Unit 13 Land Reforms and Other Developmental Measures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Active Agencies As on Jun 30, 2015 SR No Agency Name Address City State PIN STD Code Landline Mobile 1 P G Associates Room No. 5

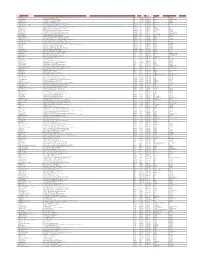

Active Agencies as on Jun 30, 2015 SR No Agency Name Address City State PIN STD Code Landline Mobile 1 P G Associates Room No. 5, First Floor, Ganesh Arcade, Near New Shah Market, Nehru Nagar, Agra, Agra Uttar Pradesh 282001 0562 3241045 NA 2 P C Associates 703-7Th Floor Maruti Plaza Sanjay Place Agra Agra Uttar Pradesh 282002 NA NA 9719344401 3 Kailash Associates S 13, Block No E 13/6, Raman Tower, Sanjay Place, Agra Agra Uttar Pradesh 202001 0562 3290521 9319072260/9319104191 4 Saraswat Associates Block No.11,Shop No.4,Shoes Market,Sanjay Place,Agra Agra Uttar Pradesh 282002 0562 4041762 9719544335 5 Shiv Associates Block S-8Shop No. 14 Shoe Marketsanjay Place Agra Agra Uttar Pradesh 282005 NA NA 09258318186 6 Sarbhoy Associates 7 Old Vijay Nagar Colony Agra 282004 Agra Uttar Pradesh 282004 0562 2852001/2852081 9719111717 7 Kaps Consultancy C/2/4 Shree Krishna Apartment Near Judges Bunglow Badakdev Ahmedabad Ahemdabad Gujarat 380054 NA NA 9909911983 8 Madhu Telecollection And Datacare 102, Samruddhi Complex, Opp.Sakar-Iii, Nr.C.U.Shah Colleage, Income Tax, Ahemdabad Gujarat 380009 079 40071404 NA 9 Shivam Agency 19,Devarchan Appartment Nr Bonny Travels Lane. Opp. Kochrab Ashram. Paladi Ahmedabadroom No-2 Ground Floor, Om Yashodhan Co-Operative Housing Societyltd Sahyog Mandir Road, Ram Maruti Road, Ghantali, Nuapada, Thane(W)-4000602 Ahemdabad Gujarat 380006 079 30613001 9988093065 10 K P Services A/310,Tirthraj Complex,Next To Hasubhai Chambers,Opp.Town Hall Elliesbridge Ahmedabad Ahemdabad Gujarat 380006 079 40091657 9824653344 11 -

