Closing Gitmo Due to the Epiphany Approach to Habeas Corpus During the Military Commission Circus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government Turns the Other Way As Judges Make Findings About Torture and Other Abuse

USA SEE NO EVIL GOVERNMENT TURNS THE OTHER WAY AS JUDGES MAKE FINDINGS ABOUT TORTURE AND OTHER ABUSE Amnesty International Publications First published in February 2011 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2011 Index: AMR 51/005/2011 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.2 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 Judges point to human rights violations, executive turns away ........................................... 4 Absence -

Top Ten Taglines

Guantanamo: Detainee Accounts Table of Contents I. Transfer to Guantanamo.......................................................................................................... 1 II. Living conditions ..................................................................................................................... 5 III. Interrogation........................................................................................................................... 9 IV. Humilation and Degradation.............................................................................................. 13 V. Punishment............................................................................................................................. 15 VI. Beatings and other inappropriate use of force................................................................. 18 VII. Suicide Attempts................................................................................................................. 22 VIII. Release ................................................................................................................................ 22 IX. After-effects .......................................................................................................................... 23 Introduction The following is a compilation by Human Rights Watch of accounts by thirty-three former detainees at Guantanamo of their experiences there. Human Rights Watch interviewed sixteen of the detainees, reviewed press reports containing statements by former detainees interviewed -

Making Sense of Daesh in Afghanistan: a Social Movement Perspective

\ WORKING PAPER 6\ 2017 Making sense of Daesh in Afghanistan: A social movement perspective Katja Mielke \ BICC Nick Miszak \ TLO Joint publication by \ WORKING PAPER 6 \ 2017 MAKING SENSE OF DAESH IN AFGHANISTAN: A SOCIAL MOVEMENT PERSPECTIVE \ K. MIELKE & N. MISZAK SUMMARY So-called Islamic State (IS or Daesh) in Iraq and Syria is widely interpreted as a terrorist phenomenon. The proclamation in late January 2015 of a Wilayat Kho- rasan, which includes Afghanistan and Pakistan, as an IS branch is commonly interpreted as a manifestation of Daesh's global ambition to erect an Islamic caliphate. Its expansion implies hierarchical order, command structures and financial flows as well as a transnational mobility of fighters, arms and recruits between Syria and Iraq, on the one hand, and Afghanistan–Pakistan, on the other. In this Working Paper, we take a (new) social movement perspective to investigate the processes and underlying dynamics of Daesh’s emergence in different parts of the country. By employing social movement concepts, such as opportunity structures, coalition-building, resource mobilization and framing, we disentangle the different types of resource mobilization and long-term conflicts that have merged into the phenomenon of Daesh in Afghanistan. In dialogue with other approaches to terrorism studies as well as peace, civil war and security studies, our analysis focuses on relations and interactions among various actors in the Afghan-Pakistan region and their translocal networks. The insight builds on a ten-month fieldwork-based research project conducted in four regions—east, west, north-east and north Afghanistan—during 2016. We find that Daesh in Afghanistan is a context-specific phenomenon that manifests differently in the various regions across the country and is embedded in a long- term transformation of the religious, cultural and political landscape in the cross-border region of Afghanistan–Pakistan. -

Interrogation, Detention, and Torture DEBORAH N

Finding Effective Constraints on Executive Power: Interrogation, Detention, and Torture DEBORAH N. PEARLSTEIN* INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................1255 I. EXECUTIVE POLICY AND PRACTICE: COERCIVE INTERROGATION AND T O RTU RE ....................................................................................................1257 A. Vague or Unlawful Guidance................................................................ 1259 B. Inaction .................................................................................................1268 C. Resources, Training, and a Plan........................................................... 1271 II. ExECuTrVE LIMITs: FINDING CONSTRAINTS THAT WORK ...........................1273 A. The ProfessionalM ilitary...................................................................... 1274 B. The Public Oversight Organizationsof Civil Society ............................1279 C. Activist Federal Courts .........................................................................1288 CONCLUSION ........................................................................................................1295 INTRODUCTION While the courts continue to debate the limits of inherent executive power under the Federal Constitution, the past several years have taught us important lessons about how and to what extent constitutional and sub-constitutional constraints may effectively check the broadest assertions of executive power. Following the publication -

The Ethics of Intelligence Collection Ross W. Bellaby

What’s the Harm? The Ethics of Intelligence Collection Ross W. Bellaby Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of International Politics Aberystwyth University June 13th, 2011 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed ...................................................................... (Ross W. Bellaby) Date ........................................................................ STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where *correction services have been used, the extent and nature of the correction is clearly marked in a footnote(s). Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed ..................................................................... (Ross W. Bellaby) Date ........................................................................ [*this refers to the extent to which the text has been corrected by others] STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ..................................................................... (Ross W. Bellaby) Date ........................................................................ I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying -

