Gandhi's Laboratory: the South African

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Select Bibliography I I I I

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES: Books Gandhi M. K., Constructive Programme: Its Meaning and Place, I Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1941. Gandhi, M. K., An Autobiography or the Story of MJ Experiments with Truth, Ahmedabad, Navajivan Publishing HoJse, 1927. I I Gandhi, M. K., Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, Rev. ed. I Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1939. I Gandhi, M. K., Satyagraha in South Africa, Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1938. I Gandhi, M. K., Satyagraha Ashram Ka Itihas (In I Hindi), Translated from the Original in Gujarati by Ramna!rayan Chaudhuri, Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1948. ! I Gandhi, M. K., Collected Works OF MAHATJ11A GANDHI, THE I PUBLICATIONS DIVISION MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND I BROADCASTING GOVERNMENT OF INIDA\ 100 Vols. Delhi, 1958-1994. I I Gandhi, M. K., Delhi Diary, Prayer speeches from :10.9.47 to 30.1.48, Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1948. Gandhi, M. K., From Yeravda Mandir: Ashtam Observances, Translated from the original Gujarati by ValjJ Govindji Desai, 3rd ed. Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1945. ! ' I Gandhi, M. K., Gandhi's Health Guide, California, The Crossian Press, 2000. Gandhi, M. K., India's Case for Swaraj: Being Select Speeches, Writings, Interviews etc. of Mahatma Gandhi in England and India, September, 1931 to January 1932,!2nd ed., edited by Waman P. Kabodi, Bombay, Yeshanand, 1932. I Gandhi, M. K., Key to Health, Translated byi Sushila Nayyar, Ahmedabad, Vavajivan, 1948. I Gandhi, M. K., Mahatma Gandhi the essential writings Oxford World's Classics, J.; M. Brown, Oxford University PreJs, 2008. I I Gandhi, M. K., Non-violence in Peace and ;.var, Ahmedabad, Navajivan, 1942. Gandhi, M. K., Teaching of Mahatma Gandhi, Edited by Jag Parvesh Chander, Lahore, The Indian Printing Works, /1945. -

Active Agencies As on Jun 30, 2015 SR No Agency Name Address City State PIN STD Code Landline Mobile 1 P G Associates Room No. 5

Active Agencies as on Jun 30, 2015 SR No Agency Name Address City State PIN STD Code Landline Mobile 1 P G Associates Room No. 5, First Floor, Ganesh Arcade, Near New Shah Market, Nehru Nagar, Agra, Agra Uttar Pradesh 282001 0562 3241045 NA 2 P C Associates 703-7Th Floor Maruti Plaza Sanjay Place Agra Agra Uttar Pradesh 282002 NA NA 9719344401 3 Kailash Associates S 13, Block No E 13/6, Raman Tower, Sanjay Place, Agra Agra Uttar Pradesh 202001 0562 3290521 9319072260/9319104191 4 Saraswat Associates Block No.11,Shop No.4,Shoes Market,Sanjay Place,Agra Agra Uttar Pradesh 282002 0562 4041762 9719544335 5 Shiv Associates Block S-8Shop No. 14 Shoe Marketsanjay Place Agra Agra Uttar Pradesh 282005 NA NA 09258318186 6 Sarbhoy Associates 7 Old Vijay Nagar Colony Agra 282004 Agra Uttar Pradesh 282004 0562 2852001/2852081 9719111717 7 Kaps Consultancy C/2/4 Shree Krishna Apartment Near Judges Bunglow Badakdev Ahmedabad Ahemdabad Gujarat 380054 NA NA 9909911983 8 Madhu Telecollection And Datacare 102, Samruddhi Complex, Opp.Sakar-Iii, Nr.C.U.Shah Colleage, Income Tax, Ahemdabad Gujarat 380009 079 40071404 NA 9 Shivam Agency 19,Devarchan Appartment Nr Bonny Travels Lane. Opp. Kochrab Ashram. Paladi Ahmedabadroom No-2 Ground Floor, Om Yashodhan Co-Operative Housing Societyltd Sahyog Mandir Road, Ram Maruti Road, Ghantali, Nuapada, Thane(W)-4000602 Ahemdabad Gujarat 380006 079 30613001 9988093065 10 K P Services A/310,Tirthraj Complex,Next To Hasubhai Chambers,Opp.Town Hall Elliesbridge Ahmedabad Ahemdabad Gujarat 380006 079 40091657 9824653344 11 -

