THE GANDHI STORY in His Own Words

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Social Life of Khadi: Gandhi's Experiments with the Indian

The Social Life of Khadi: Gandhi’s Experiments with the Indian Economy, c. 1915-1965 by Leslie Hempson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Co-Chair Professor Mrinalini Sinha, Co-Chair Associate Professor William Glover Associate Professor Matthew Hull Leslie Hempson [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-5195-1605 © Leslie Hempson 2018 DEDICATION To my parents, whose love and support has accompanied me every step of the way ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF ACRONYMS v GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS vi ABSTRACT vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: THE AGRO-INDUSTRIAL DIVIDE 23 CHAPTER 2: ACCOUNTING FOR BUSINESS 53 CHAPTER 3: WRITING THE ECONOMY 89 CHAPTER 4: SPINNING EMPLOYMENT 130 CONCLUSION 179 APPENDIX: WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 183 BIBLIOGRAPHY 184 iii LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE 2.1 Advertisement for a list of businesses certified by AISA 59 3.1 A set of scales with coins used as weights 117 4.1 The ambar charkha in three-part form 146 4.2 Illustration from a KVIC album showing Mother India cradling the ambar 150 charkha 4.3 Illustration from a KVIC album showing giant hand cradling the ambar charkha 151 4.4 Illustration from a KVIC album showing the ambar charkha on a pedestal with 152 a modified version of the motto of the Indian republic on the front 4.5 Illustration from a KVIC album tracing the charkha to Mohenjo Daro 158 4.6 Illustration from a KVIC album tracing -

Active Agencies As on Jun 30, 2015 SR No Agency Name Address City State PIN STD Code Landline Mobile 1 P G Associates Room No. 5

Active Agencies as on Jun 30, 2015 SR No Agency Name Address City State PIN STD Code Landline Mobile 1 P G Associates Room No. 5, First Floor, Ganesh Arcade, Near New Shah Market, Nehru Nagar, Agra, Agra Uttar Pradesh 282001 0562 3241045 NA 2 P C Associates 703-7Th Floor Maruti Plaza Sanjay Place Agra Agra Uttar Pradesh 282002 NA NA 9719344401 3 Kailash Associates S 13, Block No E 13/6, Raman Tower, Sanjay Place, Agra Agra Uttar Pradesh 202001 0562 3290521 9319072260/9319104191 4 Saraswat Associates Block No.11,Shop No.4,Shoes Market,Sanjay Place,Agra Agra Uttar Pradesh 282002 0562 4041762 9719544335 5 Shiv Associates Block S-8Shop No. 14 Shoe Marketsanjay Place Agra Agra Uttar Pradesh 282005 NA NA 09258318186 6 Sarbhoy Associates 7 Old Vijay Nagar Colony Agra 282004 Agra Uttar Pradesh 282004 0562 2852001/2852081 9719111717 7 Kaps Consultancy C/2/4 Shree Krishna Apartment Near Judges Bunglow Badakdev Ahmedabad Ahemdabad Gujarat 380054 NA NA 9909911983 8 Madhu Telecollection And Datacare 102, Samruddhi Complex, Opp.Sakar-Iii, Nr.C.U.Shah Colleage, Income Tax, Ahemdabad Gujarat 380009 079 40071404 NA 9 Shivam Agency 19,Devarchan Appartment Nr Bonny Travels Lane. Opp. Kochrab Ashram. Paladi Ahmedabadroom No-2 Ground Floor, Om Yashodhan Co-Operative Housing Societyltd Sahyog Mandir Road, Ram Maruti Road, Ghantali, Nuapada, Thane(W)-4000602 Ahemdabad Gujarat 380006 079 30613001 9988093065 10 K P Services A/310,Tirthraj Complex,Next To Hasubhai Chambers,Opp.Town Hall Elliesbridge Ahmedabad Ahemdabad Gujarat 380006 079 40091657 9824653344 11 -

