Agrarian Movements in Bihar During the British Colonial Rule: a Case Study of Champaran Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian History

Indian History Ancient History 1.Which of the following ancient Indian Kings had appointed Dhamma Mahamattas? [A] Asoka [B] Chandragupta Maurya [C] Kanishka [D] Chandragupta-II Correct Answer: A [Asoka] Notes: Dhamma Mahamattas were special officers appointed by Ashoka to spread the message of Dhamma or his Dharma. The Dhamma Mahamattas were required to look after the welfare of the people of different religions and to enforce the rules regarding the sanctity of animal life. 2.Who was the first Saka king in India? [A] Moga [B] Rudradaman [C] Azes [D] Ghatotkacha Correct Answer: A [ Moga ] Notes: An Indo-Scythian king, Moga (or Maues) was the first Saka king in India who established Saka power in Gandhara and extended supremacy over north-western India. 3.Who was ‘Kanthaka’ in the context of Gautam Buddha? [A] Charioteer [B] Body-guard [C] Cousin [D] Horse Correct Answer: D [ Horse ] Notes: Kanthaka was the royal horse of Gautama Buddha. 4.What symbol represents birth of Gautama Buddha? [A] Bodh tree [B] Lotus [C] Horse [D] Wheel Correct Answer: B [ Lotus ] Notes: Lotus and bull resembles the symbol of birth of Gautama Buddha. 5.What symbol represents nirvana of Gautama Buddha? [A] Lotus [B] Wheel [C] Horse [D] Bodhi Tree Correct Answer: D [ Bodhi Tree ] Notes: Bodhi Tree is the symbol of nirvana of Gautama Buddha. On the other hand, Stupa represents the symbol of death of Gautama Buddha. Further, The symbol ‘Horse’ signifies the renunciation of Buddha’s life. 6.During whose reign was the Fourth Buddhist Council held? [A] Ashoka [B] Kalasoka [C] Ajatsatru [D] Kanishka Correct Answer: D [ Kanishka ] Notes: The Fourth Buddhist Council was held at Kundalvana, Kashmir in 72 AD during the reign of Kushan king Kanishka. -

The Nehru Years in Indian Politics

Edinburgh Papers In South Asian Studies Number 16 (2001) ________________________________________________________________________ The Nehru Years in Indian Politics Suranjan Das Department of History University of Calcutta For further information about the Centre and its activities, please contact the Convenor Centre for South Asian Studies, School of Social & Political Studies, University of Edinburgh, 55 George Square, Edinburgh EH8 9LL. e-mail: [email protected] web page: www.ed.ac.uk/sas/ ISBN: 1 900 795 16 7 Paper Price: £2 inc. postage and packing 2 THE NEHRU YEARS IN INDIAN POLTICS: FROM A HISTORICAL HINDSIGHT Suranjan Das Professor, Department of History University of Calcutta and Director, Netaji Institute For Asian Studies, Calcutta The premise Not surprisingly, Jawaharlal Nehru’s years (1947-1964) as the first Prime Minister of the world’s largest democracy have attracted the attention of historians and other social scientists. Most of the works on Jawaharlal have, however, tended to be biographical in nature, and sympathetic in content. The best example of this trend is S. Gopal’s three-volume masterpiece. Amongst other historical biographies on Nehru, one should mention B.R. Nanda’s The Nehrus, R. Zakaria’s edited A Study of Nehru, Michael Brecher’s Nehru, a political biography, Norman Dorothy’s, Nehru: The First Sixty Years and Frank Moraes’ Jawaharlal Nehru: a biography. The latest in the biographical series comes from Judith Brown, and is simply entitled Nehru. Amongst the books celebrating Nehruvian ideals it also possible to include the earlier works of Rajni Kothari, particularly his Politics In India (1970) where he discussed the Congress system developed under Nehru. -

Gandhi Wields the Weapon of Moral Power (Three Case Stories)

Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power (Three Case Stories) By Gene Sharp Foreword by: Dr. Albert Einstein First Published: September 1960 Printed & Published by: Navajivan Publishing House Ahmedabad 380 014 (INDIA) Phone: 079 – 27540635 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.navajivantrust.org Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power FOREWORD By Dr. Albert Einstein This book reports facts and nothing but facts — facts which have all been published before. And yet it is a truly- important work destined to have a great educational effect. It is a history of India's peaceful- struggle for liberation under Gandhi's guidance. All that happened there came about in our time — under our very eyes. What makes the book into a most effective work of art is simply the choice and arrangement of the facts reported. It is the skill pf the born historian, in whose hands the various threads are held together and woven into a pattern from which a complete picture emerges. How is it that a young man is able to create such a mature work? The author gives us the explanation in an introduction: He considers it his bounden duty to serve a cause with all his ower and without flinching from any sacrifice, a cause v aich was clearly embodied in Gandhi's unique personality: to overcome, by means of the awakening of moral forces, the danger of self-destruction by which humanity is threatened through breath-taking technical developments. The threatening downfall is characterized by such terms as "depersonalization" regimentation “total war"; salvation by the words “personal responsibility together with non-violence and service to mankind in the spirit of Gandhi I believe the author to be perfectly right in his claim that each individual must come to a clear decision for himself in this important matter: There is no “middle ground ". -

Name : GYAN PRAKASH SHARMA Date of Birth: 26 June 1952

Name : GYAN PRAKASH SHARMA Date of Birth: 26 June 1952 Qualifications: MA (Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi) M Phil (Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi) PhD (Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi) Official Address: Department of History and Culture Faculty of Humanities and Languages Jamia Millia Islamia New Delhi 110025 Ph: 91(11) 26981717-2818(O) Mob: 9810873263 Current Address Official Address Dean Faculty of Humanities and Languages Jamia Millia Islamia Ph: 26983578, 26981717-2801,2802 Residential Address: 57, Uttaranchal Apartments 5, I.P. Extension Delhi 110092 Ph: 91(11) 22721502 e-mail address: [email protected] Specialisation : Modern Indian History (social and political history) Current Administrative Positions: 1. Dean, Faculty of Humanities and Languages, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi 2. Honorary Director, Munshi Premchand Archives and Literary Centre, Jamia Millia Islamia 3. Hony. Advisor, Centres of Higher Learning, Jamia Millia Islamia Administrative Positions Held Earlier: 1. Head, Department of History, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi (2007-2010) 2. Coordinator, Special Assistance Programme (SAP) UGC (2002-2007) 3. Coordinator, Transfer of Credits Programme Highlights of Important Contributions: Courses Framed: Communalism and the Right Wing Movements History of Municipal Institutions in India Health, Medicine and Society in Colonial India Agrarian Movements and Peasant Uprisings in Colonial India Research Projects Undertaken: Survey of Bonded Labour in North Bihar sponsored by the National Labour Institute, Government of India, 1975-76 Compilation of Village Notes of Patna District 1984-85 Any Other Innovative Activity: Involved course structuring of and preparation of study material on Indian National Movement for MA Classes of IGNOU Academic Engagements Since 2009 Lectures delivered: 1. -

To Study the Congress Policy Towards the Improvement of the Peasants

International Journal of Research in Economics and Social Sciences(IJRESS) Available online at: http://euroasiapub.org Vol. 7 Issue 11, November- 2017 ISSN(o): 2249-7382 | Impact Factor: 6.939| TO STUDY THE CONGRESS POLICY TOWARDS THE IMPROVEMENT OF THE PEASANTS Basudev Yadav Research Scholar Kalinga University Supervisor Name: Dr. Deepak Tomar Assistant Professor Department Of History ABSTRACTS Congress had to work in favour of peasants because they were compelled to work accordance to the manifesto of peasants programme passed in 1937 before elections and to consider the peasant’s problems two committees were formed.In this connection first committee had to enquire into the land rights and revenue; and was asked to advise on necessary amendments; while second committee was formed to look into the matters of rural indebtness.01And District Magistrates were asked not to take enhanced revenue; to avoid the hearings of the peasant disputes over taxes. In addition, an increasing number of U.P. congress representatives in the latter half of 1931. On the agrarian problem, begin to adopt a more combative and redical line than before. They spoke of the need for urgent action, especially in Oudh, to alleviate the distress of tenants. They were forced to abolish intermediaries between the farmers and the states. In 1934, a group of intellectuals founded the Congress Socialist Party (C.S.P.) to radicalise the Indian National Congress and were determined to initiate a process that would eventually lead to the development of a socialist society. Yet it never actually left Congress. INTRODUCTION They rightly believed that at that point especially when Jawahar Lal Nehru had emerged as the foremost radical within the Congress, the Indian National Congress was in a position to usher in a social revolution. -

