Invasion and Occupation of Iraq.........................107 B. Legal Authority to Detain .............. ..... 111 C. The Abuse at Abu Ghraib .................... 116 D. Chain of Command at Abu Ghraib ..... ........ 119 III. BASIS FOR CRIMINAL CULPABILITY ..... ..... 138 A. Chain of Command ....................... 138 B. Systemic Influences ....................... 140 C. Reduced Rights of Military Personnel and Obedience to Authority ................ ..... 143 D. Interrogator Directives ................ .... -

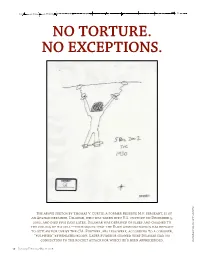

No Torture. No Exceptions

NO TORTURE. NO EXCEPTIONS. The above sketch by Thomas V. Curtis, a former Reserve M.P. sergeant, is of New York Times an Afghan detainee, Dilawar, who was taken into U.S. custody on December 5, 2002, and died five days later. Dilawar was deprived of sleep and chained to the ceiling of his cell—techniques that the Bush administration has refused to outlaw for use by the CIA. Further, his legs were, according to a coroner, “pulpified” by repeated blows. Later evidence showed that Dilawar had no connection to the rocket attack for which he’d been apprehended. A sketch by Thomas Curtis, V. a Reserve M.P./The 16 January/February/March 2008 Introduction n most issues of the Washington Monthly, we favor ar- long-term psychological effects also haunt patients—panic ticles that we hope will launch a debate. In this issue attacks, depression, and symptoms of post-traumatic-stress Iwe seek to end one. The unifying message of the ar- disorder. It has long been prosecuted as a crime of war. In our ticles that follow is, simply, Stop. In the wake of Septem- view, it still should be. ber 11, the United States became a nation that practiced Ideally, the election in November would put an end to torture. Astonishingly—despite the repudiation of tor- this debate, but we fear it won’t. John McCain, who for so ture by experts and the revelations of Guantanamo and long was one of the leading Republican opponents of the Abu Ghraib—we remain one. As we go to press, President White House’s policy on torture, voted in February against George W. -

Usa Amnesty International's Supplementary Briefing To

AI Index: AMR 51/061/2006 3 May 2006 USA AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL’S SUPPLEMENTARY BRIEFING TO THE UN COMMITTEE AGAINST TORTURE This briefing includes further information on the implementation by the United States of America (USA) of its obligations under the UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (Convention; UN Convention against Torture), with regard to the forthcoming consideration by the UN Committee Against Torture (the Committee) of the USA’s second periodic report.(1) The briefing updates Amnesty International’s concerns with regard to US "war on terror" detention, interrogation and related policies, as outlined in its preliminary briefing of August 2005, and provides additional information on domestic policies and practice. US OBLIGATIONS UNDER THE CONVENTION WITH RESPECT TO DETAINEES HELD IN THE CONTEXT OF THE "WAR ON TERROR" 1. General supplementary observations on definitions of torture and use of torture under interrogation, including deaths in custody (Articles 1 and 16) Evidence continues to emerge of widespread torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment of detainees held in US custody in Afghanistan, Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, Iraq and other locations. While the government continues to assert that abuses resulted for the most part from the actions of a few "aberrant" soldiers and lack of oversight, there is clear evidence that much of the ill-treatment has stemmed directly from officially santioned procedures and policies, including interrogation techniques approved by Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld for use in Guantánamo and later exported to Iraq.(2) While it seems that some practices, such as "waterboarding", were reserved for high value detainees, others appear to have been routinely applied during detentions and interrogations in Afghanistan, Guantánamo and Iraq. -

