Monograph on Kasturba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discussion Questions for Gandhi

Discussion Questions for Gandhi Some of the major characters to watch for: Mohandas Gandhi (aka “Mahatma” or “Bapu”), Kasturba Gandhi (his wife), Charlie Andrews (clergyman), Mohammed Jinnah (leader of the Muslim faction), Pandit Nehru (leader of the Hindu faction—also called “Pandi-gi”), Sardar Patel (another Hindu leader), General Jan Smuts, General Reginald Dyer (the British commander who led the Massacre at Amritzar), Mirabehn (Miss Slade), Vince Walker (New York Times reporter) 1. Gandhi was a truly remarkable man and one of the most influential leaders of the 20th century. In fact, no less an intellect than Albert Einstein said about him: “Generations to come will scarce believe that such a one as this ever in flesh and blood walked upon this earth.” Why him, this small, unassuming man? What qualities caused tens of millions to follow him in his mission to liberate India from the British? 2. Consider Gandhi’s speech (about 30 minutes into the film) to the crowd regarding General Smuts’s new law (fingerprinting Indians, only Christian marriage will be considered valid, police can enter any home without warrant, etc.). The crowd is outraged and cries out for revenge and violence as a response to the British. This is a pivotal moment in Gandhi’s leadership. What does he do to get them to agree to a non-violent response? Why do they follow him? 3. Consider Gandhi’s response to the other injustices depicted in the film (e.g., his burning of the passes in South Africa that symbolize second-class citizenship, his request that the British leave the country after the Massacre at Amritzar, his call for a general strike—a “day of prayer and fasting”—in response to an unjust law, his refusal to pay bail after an unjust arrest, his fasts to compel the Indian people to change, his call to burn and boycott British-made clothing, his decision to produce salt in defiance of the British monopoly on salt manufacturing). -

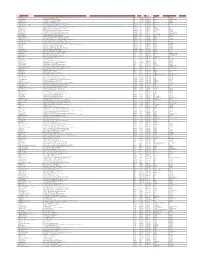

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Gandhi Warrior of Non-Violence P

SATYAGRAHA IN ACTION Indians who had spent nearly all their lives in South Africi Gandhi was able to get assistance for them from South India an appeal was made to the Supreme Court and the deportation system was ruled illegal. Meantime, the satyagraha movement continued, although more slowly as a result of government prosecution of the Indians and the animosity of white people to whom Indian merchants owed money. They demanded immediate payment of the entire sum due. The Indians could not, of course, meet their demands. Freed from jail once again in 1909, Gandhi decided that he must go to England to get more help for the Indians in Africa. He hoped to see English leaders and to place the problems before them, but the visit did little beyond acquainting those leaders with the difficulties Indians faced in Africa. In his nearly half year in Britain Gandhi himself, however, became a little more aware of India’s own position. On his way back to South Africa he wrote his first book. Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule. Written in Gujarati and later translated by himself into English, he wrote it on board the steamer Kildonan Castle. Instead of taking part in the usual shipboard life he used a packet of ship’s stationery and wrote the manuscript in less than ten days, writing with his left hand when his right tired. Hind Swaraj appeared in Indian Opinion in instalments first; the manuscript then was kept by a member of the family. Later, when its value was realized more clearly, it was reproduced in facsimile form. -

Gandhi's Impact on the Tamil Psyche

HINDUSTAN TIMES, NEW DELHI 10 hindustantimes THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2019 YEARS ON In the south 1869 - 2019 N O T E S FROM THE FIELD ' binary of Ambedkar/Periyar before I came Commemorative stamps starting with to Madurai. In the course of my doctoral the- India Post’s 2018 set, and those issued sis on Iyothee Dasa Pandithar [also spelt around the globe over the years Thass; he was a 19th and early 20th century Tamil Dalit social reformer who converted to Buddhism], I realised the contribution of Gandhi and Gandhians in changing Tamil society. Irrespective of what Dravidian par- ties would have you believe, without Gandhi there would have been little social justice or reform in Tamil Nadu that the state prides itself on,” says Stalin Rajangam, a Dalit scholar and researcher who teaches Tamil literature in Madurai’s American College. MADURAI’S GANDHI MEMORY The Gandhi Memorial Museum in Madurai is one of six national Gandhi monuments in India and the only one in south India. It is housed in a magnificent palace built in 1700 1 by the brave Madurai regent queen, Rani Mangammal. To add to the tourist attrac- tions, there is a giant model of the Tyranno- saurus Rex in the campus. The museum, inaugurated in 1959, is in custody of the bloodstained shawl and loincloth worn by Gandhi when he was shot by Nathuram Godse in 1948. It is kept in display in an alcove with walls painted in black. 2 However, there are other pieces of Gan- dhi’s legacy scattered in the south. -