A List of Terminated Vendors As on April 30, 2021. SR No ID Partner

A List of Terminated Vendors as on April 30, 2021. SR No ID Partner Name Address City Reason for Termination 1 124475 Excel Associates 123 Infocity Mall 1 Infocity Gandhinagar Sarkhej Highway , Gandhinagar Ahmedabad Breach Of Contract 2 125073 Karnavati Associates 303, Jeet Complex, Nr.Girish Cold Drink, Off.C.G.Road, Navrangpura Ahmedabad Breach Of Contract 3 132097 Sam Agency 29, 1St Floor, K B Commercial Center, Lal Darwaja, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, 380001 Ahmedabad Breach Of Contract 4 124284 Raza Enterprises Shopno 2 Hira Mohan Sankul Near Bus Stand Pimpalgaon Basvant Taluka Niphad District Nashik Ahmednagar Fraud Termination 5 124306 Shri Navdurga Services Millennium Tower Bldg No. A/5 Th Flra-201 Atharva Bldg Near S.T Stand Brahmin Ali, Alibag Dist Raigad 402201. Alibag Breach Of Contract 6 131095 Sharma Associates 655,Kot Atma Singh,B/S P.O. Hide Market, Amritsar Amritsar Breach Of Contract 7 124227 Aarambh Enterprises Shop.No 24, Jethliya Towars,Gulmandi, Aurangabad Aurangabad Fraud Termination 8 124231 Majestic Enterprises Shop .No.3, Khaled Tower,Kat Kat Gate, Aurangabad Aurangabad Fraud Termination 9 125094 Chudamani Multiservices Plot No.16, """"Vijayottam Niwas"" Aurangabad Breach Of Contract 10 NA Aditya Solutions No.2239/B,9Th Main, E Block, Rajajinagar, Bangalore, Karnataka -560010 Bangalore Fraud Termination 11 125608 Sgv Associates #90/3 Mask Road,Opp.Uco Bank,Frazer Town,Bangalore Bangalore Fraud Termination 12 130755 C.S Enterprises #31, 5Th A Cross, 3Rd Block, Nandini Layout, Bangalore Bangalore Breach Of Contract 13 NA Sanforce 3/3, 66Th Cross,5Th Block, Rajajinagar,Bangalore Bangalore Breach Of Contract 14 132890 Manasa Enterprises No-237, 2Nd Floor, 5Th Main First Stage, Khb Colony, Basaveshwara Nagar, Bangalore-560079 Bangalore Breach Of Contract 15 177367 Bharat Associates 243 Shivbihar Colony Near Arjun Ki Dairy Bankhana Bareilly Bareilly Breach Of Contract 16 132878 Nuton Smarte Service 102, Yogiraj Apt, 45/B,Nutan Bharat Society,Opp. -

1895 Jugatram Dave Was Born on 1St Septembe

MR. JUGATRAM DAVE Recipient of Jamnalal Bajaj Award for Constructive Work-1978 Born: 1895 Jugatram Dave was born on 1st September, 1895 at Laktar (Kathiawar). He studied upto Matric at Bombay and worked in a Gujarati monthly Vismi Sadi for some time. As the Bombay climate did not suit him, Swami Anand sent him to Baroda in 1915, where he worked as a teacher in a village school under the guidance of Acharya Kakasaheb Kalelkar for a couple of years. In 1917 he went to Ahmedabad to join the Kochrab Ashram and later shifted to the Sabarmati Ashram. He became an ideal ashramite, earning the confidence of Gandhiji and Kasturba. He worked first as a teacher in the national school established by Gandhiji and later joined the Navjivan Press. Jugatrambhai was deeply impressed by Gandhiji’s Constructive Programme and wished to take it up in right earnest on his own. This he could do only in 1924, when he went to stay at the Swaraj Ashram, Bardoli. He took an active part in flood relief operations in 1927 when many parts of Gujarat were devastated by floods and later in the Bardoli Satyagraha in 1928 under the leadership of Sardar Vallabbhai Patel. Soon afterwards he set up an ashram at Vedchhi, in the Raniparaj area inhabited mostly by Adivasis, as he felt that constructive work was most needed in uplifting the people of this socially and economically backward area. Jugatrambhai was, however, not able to give his undivided attention to organize and develop the Ashram activities on a wide and systematic scale till many years later. -