A List of Terminated Vendors As on April 30, 2021. SR No ID Partner

A List of Terminated Vendors as on April 30, 2021. SR No ID Partner Name Address City Reason for Termination 1 124475 Excel Associates 123 Infocity Mall 1 Infocity Gandhinagar Sarkhej Highway , Gandhinagar Ahmedabad Breach Of Contract 2 125073 Karnavati Associates 303, Jeet Complex, Nr.Girish Cold Drink, Off.C.G.Road, Navrangpura Ahmedabad Breach Of Contract 3 132097 Sam Agency 29, 1St Floor, K B Commercial Center, Lal Darwaja, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, 380001 Ahmedabad Breach Of Contract 4 124284 Raza Enterprises Shopno 2 Hira Mohan Sankul Near Bus Stand Pimpalgaon Basvant Taluka Niphad District Nashik Ahmednagar Fraud Termination 5 124306 Shri Navdurga Services Millennium Tower Bldg No. A/5 Th Flra-201 Atharva Bldg Near S.T Stand Brahmin Ali, Alibag Dist Raigad 402201. Alibag Breach Of Contract 6 131095 Sharma Associates 655,Kot Atma Singh,B/S P.O. Hide Market, Amritsar Amritsar Breach Of Contract 7 124227 Aarambh Enterprises Shop.No 24, Jethliya Towars,Gulmandi, Aurangabad Aurangabad Fraud Termination 8 124231 Majestic Enterprises Shop .No.3, Khaled Tower,Kat Kat Gate, Aurangabad Aurangabad Fraud Termination 9 125094 Chudamani Multiservices Plot No.16, """"Vijayottam Niwas"" Aurangabad Breach Of Contract 10 NA Aditya Solutions No.2239/B,9Th Main, E Block, Rajajinagar, Bangalore, Karnataka -560010 Bangalore Fraud Termination 11 125608 Sgv Associates #90/3 Mask Road,Opp.Uco Bank,Frazer Town,Bangalore Bangalore Fraud Termination 12 130755 C.S Enterprises #31, 5Th A Cross, 3Rd Block, Nandini Layout, Bangalore Bangalore Breach Of Contract 13 NA Sanforce 3/3, 66Th Cross,5Th Block, Rajajinagar,Bangalore Bangalore Breach Of Contract 14 132890 Manasa Enterprises No-237, 2Nd Floor, 5Th Main First Stage, Khb Colony, Basaveshwara Nagar, Bangalore-560079 Bangalore Breach Of Contract 15 177367 Bharat Associates 243 Shivbihar Colony Near Arjun Ki Dairy Bankhana Bareilly Bareilly Breach Of Contract 16 132878 Nuton Smarte Service 102, Yogiraj Apt, 45/B,Nutan Bharat Society,Opp. -

1895 Jugatram Dave Was Born on 1St Septembe

MR. JUGATRAM DAVE Recipient of Jamnalal Bajaj Award for Constructive Work-1978 Born: 1895 Jugatram Dave was born on 1st September, 1895 at Laktar (Kathiawar). He studied upto Matric at Bombay and worked in a Gujarati monthly Vismi Sadi for some time. As the Bombay climate did not suit him, Swami Anand sent him to Baroda in 1915, where he worked as a teacher in a village school under the guidance of Acharya Kakasaheb Kalelkar for a couple of years. In 1917 he went to Ahmedabad to join the Kochrab Ashram and later shifted to the Sabarmati Ashram. He became an ideal ashramite, earning the confidence of Gandhiji and Kasturba. He worked first as a teacher in the national school established by Gandhiji and later joined the Navjivan Press. Jugatrambhai was deeply impressed by Gandhiji’s Constructive Programme and wished to take it up in right earnest on his own. This he could do only in 1924, when he went to stay at the Swaraj Ashram, Bardoli. He took an active part in flood relief operations in 1927 when many parts of Gujarat were devastated by floods and later in the Bardoli Satyagraha in 1928 under the leadership of Sardar Vallabbhai Patel. Soon afterwards he set up an ashram at Vedchhi, in the Raniparaj area inhabited mostly by Adivasis, as he felt that constructive work was most needed in uplifting the people of this socially and economically backward area. Jugatrambhai was, however, not able to give his undivided attention to organize and develop the Ashram activities on a wide and systematic scale till many years later. -