Gandhi and Mani Bhavan

73 Gandhi and Mani Bhavan Sandhya Mehta Volume 1 : Issue 07, November 2020 1 : Issue 07, November Volume Independent Researcher, Social Media Coordinator of Mani Bhavan, Mumbai, [email protected] Sambhāṣaṇ 74 Abstract: This narrative attempts to give a brief description of Gandhiji’s association with Mani Bhavan from 1917 to 1934. Mani Bhavan was the nerve centre in the city of Bombay (now Mumbai) for Gandhiji’s activities and movements. It was from here that Gandhiji launched the first nationwide satyagraha of Rowlett Act, started Khilafat and Non-operation movements. Today it stands as a memorial to Gandhiji’s life and teachings. _______ The most distinguished address in a quiet locality of Gamdevi in Mumbai is the historic building, Mani Bhavan - the house where Gandhiji stayed whenever he was in Mumbai from 1917 to 1934. Mani Bhavan belonged to Gandhiji’s friend Revashankar Jhaveri who was a jeweller by profession and elder brother of Dr Pranjivandas Mehta - Gandhiji’s friend from his student days in England. Gandhiji and Revashankarbhai shared the ideology of non-violence, truth and satyagraha and this was the bond of their empathetic friendship. Gandhiji respected Revashankarbhai as his elder brother as a result the latter was ever too happy to Volume 1 : Issue 07, November 2020 1 : Issue 07, November Volume host him at his house. I will be mentioning Mumbai as Bombay in my text as the city was then known. Sambhāṣaṇ Sambhāṣaṇ Volume 1 : Issue 07, November 2020 75 Mani Bhavan was converted into a Gandhi museum in 1955. Dr Rajendra Prasad, then The President of India did the honours of inaugurating the museum. -

Sardar Patel's Role in Nagpur Flag Satyagraha

Sardar Patel’s Role in Nagpur Flag Satyagraha Dr. Archana R. Bansod Assistant Professor & Director I/c (Centre for Studies & Research on Life & Works of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel (CERLIP) Vallabh Vidya Nagar, Anand, Gujarat. Abstract. In March 1923, when the Congress Working Committee was to meet at Jabalpur, the Sardar Patel is one of the most foremost figures in the Municipality passed a resolution similar to the annals of the Indian national movement. Due to his earlier one-to hoist the national flag over the Town versatile personality he made many fold contribution to Hall. It was disallowed by the District Magistrate. the national causes during the struggle for freedom. The Not only did he prohibit the flying of the national great achievement of Vallabhbhai Patel is his successful flag, but also the holding of a public meeting in completion of various satyagraha movements, particularly the Satyagraha at Kheda which made him a front of the Town Hall. This provoked the th popular leader among the people and at Bardoli which launching of an agitation on March 18 . The earned him the coveted title of “Sardar” and him an idol National flag was hoisted by the Congress for subsequent movements and developments in the members of the Jabalpur Municipality. The District Indian National struggle. Magistrate ordered the flag to be pulled down. The police exhibited their overzealousness by trampling Flag Satyagraha was held at Nagput in 1923. It was the the national flag under their feet. The insult to the peaceful civil disobedience that focused on exercising the flag sparked off an agitation. -

Active Agencies As on Jun 30, 2015 SR No Agency Name Address City State PIN STD Code Landline Mobile 1 P G Associates Room No. 5

Active Agencies as on Jun 30, 2015 SR No Agency Name Address City State PIN STD Code Landline Mobile 1 P G Associates Room No. 5, First Floor, Ganesh Arcade, Near New Shah Market, Nehru Nagar, Agra, Agra Uttar Pradesh 282001 0562 3241045 NA 2 P C Associates 703-7Th Floor Maruti Plaza Sanjay Place Agra Agra Uttar Pradesh 282002 NA NA 9719344401 3 Kailash Associates S 13, Block No E 13/6, Raman Tower, Sanjay Place, Agra Agra Uttar Pradesh 202001 0562 3290521 9319072260/9319104191 4 Saraswat Associates Block No.11,Shop No.4,Shoes Market,Sanjay Place,Agra Agra Uttar Pradesh 282002 0562 4041762 9719544335 5 Shiv Associates Block S-8Shop No. 14 Shoe Marketsanjay Place Agra Agra Uttar Pradesh 282005 NA NA 09258318186 6 Sarbhoy Associates 7 Old Vijay Nagar Colony Agra 282004 Agra Uttar Pradesh 282004 0562 2852001/2852081 9719111717 7 Kaps Consultancy C/2/4 Shree Krishna Apartment Near Judges Bunglow Badakdev Ahmedabad Ahemdabad Gujarat 380054 NA NA 9909911983 8 Madhu Telecollection And Datacare 102, Samruddhi Complex, Opp.Sakar-Iii, Nr.C.U.Shah Colleage, Income Tax, Ahemdabad Gujarat 380009 079 40071404 NA 9 Shivam Agency 19,Devarchan Appartment Nr Bonny Travels Lane. Opp. Kochrab Ashram. Paladi Ahmedabadroom No-2 Ground Floor, Om Yashodhan Co-Operative Housing Societyltd Sahyog Mandir Road, Ram Maruti Road, Ghantali, Nuapada, Thane(W)-4000602 Ahemdabad Gujarat 380006 079 30613001 9988093065 10 K P Services A/310,Tirthraj Complex,Next To Hasubhai Chambers,Opp.Town Hall Elliesbridge Ahmedabad Ahemdabad Gujarat 380006 079 40091657 9824653344 11 -