Gandhi Sites in Durban Paul Tichmann 8 9 Gandhi Sites in Durban Gandhi Sites in Durban

local history museums gandhi sites in durban paul tichmann 8 9 gandhi sites in durban gandhi sites in durban introduction gandhi sites in durban The young London-trained barrister, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi 1. Dada Abdullah and Company set sail for Durban from Bombay on 19 April 1893 and arrived in (427 Dr Pixley kaSeme Street) Durban on Tuesday 23 May 1893. Gandhi spent some twenty years in South Africa, returning to India in 1914. The period he spent in South Africa has often been described as his political and spiritual Sheth Abdul Karim Adam Jhaveri, a partner of Dada Abdullah and apprenticeship. Indeed, it was within the context of South Africa’s Co., a firm in Porbandar, wrote to Gandhi’s brother, informing him political and social milieu that Gandhi developed his philosophy and that a branch of the firm in South Africa was involved in a court practice of Satyagraha. Between 1893 and 1903 Gandhi spent periods case with a claim for 40 000 pounds. He suggested that Gandhi of time staying and working in Durban. Even after he had moved to be sent there to assist in the case. Gandhi’s brother introduced the Transvaal, he kept contact with friends in Durban and with the him to Sheth Abdul Karim Jhaveri, who assured him that the job Indian community of the City in general. He also often returned to would not be a difficult one, that he would not be required for spend time at Phoenix Settlement, the communitarian settlement he more than a year and that the company would pay “a first class established in Inanda, just outside Durban. -

Gandhi E Le Donne Occidentali

Gandhi e le donne occidentali Di Thomas Weber* Abstract: This paper is the Italian translation of an edited chapter of Thomas Weber’s Going Native. Gandhi’s Relationship With Western Women (Roli Books, New Delhi 2011) in which Gandhi’s attitudes to and relationships with women are analysed. Many Western women inspired him, worked with him, supported him in his political activities in South Africa and India, or contributed to shaping his international image. Of particular note are those women who “became native” to live with Gandhi as close friends and disciples. Through these fascinating women, we get a different insight into Gandhi’s life. *** Il rapporto di Gandhi con le donne si è rivelato di irresistibile fascino per molti. Molto spesso le persone che non conoscono praticamente nulla del Mahatma commentano il fatto che “dormì” con giovani donne durante la vecchiaia. Gran parte di questo deriva dall’interesse pruriginoso promosso da biografie sensazionalistiche o libri volti a smascherare il “mito del Mahatma” (Ved Metha 1976). Gandhi parlava spesso delle donne come del sesso più forte (e questo è stato visto come una forma di paternalismo dai critici, soprattutto di orientamento femminista) e di come desiderasse essere una madre per i suoi seguaci. Non sorprende pertanto che le collezioni delle sue lettere e dei suoi discorsi “sulle donne” siano molte. Ciò che meraviglia è quanto poco lavoro accademico sia stato intrapreso sul suo atteggiamento nei confronti e sulle sue relazioni con le donne. Nel 1953, Eleanor Morton pubblicò un libro intitolato The Women in Gandhi’s Life (Women Behind Mahatma Gandhi nell’edizione britannica dell’anno successivo). -

Friends of Gandhi

FRIENDS OF GANDHI Correspondence of Mahatma Gandhi with Esther Færing (Menon), Anne Marie Petersen and Ellen Hørup Edited by E.S. Reddy and Holger Terp Gandhi-Informations-Zentrum, Berlin The Danish Peace Academy, Copenhagen Copyright 2006 by Gandhi-Informations-Zentrum, Berlin, and The Danish Peace Academy, Copenhagen. Copyright for all Mahatma Gandhi texts: Navajivan Trust, Ahmedabad, India (with gratitude to Mr. Jitendra Desai). All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transacted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers. Gandhi-Informations-Zentrum: http://home.snafu.de/mkgandhi The Danish Peace Academy: http://www.fredsakademiet.dk Friends of Gandhi : Correspondence of Mahatma Gandhi with Esther Færing (Menon), Anne Marie Petersen and Ellen Hørup / Editors: E.S.Reddy and Holger Terp. Publishers: Gandhi-Informations-Zentrum, Berlin, and the Danish Peace Academy, Copenhagen. 1st edition, 1st printing, copyright 2006 Printed in India. - ISBN 87-91085-02-0 - ISSN 1600-9649 Fred I Danmark. Det Danske Fredsakademis Skriftserie Nr. 3 EAN number / strejkode 9788791085024 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ESTHER FAERING (MENON)1 Biographical note Correspondence with Gandhi2 Gandhi to Miss Faering, January 11, 1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, January 15, 1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, March 20, 1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, March 31,1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, April 15, 1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, -