ANNEX a Some Publicly Known Deaths of Detainees in U.S

ANNEX A Some Publicly Known Deaths of Detainees in U.S. Custody in Afghanistan and Iraq ACLU-RDI 6826 p.1 Annex A: Some Publicly Known Deaths of Detainees in U.S. Custody in 1 Afghanistan and Iraq No. Name Location Cause of Circumstances Surrounding Death and Date Death 1. Mohammed Near Lwara, Death by Blunt Army Criminal Investigation Division found Sayari Afghanistan Force Injuries probable cause to believe that the commander and Aug. 28, 2002 three other members of Operational Detachment- Alpha 343, 3rd Special Forces Group, had committed the offenses of murder and conspiracy when they lured Mohamed Sayari, an Afghan civilian, into a roadblock, detained him, and killed him. Investigation further found probable cause to believe that a fifth Special Forces soldier had been an accessory after the fact and that the team's commander had instructed a soldier to destroy incriminating photographs of Sayari’s body. No court-martial or Article 32 hearing was convened. One soldier was given a written reprimand. None of the others received any punishment at all.2 2. Name Kabul, Death by The CIA was reportedly involved in the killing of a unknown Afghanistan Hypothermia detainee in Afghanistan. A CIA case officer at the Nov. 2002 “Salt Pit,” a secret U.S.-run prison just north of Kabul, ordered guards to “strip naked an uncooperative young Afghan detainee, chain him to the concrete floor and leave him there overnight without blankets,” the Washington Post reported after interviewing four government officials familiar with the case. According to the article, Afghan guards “paid by the CIA and working under CIA supervision” dragged the prisoner around the concrete floor of the facility, “bruising and scraping his skin,” before placing him in a cell for the night without clothes. -

The Fundamental Paradoxes of Modern Warfare in Al Maqaleh V

PAINTING OURSELVES INTO A CORNER: THE FUNDAMENTAL PARADOXES OF MODERN WARFARE IN AL MAQALEH V. GATES Ashley C. Nikkel* See how few of the cases of the suspension of the habeas corpus law, have been worthy of that suspension. They have been either real treason, wherein the parties might as well have been charged at once, or sham plots, where it was shameful they should ever have been suspected. Yet for the few cases wherein the suspension of the habeas corpus has done real good, that operation is now become habitual and the minds of the nation almost prepared to live under its constant suspension.1 INTRODUCTION On a cold December morning in 2002, United States military personnel entered a small wire cell at Bagram Airfield, in the Parwan province of Afghan- istan. There, they found Dilawar, a 20-year-old Afghan taxi driver, hanging naked and dead from the ceiling.2 The air force medical examiner who per- formed Dilawar’s autopsy reported his legs had been beaten so many times the tissue was “falling apart” and “had basically been pulpified.”3 The medical examiner ruled his death a homicide, the result of an interrogation lasting four days as Dilawar stood naked, his arms shackled over his head while U.S. inter- rogators performed the “common peroneal strike,” a debilitating blow to the side of the leg above the knee.4 The U.S. military detained Dilawar because he * J.D. Candidate, 2012, William S. Boyd School of Law, Las Vegas; B.A., 2009, University of Nevada, Reno. The Author would like to thank Professor Christopher L. -

Ethics Abandoned: Medical Professionalism and Detainee Abuse in the “War on Terror”

Ethics AbAndonEd: Medical Professionalism and Detainee Abuse in the “War on Terror” A task force report funded by IMAP/OSF November 2013 Copyright © 2013 Institute on Medicine as a Profession Table of Contents All rights reserved. this book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the AboUt iMAP And osF v publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. AcknoWlEdgMEnts vii Printed in the United states of America First Printing, 2013 ExEcUtivE sUMMArY xi institUtE on MEdicinE As A ProFEssion Findings And rEcoMMEndAtions xxxi columbia University, college of Physicians and surgeons 630 West 168th street P&s box 11, new York, nY 10032 introdUction 1 www.imapny.org chAPtEr 1: The role of health professionals in abuse of 11 prisoners in U.S. custody chAPtEr 2: Organizational structures and policies that 55 directed the role of health professionals in detainee abuse chAPtEr 3: Hunger strikes and force-feeding 83 chAPtEr 4: Education and training of military physicians on 121 treatment of prisoners chAPtEr 5: Health professional accountability for acts of 135 torture through state licensing and discipline tAsk ForcE MEMbEr biogrAPhiEs 157 APPEndicEs 1. Istanbul Protocol Guidelines for Medical Evaluations of 169 Torture and Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment, Annex 4 2. World Medical Association Declaration of Malta on Hunger Strikes 175 3. Ethics Statements and Opinions of Professional Associations on 181 Interrogation and Torture 4. Professional Misconduct Complaints Filed 201 notEs 215 About IMAP and OSF Funding for this report was provided by: thE institUtE on MEdicinE As A ProFEssion (iMAP) aims to make medical professionalism a field and a force. -