Gandhi Sites in Durban Paul Tichmann 8 9 Gandhi Sites in Durban Gandhi Sites in Durban

local history museums gandhi sites in durban paul tichmann 8 9 gandhi sites in durban gandhi sites in durban introduction gandhi sites in durban The young London-trained barrister, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi 1. Dada Abdullah and Company set sail for Durban from Bombay on 19 April 1893 and arrived in (427 Dr Pixley kaSeme Street) Durban on Tuesday 23 May 1893. Gandhi spent some twenty years in South Africa, returning to India in 1914. The period he spent in South Africa has often been described as his political and spiritual Sheth Abdul Karim Adam Jhaveri, a partner of Dada Abdullah and apprenticeship. Indeed, it was within the context of South Africa’s Co., a firm in Porbandar, wrote to Gandhi’s brother, informing him political and social milieu that Gandhi developed his philosophy and that a branch of the firm in South Africa was involved in a court practice of Satyagraha. Between 1893 and 1903 Gandhi spent periods case with a claim for 40 000 pounds. He suggested that Gandhi of time staying and working in Durban. Even after he had moved to be sent there to assist in the case. Gandhi’s brother introduced the Transvaal, he kept contact with friends in Durban and with the him to Sheth Abdul Karim Jhaveri, who assured him that the job Indian community of the City in general. He also often returned to would not be a difficult one, that he would not be required for spend time at Phoenix Settlement, the communitarian settlement he more than a year and that the company would pay “a first class established in Inanda, just outside Durban. -

“In the Creator's Image: a Metabiographical Study of Two

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 18, Issue 4 (Nov. - Dec. 2013), PP 44-47 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org “In the Creator’s Image: A Metabiographical Study of Two Visual Biographies of Gandhi”. Preeti Kumar Abstract: A metabiographical analysis is concerned with the relational nature of biographical works and stresses how the temporal, geographical, intellectual and ideological location of the biographer constructs the biographical subject differently. The changing pictures of Gandhi in his manifold biographies raise questions as to how the subject’s identity is mediated to the readers and audience. Published in 2011, the Manga biography of Gandhi by Kazuki Ebine had as one of its primary sources the film Gandhi (1982) directed by Richard Attenborough. However, in spite of closely following the cinematic text, the Gandhi in Ebine’s graphic narrative is constructed differently from the protagonist of the source text. This paper analyses the narrative devices, the cinematic and comic vocabulary, the thematic concerns and the dominant discourses underlying the two visual biographies as exemplifying the cultural and ideological profile of the biographer. Key terms: Visual Biography, metabiography, Manga, Gandhi, ideology Biography, whether in books, theatre, television and film documentaries or the new media has become the dominant narrative mode of our time. The word „biography‟ literally means „life-writing‟ from the Medieval Greek: „bios‟ meaning „life‟ and „graphia‟ or „writing‟. The earliest definition of the term was offered by Dryden in his introduction to the Lives of Plutarch, in which he referred to “biography” as the “history of particular men‟s lives”. -

Chapter I Introduction

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Nonviolence is the pillar of Gandhi‘s life and work. His concept of nonviolence was based on cultivating a particular philosophical outlook and was integrally associated with truth. For him, nonviolence not just meant refraining from physical violence interpersonally and nationally but refraining from the inner violence of the heart as well. It meant the practice of active love towards one‘s oppressor and enemies in the pursuit of justice, truth and peace; ―Nonviolence cannot be preached‖ he insisted, ―It has to be practiced.‖ (Dear John, 2004). Non Violence is mightier than violence. Gandhi had studied very well the basic nature of man. To him, "Man as animal is violent, but in spirit he is non-violent.‖ The moment he awakes to the spirit within, he cannot remain violent". Thus, violence is artificial to him whereas non-violence has always an edge over violence. (Gandhi, M.K., 1935). Mahatma Gandhi‘s nonviolent struggle which helped in attaining independence is the biggest example. Ahimsa (nonviolence) has been part of Indian religious tradition for centuries. According to Mahatma Gandhi the concept of nonviolence has two dimensions i.e. nonviolence in action and nonviolence in thought. It is not a negative virtue rather it is positive state of love. The underlying principle of non- violence is "hate the sin, but not the sinner." Gandhi believes that man is a part of God, and the same divine spark resides in all men. Since the same spirit resides in all men, the possibility of reforming the meanest of men cannot be ruled out. -