{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

Selfsame Spaces: Gandhi, Architecture and Allusions in Twentieth Century India. A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Venugopal Maddipati IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Catherine Asher, Adviser May, 2011 @ Venugopal Maddipati 2011 i Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following institutions and people for supporting my work. I am grateful to the American Institute of Indian Studies in Delhi, The Center of Science for Villages in Wardha and Kumarappapuram, The Indira Gandhi Institute of Developmental Research in Mumbai, The Gandhi Memorial Library in Delhi, The Center for Developmental Studies in Trivandrum, The Kutch Nav Nirman Abhiyaan and the University of Minnesota. I would like to thank the following individuals: Bindia Thapar, Purnima Mehta, Bindu Rajasenan, Soman Nair, Tilak Baker, Laurie Baker, Varsha Kaley, Vibha Gupta, Sameer Kuruve, David Faust, Donal Johnson, Eleanor Zelliot, Jane Blocker, Ajay Skaria, Anna Clark, Sarah Sik, Lynsi Spaulding, Riyaz Latif, Radha Dalal, Aditi Chandra, Sugata Ray, Atreyee Gupta, Midori Green, Sinem Arcak, Sherry, Dick, Jodi, Paul Wilson, Madhav Raman, Dhruv Sud, my parents, my sister Sushama, my mentors and my beloved Gurus, Frederick Asher and Catherine Asher. i Dedication Dedicated to my Tatagaru, Surapaneni Venugopal Rao. Tatagaru, if you can read this: You brought me up and taught me how to go beyond myself. ii Abstract In this dissertation, I suggest that the Indian political leader Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi infused deep and enigmatic meanings into everyday physical objects, particularly buildings. Indeed, the manner in which Gandhi named the buildings in his famous Satyagraha Ashram in Ahmedabad in the early part of the twentieth century, makes it somewhat difficult to write, in isolation, about their physical appearance. -

Vijay Pratap

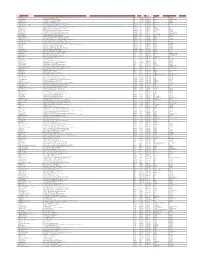

COMPILATION OF ARTICLES WRITTEN BY VIJAY PRATAP COMPILATION OF ARTICLES WRITTEN BY VIJAY PRATAP ENGLISH Printed on 13 December 2017 1 Printed on 13 December 2017 COMPILATION OF ARTICLES WRITTEN BY VIJAY PRATAP CONTENT LIST ARTICLES Page No. 1. Elections in India and their Impact on Weaker Sections 1-7 2 Danger of the Emergence of Inferiority Complex Pessimism 8-10 too 3 Changing Contours of Dalit Politics 11-14 4 Bahujan Wants Active Participation 15-17 5 Independent Dalit role not feasible in Bihar 18-20 6 The Context of the State Assembly Elections: Some Reflections 21-25 7 Lest We Lose the War 26-29 8 Excerpts from a letter to a friend on the future of Vasudhaiva 30-34 Kutumbakam 9 A Forum of Dialogues on Global Responsibility Towards 35-39 Democracy 10 The ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam’ Initiative 40-42 11 A Brief Note on “India - Central Asia Dialogue” 43-45 12 Notes on Voluntarism 46-48 13 Samvaad: A Personal of Journey of Discovering Dialogue as a 49-53 New Tool for Intervention 14 Victim, Perpetrator and Innocent Spectator: Introspecting 54-56 about Terrorism 15 Politics of Right to Information 57-60 2 Printed on 13 December 2017 COMPILATION OF ARTICLES WRITTEN BY VIJAY PRATAP 16 A Dialogue on Democracy 61-67 17 Poverty in India – An Overview 68-78 18 States and Democracy in South Asia 79-80 19 Ten Dialogues on "Policy Interventions for Consolidation of 81-82 Democracy" 20 Conversations on Democracy - Anil Bhattarai and Vijay 83-86 Pratap 21 Corruption and Communalism: Anti-Democratic Elements of 87-92 Indian Politics- Vijay Pratap 22 Towards North-South Solidarity : Some Challenges for 93-95 Building North-South Solidarity - Vijay Pratap 23 The Urgency of Dialogues on Democracy - Anil Bhattarai and 96-97 Vijay Pratap 24 Minorities and Democracy 98-99 25 Some Reflections on Funding and Voluntarism- Vijay Pratap; 100-103 Assisted by G. -