Zamindari System & All India Kisan Sabha

UPSC Civil Services Examination Subject – UPSC GS-II Topic – Zamindari System & All India Kisan Sabha The Zamindari System in British India was a land revenue management system under the Permanent Settlement of Bengal. The settlement was between the landlords of Bengal known as zamindars and the British East India Company. The system recognised the zamindars as landowners who then let out their lands to tenant farmers in return of a share of the produce. The zamindar, in turn, had to pay a fixed sum to the British Government. This led to a lot of exploitation of the peasants. In this article, we will discuss the impact of the various groups opposed to the zamindari system on the freedom movement. It is an important topic for the History syllabus of UPSC prelims. Aspirants can check their preparation by subscribing to UPSC Prelims Test Series 2020 now!! To complement your preparation for the upcoming exam, check the following links: o UPSC Previous Year Question Papers o Current Affairs o UPSC Notes PDF o IAS Mock Tests o NCERT Notes PDF Zamindari System - Major Events Issues related to peasants were an important part of the freedom movement from the first decade of the twentieth century. One of the issues that the national movement focussed on after 1915 was the condition of the peasantry and their upliftment. As a result, the abolition of intermediaries and by extension the zamindari system increased in importance. Here are a few important events related to reforming the land revenue system during the early twentieth century: The first movement spearheaded by Mahatma Gandhi in India was related to peasants, which was the Champaran Satyagraha (1917) against forced indigo cultivation. -

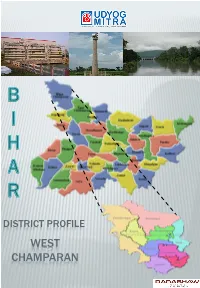

West Champaran Introduction

DISTRICT PROFILE WEST CHAMPARAN INTRODUCTION West Champaran is an administrative district in the state of Bihar. West Champaran district was carved out of old champaran district in the year 1972. It is part of Tirhut division. West Champaran is surrounded by hilly region of Nepal in the North, Gopalganj & part of East Champaran district in the south, in the east it is surrounded by East Champaran and in the west Padrauna & Deoria districts of Uttar Pradesh. The mother-tongue of this region is Bhojpuri. The district has its border with Nepal, it has an international importance. The international border is open at five blocks of the district, namely, Bagha- II, Ramnagar, Gaunaha, Mainatand & Sikta, extending from north- west corner to south–east covering a distance of 35 kms . HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The history of the district during the late medieval period and the British period is linked with the history of Bettiah Raj. The British Raj palace occupies a large area in the centre of the town. In 1910 at the request of Maharani, the palace was built after the plan of Graham's palace in Calcutta. The Court Of Wards is at present holding the property of Bettiah Raj. The rise of nationalism in Bettiah in early 20th century is intimately connected with indigo plantation. Raj Kumar Shukla, an ordinary raiyat and indigo cultivator of Champaran met Gandhiji and explained the plight of the cultivators and the atrocities of the planters on the raiyats. Gandhijii came to Champaran in 1917 and listened to the problems of the cultivators and the started the movement known as Champaran Satyagraha movement to end the oppression of the British indigo planters. -