A List of Terminated Vendors As on April 30, 2021. SR No ID Partner

A List of Terminated Vendors as on April 30, 2021. SR No ID Partner Name Address City Reason for Termination 1 124475 Excel Associates 123 Infocity Mall 1 Infocity Gandhinagar Sarkhej Highway , Gandhinagar Ahmedabad Breach Of Contract 2 125073 Karnavati Associates 303, Jeet Complex, Nr.Girish Cold Drink, Off.C.G.Road, Navrangpura Ahmedabad Breach Of Contract 3 132097 Sam Agency 29, 1St Floor, K B Commercial Center, Lal Darwaja, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, 380001 Ahmedabad Breach Of Contract 4 124284 Raza Enterprises Shopno 2 Hira Mohan Sankul Near Bus Stand Pimpalgaon Basvant Taluka Niphad District Nashik Ahmednagar Fraud Termination 5 124306 Shri Navdurga Services Millennium Tower Bldg No. A/5 Th Flra-201 Atharva Bldg Near S.T Stand Brahmin Ali, Alibag Dist Raigad 402201. Alibag Breach Of Contract 6 131095 Sharma Associates 655,Kot Atma Singh,B/S P.O. Hide Market, Amritsar Amritsar Breach Of Contract 7 124227 Aarambh Enterprises Shop.No 24, Jethliya Towars,Gulmandi, Aurangabad Aurangabad Fraud Termination 8 124231 Majestic Enterprises Shop .No.3, Khaled Tower,Kat Kat Gate, Aurangabad Aurangabad Fraud Termination 9 125094 Chudamani Multiservices Plot No.16, """"Vijayottam Niwas"" Aurangabad Breach Of Contract 10 NA Aditya Solutions No.2239/B,9Th Main, E Block, Rajajinagar, Bangalore, Karnataka -560010 Bangalore Fraud Termination 11 125608 Sgv Associates #90/3 Mask Road,Opp.Uco Bank,Frazer Town,Bangalore Bangalore Fraud Termination 12 130755 C.S Enterprises #31, 5Th A Cross, 3Rd Block, Nandini Layout, Bangalore Bangalore Breach Of Contract 13 NA Sanforce 3/3, 66Th Cross,5Th Block, Rajajinagar,Bangalore Bangalore Breach Of Contract 14 132890 Manasa Enterprises No-237, 2Nd Floor, 5Th Main First Stage, Khb Colony, Basaveshwara Nagar, Bangalore-560079 Bangalore Breach Of Contract 15 177367 Bharat Associates 243 Shivbihar Colony Near Arjun Ki Dairy Bankhana Bareilly Bareilly Breach Of Contract 16 132878 Nuton Smarte Service 102, Yogiraj Apt, 45/B,Nutan Bharat Society,Opp. -

1. Letter to Children of Bal Mandir

1. LETTER TO CHILDREN OF BAL MANDIR KARACHI, February 4, 1929 CHILDREN OF BAL MANDIR, The children of the Bal Mandir1are too mischievous. What kind of mischief was this that led to Hari breaking his arm? Shouldn’t there be some limit to playing pranks? Let each child give his or her reply. QUESTION TWO: Does any child still eat spices? Will those who eat them stop doing so? Those of you who have given up spices, do you feel tempted to eat them? If so, why do you feel that way? QUESTION THREE: Does any of you now make noise in the class or the kitchen? Remember that all of you have promised me that you will make no noise. In Karachi it is not so cold as they tried to frighten me by saying it would be. I am writing this letter at 4 o’clock. The post is cleared early. Reading by mistake four instead of three, I got up at three. I didn’t then feel inclined to sleep for one hour. As a result, I had one hour more for writing letters to the Udyoga Mandir2. How nice ! Blessings from BAPU From a photostat of the Gujarati: G.N. 9222 1 An infant school in the Sabarmati Ashram 2 Since the new constitution published on June 14, 1928 the Ashram was renamed Udyoga Mandir. VOL.45: 4 FEBRUARY, 1929 - 11 MAY, 1929 1 2. LETTER TO ASHRAM WOMEN KARACHI, February 4, 1929 SISTERS, I hope your classes are working regularly. I believe that no better arrangements could have been made than what has come about without any special planning.