A List of Terminated Vendors As on April 30, 2021. SR No ID Partner

A List of Terminated Vendors as on April 30, 2021. SR No ID Partner Name Address City Reason for Termination 1 124475 Excel Associates 123 Infocity Mall 1 Infocity Gandhinagar Sarkhej Highway , Gandhinagar Ahmedabad Breach Of Contract 2 125073 Karnavati Associates 303, Jeet Complex, Nr.Girish Cold Drink, Off.C.G.Road, Navrangpura Ahmedabad Breach Of Contract 3 132097 Sam Agency 29, 1St Floor, K B Commercial Center, Lal Darwaja, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, 380001 Ahmedabad Breach Of Contract 4 124284 Raza Enterprises Shopno 2 Hira Mohan Sankul Near Bus Stand Pimpalgaon Basvant Taluka Niphad District Nashik Ahmednagar Fraud Termination 5 124306 Shri Navdurga Services Millennium Tower Bldg No. A/5 Th Flra-201 Atharva Bldg Near S.T Stand Brahmin Ali, Alibag Dist Raigad 402201. Alibag Breach Of Contract 6 131095 Sharma Associates 655,Kot Atma Singh,B/S P.O. Hide Market, Amritsar Amritsar Breach Of Contract 7 124227 Aarambh Enterprises Shop.No 24, Jethliya Towars,Gulmandi, Aurangabad Aurangabad Fraud Termination 8 124231 Majestic Enterprises Shop .No.3, Khaled Tower,Kat Kat Gate, Aurangabad Aurangabad Fraud Termination 9 125094 Chudamani Multiservices Plot No.16, """"Vijayottam Niwas"" Aurangabad Breach Of Contract 10 NA Aditya Solutions No.2239/B,9Th Main, E Block, Rajajinagar, Bangalore, Karnataka -560010 Bangalore Fraud Termination 11 125608 Sgv Associates #90/3 Mask Road,Opp.Uco Bank,Frazer Town,Bangalore Bangalore Fraud Termination 12 130755 C.S Enterprises #31, 5Th A Cross, 3Rd Block, Nandini Layout, Bangalore Bangalore Breach Of Contract 13 NA Sanforce 3/3, 66Th Cross,5Th Block, Rajajinagar,Bangalore Bangalore Breach Of Contract 14 132890 Manasa Enterprises No-237, 2Nd Floor, 5Th Main First Stage, Khb Colony, Basaveshwara Nagar, Bangalore-560079 Bangalore Breach Of Contract 15 177367 Bharat Associates 243 Shivbihar Colony Near Arjun Ki Dairy Bankhana Bareilly Bareilly Breach Of Contract 16 132878 Nuton Smarte Service 102, Yogiraj Apt, 45/B,Nutan Bharat Society,Opp. -

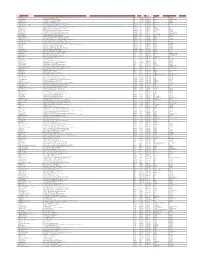

Unpaid / Unclaimed Dividend for Fy 2018-19 Flno Paycity

UNPAID / UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND FOR FY 2018-19 FLNO PAYCITY NAM1 NAMEEXT FHNAME ADD1 ADD2 ADD3 CITY PIN SHARESNETDVD NET MICRNOPROPIEPF 1203690000015751 A&N ISLANDS VENKATA RAMANA REDDY KOTTAPALLI 1-131 MACHAVARAM KANDUKURU PRAKASAM(DT) 0 100 800.00 800.00 47 29-OCT-2026 1202900000009985 Vadodara ASHOKBHAI RAMANBHAI PATEL AT & POST: RANOLI AT: RANOLI 0 150 1200.00 1200.00 48 29-OCT-2026 1201910100707978 VALSAD CHIMANBHAI BHAVANBHAI PATEL 1 TALAVCHORA TA CHIKHLII DI. VALSAD 0 100 800.00 800.00 50 29-OCT-2026 S0014666 NEW DELHI S KULWANT SINGH C/O ANAND FILLING STATION IRWIN ROAD NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110001 12 96.00 96.00 51 29-OCT-2026 K0011666 NEW DELHI KAMAL KISHORE RATHI 22 STOCK EXCHANGE BLDG ASAF ALI ROAD NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110001 76 608.00 608.00 52 29-OCT-2026 C0004874 NEW DELHI CITIBANK N A 124 JEEVAN BHARATHI BLDG CONNAUGHT CIRCUS NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110001 67 536.00 536.00 55 29-OCT-2026 R0006790 NEW DELHI RADHA KHANNA C/O PRITHVI RAJ KHANNA I S I CLUB CANTEEN MANAK BHAVAN 9 BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR MARG NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110002 74 592.00 592.00 57 29-OCT-2026 P0005340 NEW DELHI PRITHVI RAJ KHANNA ISI CLUB CANTEEN MANAK BHAVAN 9 BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR MARG NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110002 74 592.00 592.00 58 29-OCT-2026 A0008134 NEW DELHI ASUTOSH JOSHI C/O SHRI SUKH LAL JOSHI LINK HOUSE NAV BHARAT VANIJYA LTD 3 BAHADUR SHAH ZA NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110002 36 288.00 288.00 61 29-OCT-2026 N0007772 NEW DELHI NAVEEN SOOD 1815 IIND FLR UDAYCHAND MARG KATLA MUBARAKPUR NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110003 2 16.00 16.00 62 29-OCT-2026 N0009316 NEW DELHI NAMRITA MITTAL -