Ghoons Ko Ghoonsa Campaign

Drive against Bribe using RTI Act The Drive against Bribe using the Right to Information Act , organized by Mahiti Adhikar Gujarat Pahel at the Satyagrah Kochrab Ashram as part of a nation-wide campaign, comes to an end tomorrow, on July 15, 2006. This statement gives a synopsis of what has transpired so far and what is planned for the future. The Campaign That the campaign has been an unqualified success is shown by the following quantitative indicators 1. Number of visitors at the campaign site, Kochrab Ashram over 1400 2. Number of phone calls received 1275 calls 3. Number of applications under RTI filed 1366 The quantitative indicators tell only a limited story. The real impact has been through creation of awareness about the RTI Act amongst people at large ; empowerment and creation of confidence in common citizens that they can ask for information, and ask questions, from government functionaries; transformation of some of the citizens into active propagators of the RTI Act and its uses; and creation of a core of volunteers knowledgeable about the provisions, uses, intricacies of the RTI Act . As many as 300 volunteers have actively worked at the RTI camp at Kochrab Ashram during this fortnight. These volunteers have actually understood the RTI Act quite comprehensively and have also gained valuable experience in drafting applications under the RTI Act for a variety of problems and issues. Since the volunteers came from different parts of the state, their fanning out across the state and continuing to work for effective implementation of the RTI Act is likely to go a long way in a common people of the state using the RTI Act to solve their day to day problems instead of having to pay bribes. -

The Mountain Path Vol. 22 No. 4, Oct 1985

VOL. 22 No. IV OCTOBER 1985 THE MOUNTAIN PATH Editorial Board (A QUARTERLY) Sri K.K. Nambiar Mrs. Lucy Cornelssen "Arunachala! Thou dost root out the ego of those who meditate on Thee in the Smt. Shanta Rungachary heart. Oh Arunachala!" Dr. K. Subrahmaniam — The Marital Garland of Letters, verse 1 Sri A.R. Natarajan Vol. 22 OCTOBER 1985 No. 4 Publisher T.N. Venkataraman CONTENTS President, Board of Trustees, Page Sri Ramanasramam EDITORIAL: Ramana's Fate Tiruvannamalai — A.R. Natarajan ... 225 Two Decades of The Mountain Path . 228 Managing Editor Surrender V. Canesan — David Godman ... 231 A Guided Tour of Heaven II Letters and remittances should —• Douglas Harding . 235 be sent to : A Station Passed Through (Chapter II) The Managing Editor, — Arthur Osborne . 239 ''THE MOUNTAIN PATH", The Speciality of Ramana and His Teachings Sri Ramanasramam, P.O., — Prof. N.R. Krishnamoorthy Iyer . 241 Tiruvannamalai—606^603 S. India. Morality and Self Knowledge: in the light of the Life and the Teachings of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Annual Subscription — Michael lames . 242 How I Came to Bhagavan Sri Ramana INDIA Rs. 15 — Gobindram H. Daswani ... 250 FOREIGN £4.00 $8.00 Sri Bhagavan's Introduction to Vivekachudamani Life Subscription — Jr. by Sadhu Om and Michael lames . 252 Subramania Bharati: A God-Centred Poet Rs.150 £35.00 $70 — Dr. K. Subrahmanian . 259 Noble Ramana Single Copy — V. Ganesan . 261 Rs.4.00 £1.20 $2.50 Some Impressions of Sri Ramana Maharshi — Swami Ritajananda . 267 IA Precious Relic . 269 I'Turiya' — The Natural State Is it true Silence to rest — N.N. -