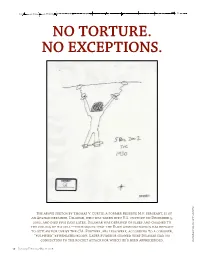

No Torture. No Exceptions

NO TORTURE. NO EXCEPTIONS. The above sketch by Thomas V. Curtis, a former Reserve M.P. sergeant, is of New York Times an Afghan detainee, Dilawar, who was taken into U.S. custody on December 5, 2002, and died five days later. Dilawar was deprived of sleep and chained to the ceiling of his cell—techniques that the Bush administration has refused to outlaw for use by the CIA. Further, his legs were, according to a coroner, “pulpified” by repeated blows. Later evidence showed that Dilawar had no connection to the rocket attack for which he’d been apprehended. A sketch by Thomas Curtis, V. a Reserve M.P./The 16 January/February/March 2008 Introduction n most issues of the Washington Monthly, we favor ar- long-term psychological effects also haunt patients—panic ticles that we hope will launch a debate. In this issue attacks, depression, and symptoms of post-traumatic-stress Iwe seek to end one. The unifying message of the ar- disorder. It has long been prosecuted as a crime of war. In our ticles that follow is, simply, Stop. In the wake of Septem- view, it still should be. ber 11, the United States became a nation that practiced Ideally, the election in November would put an end to torture. Astonishingly—despite the repudiation of tor- this debate, but we fear it won’t. John McCain, who for so ture by experts and the revelations of Guantanamo and long was one of the leading Republican opponents of the Abu Ghraib—we remain one. As we go to press, President White House’s policy on torture, voted in February against George W. -

“New Norms” and the Continuing Relevance of IHL in the Post-9/11

International Review of the Red Cross (2015), 97 (900), 1277–1293. The evolution of warfare doi:10.1017/S1816383116000138 The danger of “new norms” and the continuing relevance of IHL in the post-9/11 era Anna Di Lellio and Emanuele Castano Anna Di Lellio is a Professor of International Affairs at the New School of Public Engagement and New York University. Emanuele Castano is a Professor of Psychology at the New School for Social Research. Abstract In the post-9/11 era, the label “asymmetric wars” has often been used to question the relevance of certain aspects of international humanitarian law (IHL); to push for redefining the combatant/civilian distinction; and to try to reverse accepted norms such as the bans on torture and assassination. In this piece, we focused on legal and policy discussions in the United States and Israel because they better illustrate the dynamics of State-led “norm entrepreneurship”, or the attempt to propose opposing or modified norms as a revision of IHL. We argue that although these developments are to be taken seriously, they have not weakened the normative power of IHL or made it passé. On the contrary, they have made it more relevant than ever. IHL is not just a complex (and increasingly sophisticated) branch of law detached from reality. Rather, it is the embodiment of widely shared principles of morality and ethics, and stands as a normative “guardian” against processes of moral disengagement that make torture and the acceptance of civilian deaths more palatable. Keywords: IHL, asymmetric war, norm entrepreneurs, targeted killing, torture, terrorism, moral disengagement. -

Usa Amnesty International's Supplementary Briefing To

AI Index: AMR 51/061/2006 3 May 2006 USA AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL’S SUPPLEMENTARY BRIEFING TO THE UN COMMITTEE AGAINST TORTURE This briefing includes further information on the implementation by the United States of America (USA) of its obligations under the UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (Convention; UN Convention against Torture), with regard to the forthcoming consideration by the UN Committee Against Torture (the Committee) of the USA’s second periodic report.(1) The briefing updates Amnesty International’s concerns with regard to US "war on terror" detention, interrogation and related policies, as outlined in its preliminary briefing of August 2005, and provides additional information on domestic policies and practice. US OBLIGATIONS UNDER THE CONVENTION WITH RESPECT TO DETAINEES HELD IN THE CONTEXT OF THE "WAR ON TERROR" 1. General supplementary observations on definitions of torture and use of torture under interrogation, including deaths in custody (Articles 1 and 16) Evidence continues to emerge of widespread torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment of detainees held in US custody in Afghanistan, Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, Iraq and other locations. While the government continues to assert that abuses resulted for the most part from the actions of a few "aberrant" soldiers and lack of oversight, there is clear evidence that much of the ill-treatment has stemmed directly from officially santioned procedures and policies, including interrogation techniques approved by Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld for use in Guantánamo and later exported to Iraq.(2) While it seems that some practices, such as "waterboarding", were reserved for high value detainees, others appear to have been routinely applied during detentions and interrogations in Afghanistan, Guantánamo and Iraq. -