Gandhi Wields the Weapon of Moral Power (Three Case Stories)

Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power (Three Case Stories) By Gene Sharp Foreword by: Dr. Albert Einstein First Published: September 1960 Printed & Published by: Navajivan Publishing House Ahmedabad 380 014 (INDIA) Phone: 079 – 27540635 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.navajivantrust.org Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power FOREWORD By Dr. Albert Einstein This book reports facts and nothing but facts — facts which have all been published before. And yet it is a truly- important work destined to have a great educational effect. It is a history of India's peaceful- struggle for liberation under Gandhi's guidance. All that happened there came about in our time — under our very eyes. What makes the book into a most effective work of art is simply the choice and arrangement of the facts reported. It is the skill pf the born historian, in whose hands the various threads are held together and woven into a pattern from which a complete picture emerges. How is it that a young man is able to create such a mature work? The author gives us the explanation in an introduction: He considers it his bounden duty to serve a cause with all his ower and without flinching from any sacrifice, a cause v aich was clearly embodied in Gandhi's unique personality: to overcome, by means of the awakening of moral forces, the danger of self-destruction by which humanity is threatened through breath-taking technical developments. The threatening downfall is characterized by such terms as "depersonalization" regimentation “total war"; salvation by the words “personal responsibility together with non-violence and service to mankind in the spirit of Gandhi I believe the author to be perfectly right in his claim that each individual must come to a clear decision for himself in this important matter: There is no “middle ground ". -

Agrarian Movements in Bihar During the British Colonial Rule: a Case Study of Champaran Movement

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research ISSN: 2455-2070; Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 Received: 06-09-2020; Accepted: 17-09-2020; Published: 07-10-2020 www.socialsciencejournal.in Volume 6; Issue 5; 2020; Page No. 82-85 Agrarian movements in Bihar during the British colonial rule: A case study of Champaran movement Roma Rupam Department of History, Tilka Manjhi Bhagalpur University, Bhagalpur, Bihar, India Abstract British colonial rule in India brought about transformation in every area of Indian social, political and economic life. The impact of British colonial rule on agrarian society was decisive. The policy of colonial rule had changed the agrarian structure in India. The colonial rule had also developed new mechanisms to interact with peasants. Both new agrarian structure and new mechanisms to interact with peasants divided the agrarian society into the proprietors, working peasants and labourers. The roots of exploitation and misery of majority of people in agrarian society can be traced in the land tenure systems. The land relations were feudal in the permanent settlement areas. In the areas of Mahalwari and Ryotwari areas, the land had passed to absentee moneylenders, Sahukars and businessman due to large scale peasants’ indebtedness. This paper will give an overview of some of the major agrarian movements and their impact on the agrarian society. The peasants had been the worst sufferers of British Raj in colonial India. Because of the nature of land revenue system and its impact on agrarian society, the agrarian movements emerged in many parts of India. -