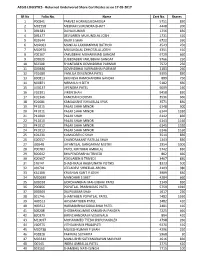

AEGIS LOGISTICS - Returned Undelivered Share Certificates As on 17-05-2017

AEGIS LOGISTICS - Returned Undelivered Share Certificates as on 17-05-2017 SR No Folio No. Name Cert No. Shares 1 P00841 PARVEZ HORMUSJI DAROGA 5751 830 2 M01558 MEENAXI SURENDRA BHATT 4448 200 3 D01681 DAYALKUMAR 1756 830 4 D01477 DEVILABEN MUKUNDLAL JOSHI 1731 410 5 R02644 RAJIV S SHAH 6722 260 6 M02063 MANILAL LAXMANBHAI RATHOD 4523 250 7 M00970 MUKUNDLAL CHHOTALAL JOSHI 4351 410 8 Y00107 YAKUBBHAI MUHAMMAD GANGAT 9729 660 9 Z00039 ZUBEDABEN YAKUBBHAI GANGAT 9766 250 10 S02308 SHANTABEN GOVINDBHAI PARMAR 7572 250 11 G00486 GOVINDBHAI VARWABHAI PARMAR 2183 260 12 V01680 VANLILA DEVENDRA PATEL 9395 830 13 B00813 BHUNESH RAMCHANDRA GANDHI 889 750 14 N00871 NIRMALA H SETH 5182 660 15 U00137 UPENDRA PATEL 9009 160 16 V02301 VIREN SHAH 9458 830 17 K01346 KANCHAN D DOSHI 3536 660 18 K01681 KAMALKANT ISHVARLAL VYAS 3571 830 19 P41015 PALAK SHAH MINOR 6148 900 20 P41011 PALAK SHAH MINOR 6144 1330 21 P41009 PALAK SHAH 6142 830 22 P41010 PALAK SHAH MINOR 6143 1160 23 P41012 PALAK SHAH MINOR 6145 1330 24 P41013 PALAK SHAH MINOR 6146 1160 25 K01230 KUMUDBEN C SHAH 3514 830 26 C00557 CHANDRAKANT RATILAL SHAH 1343 830 27 J00548 JAYANTILAL GANGARAM MISTRY 2954 1000 28 P00783 PATEL KIRITBHAI AMBALAL 5742 830 29 B00642 BHUPENDRABHAI TRIVEDI 862 660 30 K00967 KOKILABEN B TRIVEDI 3467 830 31 S10141 SHASHIKALA RAGHUNATH POTNIS 8323 500 32 L00702 LEELADEVI SHREELAL ARORA 4103 980 33 K61108 KRUSHAN KANT V JOSHI 3989 830 34 M00690 MANOHAR S SHET 4284 660 35 G00338 GORDHANBHAI MAHIJIBHAI PATEL 2149 830 36 P00866 POPATLAL PRABHUDAS PATEL 5759 1910 37 D00569 -

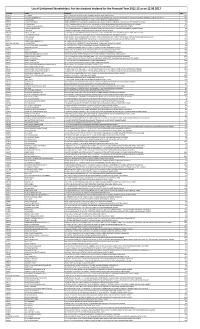

For the Dividend Declared for the Financial Year 2011-12 As on 12.09.2017

List of Unclaimed Shareholders: For the dividend declared for the Financial Year 2011-12 as on 12.09.2017 FOLIO NO NAME ADDRESS AMT A17671 A C SRAJAN 66 LUZ CHURCH ROAD MYLAPORE CHENNAI CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,600004 360 D00252 A DHAKSHINAMOORTHY PARTNER V M C TRADERS STOCKISTS OF A C LTD 6/10 MARIAMMAN KOIL RAMANATHAPURAM DT RAMANATHAPURAM RAMNAD,TAMIL NADU,623501 180 A02076 A JANARDHAN 8/1101 SESHAGIRINIVAS NEW ROAD COCHIN COCHIN ERNAKULAM,KERALA,682002 50 A02270 A K BHATTACHARYA UNITED COMMERCIAL BANK MATA ANANDA NAGAR SHIVALA HOSPITAL VARANASI U P VARANASI,UTTAR PRADESH,221001 50 A03705 A K NARAYANA C/O A K KESAUACHAR 451 TENTH CROSS GIRINAGAR SECOND PHASE BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,560085 50 P00351 A K RAMACHANDRAPRABHU 'PAVITRA' NO 949 24TH MAIN ROAD J P NAGAR II PHASE BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,560078 720 A17411 A KALPAKAM NARAYAN C/O V KAMESWARARAO 7-6-108 ENUGULAMALAL STREET SRIKAKULAM (A.P.) SRIKAKULAM,ANDHRA PRADESH,532001 36 A04366 A M DAVID 1 MISSION COMPOUND AJMER ROAD JAIPUR JAIPUR,RAJASTHAN,302006 50 M00394 A MURUGESAN 3 A D BLOCK V G RAO NAGAR EXTENSION KATPADI P O VELLORE N A A DT VELLORE NORTH ARCOT,TAMIL NADU,632007 46 A17672 A N VENKATALAKSHMI 361 XI A CROSS 29TH MAIN J P NAGAR I PHASE BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,560019 100 A04006 A NATARAJAN ACCOUNTANT THE NEDUNGADI BANK LN NORTH PARUR ERNAKULAM DIST NORTH PARUR NORTHPARUR ERNAKULAM,KERALA,683513 50 A17587 A P VASUDEV A 304, TEMPLE TREES APARTMENT JARAGANAHALLI KANAKAPURA ROAD BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,560078 200 A17757 A RADHA KRISHNAMURTHY 305 LAXMI BAI NAGAR NEW -