1 Extract from the IHF Report Human Rights in the OSCE Region: Europe, Central Asia and North America, Report 2005 (Events of 2

HONORARY CHAIRMAN ADVISORY BOARD (CHAIR) PRESIDENT Yuri Orlov Karl von Schwarzenberg Ulrich Fischer EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE VICE PRESIDENT Aaron Rhodes Holly Cartner Srdjan Dizdarevic Bjørn Engesland DEPUTY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Krassimir Kanev TREASURER Brigitte Dufour Stein-Ivar Aarsæther Vasilika Hysi Ferenc Köszeg Wickenburggasse 14/7, A-1080 Vienna, Austria; Tel +43-1-408 88 22; Fax 408 88 22-50 e-mail: [email protected] – internet: http://www.ihf-hr.org Bank account: Bank Austria Creditanstalt 0221-00283/00, BLZ 12 000 Extract from the IHF report Human Rights in the OSCE Region: Europe, Central Asia and North America, Report 2005 (Events of 2004) United States IHF FOCUS: rule of law; torture, ill-treatment and police misconduct; conditions in prisons; right to life; migrants, asylum seekers and refugees; rights of homosexuals. The United States’ (US) reputation as an advocate of human rights and democracy continued to be seriously damaged by its own human rights record in 2004. Coercive interrogation tactics that frequently amounted to inhuman and degrading treatment and even torture of detainees were common practice in places of detention outside the US but under US military control, such as Guantánamo Bay, Afghanistan, and Iraq. In addition, a number of actions and practices that undermine international law and human rights standards have became prevalent in the US government’s “war on terror.” In 2004, they included the indefinite detention of terrorist suspects who were neither charged of a crime nor brought before a court, the practice of holding suspects in “undisclosed locations,” and transferring them to states known for torturing detainees, among other examples. -

Glosario De Términos

Glosario de términos CJTF-7 Fuerza Conjunta Combinada-7 de EE.UU., Irak CITF Equipo de Trabajo de Investigación Penal DoD Departamento de Defensa de EE.UU. Informe DoD IG Despacho del inspector general del Departamento de Defensa, Informe No. 06-INTEL-10, Repaso de las investigaciones del maltrato de detenidos bajo la dirección del Departamento de Defensa, 25 de agosto de 2006 FBI Buró Federal de Investigación de EE.UU. ISG Grupo de Análisis de Irak JTF-GTMO Fuerza Conjunta de Guantánamo SASC Comisión sobre las Fuerzas Armadas en el Senado de EE.UU. Informe SASC Comisión sobre las Fuerzas Armadas en el Senado, Indagación sobre el trato de detenidos en custodia de Estados Unidos, 20 de noviembre de 2008 SERE Supervivencia, Evasión, Resistencia, Escape SMU TF Equipo de Trabajo de la Misión Especial de EE.UU., Irak SOUTHCOM Comando Sur de EE.UU., Departamento de Defensa I. Introducción El 27 de abril de 2009, se incoaron en este Juzgado diligencias previas acerca de “un plan autorizado y sistemático de tortura y malos tratos sobre personas privadas de libertad sin cargo alguno y sin los elementales derechos de todo detenido”, perpetrado por funcionarios no identificados del gobierno estadounidense contra personas detenidas en Guantánamo y en otras ubicaciones. En las diligencias se ha de indagar sobre las supuestas violaciones de los artículos 608, 609 y 611, junto con los artículos 607 bis y 173, del Código Penal, por “posibles perpetradores materiales e instigadores, colaboradores necesarios y cómplices del proceso". El 27 de enero de 2010, este Juzgado confirmó su jurisdicción sobre la investigación, aduciendo la reforma del artículo 23(4)-(5) de la Ley Orgánica del Poder Judicial (LOPJ).