University Grants Commission, New Delhi Recognized Journal No

University Grants Commission, New Delhi Recognized Journal No. 41311 ISSN: Print: 2347-5021 www.research-chronicler.com ISSN: Online: 2347-503X Addressing a Generation in Transition A Reading of Babu Brajakishore Prasad’s Presidential Address Bihar Students’ Conference, Chapra, 1911 Sunny Kumar Research Scholar, Department of History, B.R.A.B.U. Muzaffarpur, (Bihar) India Abstract The presidential address of Babu Brajkishore Prasad at the 1911 session of the sixth Bihar Students’ Conference—which took place annually during Dasahara1 period-- needs to be seen in its transitional, historical context. First of all, the speech takes place in 1911, when one of the most important missions of Babu Brajkishore Prasad’s public life and that of his other eminent contemporaries from Bihar, was about to become a reality. The mission, of course, was the carving out of Bihar from Bengal and making it a separate province. The issue of Bihar was settled with the Delhi Durbar proclamation in December 1911, cancelling the Partition of Bengal as announced in 1905. The separation of Bihar from Bengal was a great historical feat as it freed the Hindi-speaking areas of Bengal from one layer of colonial and cultural subjugation and allowed for them a socio-political identity and space in the newly emerging national consciousness under the one geographical, economic, social and cultural entity called Bihar, then written as Behar. Key Words : Generation, Transition, Province, Consensuses, Subjection However, the movement for the creation of Readers of Bryce’s American Bihar was not an easy task for its leaders. Commonwealth are no doubt aware that In fact, those espousing the cause of Bihar there exists in the United States a strong were seen to be moving in the opposite state patriotism, which subsists side by direction of the clarion call for national side with federal patriotism. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Dr. Awadhesh Kumar H.o.D & Assistant Professor Division of Economics & Agriculture Economics A N Sinha Institute of Social Studies, Patna Mobile : 98358 89013 e– mail : [email protected] Specialisation : (a) Rural Economics (b) Industrial Economics Experience : About 21 years’ Teaching and Research experience in different projects related to Social Issues and Rural Economics. Education & Training: ► Post Graduation in Economics from Patna University, Patna in 1997 Specialization in Rural Economics, Industrial Economics Grade – Second Class ► Qualified UGC – NET in June 1999 (Economics) ► PhD in Economics, B.R. Ambedkar Bihar University, Dec. 2019 Positions Held (in descending order) : (a) Assistant Professor, Division of Economics, A.N. Sinha Institute of Social Studies, Patna from August 2010 till date (11 years +) (b) Research Associate in Bihar Institute of Economic Studies, Patna from October 2003 to July 2010 (7 years+) (c) Lecturer (Ad-hoc) in Economics in B.N. College, Patna from October 2000 to September 2003 Skill : (a) Policy analysis for rural development, livelihood issues and tribal and SC / ST affairs (b) Collection, compilation and interpretation of statistical data Professional Experience and Achievement : ► August 2010 till date as Assistant Professor, Division of Economics, A.N. Sinha Institute of Social Studies, Patna (a) Member of national level seminars from time to time (b) Member of Purchase Committee (c) Coordinator of Support Programme for Urban Reforms in Bihar under DFID Publication 1. I have written an Article entitled, “Indian Agriculture in Economic Growth : An Evaluation” in the Indian Journal –The Hindustan Review, p.57-59, Vol. 32, No. 30, April- June 2008. -

Subaltern Resurgence

1 crisis states programme development research centre www Working Paper no.8 SUBALTERN RESURGENCE: A RECONNAISANCE OF PANCHAYAT ELECTION IN BIHAR Shaibal Gupta Asian Development Research Centre (ADRI) Patna, India January 2002 Copyright © Shaibal Gupta, 2002 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce any part of this Working Paper should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Programme, Development Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. Crisis States Programme Working papers series no.1 English version: Spanish version: ISSN 1740-5807 (print) ISSN 1740-5823 (print) ISSN 1740-5815 (on-line) ISSN 1740-5831 (on-line) 1 Crisis States Programme Subaltern Resurgence: A reconnaissance of Panchayat election in Bihar Shaibal Gupta Asian Development Research Institute (ADRI), Patna, India The decision of the British Council to wind up its cute library from Patna and surfacing of a new social composition, as revealed in the recently held Panchayat Election in Bihar, probably hold promise of a unique political, academic and cultural potboiler in the firmament of this state. If the British Council Library was the last citadel of Eurocentric world view, the social constellation which has emerged out of the Panchayat election, will be the final triumph of a Bihar-centric rural world view. The chasm between these two world views was being witnessed for a long time; but with the decision of the banishment of the library from this benighted state and further democratization and electoral empowerment through the recent Panchayat Election, there will now be a symbolic breach in the dialogue between these two world views. -