{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

Selfsame Spaces: Gandhi, Architecture and Allusions in Twentieth Century India. A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Venugopal Maddipati IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Catherine Asher, Adviser May, 2011 @ Venugopal Maddipati 2011 i Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following institutions and people for supporting my work. I am grateful to the American Institute of Indian Studies in Delhi, The Center of Science for Villages in Wardha and Kumarappapuram, The Indira Gandhi Institute of Developmental Research in Mumbai, The Gandhi Memorial Library in Delhi, The Center for Developmental Studies in Trivandrum, The Kutch Nav Nirman Abhiyaan and the University of Minnesota. I would like to thank the following individuals: Bindia Thapar, Purnima Mehta, Bindu Rajasenan, Soman Nair, Tilak Baker, Laurie Baker, Varsha Kaley, Vibha Gupta, Sameer Kuruve, David Faust, Donal Johnson, Eleanor Zelliot, Jane Blocker, Ajay Skaria, Anna Clark, Sarah Sik, Lynsi Spaulding, Riyaz Latif, Radha Dalal, Aditi Chandra, Sugata Ray, Atreyee Gupta, Midori Green, Sinem Arcak, Sherry, Dick, Jodi, Paul Wilson, Madhav Raman, Dhruv Sud, my parents, my sister Sushama, my mentors and my beloved Gurus, Frederick Asher and Catherine Asher. i Dedication Dedicated to my Tatagaru, Surapaneni Venugopal Rao. Tatagaru, if you can read this: You brought me up and taught me how to go beyond myself. ii Abstract In this dissertation, I suggest that the Indian political leader Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi infused deep and enigmatic meanings into everyday physical objects, particularly buildings. Indeed, the manner in which Gandhi named the buildings in his famous Satyagraha Ashram in Ahmedabad in the early part of the twentieth century, makes it somewhat difficult to write, in isolation, about their physical appearance. -

Ghoons Ko Ghoonsa Campaign

Drive against Bribe using RTI Act The Drive against Bribe using the Right to Information Act , organized by Mahiti Adhikar Gujarat Pahel at the Satyagrah Kochrab Ashram as part of a nation-wide campaign, comes to an end tomorrow, on July 15, 2006. This statement gives a synopsis of what has transpired so far and what is planned for the future. The Campaign That the campaign has been an unqualified success is shown by the following quantitative indicators 1. Number of visitors at the campaign site, Kochrab Ashram over 1400 2. Number of phone calls received 1275 calls 3. Number of applications under RTI filed 1366 The quantitative indicators tell only a limited story. The real impact has been through creation of awareness about the RTI Act amongst people at large ; empowerment and creation of confidence in common citizens that they can ask for information, and ask questions, from government functionaries; transformation of some of the citizens into active propagators of the RTI Act and its uses; and creation of a core of volunteers knowledgeable about the provisions, uses, intricacies of the RTI Act . As many as 300 volunteers have actively worked at the RTI camp at Kochrab Ashram during this fortnight. These volunteers have actually understood the RTI Act quite comprehensively and have also gained valuable experience in drafting applications under the RTI Act for a variety of problems and issues. Since the volunteers came from different parts of the state, their fanning out across the state and continuing to work for effective implementation of the RTI Act is likely to go a long way in a common people of the state using the RTI Act to solve their day to day problems instead of having to pay bribes. -

Embassy of India ASTANA NEWSLETTER

Embassy of India ASTANA NEWSLETTER Volume 1, Issue 17 October 16, 2015 German Chancellor Visits India Embassy of India Dr. Angela Merkel, Chancellor of Germany visited India from October 4-6, 2015 for 3rd Inter-Governmental Consultations ASTANA (IGC). She led a large delegation comprising several cabinet mem- bers and high profile business leaders. Inside this issue: Welcoming Dr. Merkel, President of India Shri Pranab Mukherjee said that India attaches high importance to its strate- German Chancellor visits 1-2 gic partnership with Germany. He said that relations between the India two countries are founded on common principles of democracy, rule of law and tolerance. He emphasized that India and Germany Chancellor Calls on President President of India visits 2-3 Jordan should work for closer integration of their economies and greater political understanding. The German Chancellor warmly reciprocat- President of India visits 3 ed President‟s sentiments and said that Germany shares common Palestine values with India. She stated that the world economy remains President of India visits 4 fragile and the two countries need to work together to stabilize it. Israel The third IGC meeting was held on 5th October where ACMA Buyer-Seller Meet 4 Prime Minister Modi and Chancellor Merkel agreed to steer the Celebration of Birth Anni- 5-6 strategic partnership between India and Germany into a new phase versary of Mahatma Gandhi by building on growing convergence on foreign and security issues and International Day of and the complementarities between the two economies. The two Non-violence leaders shared their common concern about the growing threat and reach of terrorism and extremism and underscored their readiness PM meets Chancellor NCC Delegation visits Ka- 6 to build closer collaboration to counter these challenges. -