Embassy of India ASTANA NEWSLETTER

Embassy of India ASTANA NEWSLETTER Volume 1, Issue 17 October 16, 2015 German Chancellor Visits India Embassy of India Dr. Angela Merkel, Chancellor of Germany visited India from October 4-6, 2015 for 3rd Inter-Governmental Consultations ASTANA (IGC). She led a large delegation comprising several cabinet mem- bers and high profile business leaders. Inside this issue: Welcoming Dr. Merkel, President of India Shri Pranab Mukherjee said that India attaches high importance to its strate- German Chancellor visits 1-2 gic partnership with Germany. He said that relations between the India two countries are founded on common principles of democracy, rule of law and tolerance. He emphasized that India and Germany Chancellor Calls on President President of India visits 2-3 Jordan should work for closer integration of their economies and greater political understanding. The German Chancellor warmly reciprocat- President of India visits 3 ed President‟s sentiments and said that Germany shares common Palestine values with India. She stated that the world economy remains President of India visits 4 fragile and the two countries need to work together to stabilize it. Israel The third IGC meeting was held on 5th October where ACMA Buyer-Seller Meet 4 Prime Minister Modi and Chancellor Merkel agreed to steer the Celebration of Birth Anni- 5-6 strategic partnership between India and Germany into a new phase versary of Mahatma Gandhi by building on growing convergence on foreign and security issues and International Day of and the complementarities between the two economies. The two Non-violence leaders shared their common concern about the growing threat and reach of terrorism and extremism and underscored their readiness PM meets Chancellor NCC Delegation visits Ka- 6 to build closer collaboration to counter these challenges. -

Monograph on Kasturba

ININ SEARCH SEARCH OF OF KASTURBA KASTURBA AN AUTO/BIOGRAPHICAL READING OF OF THE MAHATMA AND HIS WIFE A MONOGRAPH __________________________________________________ LAVANYA VARADRAJAN (RESEARCH ASSOCIATE) UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. MALA PANDURANG (IN-CHARGE, GANDHIAN STUDIES CENTRE) UGC RECOGNISED GANDHIAN STUDIES CENTRE SEVA MANDAL EDUCATION SOCIETY’S DR. BHANUBHEN MAHENDRA NANAVATI COLLEGE OF HOME SCIENCE MATUNGA, MUMBAI 2017 Cover Designed By Mr Shravan Kamble, Faculty, Dept. Of Applied Arts, SCNI Polytechnic Printed By Mahavir Printers, Mumbai 400075 Published By Seva Mandal Education Society’s DR. BHANUBHEN MAHENDRA NANAVATI COLLEGE OF HOME SCIENCE (NAAC Reaccredited Grade “A” CGPA 3.64/4) UGC STATUS: COLLEGE WITH POTENTIAL FOR EXCELLENCE (CPE) MAHARSHI DHONDO KESHAV KARVE BEST COLLEGE AWARDEE SMT PARAMESHWARI GORANDHAS GARODIA EDUCATION COMPLEX, 338, R.A. KIDWAI ROAD. MATUNGA, MUMBAI 2017 ISBN 978-93-5258-741-2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincere gratitude to Dr Shilpa P Charankar, Principal & UGC recognised Gandhian Studies Centre, Dr. BMN College of Home Science, Matunga, for giving me the opportunity to pursue this study on Kasturba Gandhi. My deepest thanks to Prof. Mala Pandurang for her patient and painstaking guidance through the course of the research and writing of this project. A heartfelt hat-tip to Rajeshwar Thakore, whose passion for learning, and meticulous proof- reading skills, especially during the early drafts, helped this study immensely. This project would not have been possible without the literary resources available at the Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya Library and Mrs Vidya Subramanian, Librarian Dr. BMN College of Home Science. To both, my sincere thanks. CONTENTS Chapter I 1 Introduction: An Overview of the Framework of 1 the Study Chapter II 2 A Woman Imagined: Examining Kasturba’s 16 Presence/Absence in the Auto/Biographical Texts Chapter III 3 Public vs.