Political Perspectives to Chronic Poverty

Chronic Poverty and Social Conflict in Bihar N.R. Mohanty 1. Introduction Chronic poverty trends cannot be examined without considering the impact of various social conflicts afflicting a region. It is true that all forms of poverty cannot be explained by conflicts as much as all conflicts cannot be attributed to poverty. But, in many economically backward states, poverty and conflict have largely a two-way relationship; poverty is both a cause and consequence of conflict. There is a broad consensus on the definition of chronic poverty as severe deprivation of basic human needs over an extended period of time. But there is no unanimity as to what constitutes the basic needs. Over a period of time, the ‘basic needs’ has expanded to encompass not only food, water, shelter and clothing, but access to other assets such as education, health, participation in political process, security and dignity. Those who are chronically poor are poor in several ways and often suffer multi-dimensional poverty - food scarcity; lack of resources to send their children to school or provide health care for the sick (Hulme, Moore and Shepherd 2005). Conflict is a struggle, between individuals or collectivities over values or claims to status, power and scarce resources in which the aims of the conflicting parties are to assert their values or claims over those of others (Goodhand and Hulme 1999: 14). 1 2. The Poverty-Conflict Interface On the face of it, poverty and conflict are different phenomena that plague society, but in reality, there is a close relationship between the two. Those who dismiss the link between poverty and conflict generally argue that poverty may lead to conflict when other factors are present; it is not a sufficient condition. -

Aman Sir Wifistudy Use Code Liveaman on Unacademy

AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY(OFFICIAL) AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY USEUSE CODE CODE “AMAN LI11V”E ONAMAN UNACADEMY ON& GET UNACADEMY 10% DISCOUNT AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY(OFFICIAL) DAILY FREE SESSIONS AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY USEUSE CODE CODE “AMAN LI11V”E ONAMAN UNACADEMY ON& GET UNACADEMY 10% DISCOUNT AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY(OFFICIAL) AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY USEUSE CODE CODE “AMAN LI11V”E ONAMAN UNACADEMY ON& GET UNACADEMY 10% DISCOUNT AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY(OFFICIAL) AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY USELIVEAMANUSE CODE CODE “AMAN LI11V”E ONAMAN UNACADEMY ON& GET UNACADEMY 10% DISCOUNT AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY(OFFICIAL) Q1. With reference to the Indian freedom struggle, which one of the following is the correct chronological order of the given events? भारतीय वतंत्रता संग्राम के संदभभ मᴂ, नि륍िलिखित मᴂ से कौि सा घटिाओं के सही कािािुक्रलमक क्रम है? a) Partition of Bengal - Lucknow Pact - Surat split of congress / बंगाि का ववभाजि - िििऊ समझौता - सूरत कांग्रेस का ववभाजि b) Partition of Bengal - Surat split of congress - Lucknow Pact / बंगाि का ववभाजि - कांग्रेस का सूरत ववभाजि - िििऊ संधि c) Surat split of Congress - Partition of Bengal - Lucknow Pact / कांग्रेस का सूरत ववभाजि - बंगाि ववभाजि - िििऊ संधि d) Surat split ofA congressMAN - Lucknow SIR Pact W -I PartitionFIST ofUDY Bengal / कांग्रेस का सूरत ववभाजि - िििऊ समझौता - बंगाि का ववभाजि USEUSE CODE CODE “AMAN LI11V”E ONAMAN UNACADEMY ON& GET UNACADEMY 10% DISCOUNT AMAN SIR WIFISTUDY(OFFICIAL) Q1. With reference to the Indian freedom struggle, which one of the following is the correct chronological order of the given events? भारतीय वतंत्रता संग्राम