The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: an Empirical Study

© Reuters/HO Old – Detainees at XRay Camp in Guantanamo. The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empirical Study Benjamin Wittes and Zaahira Wyne with Erin Miller, Julia Pilcer, and Georgina Druce December 16, 2008 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 The Public Record about Guantánamo 4 Demographic Overview 6 Government Allegations 9 Detainee Statements 13 Conclusion 22 Note on Sources and Methods 23 About the Authors 28 Endnotes 29 Appendix I: Detainees at Guantánamo 46 Appendix II: Detainees Not at Guantánamo 66 Appendix III: Sample Habeas Records 89 Sample 1 90 Sample 2 93 Sample 3 96 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study EXECUTIVE SUMMARY he following report represents an effort both to document and to describe in as much detail as the public record will permit the current detainee population in American T military custody at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Station in Cuba. Since the military brought the first detainees to Guantánamo in January 2002, the Pentagon has consistently refused to comprehensively identify those it holds. While it has, at various times, released information about individuals who have been detained at Guantánamo, it has always maintained ambiguity about the population of the facility at any given moment, declining even to specify precisely the number of detainees held at the base. We have sought to identify the detainee population using a variety of records, mostly from habeas corpus litigation, and we have sorted the current population into subgroups using both the government’s allegations against detainees and detainee statements about their own affiliations and conduct. -

Accountability for Torture: Why a Criminal Investigation Is Necessary

Accountability for Torture: Why a Criminal Investigation is Necessary The Senate Intelligence Committee’s torture report confirms that the CIA tortured and brutalized prisoners in secret prisons around the world. The report, which is the culmination of a multi-year inquiry, also provides startling, new details about the level of cruelty perpetrated in our names. The conduct that the report describes violates both international and domestic law. Much of this conduct was authorized at the highest levels of government, with the involvement of the White House, the Justice Department, and the Defense Department. Given the gravity of the conduct described in the report, the Justice Department has a duty to investigate issues of criminal responsibility. A criminal investigation is an unequivocal obligation under international law. It is also necessary to repair our country’s damaged moral authority and prevent similar abuses from occurring again. The Justice Department Should Appoint a Special Prosecutor To ensure that the investigation of the torture program is comprehensive and insulated from political interference, Attorney General Eric Holder should appoint a special prosecutor from within the Justice Department and transfer to that special prosecutor all of his authority to investigate and prosecute crimes relating to the program. A special prosecutor would be able to make prosecutorial decisions without having to seek the attorney general’s permission. The special prosecutor’s mandate should be broad. It should include the authority to investigate and prosecute decisions to approve torture, to carry it out, and to conceal it. The special prosecutor should also examine CIA efforts to impede or improperly access the Senate’s investigation of CIA torture. -

China's Pervasive Use of Torture

CHINA’S PERVASIVE USE OF TORTURE HEARING BEFORE THE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 14, 2016 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 99–773 PDF WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 14:06 Jul 21, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\99773.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate CHRIS SMITH, New Jersey, Chairman MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Cochairman ROBERT PITTENGER, North Carolina TOM COTTON, Arkansas TRENT FRANKS, Arizona STEVE DAINES, Montana RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma DIANE BLACK, Tennessee BEN SASSE, Nebraska TIM WALZ, Minnesota DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon MICHAEL HONDA, California GARY PETERS, Michigan TED LIEU, California EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS CHRISTOPHER P. LU, Department of Labor SARAH SEWALL, Department of State STEFAN M. SELIG, Department of Commerce DANIEL R. RUSSEL, Department of State TOM MALINOWSKI, Department of State PAUL B. PROTIC, Staff Director ELYSE B. ANDERSON, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 14:06 Jul 21, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 U:\DOCS\99773.TXT DEIDRE CO N T E N T S STATEMENTS Page Opening Statement of Hon. -

Download Thepdf

Volume 59, Issue 5 Page 1395 Stanford Law Review KEEPING CONTROL OF TERRORISTS WITHOUT LOSING CONTROL OF CONSTITUTIONALISM Clive Walker © 2007 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University, from the Stanford Law Review at 59 STAN. L. REV. 1395 (2007). For information visit http://lawreview.stanford.edu. KEEPING CONTROL OF TERRORISTS WITHOUT LOSING CONTROL OF CONSTITUTIONALISM Clive Walker* INTRODUCTION: THE DYNAMICS OF COUNTER-TERRORISM POLICIES AND LAWS................................................................................................ 1395 I. CONTROL ORDERS ..................................................................................... 1403 A. Background to the Enactment of Control Orders............................... 1403 B. The Replacement System..................................................................... 1408 1. Control orders—outline................................................................ 1408 2. Control orders—contents and issuance........................................ 1411 3. Non-derogating control orders..................................................... 1416 4. Derogating control orders............................................................ 1424 5. Criminal prosecution.................................................................... 1429 6. Ancillary issues............................................................................. 1433 7. Review by Parliament and the Executive...................................... 1443 C. Judicial Review..................................................................................