Monograph on Kasturba

ININ SEARCH SEARCH OF OF KASTURBA KASTURBA AN AUTO/BIOGRAPHICAL READING OF OF THE MAHATMA AND HIS WIFE A MONOGRAPH __________________________________________________ LAVANYA VARADRAJAN (RESEARCH ASSOCIATE) UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. MALA PANDURANG (IN-CHARGE, GANDHIAN STUDIES CENTRE) UGC RECOGNISED GANDHIAN STUDIES CENTRE SEVA MANDAL EDUCATION SOCIETY’S DR. BHANUBHEN MAHENDRA NANAVATI COLLEGE OF HOME SCIENCE MATUNGA, MUMBAI 2017 Cover Designed By Mr Shravan Kamble, Faculty, Dept. Of Applied Arts, SCNI Polytechnic Printed By Mahavir Printers, Mumbai 400075 Published By Seva Mandal Education Society’s DR. BHANUBHEN MAHENDRA NANAVATI COLLEGE OF HOME SCIENCE (NAAC Reaccredited Grade “A” CGPA 3.64/4) UGC STATUS: COLLEGE WITH POTENTIAL FOR EXCELLENCE (CPE) MAHARSHI DHONDO KESHAV KARVE BEST COLLEGE AWARDEE SMT PARAMESHWARI GORANDHAS GARODIA EDUCATION COMPLEX, 338, R.A. KIDWAI ROAD. MATUNGA, MUMBAI 2017 ISBN 978-93-5258-741-2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincere gratitude to Dr Shilpa P Charankar, Principal & UGC recognised Gandhian Studies Centre, Dr. BMN College of Home Science, Matunga, for giving me the opportunity to pursue this study on Kasturba Gandhi. My deepest thanks to Prof. Mala Pandurang for her patient and painstaking guidance through the course of the research and writing of this project. A heartfelt hat-tip to Rajeshwar Thakore, whose passion for learning, and meticulous proof- reading skills, especially during the early drafts, helped this study immensely. This project would not have been possible without the literary resources available at the Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya Library and Mrs Vidya Subramanian, Librarian Dr. BMN College of Home Science. To both, my sincere thanks. CONTENTS Chapter I 1 Introduction: An Overview of the Framework of 1 the Study Chapter II 2 A Woman Imagined: Examining Kasturba’s 16 Presence/Absence in the Auto/Biographical Texts Chapter III 3 Public vs. -

Moved by Love the Memoirs of Vinoba Bhave

MOVED BY LOVE THE MEMOIRS OF VINOBA BHAVE (By Kalindi , Translated into English by Marjorie Sykes ) Preface This book is not Vinobaji's autobiography. He himself used to say that if he were to sit down and write, the result would not be 'the story of the self', I but a story of the 'not-self', because he was 'Vinoba the forgetful'. So he neither wrote nor dictated any such story of the not-self. But during the course of his thousands of talks he used to illustrate his topics by examples from experience, and these naturally included some incidents from his own life. This book is simply an attempt to pick out such incidents from different places and string them together. It follows that there are limits to what can be done. This is not a complete life story, only a glimpse of it. There is no attempt to give a full picture of every event, every thought, every step of the way. It brings together only chose incidents and stories which are to be had in Vinoba's own words. Some important events may therefore not be found in it, and in some places it will seem incomplete,, because the principle followed is to use only Vinoba's own account. Nevertheless, in spite of these limitations the glimpses will be found to be complete in themselves. Children are fond of playing with a 'jigsaw puzzle', where a complete picture, painted on a wooden plank, has been cut up into small parts of many shapes and sizes; the aim is to fit them together into their proper places and so re-build the picture. -