1895 Jugatram Dave Was Born on 1St Septembe

MR. JUGATRAM DAVE Recipient of Jamnalal Bajaj Award for Constructive Work-1978 Born: 1895 Jugatram Dave was born on 1st September, 1895 at Laktar (Kathiawar). He studied upto Matric at Bombay and worked in a Gujarati monthly Vismi Sadi for some time. As the Bombay climate did not suit him, Swami Anand sent him to Baroda in 1915, where he worked as a teacher in a village school under the guidance of Acharya Kakasaheb Kalelkar for a couple of years. In 1917 he went to Ahmedabad to join the Kochrab Ashram and later shifted to the Sabarmati Ashram. He became an ideal ashramite, earning the confidence of Gandhiji and Kasturba. He worked first as a teacher in the national school established by Gandhiji and later joined the Navjivan Press. Jugatrambhai was deeply impressed by Gandhiji’s Constructive Programme and wished to take it up in right earnest on his own. This he could do only in 1924, when he went to stay at the Swaraj Ashram, Bardoli. He took an active part in flood relief operations in 1927 when many parts of Gujarat were devastated by floods and later in the Bardoli Satyagraha in 1928 under the leadership of Sardar Vallabbhai Patel. Soon afterwards he set up an ashram at Vedchhi, in the Raniparaj area inhabited mostly by Adivasis, as he felt that constructive work was most needed in uplifting the people of this socially and economically backward area. Jugatrambhai was, however, not able to give his undivided attention to organize and develop the Ashram activities on a wide and systematic scale till many years later. -

GANDHIJI in SOUTH AFRICA Reminiscences of His Contemporaries

1 GANDHIJI IN SOUTH AFRICA Reminiscences of his Contemporaries Compiled by: E. S. Reddy [NOTE: This compilation consists of selected articles and short passages in books. For additional information, please see appendix.] 2 CONTENTS ANDREWS, C. F. “The Tribute of a Friend” (in Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, ed., Mahatma Gandhi: Essays and Reflections on His Life and Work. Fourth edition. Bombay: Jaico Publishing House, 1977. Originally published in 1939.) CATT, Mrs. Carie Chapman “Gandhi and South Africa” (in The Woman Citizen, March 1922) CURTIS, Lionel “Two meetings with Gandhi” (in Radhakrishnan, op. cit.) DESAI, Pragji “Satyagraha in South Africa” (in Chandrashanker Shukla, ed., Reminiscences of Gandhiji by Forty-eight Contributors. Bombay: Vora & Co., 1951.) GANDHI, Manilal “Memories of Gandhiji” (in Indian Review, Madras, March 1952) KRAUSE, F.E.T. “Gandhiji in South Africa” (in Shukla, op. cit.) LAWRENCE, Vincent “Sixty Years Memoir” (extract) MEHTA, P.J. “M.K. Gandhi and the South African Indian Problem” (in Indian Review, Madras, May 1911) PHILLIPS, Agnes M. “Recollections” (in Shukla, op. cit.) POLAK, H.S.L. “South African Reminiscences” (in Indian Review, Madras, February, March and May 1925) “A South African Reminiscence” (in Indian Review, October 1926) “Memories of Gandhi” (in Contemporary Review, London, March 1948) “Some South African Reminiscences” (in Chandrashanker Shukla, ed., Incidents of Gandhiji’s Life, by Fifty-four Contributors. Bombay: Vora & Co., 1949.) 3 POLAK, Mrs. Millie Graham “In the South African Days” (in Shukla, Incidents of Gandhiji’s Life.) “My South African Days with Gandhi” (in Indian Review, October 1964) POLAK, H.S.L. AND Mrs. Millie Graham “Gandhi, the Man” (in Indian Review, October 1929) SMUTS, J.C. -

1. Satyagraha in South Africa1

1. SATYAGRAHA IN SOUTH AFRICA1 FOREWORD Shri Valji Desai’s translation has been revised by me, and I can assure the reader that the spirit of the original in Gujarati has been very faithfuly kept by the translator. The original chapters were all written by me from memory. They were written partly in the Yeravda jail and partly outside after my premature release. As the translator knew of this fact, he made a diligent study of the file of Indian Opinion and wherever he discovered slips of memory, he has not hesitated to make the necessary corrections. The reader will share my pleasure that in no relevant or material paricular has there been any slip. I need hardly mention that those who are following the weekly chapters of My Experiments with Truth cannot afford to miss these chapters on satyagraha, if they would follow in all its detail the working out of the search after Truth. M. K. GANDHI SABARMATI 26th April, 19282 1 Gandhiji started writing in Gujarati the historty of Satyagraha in South Africa on November 26, 1923, when he was in the Yeravda Central Jail; vide “Jail Diary, 1923.” By the time he was released, on February 5, 1924, he had completed 30 chapters. The chapters of Dakshina Africana Satyagrahano Itihas, as it was entitled, appeared serially in the issues of the Navajivan, beginning on April 13, 1924, and ending on November 22, 1925. The preface to the first part was written at Juhu, Bombay, on April 2, 1924; that to the second appeared in Navajivan, 5-7-1925.