THE GANDHI STORY in His Own Words

THE GANDHI STORY in his own words Condensed and Compiled by Mahendra Meghani From M. K. Gandhi’s two books An Autobiography and Satyagraha in South Africa LOK'MILAP TRUST TO Charles F. Andrews (1871-1940) The greatest interpreter of Gandhi to the whole Western world, beloved of both Gandhi and Tagore FtiMsfoi by Gopal Meghani Lok'Milap Trust 364001 India P.Q,Box 23 (Sardamagar), Bhavnagar r e-mail: lokmilaptxustZOOC (ft yahoo.com Phone: +9 1 278 2566 402, 2566 566 iMyrnt & Typeset by Apurva Ashar, Ahmcdabad, India Phone: +91 2717 215590 * Email: [email protected] Printed Riddhish Printers, Ahmed abad, India Phone; +91 79 2562 0239 Btjok-bmdmg Kumar Binders, Ahmedabad, India Phone: +91 79 2562 4964 Intemcitforkii edition March 2009; 5,000 copies Pages; 12+220+24 (photographs) = 256 R 50 [postage extra] $10 [including overseas airmail postage] Gandhi and Tagore: two faces of modern India. It was an Englishman who was the link between these two great representatives of modem India: the ascetic and the bard. Few felt their joint impact more sensitively than the saintly Englishman, C. F. Andrews. Let him estimate them whom he loved so well: completely “I have never in my whole life met anyone so under- satisfying the needs of friendship and intellectual standing and spiritual sympathy as Tagore. Side by side poet 1 have had the supreme with the friendship with the , His happiness of a friendship with Mahatma Gandhi. as character, in his own way, is as great and as creative religious that of Tagore. However, it has about it an air of that modem. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Name : Dr. Kamleshkumar P Patel Date of Birth : 01-05-1960 Contact : Department of Physical Education, Mahadev Desai Samajseva Mahavidyalaya, Gujarat Vidyapith, Ahmedabad-380014, Gujarat, India Current Position : Associate Professor, Department of Physical Education Email : [email protected] Academic Qualification Exam passed Board/ Subjects Year Division/Grade University Merit. D.P.Ed. Gujarat Exam. Bo Physical Education 1982 58.17 % (Secon ard d) M.P.E. Gujarat University Physical Education 1989 60.18 % (First) M.A. Gujarat Vidyapith History 1992 61.63 % (First) M.Phil. Gujarat Vidyapith Physical Education 1999 70.83 % (First) Ph.D. Gujarat Vidyapith Physical Education 2003 Awarded P.G. Diploma Gujarat Vidyapith Yoga 2012 67.60 % (First) in Yoga 1 Contribution to Teaching Courses taught Name of University / College Institution Duration M.A. M.D. Collage, Gujarat Vidyapith 22 years P.G.Diploma in Yoga M.D. Collage, Gujarat Vidyapith 12 years Three Month Certificate M.D. Collage, Gujarat Vidyapith 6 years Course in Yoga B.P.E. M.D. S.S. Collage, Gujarat Vidyapith Sadra 15 years B.P.Ed. M.D. S.S. Collage, Gujarat Vidyapith Sadra 15 years M.P.Ed. M.D. S.S. Collage, Gujarat Vidyapith Sadra 15 years Area of Specialization • Physical Education • Sports Psychology • Teaching Method • Sports Science & Health • Yoga Teaching Method Academic Program and Courses Evolved 1. M.A. (Sports Practical) From 1993 2. M.A. Community Life From 1993 3. Post Graduate Diploma in Yoga Education From 2005 4. Post Graduate Diploma in Yoga Education (Part Time) From 2013 5. Three Month Certificate Course in Yoga From 2010 6. -

Website Trade Marks Agent List -30-11-2020

LIST OF TRADE MARKS AGENTS as of 30/11/2020 Certificate Renewal Sr. No. Name Address Contact No. E-mail No. Valild Upto 1 A. Bala Subramaniam 4/141, Vinayakar Koil 9944742133 [email protected] 869 31-03-2022 Street,Pannimadai,Coimbatore-641017. 2 A. Karunanithi No.3/22a, South Street, Kattumailur & Post, 9865356827 [email protected] 1759 31-03-2021 Veppur Taluk, Cuddalore-606304, Tamil Nadu 3 A. Lakshminarayan 1st floor, No.7, 4th Cross Street Extn. AGS 9840590483 [email protected] 415 31-03-2022 Colony, Velachery, Chennai-600042. 4 A. Rengarajan No.1/1, Raman Street, Chitlapakkam, Chennaii- 9381011200 [email protected] 920 31-03-2022 600064. 5 A.V. Nathan A.V. Nathan Associates, 451, 2nd Cross, 3rd 9900139484 [email protected] 1 31-03-2022 Block, 3rd Stage Basaveshwara Nagar, Bangalore-560079, Karnataka 6 AafIya Wasim Mirza Modern Colony, Jail Road, Near Circuit House 9607739786 [email protected] 1207 31-03-2023 Camp, Amravati-444602. 7 Aakansha Pankaj Arora 1, Mittal Chambers, 228 Nariman 8669011865 [email protected] 1700 31-03-2025 Point,Mumbai-400021. 8 Aanal Jigar Pancholi 401, Ashram Avenue, B"H Hochrab Ashram, 9879199384 [email protected] 819 31-03-2022 Paldi, Ahmedabad-980007. 9 Aarti Kumari B-55, Street No.18, Chhattarpur Enclave, 9811624297 [email protected] 1796 31-03-2021 Phase II, New Delhi-110074. 10 Abbas Haiderali Motorwala A/201, Fakhri Manzil, Saifee Park, Church 9870527236 [email protected] 917 31-03-2022 Road, MA 11 Abhay Kumar G-43, Laxmi Nagar,New Delhi-110092. -

Ram Lal Anand College (University of Delhi)

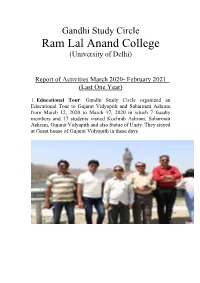

Gandhi Study Circle Ram Lal Anand College (University of Delhi) Report of Activities March 2020- February 2021 (Last One Year) 1. Educational Tour: Gandhi Study Circle organized an Educational Tour to Gujarat Vidyapith and Sabarmati Ashram from March 12, 2020 to March 17, 2020 in which 7 faculty members and 17 students visited Kochrab Ashram, Sabarmati Ashram, Gujarat Vidyapith and also Statue of Unity. They stayed at Guest house of Gujarat Vidyapith in these days. 2. Inter-College Essay Writing Competition: GSC conducted An online Essay Writing Competition on “ Relevance of Gandhian Cleanliness in Present World Scenario” on 7th April, 2020. Cash Prize and Merit Certificates were given to those students who secured 1st, 2nd, 3rd positions. More than 50 students participated in this competition through online mode. Circle provided E-certificates to all participants. 3. Five Day Lecture Series Webinar: Gandhi Study Circle organized A Five Day Lecture Series Webinar from 19th May to 23rd May 2020 through Google Meet platform. v Prof. Anamikshah, Vice Chancellor, Gujarat Vidyapith, Ahmedabad delivered his lecture on “आज क% ि'थ)त म, गाँधी th 2श4ा और समाज का अनबु ंध ” on 19 May 2020. v Dr Vedabhyas Kundu, program officer GSDS on “अहंसा?मक संवाद ” on 20th May 2020 v Dr. Rajender Khimani, Director, Gujarat Vidyapith on “महामारB म, गाँधी ” on 21st May. v Prof. Ramesh Bhardwaj, Director, Gandhi Bhawan, DU on “कोरोना के उFरकाल म, गांधी HिIट: एक समाधान ” on 22nd May. v Dr. Anula Maurya, Vice Chancellor, JRRSU, Jaipur on “महा?मा गाँधी क% HिIट म,-संयम” on 23rd May.